SFU Thesis Template Files

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Report of Debates (Hansard)

Fifh Session, 41st Parliament OFFICIAL REPORT OF DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday, February 18, 2020 Morning Sitting Issue No. 307 THE HONOURABLE DARRYL PLECAS, SPEAKER ISSN 1499-2175 PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Entered Confederation July 20, 1871) LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR Her Honour the Honourable Janet Austin, OBC Fifth Session, 41st Parliament SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Honourable Darryl Plecas EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Premier and President of the Executive Council ............................................................................................................... Hon. John Horgan Deputy Premier and Minister of Finance............................................................................................................................Hon. Carole James Minister of Advanced Education, Skills and Training..................................................................................................... Hon. Melanie Mark Minister of Agriculture.........................................................................................................................................................Hon. Lana Popham Attorney General.................................................................................................................................................................Hon. David Eby, QC Minister of Children and Family Development ............................................................................................................ Hon. Katrine Conroy Minister of State for Child Care......................................................................................................................................Hon. -

Daily Report November 21, 2019 Today in BC

BC Today – Daily Report November 21, 2019 Quotation of the day “I’m so glad that the minister is now in British Columbia where we can come and show him every day the community he represents and the people in this city and across the province are opposed to his pipeline.” Protestors including Peter McCartney, a climate campaigner with the Wilderness Committee, gave Vancouver Liberal MP Jonathan Wilkinson a taste of his new job as federal environment minister, showing up outside his constituency office while he was being sworn in Wednesday in Ottawa. Today in B.C. On the schedule The house will convene at 10 a.m. for question period. Wednesday’s debates and proceedings No new legislation was introduced on Wednesday. Attorney General David Eby tabled the Gaming Policy and Enforcement Branch’s annual report for 2018-19. The house completed committee stage on Bill 37, Financial Institutions Amendment Act, which, modernizes the regulatory framework for financial institutions operating in the province. The bill was immediately granted third reading. MLAs also completed committee stage on Bill 39, Miscellaneous Statutes (Minor Corrections) and Statute Revision Amendment Act. Bill 45, Taxation Standards Amendment Act, passed second reading unanimously. The bill adds a sin tax to vaping products and ups taxes on tobacco. MLAs in the chamber spent the rest of the afternoon at committee stage on Bill 40, Interpretation Amendment Act — the daylight savings time bill. Committee A continued committee stage on Bill 41, the UNDRIP legislation. At the legislature Attorney General David Eby introduced members of the ADR Institute of Canada to the house. -

BC Veterinarians Need Your Help Combined

Hello If you wish to help BC veterinarians address the shortage of veterinarians, you may wish to write your local MLA and ask them to support and increase to the number of BC students trained as veterinarians. Below is a sample email for you to send to your local MLA. You can also add to the email or replace it with your own. After the sample email, on page 2 and 3, is a list of all MLA email addresses to help you to find your MLA contact information. Should you wish to learn more about the shortage of veterinarians and the need for additional BC students to be trained as veterinarians, please scroll down to page 4 to read our summary document. Your help is greatly appreciated! Dear MLA, I wish to add my name to the list of British Columbians who find the shortage of veterinarians in BC unacceptable. We understand that BC can add an additional 20 BC student seats to BC’s regional veterinary college, but that the government declined to do so, citing costs. In the interest of animal health and welfare issues including relief from suffering and unnecessary death, public health, and biosecurity for BC, we ask you to ask the Minister of Advanced Education Anne Kang to fund an additional 20 BC seats at WCVM effective immediately. As a BC resident, I want my voice added as an individual who cares about the health and welfare of animals and who wishes the government to provide funding to help alleviate the shortage of veterinarians in BC. -

Report on the Budget 2012 Consultations

FIRST REPORT FOURTH SESSION THIRTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT Report on the Budget 2012 Consultations Select Standing Committee on Finance and Government Services NOVEMBER 2011 November 15, 2011 To the Honourable Legislative Assembly of the Province of British Columbia Honourable Members: I have the honour to present herewith the First Report of the Select Standing Committee on Finance and Government Services. The Report covers the work of the Committee in regard to the Budget 2012 public consultations. Respectfully submitted on behalf of the Committee, Rob Howard, MLA Chair Table of Contents Composition of the Committee ......................................................................................................................... i Terms of Reference ........................................................................................................................................... ii Letter from the Chair ...................................................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... v Budget 2012 Consultation Process ................................................................................................................... 1 Budget 2012 Consultation Paper .................................................................................................................. 1 Consultation Methods ................................................................................................................................. -

