The Broad: Class Hatred, Concentrated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and the Broad Art Founda- Tion, Have Assets of $2.7 Billion

ELI BROAD is a renowned business Eli and leader who built two Fortune 500 companies Edythe from the ground up over a five-decade Broad career in business. He is the founder-chairman Founders of of both SunAmerica Inc. and KB Home (formerly Kaufman and Broad Home The Broad Foundations Corporation). Founding partners Today, Eli Broad and his wife, Edythe, are devoted to philanthropy as founders of the Broad Institute of The Broad Foundations, which they established to advance entrepreneurship of MIT and Harvard for the public good in education, science, and the arts. The Broad Foundations, which include The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and The Broad Art Founda- tion, have assets of $2.7 billion. The Broads’ investments in scientific and medical research are focused on three areas: human genomics, stem cell research, and inflammatory bowel disease. In an unprecedented partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technol- ogy, Harvard University, and the Whitehead Institute, the Broads in June 2003 announced the $100 million founding gift to create The Eli and Edythe Broad Institute for biomedical research. The institute’s aim is to realize the promise of the human genome to revolutionize clinical medicine and to make knowledge freely available to scientists around the world. They gave a second $100 million gift to the Broad Institute in 2005, and in 2008, with the Broad Institute firmly established as the world’s leading genomics and biomedical research institute, they gave $400 million to create an endowment that will make the institute permanent. In 2013, they gave another $100 million, bringing their total investment in the Broad Institute to $800 million. -

Bcam at Lacma

BCAM AT LACMA The Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM), opening February 16, 2008, is the centerpiece of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s (LACMA) Transformation—an ambitious program of expansion and renovation. Designed by Renzo Piano, founder, Renzo Piano Building Workshop, BCAM has been made possible thanks to a $60 million donation from Eli and Edythe Broad, including $50 million to the museum’s capital campaign and a pledge to cover the cost of the building over $50 million. The remaining $10 million was donated to fund acquisitions and was used in part in 2007 to purchase Richard Serra’s monumental sculpture Band (2006). Mr. Broad is a longtime LACMA Trustee, and he and Mrs. Broad are among the world’s most generous philanthropists, with interests that include the arts, education, and science. The three-story BCAM includes 60,000 square feet of exhibition space—one of the largest column-free art spaces in the United States— designed specifically for The Broad Contemporary Art Museum at LACMA the display of contemporary art. Included in the initial installation are some 160 works from the renowned collection of The Broad Art Foundation and the Broads’ personal collection, as well as forty works from LACMA’s own holdings in contemporary art and from other lenders. LACMA Director Michael Govan states, “The creation of BCAM greatly expands LACMA’s contemporary art program, both enriching the experience of its historical collections and placing LACMA in a position of prominence in the area of contemporary art among encyclopedic museums. We are additionally pleased that BCAM will enable us to show the work of several key artists in great depth, providing an exceptionally rewarding experience for visitors. -

