Evolution of Mating Behaviour in Honeybees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sperm Use During Egg Fertilization in the Honeybee (Apis Mellifera) Maria Rubinsky SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2010 Sperm Use During Egg Fertilization in the Honeybee (Apis Mellifera) Maria Rubinsky SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Rubinsky, Maria, "Sperm Use During Egg Fertilization in the Honeybee (Apis Mellifera)" (2010). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 914. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/914 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sperm use during egg fertilization in the honeybee (Apis mellifera) Maria Rubinsky November, 2010 Supervisors: Susanne Den Boer, Boris Baer, CIBER; The University of Western Australia Perth, Western Australia Academic Director: Tony Cummings Home Institution: Brown University Major: Human Biology- Evolution, Ecosystems, and Environment Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Australia: Rainforest, Reef, and Cultural Ecology, SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2010 Abstract A technique to quantify sperm use in honeybee queens (Apis mellifera) was developed and used to analyze the number of sperm used in different groups of honeybee queens. To do this a queen was placed on a frame with worker cells containing no eggs, and an excluder box was placed around her. The frame was put back into the colony and removed after two and a half hours. -

Analysis of Honeybee Drone Activity During the Mating Season in Northwestern Argentina

insects Article Analysis of Honeybee Drone Activity during the Mating Season in Northwestern Argentina Maria Marta Ayup 1,2,3 , Philipp Gärtner 3, José L. Agosto-Rivera 4, Peter Marendy 5,6 , Paulo de Souza 5,7 and Alberto Galindo-Cardona 1,8,* 1 National Scientific and Technical Research Council, CONICET, CCT, Tucumán 4000, Argentina; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Natural Sciences, National University of Tucumán (UNT), Tucumán 4000, Argentina 3 IER (Regional Ecology Institute), CONICET, Tucumán 4000, Argentina; [email protected] 4 Rio Piedras Campus, University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras 00927, Puerto Rico; [email protected] 5 Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, CSIRO, Canberra 2601, Australia; [email protected] (P.M.); paulo.desouza@griffith.edu.au (P.d.S.) 6 School of Technology, Environments and Design, University of Tasmania, Tasmania 7000, Australia 7 School of Information and Communication Technology, Griffith University, Nathan 4111, Australia 8 Miguel Lillo Foundation, Tucumán 4000, Argentina * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +54-0381-640-8826 Simple Summary: When we think of social insects, we mostly neglect males and their biology. Honeybee males or drones are an example. Like queens, drones are founders of the colony, but unlike queens and workers, their activity is not well-known. Drones exit the hive to mate as their only goal, in spite of the high chances of getting lost, being preyed upon and starving; and only if they are lucky, they will die when mating. These nuptial flights take place in Drone Congregation Areas during Citation: Ayup, M.M.; Gärtner, P.; spring and summer, and we know that their exit time is in the afternoons. -

The Coexistence

Myrmecological News 13 37-55 2009, Online Earlier Natural history and phylogeny of the fungus-farming ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini) Natasha J. MEHDIABADI & Ted R. SCHULTZ Abstract Ants of the tribe Attini comprise a monophyletic group of approximately 230 described and many more undescribed species that obligately depend on the cultivation of fungus for food. In return, the ants nourish, protect, and disperse their fungal cultivars. Although all members of this tribe cultivate fungi, attine ants are surprisingly heterogeneous with regard to symbiont associations and agricultural system, colony size and social structure, nesting behavior, and mating system. This variation is a key reason that the Attini have become a model system for understanding the evolution of complex symbioses. Here, we review the natural-history traits of fungus-growing ants in the context of a recently published phylo- geny, collating patterns of evolution and symbiotic coadaptation in a variety of colony and fungus-gardening traits in a number of major lineages. We discuss the implications of these patterns and suggest future research directions. Key words: Hymenoptera, Formicidae, fungus-growing ants, leafcutter ants, colony life, natural history, evolution, mating, agriculture, review. Myrmecol. News 13: 37-55 (online xxx 2008) ISSN 1994-4136 (print), ISSN 1997-3500 (online) Received 12 June 2009; revision received 24 September 2009; accepted 28 September 2009 Dr. Natasha J. Mehdiabadi* (contact author) & Dr. Ted R. Schultz* (contact author), Department of Entomology and Laboratories of Analytical Biology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, NHB, CE518, MRC 188, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] * Both authors contributed equally to the work. -

