Identifying the Block Pattern of Skopje's Old Bazaar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROSPEKT ITTF NOV.Cdr

OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER MACED TION ONIAN TABLE TENNIS ASSOCIA ITTF JUNIOR CIRCUIT S K O P J E 8 - 1 2 O c t 2 0 1 9 OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER IT ITTF JUNIOR CURCU OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER IT ITTF JUNIOR CURCU junior players during ITTF Junior Circuit. All players will be fighting for the titles in Skopje and that OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER ITT RCUIT F JUNIOR CU WELCOME TO SKOPJE, Millenium Cross The Millennium Cross is tall cross situated on Krstovar on top of Mountain Vodno over the city of Skopje. The cross is 66 meters tall which makes it the tallest object in the Republic of North Macedonia. It was built in 2002. This cross was built in honor of two thousand years of Christianity in North Macedonia and the advent of the new millennium. There is also a cable car cabins that lead to the Millennium Cross and serve as a panoramic view of the city and mountains. OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER ITT RCUIT F JUNIOR CU WELCOME TO SKOPJE, Mother Teresa-Memorial House Спомен куќа - Мајка Тереза Skopje Fortress Скопско кале Canyon Matka Кањон Матка Canyon Matka, is like a quick gateway from all the fuss and chaos in the capital. The genuine smells of the lively green nature,combined with the poetic sounds of the load, fresh river makes an atmosphere to die for! Grabbing a bite at the Matka restaurant by the water or taking a walk across the canyon, it is always a pleasurable experience. For the zen humans-a restaurant and bout trips.For the sporty ones-canoeing on the wild river or hiking.There are 10 caves you could see and the canyon also features two vertical pits, both roughly extending 35 meters.For the history explorers-the canyon area is home to several historic churches and monasteries. -

Art 03:Mise En Page 1.Qxd

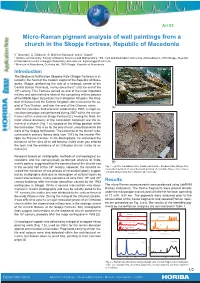

Art 03 Micro-Raman pigment analysis of wall paintings from a church in the Skopje Fortress, Republic of Macedonia V. Tanevska1, Lj. Džidrova2, B. Minčeva-Šukarova1 and O. Grupče1 1 Institute of Chemistry, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, “SS. Cyril and Methodius” University, Arhimedova 5, 1000 Skopje, Republic of Macedonia e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Museum of Macedonia, Ćurčiska bb, 1000 Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Introduction The Mediaeval fortification Skopsko Kale (Skopje Fortress) is si- tuated in the heart of the modern capital of the Republic of Mace- donia, Skopje, performing the role of a strategic centre of the Central Balkan Peninsula, mainly since the 6th until the end of the 19th century. This Fortress served as one of the most important military and administrative sites of the competing military powers of the Middle Ages: Byzantium; the II Bulgarian Kingdom; the King- dom of Samuel and the Serbian Kingdom, when it became the ca- pital of Tsar Dushan, and later the seat of the Ottoman rulers. (a) After the extensive field research conducted in 1967, a major ex- cavation campaign was performed during 2007 within the circum- ference of the mediaeval Skopje Fortress [1]. Among the finds, the most unique discovery of the excavation campaign are the re- mains of a church (Fig. 1.a), located at the hilltop position within the fortification. This is so far the only church unearthed within the walls of the Skopje fortification. The existence of the church is do- cumented in primary literary data from 1573 by the traveler Phi- lippe du Fresne-Canaye. -

