Alternative Modernities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED January 13, 2015 January 7, 2015 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] ALAN GILBERT AND THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC Alan Gilbert To Conduct SILK ROAD ENSEMBLE with YO-YO MA Alongside the New York Philharmonic in Concerts Celebrating the Silk Road Ensemble’s 15TH ANNIVERSARY Program To Include The Silk Road Suite and Works by DMITRI YANOV-YANOVSKY, R. STRAUSS, AND OSVALDO GOLIJOV February 19–21, 2015 FREE INSIGHTS AT THE ATRIUM EVENT “Traversing Time and Trade: Fifteen Years of the Silkroad” February 18, 2015 The Silk Road Ensemble with Yo-Yo Ma will perform alongside the New York Philharmonic, led by Alan Gilbert, for a celebration of the innovative world-music ensemble’s 15th anniversary, Thursday, February 19, 2015, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, February 20 at 8:00 p.m.; and Saturday, February 21 at 8:00 p.m. Titled Sacred and Transcendent, the program will feature the Philharmonic and the Silk Road Ensemble performing both separately and together. The concert will feature Fanfare for Gaita, Suona, and Brass; The Silk Road Suite, a compilation of works commissioned and premiered by the Ensemble; Dmitri Yanov-Yanovsky’s Sacred Signs Suite; R. Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration; and Osvaldo Golijov’s Rose of the Winds. The program marks the Silk Road Ensemble’s Philharmonic debut. “The Silk Road Ensemble demonstrates different approaches of exploring world traditions in a way that — through collaboration, flexible thinking, and disciplined imagination — allows each to flourish and evolve within its own frame,” Yo-Yo Ma said. -

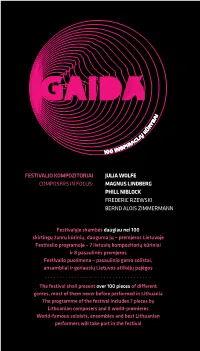

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio Between the US and Syria

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Beau Bothwell All rights reserved ABSTRACT Song, State, Sawa: Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell This dissertation is a study of popular music and state-controlled radio broadcasting in the Arabic-speaking world, focusing on Syria and the Syrian radioscape, and a set of American stations named Radio Sawa. I examine American and Syrian politically directed broadcasts as multi-faceted objects around which broadcasters and listeners often differ not only in goals, operating assumptions, and political beliefs, but also in how they fundamentally conceptualize the practice of listening to the radio. Beginning with the history of international broadcasting in the Middle East, I analyze the institutional theories under which music is employed as a tool of American and Syrian policy, the imagined youths to whom the musical messages are addressed, and the actual sonic content tasked with political persuasion. At the reception side of the broadcaster-listener interaction, this dissertation addresses the auditory practices, histories of radio, and theories of music through which listeners in the sonic environment of Damascus, Syria create locally relevant meaning out of music and radio. Drawing on theories of listening and communication developed in historical musicology and ethnomusicology, science and technology studies, and recent transnational ethnographic and media studies, as well as on theories of listening developed in the Arabic public discourse about popular music, my dissertation outlines the intersection of the hypothetical listeners defined by the US and Syrian governments in their efforts to use music for political ends, and the actual people who turn on the radio to hear the music. -

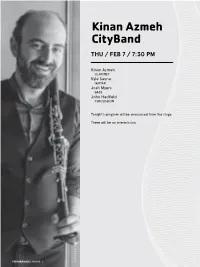

Kinan Azmeh Cityband THU / FEB 7 / 7:30 PM

Kinan Azmeh CityBand THU / FEB 7 / 7:30 PM Kinan Azmeh CLARINET Kyle Sanna GUITAR Josh Myers BASS John Hadfield PERCUSSION Tonight’s program will be announced from the stage. There will be no intermission. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 6 Tsang Connie by Photo ABOUT THE ARTIST KINAN AZMEH (CLARINET) Hailed as a “virtuoso” and “intensely soulful” by The New York Times and “spellbinding” by The New Yorker, Kinan’s utterly distinctive sound, crossing different musical genres, has gained him international recognition as a clarinetist and composer. Kinan was recently composer-in-residence with Classical Movements for the 2017/18 season. Kinan has toured the world as a soloist, composer and improviser. Notable appearances include Opera Bastille, Paris; Tchaikovsky Grand Hall, Moscow; Carnegie Hall and the UN's general assembly, New York; the Royal Albert Hall, London; Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires; der Philharmonie, Berlin; the Library of Congress and The Kennedy Center, Washington, D.C.; the Mozarteum, Salzburg, Austria; Elbphilharmonie, Hamburg; and the Damascus Opera His discography includes three albums Kinan is a graduate of New York's House for its opening concert in his with his ensemble, Hewar, several Juilliard School as a student of native Syria. soundtracks for film and dance, a duo Charles Neidich, both of the album with pianist Dinuk Wijeratne and Damascus High Institutes of Music He has appeared as soloist with the an album with his New York Arabic/Jazz where he studied with Shukry Sahwki, New York Philharmonic, the Seattle quartet, the Kinan Azmeh CityBand. Nicolay Viovanof and Anatoly Moratof, Symphony, the Bavarian Radio He serves as artistic director of the and of Damascus University’s School Orchestra, the West-Eastern Divan Damascus Festival Chamber Players, of Electrical Engineering in his native Orchestra, the Qatar Philharmonic and a pan-Arab ensemble dedicated to Syria. -