LIST of YOUR MLAS in the PROVINCE of BRITISH COLUMBIA As of April 2021

LIST OF YOUR MLAS IN THE PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA As of April 2021 NAME RIDING CAUCUS Bruce Banman Abbotsford South BC Liberal Party Michael de Jong, Q.C. Abbotsford West BC Liberal Party Pam Alexis Abbotsford-Mission BC NDP Roly Russell Boundary-Similkameen BC NDP Janet Routledge Burnaby North BC NDP Hon. Anne Kang Burnaby-Deer Lake BC NDP Hon. Raj Chouhan Burnaby-Edmonds BC NDP Hon. Katrina Chen Burnaby-Lougheed BC NDP Coralee Oakes Cariboo North BC Liberal Party Lorne Doerkson Cariboo-Chilcotin BC Liberal Party Dan Coulter Chilliwack BC NDP Kelli Paddon Chilliwack-Kent BC NDP Doug Clovechok Columbia River-Revelstoke BC Liberal Party Fin Donnelly Coquitlam-Burke Mountain BC NDP Hon. Selina Robinson Coquitlam-Maillardville BC NDP Ronna-Rae Leonard Courtenay-Comox BC NDP Sonia Furstenau Cowichan Valley BC Green Party Hon. Ravi Kahlon Delta North BC NDP Ian Paton Delta South BC Liberal Party G:\Hotlines\2021\2021-04-14_LIST OF YOUR MLAS IN THE PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA.docx Hon. Mitzi Dean Esquimalt-Metchosin BC NDP Jackie Tegart Fraser-Nicola BC Liberal Party Peter Milobar Kamloops-North Thompson BC Liberal Party Todd Stone Kamloops-South Thompson BC Liberal Party Ben Stewart Kelowna West BC Liberal Party Norm Letnick Kelowna-Lake Country BC Liberal Party Renee Merrifield Kelowna-Mission BC Liberal Party Tom Shypitka Kootenay East BC Liberal Party Hon. Katrine Conroy Kootenay West BC NDP Hon. John Horgan Langford-Juan de Fuca BC NDP Andrew Mercier Langley BC NDP Megan Dykeman Langley East BC NDP Bob D'Eith Maple Ridge-Mission BC NDP Hon. -

Official Report of Debates (Hansard)

First Session, 42nd Parliament OFFICIAL REPORT OF DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday, March 1, 2021 Afernoon Sitting Issue No. 16 THE HONOURABLE RAJ CHOUHAN, SPEAKER ISSN 1499-2175 PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Entered Confederation July 20, 1871) LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR Her Honour the Honourable Janet Austin, OBC First Session, 42nd Parliament SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Honourable Raj Chouhan EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Premier and President of the Executive Council ............................................................................................................... Hon. John Horgan Minister of Advanced Education and Skills Training...........................................................................................................Hon. Anne Kang Minister of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries......................................................................................................................Hon. Lana Popham Attorney General and Minister Responsible for Housing .............................................................................................Hon. David Eby, QC Minister of Children and Family Development ....................................................................................................................Hon. Mitzi Dean Minister of State for Child Care......................................................................................................................................Hon. Katrina Chen Minister of Citizens’ Services.....................................................................................................................................................Hon. -

Practical Steps

CHANGE WORKERS CHANGE for STUDENTS for CHANGE for THE ECONOMY CHANGE for OUR KIDS CHANGE BETTER CHANGE FAMILIES for the for PRACTICAL STEPS CHANGE for SENIORS CHANGE for the BETTER Authorized by Heather Harrison, Financial Agent, 604-430-8600 | CUPE 3787 WORKING TOGETHER TO ACHIEVE OUR HOPES AND DREAMS !e NDP platform is the result of intensive consultation with British Columbians by our party and the entire NDP caucus Dear friend, !e NDP platform is the result of intensive consultation with British Columbians by our party and the entire NDP caucus. You told us that you want a thoughtful, practical government that focuses on private sector jobs and growing our economy, lives within its means, and o"ers a hopeful vision of the future. !at’s what we have worked to achieve. First and foremost, our priority is to create opportunities for British Columbians to suc- ceed in a fast-changing and competitive economy. Our platform outlines the practical and a"ordable steps we can take to get us there – from expanding skills training, to reducing poverty and inequality, improving health care, pro- tecting our environment and #ghting climate change. !e changes we are proposing are designed to open up new opportunities for British Columbians to make the most of their own lives, and to build strong communities in a thriving, productive and green economy. As Leader of the BC NDP, I work with an outstanding team of British Columbians from all walks of life. I can promise you that we will work as hard as we can to provide you with a better government that listens, that cares, and that works with you to build a better, greener, more prosperous future for you and your family. -

