Chapter 8 Welfare Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of a National Lockdown in Response to COVID-19 Pandemic on the Prevalence of Clinical Symptoms in the Population

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.27.20076000; this version posted December 28, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC 4.0 International license . The effect of a national lockdown in response to COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of clinical symptoms in the population *1,2 *1,2 *1,2 *1,2,3 *1,2 1,2 Ayya Keshet , Amir Gavrieli , Hagai Rossman , Smadar Shilo , Tomer Meir , Tal Karady , Amit 1,2 1,2 1,2 1,2 1,2 4 4 Lavon , Dmitry Kolobkov , Iris Kalka , Saar Shoer , Anastasia Godneva , Ori Cohen, Adam Kariv , Ori Hoch , 4 4 5 5 2 6 4 Mushon Zer-Aviv , Noam Castel , Anat Ekka Zohar , Angela Irony , Benjamin Geiger , Yuval Dor , Dorit Hizi , 7 5, 8 1,2,☨ Ran Balicer , Varda Shalev , Eran Segal * Equal contribution 1 Department of Computer Science and Applied Mathematics, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel. 2 Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel. 3 Pediatric Diabetes Unit, Ruth Rappaport Children’s Hospital, Rambam Healthcare Campus, Haifa, Israel. 4 The public knowledge workshop, 26 Saadia Gaon st. Tel Aviv 5 Epidemiology and Database Research Unit, Maccabi Healthcare Services, Tel Aviv, Israel. 6 School of Medicine-IMRIC-Developmental Biology and Cancer Research, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. 7 Clalit Research Institute, Clalit Health Services, Tel Aviv, Israel. 8 School of Public Health, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. -

Arrested Development: the Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank

B’TSELEM - The Israeli Information Center for ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT Human Rights in the Occupied Territories 8 Hata’asiya St., Talpiot P.O. Box 53132 Jerusalem 91531 The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Tel. (972) 2-6735599 | Fax (972) 2-6749111 Barrier in the West Bank www.btselem.org | [email protected] October 2012 Arrested Development: The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank October 2012 Research and writing Eyal Hareuveni Editing Yael Stein Data coordination 'Abd al-Karim Sa'adi, Iyad Hadad, Atef Abu a-Rub, Salma a-Deb’i, ‘Amer ‘Aruri & Kareem Jubran Translation Deb Reich Processing geographical data Shai Efrati Cover Abandoned buildings near the barrier in the town of Bir Nabala, 24 September 2012. Photo Anne Paq, activestills.org B’Tselem would like to thank Jann Böddeling for his help in gathering material and analyzing the economic impact of the Separation Barrier; Nir Shalev and Alon Cohen- Lifshitz from Bimkom; Stefan Ziegler and Nicole Harari from UNRWA; and B’Tselem Reports Committee member Prof. Oren Yiftachel. ISBN 978-965-7613-00-9 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Part I The Barrier – A Temporary Security Measure? ................. 7 Part II Data ....................................................................... 13 Maps and Photographs ............................................................... 17 Part III The “Seam Zone” and the Permit Regime ..................... 25 Part IV Case Studies ............................................................ 43 Part V Violations of Palestinians’ Human Rights due to the Separation Barrier ..................................................... 63 Conclusions................................................................................ 69 Appendix A List of settlements, unauthorized outposts and industrial parks on the “Israeli” side of the Separation Barrier .................. 71 Appendix B Response from Israel's Ministry of Justice ....................... -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Israel Report

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Report Israel National | 1 Table of content: Israel National Report for Habitat III Forward 5-6 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 7-15 1. Managing rapid urbanization 7 2. Managing rural-urban linkages 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development 12 6. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 13 II. Land and Urban Planning: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 16-22 7. Ensuring sustainable urban planning and design 16 8. Improving urban land management, including addressing urban sprawl 17 9. Enhancing urban and peri-urban food production 18 10. Addressing urban mobility challenges 19 11. Improving technical capacity to plan and manage cities 20 Contributors to this report 12. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 21 • National Focal Point: Nethanel Lapidot, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry III. Environment and Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban of Construction and Housing Agenda 23-29 13. Climate status and policy 23 • National Coordinator: Hofit Wienreb Diamant, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry of Construction and Housing 14. Disaster risk reduction 24 • Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, Porter School for the Environment, Tel Aviv University 15. Minimizing Transportation Congestion 25 • Content Team: Ayelet Kraus, Ira Diamadi, Danya Vaknin, Yael Zilberstein, Ziv Rotem, Adva 16. Air Pollution 27 Livne, Noam Frank, Sagit Porat, Michal Shamay 17. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 28 • Reviewers: Dr. Yodan Rofe, Ben Gurion University; Dr. -