The Rose Art Museum Presents Syrian-Armenian Artist Kevork

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Nina J. Berger, [email protected] 617.543.1595 THE ROSE ART MUSEUM PRESENTS SYRIAN-ARMENIAN ARTIST KEVORK MOURAD’S IMMORTAL CITY “Culture Cannot Wait” program brings experts in preserving cultural heritage to Brandeis campus (Waltham, Mass.) – The Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University presents Immortal City, an exhibition of new paintings by acclaimed Syrian-Armenian artist Kevork Mourad created in response to the war in Syria and the destruction of the artist’s beloved city of Aleppo, September 8, 2017 – January 21, 2018. A public opening reception to celebrate the museum’s fall exhibition season will be held 6–9 pm on Saturday, October 14. Kevork Mourad (b. Syria 1970) is known for paintings made spontaneously in collaboration with composers, dancers, and musicians. Of Armenian descent, Mourad performs in his art both a vital act of remembering and a poetic gesture of creativity in the face of tragedy, as he mediates the experience of trauma through finely wrought, abstracted imagery that celebrates his rich cultural heritage even as he mourns its loss. Mourad’s paintings ask viewers to stop and bear witness, to see the fragments of a culture destroyed – textiles, ancient walls, Arabic calligraphy, and bodies crushed by war. Using a unique method that incorporates monoprinting and his own technique of applying paint with one finger in a sweeping gesture, Mourad produces paintings that are fantastical, theatrical, and lyrical, the line reflecting the music that is such an integral part of his practice. An 18th-century etching from the Rose’s permanent collection by Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranisi will accompany Mourad’s work and locate Mourad's practice within a centuries-old artistic interest and fascination with the city in ruins. -

Old and New Works on Orchestra Program | Town Topics

1/7/2020 Old and New Works On Orchestra Program | Town Topics December 18, 2019 Old and New Works On Orchestra Program WORLD PREMIERE: Clarinetist Kinan Azmeh is soloist in a new work by Saad Haddad, on the Princeton Symphony Orchestra’s programs January 18 and 19. (Photo by Martina Novak) On Saturday, January 18 at 8 p.m. and Sunday, January 19 at 4 p.m. in Richardson Auditorium, the Princeton Symphony Orchestra (PSO) performs Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s popular work Scheherazade, Op. 35 on a program with the world premiere of composer Saad Haddad’s Clarinet Concerto. A commission of the PSO and the Barlow Endowment for Music Composition at Brigham Young University, the concerto features Syrian clarinetist Kinan Azmeh. Jacques Ibert’s Escales (Ports of Call) completes the program to be conducted by Edward T. Cone Music Director Rossen Milanov. Rimsky-Korsakov was influenced by explorer Richard Francis Burton’s 1885 translation of One Thousand and One Nights (the Arabian Nights) enough to craft a symphonic suite centered on its heroine. Ibert’s Escales recounts the sights and sounds of a Mediterranean coastal excursion, and composer Saad Haddad draws upon his Middle Eastern ancestry to create a work conveying a universal spirit of cooperation among fellow human beings. His new concerto is dedicated to the memory of his grandfather, who led Haddad’s mother and her extended family away from war-torn Lebanon to the United States. This is the second world premiere of a work by Haddad, co- commissioned by the PSO, and the third work overall of his performed by the orchestra since January 2017. -