Observation of the Mating Behavior of Honey

Insects 2014, 5, 513-527; doi:10.3390/insects5030513 OPEN ACCESS insects ISSN 2075-4450 www.mdpi.com/journal/insects/ Article Observation of the Mating Behavior of Honey Bee (Apis mellifera L.) Queens Using Radio-Frequency Identification (RFID): Factors Influencing the Duration and Frequency of Nuptial Flights Ina Monika Margret Heidinger 1,2,*, Marina Doris Meixner 1, Stefan Berg 2 and Ralph Büchler 1 1 LLH, Bee Institute, Erlenstrasse 9, D-35274 Kirchhain, Germany; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.D.M.); [email protected] (R.B.) 2 Bavarian State Institute for Viticulture and Horticulture, Bee Research Center, An der Steige 15, D-97206 Veitshöchheim, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-931-9801-320; Fax: +49-931-9801-350. Received: 17 December 2013; in revised form: 16 April 2014 / Accepted: 20 June 2014 / Published: 1 July 2014 Abstract: We used radio-frequency identification (RFID) to record the duration and frequency of nuptial flights of honey bee queens (Apis mellifera carnica) at two mainland mating apiaries. We investigated the effect of a number of factors on flight duration and frequency: mating apiary, number of drone colonies, queen’s age and temperature. We found significant differences between the two locations concerning the number of flights on the first three days. We also observed an effect of the ambient temperature, with queens flying less often but longer at high temperatures compared to lower temperatures. Increasing the number of drone colonies from 33 to 80 colonies had no effect on the duration or on the frequency of nuptial flights. -

Lipid and Energy Contents in the Bodies of Queens of Atta Sexdens Rubropilosa Forel (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): Pre-And Post-Nuptial Flight

Lipid and energy contents in the bodies of queens of Atta sexdens rubropilosa Forel (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): pre-and post-nuptial flight Ricardo Toshio Fujihara1, Roberto da Silva Camargo1 & Luiz Carlos Forti1 1Laboratório de Insetos Sociais-Praga, Departamento de Produção Vegetal, Faculdade de Ciências Agronômicas, Universidade Estadual Paulista P.O. Box 237, 18610–307 Botucatu-SP, Brazil. [email protected], [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT. Lipid and energy contents in the bodies of queens of Atta sexdens rubropilosa Forel (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): pre- and post-nuptial flight. The nuptial flight allows males and females to meet and copulate and both need energy to perform this activity. Before leaving the nest, males and females are well nourished and ready to mate. However, little is known about the lipid and energy contents in females before the nuptial flight (virgins) and after it (mated females). In this work we measured lipid concentrations in relation to body weight in these individuals. Our results showed that 16.82% of the bodies of young virgin females one month before mating flight are composed of lipids, contrasting with the 32.62% lipid content in mated females who had not excavated their nest yet, and 32.88% in those who had. The energy content measured for virgin females was 2942.63 J, contrasting with 6110.01 J for queens before excavating the nest and 5677.51 J after excavation. Based on our results, we conclude that the body mass, and therefore the lipid and energy contents in the bodies of Atta sexdens rubropilosa queens double during the last month before the nuptial flight. -

Wildlife Trade Operation Proposal - Queen Ant Harvesting

Wildlife Trade Operation Proposal - Queen Ant Harvesting 1. Title and Introduction 1.1/1.2 Scientific and Common Names Please refer to Attachment A, outlining the ant species subject to harvest, giving both scientific and common names where applicable (some species are only referred to by their scientific name) and the proposed annual harvest quota which will not be exceeded. 1.3 Location of harvest Harvest will be conducted on two privately owned properties in McCrae Victoria, and one privately owned property at Forrest Lake in Queensland. 1.4 Description of what is being harvested Please refer to Attachment A for an outline of the species to be harvested. The harvest is of live, newly mated, adult queen ants. 1.5 Is the species protected under State or Federal legislation Ants are non-listed invertebrates and are as such unprotected under Victorian or Queensland State Legislation. Under Federal legislation the only protection to these species relates to the export of native wildlife, which this application seeks to satisfy. No species listed under the EPBC Act as threatened (excluding the conservation dependent category) or listed as endangered, vulnerable or least concern under Victorian or Queensland legislation will be harvested. 2. Statement of general goal/aims The applicant began collecting queen ants and watching them build colonies as a personal hobby, during which time he has identified strong interest from international collectors in acquiring species of ants found in Australia. The goal of this application is to seek approval for a WTO to export queen ants. The ability to export queen ants will also increase the export sales of specialized ant keeping equipment, manufactured in Australia, to overseas ant keepers. -