1086 € 8 Days 14 Skopje to Dihovo 4 Walking Tours Europe #B1/2391

Full Itinerary and Tour details for 8-day Walking Tour Western Macedonia Level 4 Prices starting from. Trip Duration. Max Passengers. 1086 € 8 days 14 Start and Finish. Activity Level. Skopje to Dihovo 4 Experience. Tour Code. Walking Tours Europe #B1/2391 8-day Walking Tour Western Macedonia Level 4 Tour Details and Description Macedonia remains one of Europe’s last undiscovered areas. Being centrally located in the Balkans, this country is a crossroad between the East and West, Christianity and Islam, melting pot of civilizations, which reflects in its culture and overall way of life even today. During this adventurous journey you will experience firsthand Macedonia’s beautiful nature with walks in the areas of Skopje and the national parks of Mavrovo and Galicica. The tour also includes a day of exploration in the area of Ohrid - Macedonian UNESCO world cultural and natural heritage site. During the journey you will taste local cuisine typical for each area visited prepared by friendly locals, and combine the delicacies with premium Macedonian wines and spirits. Included in the Walking Tour: • Transportation throughout the journey (English speaking driver, fuel, pay tolls, parking incl.) • Experienced tour leader • Accommodation at hotels and family homes (as per program) • All meals (as per program; beverages excluded) at hotels/local restaurants/family homes/outdoor locations • Entrance fees in national parks / archaeological sites • 24/7 assistance Not Included in the tour: • Transfers to Macedonia • Optional meals and activities (boat trips, lunches) • Travel insurance • Tips • Personal expenses Minimum 4 people (ask us for price for 2 or 3 people) Departure dates on request - minimum 4 people Check Availability Book Online Now Send an Enquiry 2/6 8-day Walking Tour Western Macedonia Level 4 Day 2 Walking in the Skopje area (Mt. -

Turkish Studies International Periodical for the Languages, Literature and History of Turkish Or Turkic Volume 12/13, P

Turkish Studies International Periodical for the Languages, Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic Volume 12/13, p. 71-94 DOI Number: http://dx.doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.11755 ISSN: 1308-2140, ANKARA-TURKEY This article was checked by iThenticate. UNUTULMAYA YÜZ TUTMUŞ BİR TİCARET HANI: YENİ HAN Gülberk BİLECİK* ÖZET Makalenin konusunu oluşturan Yeni Han, Haliç kıyısı ve yamaçlarında hanlar bölgesi olarak isimlendirilen alanda, Tahtakale’de bulunmaktadır. Tahtakale ve çevresi, liman içi bir semt ve en önemli ticaret iskelelerinin hemen arkasında uzanan bir bölge olarak hem Bizans hem de Osmanlı dönemi boyunca ticaret alanı olma özelliğini devam ettirmiştir. Hasırcılar Caddesi üzerinde bulunan yapı, Tahmis Çıkmazı ve Fındıkçılar Sokağı ile çevrelenmiştir. Yaklaşık 1366.5 m2’lik bir alanı kaplamaktadır. Hasırcılar Hanı, Emin Hanı ve Tahmis Hanı gibi değişik isimlerle de anılmaktadır. Çalışmada ilk olarak Yeni Han’ın da içinde bulunduğu Tarihi Yarımada’daki ticaret bölgesi hakkında, fetih öncesi ve fetih sonrası olmak üzere kısa bir bilgi verilecektir. Fetihten sonra İstanbul’da görülen ticaret yapıları kısaca tanıtıldıktan sonra çalışmanın konusunu oluşturan Yeni Han’ın konumu, yeri ve günümüzdeki durumu incelenecektir. Yeni Han’ın inşa tarihi, yaptıranı ve mimarı hakkında kesin bir bilgi yoktur. Makalede binanın tarihlendirilmesine çalışılmıştır. Bunun için bölgede bulunan ve çeşitli yüzyıllara tarihlenen hanlar incelenmiştir. Birçok hanın duvar işçilikleri, plan ve cephe kuruluşları, avlu sayıları ve mimari ögeleri araştırılmıştır. Toplanan veriler ışığında sonuç olarak yapının 18. yüzyıla tarihlendirilmesi uygun görülmüştür. Bu makale ile bugüne kadar hakkında herhangi bir araştırma bulunmayan İstanbul’un önemli bir ticaret hanı, detaylı bir şekilde incelenmiş ve bilim dünyasına tanıtılmaya çalışılmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: İstanbul, Tarihi Yarımada, Ticaret, Han * Yrd. -