Café Damas Kinen Azmeh

New York Philharmonic Presents their many complexities and hidden hyper- Café Damas, which receives its World activity, primarily through timbre. The second Premiere in this performance, draws on movement is centered around the role of Azmeh’s relationship to the New York Phil- spatial and temporal organization of musical harmonic, “the Biggest Band in New York” ideas as well as the physical and contextual (with which he has worked twice before, questioning of music repetition. The third once as a performer and once as a com- movement both summarizes the two pre- poser), as well as his relationship to his vious movements and adds to them other hometown of Damascus. He said: elements dear to me: virtual polyphony (the il- lusion of a bigger instrumental force), internal I wanted to bring the musicians of the and external counterpoint, stylistic plurality at Philharmonic closer to my home, both the service of the music material, and close conceptually and culturally. This work is structuring of transitions and proportions. inspired by the idea of an imaginary tra- ditional house band in a 1960s café in Composer, clarinet soloist, and improviser Damascus, a band that has not changed Kinan Azmeh was born in Damascus, Syria, personnel nor location for decades and and lives in New York City. He is the rare mu- continued to play in spite of all. Musically sician who elegantly shifts roles from creator speaking, this piece enjoys a rather tra- to interpreter, writing for and performing with ditional form that opens with a Taqasi¯m some of the most iconic musicians alive to- (melodic improvisation), which introduc- day, including frequent collaborator Yo-Yo Ma. -

Zvidance DABKE

presents ZviDance Sunday, July 12-Tuesday, July 14 at 8:00pm Reynolds Industries Theater Performance: 50 minutes, no intermission DABKE (2012) Choreography: Zvi Gotheiner in collaboration with the dancers Original Score by: Scott Killian with Dabke music by Ali El Deek Lighting Design: Mark London Costume Design: Reid Bartelme Assistant Costume Design: Guy Dempster Dancers: Chelsea Ainsworth, Todd Allen, Alex Biegelson, Kuan Hui Chew, Tyner Dumortier, Samantha Harvey, Ying-Ying Shiau, Robert M. Valdez, Jr. Company Manager: Jacob Goodhart Executive Director: Nikki Chalas A few words from Zvi about the creation of DABKE: The idea of creating a contemporary dance piece based on a Middle Eastern folk dance revealed itself in a Lebanese restaurant in Stockholm, Sweden. My Israeli partner and a Lebanese waiter became friendly and were soon dancing the Dabke between tables. While patrons cheered, I remained still, transfixed, all the while envisioning this as material for a new piece. Dabke (translated from Arabic as "stomping of the feet") is a traditional folk dance and is now the national dance of Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and Palestine. Israelis have their own version. It is a line dance often performed at weddings, holidays, and community celebrations. The dance strongly references solidarity, and traditionally only men participated. The dancers, linked by hands or shoulders, stomp the ground with complex rhythms, emphasizing their connection to the land. While the group keeps rhythm, the leader, called Raas (meaning "head"), improvises on pre-choreographed movement phrases. He also twirls a handkerchief or string of beads known as a Masbha. When I was a child and teenager growing up in a Kibbutz in northern Israel, Friday nights were folk dance nights. -

Engagement: Coptic Christian Revival and the Performative Politics of Song

THE POLITICS OF (DIS)ENGAGEMENT: COPTIC CHRISTIAN REVIVAL AND THE PERFORMATIVE POLITICS OF SONG by CAROLYN M. RAMZY A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Carolyn Ramzy (2014) Abstract The Performative Politics of (Dis)Engagment: Coptic Christian Revival and the Performative Politics of Song Carolyn M. Ramzy A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Music, University of Toronto 2014 This dissertation explores Coptic Orthodox political (dis)engagement through song, particularly as it is expressed through the colloquial Arabic genre of taratil. Through ethnographic and archival research, I assess the genre's recurring tropes of martyrdom, sacrifice, willful withdrawal, and death as emerging markers of community legitimacy and agency in Egypt's political landscape before and following the January 25th uprising in 2011. Specifically, I explore how Copts actively perform as well as sing a pious and modern citizenry through negations of death and a heavenly afterlife. How do they navigate the convergences and contradictions of belonging to a nation as minority Christian citizens among a Muslim majority while feeling that they have little real civic agency? Through a number of case studies, I trace the discursive logics of “modernizing” religion into easily tangible practices of belonging to possess a heavenly as well as an earthly nation. I begin with Sunday Schools in the predominately Christian and middle-class neighborhood of Shubra where educators made the poetry of the late Coptic Patriarch, Pope Shenouda III, into taratil and drew on their potentials of death and withdrawal to reform a Christian moral interiority and to teach a modern and pious Coptic citizenry. -