Biology & Anatomy of the Honey

International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe) African Insect Science for Food and Health Dr. Segenet Kelemu, Director General Major Programme Areas • COMMERCIAL INSECTS • MALARIA • BEE HEALTH • SLEEPING • BIOPROSPECTING SICKNESS • BIODIVERSITY • ARBOVIRAL CONSERVATION INFECTIONS • CLIMATE CHANGE Environmental Human Health Health • HORTICULTURAL Plant Health Animal Health CROP PESTS • STAPLE FOOD CROP • TSETSE PESTS • TICKS • PLANTATION CROP PESTS CONTINENTAL TRAINING OF TRAINERS (TOTs) ON BEE DISEASES AND PESTS, PREVENTION AND CONTROL March 31 – April 4 2014 Honeybee biology and queen breeding Suresh Raina, icipe THE TAXONOMY AND IDENTIFICATION OF BEES Bees all belong to: Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Arthropoda Class: Insecta Order: Hymenoptera Superfamily: Apoidea • The Apoidea comprises two groups, the Anthophila (bees) and the Spheciformes (sphecid wasps). • The Anthophila has six families in the Afrotropical Region: Colletidae, Andrenidae, Halictidae, Melittidae, Megachilidae and Apidae. Subfamilies Apinae, Nomadinae and Xylocopinae Apidae The Apidae comprising the common honey bees, stingless bees, carpenter bees, orchid bees, cuckoo bees, bumblebees, and various other tribes and groups. Many are valuable pollinators in natural habitats and for agricultural crops. Apidae has three Subfamilies 1. Apinae: honey bees, bumblebees, stingless bees, orchid bees, digger bees, and 14 other tribes, the majority of which are solitary and whose nests are simple burrows in the soil. However, honey bees, stingless bees, and bumblebees are eusocial or colonial.. Subfamily Nomadinae 2. Nomadinae The subfamily Nomadinae, or cuckoo bees, has 31 genera in 10 tribes which are all cleptoparasites bees for their habit of invading nests of solitary bees and laying their own eggs Thyreus splendidulus Democratic Republic of Congo. Image: Nicolas Vereecken (Free University of Brussels) Subfamily Xylocopinae 3. -

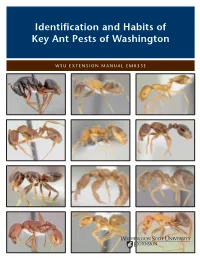

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington WSU EXTENSION MANUAL EM033E Cover images are from www.antweb.org, as photographed by April Nobile. Top row (left to right): Carpenter ant, Camponotus modoc; Velvety tree ant, Liometopum occidentale; Pharaoh ant, Monomorium pharaonis. Second row (left to right): Aphaenogaster spp.; Thief ant, Solenopsis molesta; Pavement ant, Tetramorium spp. Third row (left to right): Odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile; Ponerine ant, Hypoponera punctatissima; False honey ant, Prenolepis imparis. Bottom row (left to right): Harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex spp.; Moisture ant, Lasius pallitarsis; Thatching ant, Formica rufa. By Laurel Hansen, adjunct entomologist, Washington State University, Department of Entomology; and Art Antonelli, emeritus entomologist, WSU Extension. Originally written in 1976 by Roger Akre (deceased), WSU entomologist; and Art Antonelli. Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) are an easily anywhere from several hundred to millions of recognized group of social insects. The workers individuals. Among the largest ant colonies are are wingless, have elbowed antennae, and have a the army ants of the American tropics, with up petiole (narrow constriction) of one or two segments to several million workers, and the driver ants of between the mesosoma (middle section) and the Africa, with 30 million to 40 million workers. A gaster (last section) (Fig. 1). thatching ant (Formica) colony in Japan covering many acres was estimated to have 348 million Ants are one of the most common and abundant workers. However, most ant colonies probably fall insects. A 1990 count revealed 8,800 species of ants within the range of 300 to 50,000 individuals. -

A Community of Ants, Fungi, and Bacteria

28 Jul 2001 17:20 AR AR135-14.tex AR135-14.sgm ARv2(2001/05/10) P1: GPQ Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001. 55:357–80 Copyright c 2001 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved ACOMMUNITY OF ANTS,FUNGI, AND BACTERIA: A Multilateral Approach to Studying Symbiosis Cameron R. Currie Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, 2041 Haworth Hall, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045-7534; e-mail: [email protected] Key Words actinomycetes, antibiotics, coevolution, fungus-growing ants, mutualism ■ Abstract The ancient and highly evolved mutualism between fungus-growing ants and their fungi is a textbook example of symbiosis. The ants carefully tend the fungus, which serves as their main food source, and traditionally are believed to be so successful at fungal cultivation that they are able to maintain the fungus free of microbial pathogens. This assumption is surprising in light of theories on the evolution of parasitism, especially for those species of ants that have been clonally propagating their cultivars for millions of years. Recent work has established that, as theoretically predicted, the gardens of fungus-growing ants are host to a specialized, virulent, and highly evolved fungal pathogen in the genus Escovopsis. In addition, the ants have evolved a mutualistic association with filamentous bacteria (actinomycetes) that pro- duce antibiotics that suppress the growth of Escovopsis. Thus, the attine symbiosis appears to be a coevolutionary “arms race” between the garden parasite Escovopsis on the one hand and the ant-fungus-actinomycete tripartite mutualism on the other. These recent findings indicate that microbes may be key components in the regulation of other symbiotic associations between higher organisms. -

