"Oracles": 2010 (.Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

Newsletter 22/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 22/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 193 - Oktober 2006 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 22/06 (Nr. 193) Oktober 2006 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, diesem Sinne sind wir guten Mutes, unse- liebe Filmfreunde! ren Festivalbericht in einem der kommen- Kennen Sie das auch? Da macht man be- den Newsletter nachzureichen. reits während der Fertigstellung des einen Newsletters große Pläne für den darauf Aber jetzt zu einem viel wichtigeren The- folgenden nächsten Newsletter und prompt ma. Denn wer von uns in den vergangenen wird einem ein Strich durch die Rechnung Wochen bereits die limitierte Steelbook- gemacht. So in unserem Fall. Der für die Edition der SCANNERS-Trilogie erwor- jetzt vorliegende Ausgabe 193 vorgesehene ben hat, der darf seinen ursprünglichen Bericht über das Karlsruher Todd-AO- Ärger über Teil 2 der Trilogie rasch ver- Festival musste kurzerhand wieder auf Eis gessen. Hersteller Black Hill ließ Folgen- gelegt werden. Und dafür gibt es viele gute des verlautbaren: Gründe. Da ist zunächst das Platzproblem. Im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes ”platzt” der ”Käufer der Verleih-Fassung der Scanners neue Newsletter wieder aus allen Nähten. Box haben sicherlich bemerkt, dass der Wenn Sie also bislang zu jenen Unglückli- 59 prall gefüllte Seiten - und das nur mit zweite Teil um circa 100 Sekunden gekürzt chen gehören, die SCANNERS 2 nur in anstehenden amerikanischen Releases! Des ist. -

FOR SALE ‐ GENESIS BOX SETS These Are All the Rhino Sets Distributed to the USA Through Amazon

FOR SALE ‐ GENESIS BOX SETS These are all the Rhino sets distributed to the USA through Amazon. All are in excellent condition. Each individual album includes the CD(s) and a DVD with the 5.1 files in NTSC/DVD‐Audio/DTS/Dolby Digital (except The Movie Box). DVDs also include some video extras. Artist Title Notes Price Genesis Green Box, 1970‐1975 Trespass; Nursery Cryme; Foxtrot; Selling $ 300.00 England By The Pound; The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway; Genesis 1970‐1975 Extras Genesis Blue Box, 1976‐1982 A Trick of the Tail; Wind & Wuthering; …and $ 300.00 then there were three; Duke; ababab; Genesis 1976‐1982 Extras Genesis Red Box, 1983‐1998 Genesis; Invisible Touch; We Can’t Dance; $ 200.00 …Calling All Stations; Genesis 1983‐1998 Extras Genesis Black Box, 1973‐2007 LIVE Live; Seconds Out; Three Sides Live; The Way $ 225.00 We Walk; Live Over Europe (2 CDs only, slot provided for this album which was not included as part of this set); Genesis Live 1973‐2007 Extras Genesis White Box, 1981‐2007 The Movie Box Three Sides Live (1 DVD); The Mama Tour (1 $ 80.00 DVD); Live at Wembley Stadium (1 DVD); The Way We Walk Live in Concert (1 DVD); The Movie Box 1981‐2007 Extras FOR SALE ‐ SACD STEREO Artist Title Notes Price PENDING SALE ‐ Boston Boston $ 12.00 Chicago Symphony/Dvorak New World Symphony $ 7.00 Dylan, Bob The Free Wheelin' Bob Dylan $ 12.00 Dylan, Bob Highway 61 revisited $ 10.00 Guaraldi Trio, Vince A Charlie Brown Christmas SACD Only $ 12.00 PENDING SALE ‐ Journey Escape SACD Only $ 12.00 The Police Synchronicity SACD Only $ 15.00 -