Urban Form at the Edge: Proceedings of ISUF 2013, Volume 1 1

Urban Form at the Edge: Proceedings of ISUF 2013, Volume 1 1 Urban Form at the Edge: Proceedings from ISUF 2013 will be published in two volumes. This volume is the first. Editors: Paul Sanders, Mirko Guaralda & Linda Carroli © Contributing authors, 2014 This publication is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permissions. Enquiries should be made to individual authors. All contributing authors assert their moral rights. First published in 2014 by: Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Creative Industries Faculty – School of Design in conjunction with International Seminar on Urban Form GPO Box 2434 Brisbane, QLD 4001 Australia QUT School of Design: https://www.qut.edu.au/creative- industries/about/about-the-faculty/school-of-design ISUF: http://www.urbanform.org ISBN 978-0-9752440-4-3 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: International Seminar on Urban Form (20th : 2013 : Brisbane, Queensland) Urban form at the edge : proceedings from ISUF2013. Volume 1 / Paul Sanders, Mirko Guaralda, Linda Carroli editors. 9780975244043 (ebook) (Volume 1) Cities and towns--Congresses. Sociology, Urban--Congresses. urban anthropology--Congresses. Sanders, Paul, editor. Guaralda, Mirko, editor. Carroli, Linda, editor. 307.76 All opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect views of the publishers and their associates. Permission -

The Panoramic Tour of Skopje

The Panoramic Tour of Skopje 22 April 2017 09:00 Departure from the conference center Professional and experienced licensed guide during the tours. Transportation by a comfortable AC non smoking Luxurious car / Van with professional driver. 20:00 Returning to the hotel Price: FREE During the Tour will visit the Historical Places Macedonia Square Stone Bridge Skopje Fortress Old Bazaar Skopje Ishak Bey Mosque Museum of The Macedonian Struggle (Skopje) Note: Only, the museums entrance fee and lunch will be paid by the participants. Historical Places Information 1. Macedonia Square It is located in the central part of the city, and it crosses the Vardar River. The Christmas festivals are always held there and it commonly serves as the site of cultural, political and other events. The independence of Macedonia from Yugoslavia was declared here by the country's first president, Kiro Gligorov. The square is currently under re- development and there are many new buildings around the square being constructed. The three main streets that merge onto the square are Maksim Gorki, Dimitar Vlahov and Street Macedonia. Dimitar Vlahov Street was converted into a pedestrian street in 2011. Maksim Gorki, while not a pedestrian zone, is lined with Japanese Cherry trees, whose blossoms in spring mark a week-long series of Asian cultural events. Finally, Macedonia Street, the main pedestrian street, connects Macedonia Square to the Old Railway Station (destroyed by the 1963 earthquake), which houses the City of Skopje Museum. Along Macedonia Street is the Mother Teresa Memorial House, which features an exhibit of art facts from Mother Teresa's life. -

Ottoman History of South-East Europe by Markus Koller

Ottoman History of South-East Europe by Markus Koller The era of Ottoman Rule, which began in the fourteenth century, is among the most controversial chapters of South-East European history. Over several stages of conquest, some of them several decades long, large parts of South-Eastern Europe were incorporated into the Ottoman Empire, or brought under its dominion. While the Ottomans had to surrender the territories north of the Danube and the Sava after the Peace Treaty of 1699, the decline of Ot- toman domination began only in the nineteenth century. Structures of imperial power which had been implemented in varying forms and intensity in different regions were replaced by emerging nation states in the nineteenth century. The development of national identities which accompanied this transformation was greatly determined by the new states distancing themselves from Ottoman rule, and consequently the image of "Turkish rule" has been a mainly negative one until the present. However, latest historical research has shown an increasingly differentiated image of this era of South-East European history. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Military and Political Developments 2. The Timar System 3. Ottoman Provincial Administration 1. Regional Differences in the Ottoman Provincial Administration 4. Islamisation 5. Catholic Christianity, Orthodox Christianity and Judaism 6. Urban Life 7. Appendix 1. Bibliography 2. Notes Indices Citation Military and Political Developments The Ottoman Empire had its roots in North-West Anatolia where in the thirteenth century the Ottoman Emirate was one of numerous minor Turkmen princedoms.1 The expansion of territory started under the founder of the dynasty, Osman (ca. -