Novel Fungal Disease in Complex Leaf-Cutting Ant Societies

Ecological Entomology (2009), 34, 214–220 Novel fungal disease in complex leaf-cutting ant societies DAVID P. HUGHES 1,2 , HARRY C. EVANS 3 , NIGEL HYWEL-JONES 4,5 , JACOBUS J. BOOMSMA 1,2 and SOPHIE A. O. ARMITAGE 1,2 1 Department of Biology, Centre for Social Evolution, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark , 2 Department of Organismal, Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, U.S.A. School of Bioscience, University of Exeter, Exeter, U.K. 3 CAB International, U.K. Centre, Silwood Park, Ascot, Berkshire, U.K. , 4 Mycology Laboratory, National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, Science Park, Pathum Thani, Thailand and 5 Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität, Münster, Germany Abstract . 1. The leaf-cutting ants practise an advanced system of mycophagy where they grow a fungus as a food source. As a consequence of parasite threats to their crops, they have evolved a system of morphological, behavioural, and chemical defences, particularly against fungal pathogens (mycopathogens). 2. Specific fungal diseases of the leaf-cutting ants themselves have not been described, possibly because broad spectrum anti-fungal defences against mycopathogens have reduced their susceptibility to entomopathogens. 3. Using morphological and molecular tools, the present study documents three rare infection events of Acromyrmex and Atta leaf-cutting ants by Ophiocordyceps fungi, a genus of entomopathogens that is normally highly specific in its host choice. 4. As leaf-cutting ants have been intensively studied, the absence of prior records of Ophiocordyceps suggests that these infections may be a novel event and that switching from one host to another is possible. -

Carpenter Ants

E-412 12-11 Carpenter Ants Wizzie Brown and Roger E. Gold* arpenter ants, Camponotus sp., are social reproductives (kings C insects that make their colonies primarily and queens). Each in wood. They hollow out wood or excavate colony has only one insulation to build their nests. Unlike termites, they functional queen, do not eat wood. except in mature Outdoors, carpenter ants are not serious pests. colonies during the Although their excavations may occasionally weaken Figure 1. Adult carpenter ant. swarming season. tree branches and limbs, in most cases, carpenter ants Carpenter ants nest in wood that is already rotten or damaged by can be yellowish red, solid black, or a combination termites. of black, red, and reddish orange. Unlike other ants, They become pests when they nest or forage for they have only one segment (or node) between the food in homes and other buildings. An infestation thorax and abdomen, a circle of hairs at the tip of the usually begins when part of an existing colony moves abdomen, and an evenly rounded thorax (no spines or into a house. bumps) when viewed from the side. The presence of carpenter ants can indicate that Winged carpenter ants resemble winged termites a building has problems such as moisture, rotting and, in Texas, it is not uncommon for both of these wood, or other conditions conducive to infestations. wood-destroying insects to swarm at the same time. Texas species of carpenter ants cause less damage to It is vital that they be identified accurately, because structural wood than do carpenter ants from other control measures differ greatly between the two insect parts of the United States. -

Social Parasites of Ant Colonies

Social parasites of ant colonies How social parasites can thrive in ant nests and the consequences for their hosts. M. G. Weites Student number: S2127067 July 2014 Supervisor: R. van Klink, PhD Bachelor thesis Biology University of Groningen Summary Parasitism affect a wide range of organisms and the interactions between the host and the parasite can lead to an evolutionary arms race. Parasitism comes in different forms and one of them is social parasitism. In social parasitism, an organism parasitises on the relationship between members of the host species. Ant colonies are home to numerous social parasites that take advantage of how ant workers take care of the queen and her brood. In this thesis we will focus on socially parasitic ants and butterflies. Their ecology and the different ways and mimicries used to be accepted into the colony of their host, are observed. Also the evolution of these parasitic life styles and possible evolutionary arms race are discussed and recent data is used to support the claims that are made. Parasitic ants can be divided into different groups: species that feed on ant regurgitations (xenobionts), species that kill queen and take over a colony (temporary parasites), slave- makers and species that do not have workers and who’s brood is cared for in a host colony (inquilines). The evolutionary pathways to these groups are complex and the exact way of evolution remains unsolved. The evolution of parasitic butterflies seems to be somewhat clearer: mutualistic species gave rise to predatory species which in turn gave give to cuckoo species. There was evidence for an evolutionary arms race between parasitic ants and their host but no evidence has been for one between parasitic butterflies and their host ants.