Personality and Dvds

personality FOLIOS and DVDs 6 PERSONALITY FOLIOS & DVDS Alfred’s Classic Album Editions Songbooks of the legendary recordings that defined and shaped rock and roll! Alfred’s Classic Album Editions Alfred’s Eagles Desperado Led Zeppelin I Titles: Bitter Creek • Certain Kind of Fool • Chug All Night • Desperado • Desperado Part II Titles: Good Times Bad Times • Babe I’m Gonna Leave You • You Shook Me • Dazed and • Doolin-Dalton • Doolin-Dalton Part II • Earlybird • Most of Us Are Sad • Nightingale • Out of Confused • Your Time Is Gonna Come • Black Mountain Side • Communication Breakdown Control • Outlaw Man • Peaceful Easy Feeling • Saturday Night • Take It Easy • Take the Devil • I Can’t Quit You Baby • How Many More Times. • Tequila Sunrise • Train Leaves Here This Mornin’ • Tryin’ Twenty One • Witchy Woman. Authentic Guitar TAB..............$22.95 00-GF0417A____ Piano/Vocal/Chords ...............$16.95 00-25945____ UPC: 038081305882 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4697-5 UPC: 038081281810 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4258-8 Authentic Bass TAB.................$16.95 00-28266____ UPC: 038081308333 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4818-4 Hotel California Titles: Hotel California • New Kid in Town • Life in the Fast Lane • Wasted Time • Wasted Time Led Zeppelin II (Reprise) • Victim of Love • Pretty Maids All in a Row • Try and Love Again • Last Resort. Titles: Whole Lotta Love • What Is and What Should Never Be • The Lemon Song • Thank Authentic Guitar TAB..............$19.95 00-24550____ You • Heartbreaker • Living Loving Maid (She’s Just a Woman) • Ramble On • Moby Dick UPC: 038081270067 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-3919-9 • Bring It on Home. -

Jazz in the Pacific Northwest Lynn Darroch

Advance Praise “Lynn Darroch has put together a great resource for musicians, listeners, and history buffs, compiling what seems to be the most comprehensive resource about the history of jazz in the Northwest. This book will do the important job of keeping the memories and stories alive of musicians and venues that, while they may be immortalized through recordings, have important history that may otherwise be lost to the murkiness of time. Darroch has done the community and the music a great service by dedicating himself to telling these stories.” —John Nastos “Lynn Darroch illuminates the rich history of jazz in the Pacific Northwest from the early twentieth century to the present. Interweaving factors of culture, economics, politics, landscape, and weather, he helps us to understand how the Northwest grew so many fine jazz artists and why the region continues to attract musicians from New Orleans, New York, California, Europe, and South America. He concentrates on the traditions of the big port cities, Seattle and Portland, and underlines the importance of musicians from places like Wenatchee, Spokane, Eugene, and Bend. Darroch has the curiosity of a journalist, the investigative skills of a historian and the language of a poet. His writing about music makes you want to hear it.” —Doug Ramsey “With the skills of a curator, Lynn Darroch brings us the inspiring history and personal stories of Northwest jazz musicians whose need for home, love of landscape, and desire to express, all culminate into the unique makeup of jazz in Portland and Seattle. Thank you Lynn for a great read and its contribution to jazz. -

March 2021 BLUESLETTER Washington Blues Society in This Issue

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT WASHINGTON BLUES SOCIETY Hi Blues Fans! Proud Recipient of a 2009 I just finished watching our Keeping the Blues Alive Award 2021 Musicians Relief Fund/ HART Fundraiser and I must 2021 OFFICERS say I thought it was great. I am President, Tony Frederickson [email protected]@wablues.org so grateful for the generous Vice President, Rick Bowen [email protected]@wablues.org donation of the musical talents Secretary, Marisue Thomas [email protected]@wablues.org of John Nemeth & the Blues Treasurer, Ray Kurth [email protected]@wablues.org Dreamers, Theresa James, Terry Editor, Eric Steiner [email protected]@wablues.org Wilson & the Rhythm Tramps and Too Slim & the Taildraggers! 2021 DIRECTORS It was a good show and well worth reviewing again and again if Music Director, Open [email protected]@wablues.org you missed it! Also, a big shout out to Rick Bowen and Jeff Menteer Membership, Chad Creamer [email protected]@wablues.org for their talents for the production of this event. I also want to say Education, Open [email protected]@wablues.org “Thank You” to all of you who made donations! If you are looking Volunteers, Rhea Rolfe [email protected]@wablues.org for a little music to fill some time this would be a great three-hour Merchandise, Tony Frederickson [email protected]@wablues.org window and any donations you might be able to make would be very Advertising, Open [email protected]@wablues.org much appreciated. If you are interested go to our new YouTube page (Washington Blues Society) and check it out. -