Skopje Тop 10

A WALK THROUGH THE ETERNAL CITY SKOPJE ТOP 10 Scupi Skopje City Tour Canyon Matka 4 Near the city of Skopje, there are ruins of the 7 There is a double-decker panoramic bus in On just around 20 kilometres from Skopje, old ancient city of Scupi, an important centre Skopje which provides several tours around 1 from the time of the Roman Empire, which visit the canyon or, more precisely, the home the biggest attractions in the city. Its tour of the deepest underwater cave in Europe. you may visit. However, the most valuable starts from Porta Macedonia, near the The Canyon is the favourite place for lots of artifacts of this city are placed in the Macedonia square. climbers, kayakers, alpinists, cyclists and all Archeological museum of Macedonia. those who want to spend some time away Tauresium from the city, in the local restaurant. 8 This locality, near the village Taor, is the birth The Old Bazaar place of the great Emperor Justinianus I, who is Millennium Cross famous for bringing the law reforms on which even 5 The kaldrma of the Old Bazaar in the present Roman citizen law is based on. 2 The city bus number 25 shall take you to Middle the centre of the city is going to Vodno and by the ropeway you can get to the take you to the most beautiful top of Vodno mountain, where not only will you souvenirs, antiquities and Burek see the highest cross in the world, but you will handmade works of art, you will see The burek is a pie filled either with meat, cheese, spinach also enjoy the most beautiful view of the city. -

T E H N O L a B Ltd Skopje

T E H N O L A B Ltd Skopje Environment, technology, protection at work, nature PO Box.827, Jane Sandanski 113, Skopje tel./fax: ++389 2 2 448 058 / ++389 70 265 992 www. tehnolab.com.mk; e-mail: [email protected] Study on Wastewater Management in Skopje ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) STUDY FINAL REPORT October, 2008 Skopje Part II: A6-43 Tehnolab Ltd.—Skopje EIA Study WWTP, Skopje Ordered by : Japan International Cooperation Agency Study Team Project : Study on Wastewater Management in Skopje File : EIA Study (Main Report and Annexes) Prepared by : Tehnolab Ltd, Skopje Team leader : M.Sc. Magdalena Trajkovska Trpevska (B.Sc. Chemical engineer) Experts involved : Ph. D. Stanislava Dodeva (B.Sc. Civil Hydro engineer), Environmental expert Ljubomir Ivanovski (B.Sc. Energy engineer) - Environmental expert, cooperator of team leader Andrijana Veljanoska (B.Sc. Environmental engineer) (team leader assistant) Borce Aleksov (B.Sc. Chemical engineer) - Environmental expert, co-operator of team leader Ph.D. Vlado Matevski , Expert Biologist (Expert regarding Flora) Ph. D. Sveto Petkovski, Expert Biologist (Expert regarding Fauna) Ph. D. Branko Micevski, Expert Biologist (Expert regarding endemic Bird species) Ph. D. Jelena Dimitrijevic (B.Sc. Techology engineer), Expert regarding social environmental aspects Date: October 2008 "TEHNOLAB" Ltd Skopje Company for technological and laboratory researches projections and services Manager: M.Sc. Magdalena Trajkovska Trpevska chemical engineer Part II: A6-44 Tehnolab Ltd.—Skopje EIA Study -