Order in Council 212/2017

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ORDER OF THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL Order in Council No. 212 , Approved and Ordered !J'uliinant Governor Executive Council Chambers, Victoria On the recommendation of the undersigned, the Lieutenant Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, orders that (a) all previous designations of officials under section 9 (2) of the Constitution Act are rescinded, (b) the designations of officials in the Schedule to this order are made, (c) all previous appointments of parliamentary secretaries under section 12 of the Constitution Act are rescinded, and (d) the appointments of parliamentary secretaries in the Schedule to this order are made. (This part is for administrative purposes only and is not part of the Order.) Authority under which Order is made: Act and section: Constitution Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 66, ss. 9 (2) and 12 Other: 010142527 Page 1 of3 SCHEDULE 1 From among those persons appointed by the Lieutenant Governor to compose the Executive Council, the following persons are designated as officials with portfolio and the portfolio designated for each official is that shown opposite the name of the official: Honourable John Horgan Premier Honourable Melanie Mark Advanced Education, Skills and Training Honourable Lana Popham Agriculture Honourable David R. P. Eby Attorney General Honourable Katrine Conroy Children and Family Development Honourable Jinny Sims Citizens' Services Honourable Rob Fleming Education Honourable Michelle Mungall Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources -

[email protected]

Honorific First Name Last Name Riding Party email Mr Michael de Jong, Q.C Abbotsford West Liberal [email protected] Honourable Anne Kange Burnaby-Deer Lake NDP [email protected] Honourable Raj Chouhan Burnaby-Edmonds NDP [email protected] Dan Coulter Chilliwack NDP [email protected] Doug Clovechok Columbia River-Revelstoke Liberal [email protected] Honourable Mitzi Dean Esquimalt-Metchosin NDP [email protected] Peter Milobar Kamloops-North Thompson Liberal [email protected] Mike Bernier Peace River South Liberal [email protected] Honourable Nicholas Simons Powell River-Sunshine Coast NDP [email protected] Honourable Nathan Cullen Stikine NDP [email protected] Garry Begg Surrey-Guildford NDP [email protected] Honourable Harry Bains Surrey-Newton NDP [email protected] Honourable Bruce Ralston Q.C. Surrey-Whalley NDP [email protected] Honourable George Chow Vancouver-Fraserview NDP [email protected] Mr Bruce Banman Abbotsford South Liberal [email protected] Todd Stone Kamloops-South Thompson Liberal [email protected] Bob D'Eith Maple Ridge-Mission NDP [email protected] Jennifer Rice North Coast NDP [email protected] Henry Yao Richmond South Centre NDP [email protected] Trevor Halford Surrey-White Rock Liberal [email protected] Pam Alexis Abbotsford-Mission NDP [email protected] Roly Russell Boundary-Similkameen NDP [email protected] Coralee Oakes Cariboo -