FEATURING the COASTERS Director’S Circle

FEATURING THE COASTERS Director’s Circle Dr. David & Katherine Arnold Bill & Linda Bayless Russell & Joan Bennett Van & Melissa Billingsley Neal & Joanne Cadieu Dr. Al & Pat Covington Wade & Beth Dunbar Ellerbe Pharmacy Joe & Diana Everett Brian & Danielle Goodman Representative Ken & Cindy Goodman Lee & Terry Howell G.R. & Mary Ellen Kindley J.C. & Hilda Lamm Terry & Cheryl Lewis David & Kim Lindsey Duane & Carol Linker Lazelle & Judy Marks Lonnie & Cheryl McCaskill Dr. Dale & Thomasa McInnis Tom & Janice McInnis Social Media Senator Gene & Donna McLaurin Are You Connected to the Cole? Dean & Candy Nichols Jerry & Brenda Purcell Ken & Claudia Robinette Stay in touch with the latest news from the Cole Auditorium. Nicholas & Lucy Sojka Dr. John & Sue Stevenson Thad & Mary Jane Ussery Lee & Tanya Wallace www.facebook.com/coleaud www.twitter.com/coleaud Larry & Michele Weatherly Facebook and Twitter feeds are available to patrons Thank you Director’s Circle Members! without having to register with the services. Just type the web addresses above directly into your Internet Now in it’s fifth year, the Director’s Circle helps Richmond browser’s address bar access to the information posted. Community College raise local funds critical to the success of the Cole Auditorium, RCC, and most importantly, our students. Season Ticket holders interested in joining the Director’s Circle should contact Joey Bennett at (910) 410-1691 or RCC Foundation COLE-MAIL Executive Director Olivia Webb at (910) 410-1807. www.richmondcc.edu www.richmondcc.edu ~Browse -

Songwriters-In-The-Round: Vicki Peterson, Shelly Peiken, Bleu, Roy

Cal Poly Pomona Music Department 3801 W. Temple Avenue, Pomona, CA 91768 Phone: 909-869-3554 Fax: 909-869-4145 Website: http://www.cpp.edu/~class/music/ For Details, Contact: Teresa Kelly, Music Department Publicist Email: [email protected] For Release: January 25, 2016 Phone: 909-869-3554 Songwriters-in-the-Round: Vicki Peterson, Shelly Peiken, Bleu, Roy Zimmerman, Eleni Mandell, Kelly Jones, Tim Cohan, Linus of Hollywood, Arthur Winer, MC Prototype & Jess Furman in concert Wednesday, February 24th, 8:00 PM in the Cal Poly Pomona Music Recital Hall. Tickets are $15 general/$10 student, available at http://csupomona.tix.com/Event.aspx?EventCode=840454 or through the Publicity Office, 24-188, (909) 869-3554. The Songwriters-in-the-Round concert will be preceded by: 3rd Songwriting Summit • Wednesday, February 24th, 2:00-5:00 PM in the Cal Poly Pomona Music Recital Hall, 24-191. Master classes are FREE and open to the public. For more information, please contact Prof. Arthur Winer at [email protected]. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SPECIAL EVENT: Songwriters-in-the-Round: Vicki Peterson, Shelly Peiken, Bleu, Roy Zimmerman, Eleni Mandell, Kelly Jones, Tim Cohan, Linus of Hollywood, Arthur Winer, MC Prototype & Jess Furman in concert The Cal Poly Pomona Music Department and the Songwriter Showcase ensemble are pleased to announce an unusual and diverse group of acclaimed songwriters together in concert for an evening of Songwriters-in-the-Round Wednesday, February 24th, 8:00 PM. Featuring songwriters Vicki Peterson (The Bangles), Shelly Peiken ("What a Girl Wants"), Bleu, Roy Zimmerman, Eleni Mandell (The Living Sisters), Kelly Jones, Tim Cohan (Tryst, MacArthur), Linus of Hollywood, Arthur Winer (MacArthur), MC Prototype & Jess Furman sharing the stage for a night of original music. -