My Voice Is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics Of

MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance David A. McDonald Duke University Press ✹ Durham and London ✹ 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Cover by Heather Hensley. Interior by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data McDonald, David A., 1976– My voice is my weapon : music, nationalism, and the poetics of Palestinian resistance / David A. McDonald. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5468-0 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5479-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Palestinian Arabs—Music—History and criticism. 2. Music—Political aspects—Israel. 3. Music—Political aspects—Gaza Strip. 4. Music—Political aspects—West Bank. i. Title. ml3754.5.m33 2013 780.89′9274—dc23 2013012813 For Seamus Patrick McDonald Illustrations viii Note on Transliterations xi Note on Accessing Performance Videos xiii Acknowledgments xvii introduction ✹ 1 chapter 1. Nationalism, Belonging, and the Performativity of Resistance ✹ 17 chapter 2. Poets, Singers, and Songs ✹ 34 Voices in the Resistance Movement (1917–1967) chapter 3. Al- Naksa and the Emergence of Political Song (1967–1987) ✹ 78 chapter 4. The First Intifada and the Generation of Stones (1987–2000) ✹ 116 chapter 5. Revivals and New Arrivals ✹ 144 The al- Aqsa Intifada (2000–2010) CONTENTS chapter 6. “My Songs Can Reach the Whole Nation” ✹ 163 Baladna and Protest Song in Jordan chapter 7. Imprisonment and Exile ✹ 199 Negotiating Power and Resistance in Palestinian Protest Song chapter 8. -

5,000-Year-Old Echoes of Humanity: Baalbek, Lebanon a Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed By: Carolyn J

5,000-year-old Echoes of Humanity: Baalbek, Lebanon A Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed by: Carolyn J. Fulton Tacoma Public Schools, Tacoma, Washington Summary: Students will compare and contrast two types (folk and art) music found in Lebanon, sing and play a simple song in Arabic, and dance the national dance called the Dabke. Suggested Grade Levels: 3-5, 6-8, 9-12 Country: Lebanon Region: The Middle East Culture Group: Lebanese Genre: Folk Music and Modern Art Music Instruments: Voice, body percussion, Orff Instruments, Recorders Language: English and Arabic Co-Curricular Areas: Geography, History, Physical Education National Standards: 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 9 Prerequisites: None Objectives: Students will listen and compare two contrasting pieces of music from Lebanon for timbre, melodic and rhythmic differences. Students will sing, play on instruments, and move to traditional Lebanese music. Material: Maps of World, Mediterranean, and Lebanon Afif Bulos Sings Songs of Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan” FW08816 (excerpt “Tafta Hindi,” tract 101) Download the PDF liner notes for information. Arabic and Druse Music,” FW04480, excerpt “Druse Festival,” (tract 205) Download the PDF liner notes for information. The Baalbek Folk Festival, MON71383, download both sections of music and the PDF liner notes with explanation of the program. Body percussion, Voice, Orff Xylophone (or suitable substitutes) and Recorder Lesson Segments: 1. Listen to 5,000 year-old Echoes from Baalbek, Lebanon and Compare! (National Standards 6, 8, 9) 2. An Ancient Song Sung Our Way (National Standards 1, 8, 9) 3. An Ancient Song Played on Our Instruments (Standards 1, 2, 8, 9 ) 4. -

Habibi - a Multi Dialect Multi National Arabic Song Lyrics Corpus

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 1318–1326 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Habibi - a multi Dialect multi National Arabic Song Lyrics Corpus Mahmoud El-Haj School of Computing and Communications Lancaster University United Kingdom [email protected] Abstract This paper introduces Habibi the first Arabic Song Lyrics corpus. The corpus comprises more than 30,000 Arabic song lyrics in 6 Arabic dialects for singers from 18 different Arabic countries. The lyrics are segmented into more than 500,000 sentences (song verses) with more than 3.5 million words. I provide the corpus in both comma separated value (csv) and annotated plain text (txt) file formats. In addition, I converted the csv version into JavaScript Object Notation (json) and eXtensible Markup Language (xml) file formats. To experiment with the corpus I run extensive binary and multi-class experiments for dialect and country-of-origin identification. The identification tasks include the use of several classical machine learning and deep learning models utilising different word embeddings. For the binary dialect identification task the best performing classifier achieved a testing accuracy of 93%. This was achieved using a word-based Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) utilising a Continuous Bag of Words (CBOW) word embeddings model. The results overall show all classical and deep learning models to outperform our baseline, which demonstrates the suitability of the corpus for both dialect and country-of-origin identification tasks. I am making the corpus and the trained CBOW word embeddings freely available for research purposes.