IDF Special Forces – Reservists – Conscientious Objectors – Peace Activists – State Protection

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: ISR35545 Country: Israel Date: 23 October 2009 Keywords: Israel – Netanya – Suicide bombings – IDF special forces – Reservists – Conscientious objectors – Peace activists – State protection This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on suicide bombs in 2000 to January 2002 in Netanya. 2. Deleted. 3. Please provide any information on recruitment of individuals to special army units for “chasing terrorists in neighbouring countries”, how often they would be called up, and repercussions for wanting to withdraw? 4. What evidence is there of repercussions from Israeli Jewish fanatics and Arabs or the military towards someone showing some pro-Palestinian sentiment (attending rallies, expressing sentiment, and helping Arabs get jobs)? Is there evidence there would be no state protection in the event of being harmed because of political opinions held? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on suicide bombs in 2000 to January 2002 in Netanya. According to a 2006 journal article published in GeoJournal there were no suicide attacks in Netanya during the period of 1994-2000. No reports of suicide bombings in 2000 in Netanya were found in a search of other available sources. -

Violations of Civil and Political Rights in the Realm of Planning and Building in Israel and the Occupied Territories

Violations of Civil and Political Rights in the Realm of Planning and Building in Israel and the Occupied Territories Shadow Report Submitted by Bimkom – Planners for Planning Rights Response to the State of Israel’s Report to the United Nations Regarding the Implementation of the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights September 2014 Written by Atty. Sharon Karni-Kohn Edited by Elana Silver and Ma'ayan Turner Contributions by Cesar Yeudkin, Nili Baruch, Sari Kronish, Nir Shalev, Alon Cohen Lifshitz Translated from Hebrew by Jessica Bonn 1 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….…5 Response to Pars. 44-48 in the State Report: Territorial Application of the Covenant………………………………………………………………………………5 Question 6a: Demolition of Illegal Construstions………………………………...5 Response to Pars. 57-59 in the State Report: House Demolition in the Bedouin Population…………………………………………………………………………....5 Response to Pars. 60-62 in the State Report: House Demolition in East Jerusalem…7 Question 6b: Planning in the Arab Localities…………………………………….8 Response to Pars. 64-77 in the State Report: Outline Plans in Arab Localities in Israel, Infrastructure and Industrial Zones…………………………………………………8 Response to Pars. 78-80 in the State Report: The Eastern Neighborhoods of Jerusalem……………………………………………………………………………10 Question 6c: State of the Unrecognized Bedouin Villages, Means for Halting House Demolitions and Proposed Law for Reaching an Arrangement for Bedouin Localities in the Negev, 2012…………………………………………...15 Response to Pars. 81-88 in the State Report: The Bedouin Population……….…15 Response to Pars. 89-93 in the State Report: Goldberg Commission…………….19 Response to Pars. 94-103 in the State Report: The Bedouin Population in the Negev – Government Decisions 3707 and 3708…………………………………………….19 Response to Par. -

HIVED M VUMRA^ W C Other Professional Fees

OMB NO. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust DepartmentoftheTn^sury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service 00 Note: The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. 2 6 For calendar year, 2006 , or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation mployer identification number Use the IRS TENSION ATTACH label. Otherwise , HE ADJMI-DWEK FAMILY FOUNDATION, INC. 13-3782816 print Number and shed (or P 0 box number if mail Is not delivered to street address) f mrs^^te g Telephone number ortype . 16TH 212-629_9600 /O ELI SERUYA, 500 SEVENTH AVENUE J V V V See Specific City or town , state, and ZIP code C If exemption applicationplacation .s pending, check hen: • O Instructions . ► EW YORK , NY 10 018 0 1 . Foreign organizations , check here Q 2. Foreign on,1za1dt1 mea p the e5% test,-.- ► ^ H Check typ e of or9anization X Section 501 (c)(3) exempt Private foundation here an attach computation -- . Q Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private fou ndati on status was te rminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method : Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here . (from Part 11, col. (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination Part 1, column (cq must be on cash basis.) ► $ 17 , 824 . ( under section 507 (b)( 1 6 , check here . -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