Heart Alive in Seattle Mp3, Flac, Wma

Heart Alive In Seattle mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Alive In Seattle Country: Europe Released: 2003 Style: Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1417 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1360 mb WMA version RAR size: 1795 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 518 Other Formats: APE MP4 MPC ADX XM AIFF MIDI Tracklist 1 Crazy On You 2 Sister Wild Rose 3 The Witch 4 Straight On 5 These Dreams 6 Mistral Wind 7 Alone 8 Dog And Butterfly 9 Mona Lisa And Mad Hatters 10 Battle Of Evermore 11 Heaven 12 Magic Man 13 Two Faces Of Eve 14 Love Alive 15 Break The Rock 16 Barracuda 17 Wild Child 18 Black Dog 19 Dreamboat Annie Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Heart Amalgamated Copyright (c) – Image Entertainment Credits Bass Guitar – Mike Inez Drums, Percussion – Ben Smith Guitar, Acoustic Guitar, Lap Steel Guitar, Backing Vocals – Scott Olson Guitar, Acoustic Guitar, Vocals, Mandolin, Ukulele – Nancy Wilson Keyboards – Tom Kellock Vocals, Acoustic Guitar, Autoharp, Flute, Ukulele – Ann Wilson Notes Program Content and Artwork: (C) 2002 Heart Amalgamated. DVD Package Design: (c) MMIII Image Entertainment, Inc. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 8 28765 10749 5 Label Code: LC00116 Rights Society: BIEM/GEMA Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year EPC 517327 2, Alive In Seattle EPC 517327 2, Heart Epic, Legacy Europe 2003 5173272000 (2xCD, Album) 5173272000 Alive In Seattle (2xSACD, Hybrid, E2H90287 Heart Epic, Legacy E2H90287 US 2003 Multichannel, Album) Universal Music Alive In Seattle DVD Video, 060252710057-9 Heart -

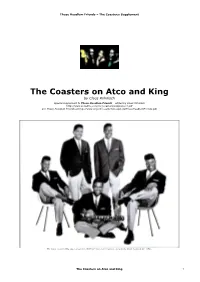

The Coasters on Atco and King by Claus Röhnisch

Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters: Supplement The Coasters on Atco and King by Claus Röhnisch Special supplement to Those Hoodlum Friends – edited by Claus Röhnisch http://www.angelfire.com/mn/coasters/supplement.pdf see Those Hoodlum Friends at http://www.angelfire.com/mn/coasters/ThoseHoodlumFriends.pdf The classic Coasters: Billy Guy, Carl Gardner, Will “Dub” Jones, Cornell Gunter, and guitarist Adolph Jacobs (in late 1958). The Coasters on Atco and King 1 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters: Supplement The Coasters in 2008: Ronnie Bright, Carl Gardner Jr, J.W. Lance, and Alvin Morse (with guitarist Thomas “Curley” Palmer). (photo: Denny Culbert, 2theAdvocate.com, Louisiana) The Coasters receiving their two Golden Records for the double-hit "Searchin´" / "Young Blood" on the Steve Allen TV-show on August 25, 1957. Gardner, Guy, Nunn, Allen, Hughes, and seated Jacobs. (from Cash Box magazine, September 14, 1957 issue). 2 The Coasters on Atco and King Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters: Supplement THE COASTERS on Atco and King The Coasters’ Atco recordings – Sessionography, featuring: “There’s A Riot Goin’ On: The Coasters On Atco” – Rhino Handmade 4-set CD RHM2 7740 (December 12, 2007) The Coasters’ recording line-ups are listed as headings. Carl Gardner, lead vocal unless otherwise indicated. The Coasters’ stage guitarists Adolph Jacobs, Albert “Sonny” Forriest, and Thomas “Curley” Palmer also worked in the studios with the vocal group (as shown on personnel listings). Recording location is valid until new location is listed. All unmarked labels are Atco. Only US original issues are listed – singles, EPs and LPs, and when originally not issued on any US single or LP, the first album issue (LP/CD). -