Albania Macedonia Grecia

Piazzale Giulio Pastore 6 – 00144 Roma Tel. 06.807.87.28 / 807.09.74 fax 06.808.29.64 www.cralinailroma.it ALBANIA MACEDONIA GRECIA 18 agosto - 25 agosto (8 giorni 7 notti) In Breve Una civiltà piena di fascino e un paese dai tratti unici sono il risultato di un singolare intreccio fra le culture greca, serba, bulgara e albanese, e fra le religioni cristiano-ortodossa e islamica. Questa terra merita ben più di una visita di passaggio. Monasteri medievali, bazar turchi logorati dal tempo, chiese ortodosse e centri commerciali dell’era spaziale. E ancora: il mormorio delle cornamuse locali, gli spiedi di carne alla turca e il balcanico burek (una torta salata ripiena di formaggio o di carne). Paesaggi verdeggianti fino all’inverosimile e di una bellezza che toglie il respiro; popoli ospitali e accoglienti verso i visitatori. Paesi che hanno una forte tradizione nelle arti e un grande background culturale. Il focus qui è su arte, architettura, musica e poesia. Paesi che hanno anche una storia incredibile, che viene spesso celebrata negli edifici storici e nelle innumerevoli chiese. Durante tutto l’anno si svolgono Festival per celebrare, le arti e le tradizioni locali. Quota a persona in camera doppia € 1.130,00 Gruppo minimo: 20 persone Supplemento singola € 150,00 1° giorno: ITALIA – TIRANA – OHRID Partenza da Roma per Tirana con volo di linea Alitalia. Arrivo a Tirana ore 10.50 e incontro con la guida e inizio city tour della città. Pranzo in ristorante. Al termine partenza in direzione di Ohrid. Sistemazione in hotel, cena e pernottamento. -

T2. COMPETITION PROJECT PROGRAM T.2.1 / Context of The

T2. COMPETITION PROJECT PROGRAM T.2.1 / Context of the competition The Competition for preparation of preliminary urban and architectural development design for arrangement of the Kale Hill in Skopje constitutes an integral part of the project Kale – Cultural Fortress, organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje, with the goal of encouraging the revitalization and spatial arrangement of the Kale Hill into an attractive and vibrant city attraction with various cultural, educational and recreational functions. T.2.2/ Current state Two important cultural monuments dominate the Kale Hill: The mediaeval fortress – Kale and the Museum of Contemporary Art in (https://msu.mk/). The exceptional historic and contemporary significance of these two imposing structures for the City of Skopje have been largely diminished due to many years of neglect of the broader location of the Kale Hill. The uncultivated and barely accessible areas of greenery and waste, poorly approachable lighting infrastructure, as well as the many temporary substandard structures divide the Kale Hill into multiple functionally incompatible, isolated and secluded spatial fragments. Feeling the detrimental consequences of this situation regarding the availability to the public on one hand, while being aware of the enormous potential of this space in possible support and expansion of the diversity and attractiveness of our programs on the other hand, the team of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje, by announcing this competition for preliminary design proposals, encourages bold and innovative, but at the same time simple and feasible ideas and concepts for cultivating the Kale Hill into “cultural fortress” and the public interest. -

Values of the Historic Urban Form of Skopje's Old Bazaar Based On

Values of the Historic Urban Form of Skopje's Title Old Bazaar Based on Analysis of the Ottoman Urban Strategy Author(s) Krstikj, Aleksandra Citation Issue Date Text Version ETD URL https://doi.org/10.18910/34483 DOI 10.18910/34483 rights Note Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University Doctoral Dissertation Values of the Historic Urban Form of Skopje’s Old Bazaar Based on Analysis of the Ottoman Urban Strategy Krstikj Aleksandra December・2013 Graduate School of Engineering Osaka University Doctoral Dissertation Values of the Historic Urban Form of Skopje’s Old Bazaar Based on Analysis of the Ottoman Urban Strategy Krstikj Aleksandra December・2013 Graduate School of Engineering Osaka University Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this study to my uncle Aleksandar Kondev. It was him who first sparked my interest in the history of my hometown Skopje, where our family has lived and worked for generations. His stories, together with time spent in my grandfather’s shop in the Old Bazaar, formed my strong personal connection with the place. During my university years at Faculty of Architecture-Skopje, I got interested in our Macedonian architectural and urban heritage owing to the inspiring lectures of my Professor Jasmina Hadzieva. Later, with her support, I made the first steps in the research of Skopje’s Bazaar urban environment and prepared my bachelor thesis. Several years after, the remarkable opportunity to do research and study in Japan renew my professional interest in Skopje’s Bazaar. With amazing dedication and kindness, my Professor Hyuga Susumu from the Kyoto Institute of Technology made possible four field surveys in Skopje’s Bazaar with the graduate students from his laboratory.