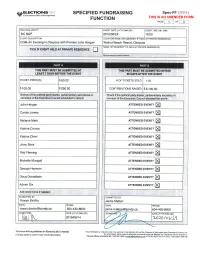

Specified Fundraising Function

~ 4ELECTIONS 3- SPECIFIED FUNDRAISING Spec-FF (17/1 1) • A non-partisan Office or the Legislature FUNCTION THIS IS AN AMENDED FORM PAGE ~ OF L 3 7 '-,. .. ~- " POLITICAL ENTITY EVENT DATE (YYYYIMM/DD) IEV ENT TIME (HH : MM) BC NOP 201 9/06/24 18:00 EVENT DESCRIPTION LOCATION NAME (OR ADDRESS' IF HELD AT PRIVATE RESIDENCE) C086-An Evening in Osoyoos with Premier John Horgan Walnut Beach Resort, Osoyoos NAME OF RESIDENT" (IF HELD AT PRIVATE RESIDENCE) TICK IF EVENT HELD AT PRIVATE RESIDENCE D . .. 'TJLI: ,. ·, .:.::11 ,.. 'J.el, C,! w ''.'.i -., ~.LI.•,.< • ;,J"j,- ',:• ~, ~ he •• 0'. ,c l - . "~- 'WII. ..'"""''"'""""' publle lntpl(llon. PART A PARTB THIS PART MUST BE SUBMITTED AT THIS PART MUST BE SUBMITTED WITHIN LEAST 7 DAYS BEFORE ifHE EVENT 60 DAYS AFTER THE EVENT e TICKET PRICE(S) $50.00 # OF TICKETS SOLD 110 $ 100.00 $ 250.00 CONTRIBUTIONS RAISED $ 9,100.00 Names of the political party leader, parliamentary secretaries or Check if the political party leader, parliamentary secretary or members of the Executive Council scheduled to attend: member of the Executive Council attended the event: John Horgan ATTENDED EVENT? 0 Carole James ATTENDED EVENT? 0 Melanie Mark ATTENDED EVENT? 0 Katrine Conroy ATTENDED EVENT? 0 Katrina Chen ATTENDED EVENT? 0 Jinny Sims ATTENDED EVENT? 0 Rob Fleming ATTENDED EVENT? 0 H Michelle Mungall ATTENDED EVENT? 0 George Heyman ATTENDED EVENT? 0 Doug Donaldson ATTENDED EVENT? 0 I; Adrian Dix ATTENDED EVENT? 0 ' ... ·:;~ -~ ,. , ' ., ., :,- Add more fonns if needed. ' SUBMITTED BY SUBMITTED BY Rowyn DeVito Jaime Matten EMAIL PHONE PHONE [email protected] 604-430-8600 cndp.ca 604-430-8600 DATE (YYYY/MM/DD) DATE (YYYY/MM/DD) 2019/06/1 4 '2.020 /01/2 q This form will bo published on Eloctlons BC's wobsito. -

Official Report of Debates (Hansard)

First Session, 42nd Parliament OFFICIAL REPORT OF DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday, April 12, 2021 Morning Sitting Issue No. 43 THE HONOURABLE RAJ CHOUHAN, SPEAKER ISSN 1499-2175 PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Entered Confederation July 20, 1871) LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR Her Honour the Honourable Janet Austin, OBC First Session, 42nd Parliament SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Honourable Raj Chouhan EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Premier and President of the Executive Council ............................................................................................................... Hon. John Horgan Minister of Advanced Education and Skills Training...........................................................................................................Hon. Anne Kang Minister of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries......................................................................................................................Hon. Lana Popham Attorney General and Minister Responsible for Housing .............................................................................................Hon. David Eby, QC Minister of Children and Family Development ....................................................................................................................Hon. Mitzi Dean Minister of State for Child Care......................................................................................................................................Hon. Katrina Chen Minister of Citizens’ Services.....................................................................................................................................................Hon. -

Debates of the Legislative Assembly (Hansard)

Fift h Session, 40th Parliament OFFICIAL REPORT OF DEBATES OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY (HANSARD) Tuesday, July 26, 2016 Morning Sitting Volume 40, Number 9 THE HONOURABLE LINDA REID, SPEAKER ISSN 0709-1281 (Print) ISSN 1499-2175 (Online) PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Entered Confederation July 20, 1871) LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR Her Honour the Honourable Judith Guichon, OBC Fifth Session, 40th Parliament SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Honourable Linda Reid EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Premier and President of the Executive Council ..............................................................................................................Hon. Christy Clark Deputy Premier and Minister of Natural Gas Development and Minister Responsible for Housing ......................Hon. Rich Coleman Minister of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation ......................................................................................................... Hon. John Rustad Minister of Advanced Education ............................................................................................................................... Hon. Andrew Wilkinson Minister of Agriculture ........................................................................................................................................................Hon. Norm Letnick Minister of Children and Family Development .......................................................................................................Hon. Stephanie Cadieux Minister of Community, Sport and Cultural Development