Man Rescued from Keansburi Nixon to Visit Europe

Man Rescued From Keansburi SEE STORY BE1 FINAL The Weather THEDAILY Sunny, mild today, high in low 70s inland. 60s along shore. EDITION Partly sunny and warm to- / 30 PAGES morrow. Monmouth County's Outstanding Home Newspaper TEN CENT$ VOL 95 NO. 201 RED BANK, NJ. MONDAY, APRIL 16,1973 •miHininiiHiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiimimiiiiniiiHiiiiiiniiiiiMniiuiiiiMiiiuiiiiiiiiiuuuu i inmiiuiiiiiiiiiiniu uiiiiiiiiiiiiiiium.iuii.iiiiimii.i tin iii.iiiu.HU.iiiM.iiiiiiiiii.HiiM.in.ii.Hin i»""'« iiiiiiiiimmiwwiii mm •••""» i«"M«MiiiiPiiiuiiiniiuu i nun Nixon to Visit Europe WASHINGTON (AP) - States by fall. As he began his second Washington, the President tot Fastening his attention on Eu- The President said French term, Nixon called 1973 "the vited a number of White rope, President Nixon plans a President Georges Pompidou year of Europe" and in- House news correspondents to fall visit to major NATO na- will visit the United States, dicated that he would devote the church service afteif tions for discussions on trade, but not necessarily Washing- more attention to soothing speaking at the annual corre- military aid and troop levels. ton, for conferences before some European frustrations spondents' association dinner Nixon told reporters yes- autumn. with recent U.S. economic Saturday night. terday he is preparing for the British Prime, Minister Ed- and military policies. The sermon was delivered autumn tour. Deputy Press ward Heath came to the by the Rev. Edward Victbr Nixon told newsmen of his Secretary Gerald L. Warren United States in early Febru- Hill, a black Baptist minister said later that the President ary for talks with Nixon. plans while standing in the re- from Los Angeles. -

The Coasters

The Coasters The Coasters are an American rhythm and blues/rock 1957 (all were recorded in Los Angeles). and roll vocal group who had a string of hits in the late "Yakety Yak" (recorded in New York), featuring King 1950s. Beginning with "Searchin'" and "Young Blood", Curtis on tenor saxophone, included the famous lineup of their most memorable songs were written by the songwrit- Gardner, Guy, Jones, and Gunter, became the act’s only ing and producing team of Leiber and Stoller.[1] Although national #1 single, and also topped the R&B chart. The the Coasters originated outside of mainstream doo-wop, next single, "Charlie Brown", reached #2 on both charts. their records were so frequently imitated that they be- It was followed by "Along Came Jones", "Poison Ivy" (#1 came an important part of the doo-wop legacy through for a month on the R&B chart), and "Little Egypt (Ying- the 1960s. Yang)". Changing popular tastes and a couple of line-up changes contributed to a lack of hits in the 1960s. During this 1 History time, Billy Guy was also working on solo projects, so New York singer Vernon Harrell was brought in to replace him for stage performances. Later members included Earl The Coasters were formed in October 1955 as a spin- “Speedo” Carroll (lead of the Cadillacs), Ronnie Bright off of the Robins, a Los Angeles-based rhythm and blues (the bass voice on Johnny Cymbal's "Mr. Bass Man"), group that included Carl Gardner and Bobby Nunn. The Jimmy Norman, and guitarist Thomas “Curley” Palmer.