Israel - Wikipedia Page 1 of 97

Israel - Wikipedia Page 1 of 97 Coordinates: 31°N 35°E Israel :Arabic ; �י �� �� �אל :Israel (/ˈɪzriəl, ˈɪzreɪəl/; Hebrew formally known as the State of Israel Israel ,( � � ��ا �يل (Hebrew) לארשי Medinat Yisra'el), is a �מ ��י �נת �י �� �� �אל :Hebrew) country in Western Asia, located on the (Arabic) ليئارسإ southeastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea and the northern shore of the Red Sea. It has land borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the northeast, Jordan on the east, the Palestinian territories of the West Bank and Gaza Strip[20] to the east and west, respectively, and Egypt to the southwest. The country contains geographically diverse features within its relatively small Flag Emblem area.[21][22] Israel's economic and technological Anthem: "Hatikvah" (English: "The Hope") center is Tel Aviv,[23] while its seat of government and proclaimed capital is Jerusalem, although the state's sovereignty over Jerusalem has only partial recognition.[24][25][26][27][fn 4] Israel has evidence of the earliest migration of hominids out of Africa.[28] Canaanite tribes are archaeologically attested since the Middle Bronze Age,[29][30] while the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah emerged during the Iron Age.[31][32] The Neo-Assyrian Empire destroyed Israel around 720 BCE.[33] Judah was later conquered by the Babylonian, Persian and Hellenistic empires and had existed as Jewish autonomous provinces.[34][35] The successful Maccabean Revolt led to an independent Hasmonean kingdom by 110 BCE,[36] which in 63 BCE however became a client state of the Roman Republic that subsequently installed the Herodian dynasty in 37 BCE, and in 6 CE created the Roman province of Judea.[37] Judea lasted as a Roman province until the failed Jewish revolts resulted in widespread destruction,[36] the expulsion of the Jewish population[36][38] and the renaming of the region from Iudaea to Syria Palaestina.[39] Jewish presence in the region has persisted to a certain extent over the centuries. -

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Research and writing: Michal Belikoff and Safa Ali Agbaria Editing: Shirley Racah Steering committee: Samah Elkhatib-Ayoub, Ron Gerlitz, Azar Dakwar, Mohammed Khaliliye, Abed Kanaaneh, Jabir Asaqla, Ghaida Rinawie Zoabi, and Shirley Racah Critical review and assistance with research and writing: Ron Gerlitz and Shirley Racah Academic advisor: Dr. Nahum Ben-Elia Co-directors of Sikkuy’s Equality Policy Department: Abed Kanaaneh and Shirley Racah Project director for Injaz: Mohammed Khaliliye Hebrew language editing: Naomi Glick-Ozrad Production: Michal Belikoff English: IBRT Jerusalem Graphic design: Michal Schreiber Printed by: Defus Tira This pamphlet has also been published in Arabic and Hebrew and is available online at www.sikkuy.org.il and http://injaz.org.il Published with the generous assistance of: The European Union This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Sikkuy and Injaz and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The Moriah Fund UJA-Federation of New York The Jewish Federations of North America Social Venture Fund for Jewish-Arab Equality and Shared Society The Alan B. -

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

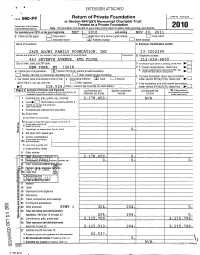

d I EXTENSION ATTACHED Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2010 Internal Revenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2010 , or tax year beginning DEC 1, 2010 and ending NOV 3 0, 2011 G Check all that apply. Initial return Initial return of a former public charity Ej Final return 0 Amended return ® Address chanae Name change Name of foundation A Employer identification number JACK ADJMI FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 13-3202295 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/swte B Telephone number 463 SEVENTH AVENUE , 4TH FLOOR 212-629-960 0 City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here NEW YORK , NY 10 018 D 1- Foreign organizations, check here 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation charitable Other taxable foundation Section 4947(a )( 1 ) nonexem pt trust 0 private E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, col. (c), line 16) = Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 111114 218 5 2 4 . (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507 b 1 B , check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b) (c), and (d) may not for charitable purposes necessarily equal the amounts in column (a)) expenses per books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received 2 , 178 , 450. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2005 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The o rganization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state re porting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year be and B Check If C Name of organization D Employer Identification number applicable Please use IRS change ta Qachange RICA IS RAEL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 13-1664048 E; a11gne ^ci See Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 0jretum specific 1 EAST 42ND STREET 1400 212-557-1600 Instruo retum uons City or town , state or country, and ZIP + 4 F nocounwro memos 0 Cash [X ,camel ded On° EW YORK , NY 10017 (sped ► [l^PP°ca"on pending • Section 501 (Il)c 3 organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates ? Yes OX No G Website : : / /AICF . WEBNET . ORG/ H(b) If 'Yes ,* enter number of affiliates' N/A J Organization type (deckonIyone) ► [ 501(c) ( 3 ) I (insert no ) ] 4947(a)(1) or L] 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included ? N/A Yes E__1 No Is(ITthis , attach a list) K Check here Q the organization' s gross receipts are normally not The 110- if more than $25 ,000 .