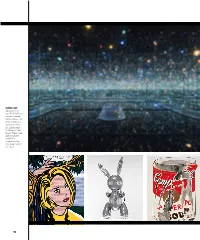

On the Scene at Coachella 2016 ICONIC ART (Clockwise from Top

ICONIC ART (Clockwise from top) You’ll find Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrored Room - The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away,” Roy Lichtenstein’s “I...I’m Sorry!,” Jeff Koons’ “Rabbit” and Andy Warhold’s “Small Torn Campbell’s Soup Can (Pepper Pot) at The Broad. Mark On the scene at Coachella 2016 98 Making a THESE FOUR GREAT SHAPERS EXPLAIN HOW THEY ARE PROGRESSING THE ART SCENE IN LOS ANGELES, THE CITY OF CONTINUOUS YOUTH AND ADAPTATION MaBY MARINE TANGUY rk There is no question that the current art world is evolving. From the rise of startups challenging the existing gallery model to a possible regulation of the market, we are entering a new era in the field. As always, with change, there are those who embrace it and those who fear it. But while the renowned art scenes of London and New York struggle to break their tradition and pre-establishment, L.A. is stepping up and becoming a lab for innovation and experimentation. Here’s to the bold and the visionaries—we have a lot to learn from them. PHOTOS COURTESY OF YAYOI KUSAMA/DAVID ZWIRNER, ROY LICHTENSTEIN/ ZWIRNER, ROY KUSAMA/DAVID OF YAYOI COURTESY PHOTOS STUDIO AND M. PARKER JEFF KOONS/DOUGLAS STUDIO, DOUGLAS M. PARKER INC./ ARTS, THE VISUAL FOR FOUNDATION WARHOL ANDY WARHOL/THE ANDY CAMPBELL TRADEMARKS USED WITH PERMISSION OF ARIST RIGHTS SOCIETY, CAMPBELL SOUP COMPANY 99 THE LOS ANGELES ART COLLECTORS ing ones, Edythe responds, “We have a long cessible to the public, so we decided to build ELI AND EDYTHE BROAD history of supporting public museums—Eli The Broad, endow it, fill it with our collection The Broads have about 2,000 works in was the founding chairman of MOCA and a and offer free general admission as a gift to their collection, one of the most prominent life trustee of MOCA, LACMA, MOMA. -

Oral History Interview with Eli Broad, 2012 Jan. 30-April 16

Oral history interview with Eli Broad, 2012 Jan. 30-April 16 Funding for this interview was provided by Barbara Fleischman. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Eli Broad on 2012 January 30 and April 16. The interview took place at the Frick Collection and at the Broad's home in New York, NY, and was conducted by Avis Berman for the Archives of American Art and the Center for the History of Collecting in America at the Frick Art Reference Library of The Frick Collection. Avis Berman reviewed the transcript in 2012. Swati Pandey, Director of Communications for the Eli and Edith Broad Foundation, reviewed the transcript in 2019. Their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials (Pandey's appear under –EB). This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview AVIS BERMAN: This is Avis Berman, interviewing Eli Broad for the Frick Collection Library, New York, NY, and the Archives of American Art Oral History Program, Washington, DC, on January 30, 2012, at the Frick Collection. Mr. Broad, I start this way with everyone. Would you please state your full name and date of birth? ELI BROAD: Eli Broad; June 6, 1933. AVIS BERMAN: I want to start briefly with Detroit. And I know you were not collecting there, but I wondered, in your family, what the interest in culture was, or if you had any mentors in that regard, or in music. -

Broad Foundation 95-4686318

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS I As Filed Data - I DLN: 93491315003366 OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 2015 Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury ► ► Information about Form 990 - PF and its instructions is at www .irs.gov/form99OPf . • • ' Internal Revenue Service For calendar year 2015 , or tax year beginning 01-01-2015 , and ending 12-31-2015 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE ELI AND EDYTHE BROAD FOUNDATION 95-4686318 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) BTelephone number (see instructions) 2121 AVENUE OF THE STARS NO 3000 (310) 954-5026 City or town, state or province , country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here ► LOS ANGELES, CA 90067 P G Check all that apply [Initial return [Initial return former public charity of a D 1. Foreign organizations , check here ► F-Final return F-A mended return P F-Address change F-Name change 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach computation ► E If private foundation status was terminated H Check type of organization [Section 501( c)(3) exempt private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► F Section 4947 (a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation IFair market value of all assets at end ]Accounting method [Cash [Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Pa,t II, col (c), [Other( specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ► F Ime 1,842 , 260,094 (Part I, column (d) must be on cash basis Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (d) Revenue and Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b), (c), and (d) may not Net investment Adjusted net expenses per for charitable necessarily equal the amounts n column (a) (see (b) income (c) income instructions)) (a) books purposes (cash basis only) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc , received (attach schedule) . -

Eli Broad Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cc156v No online items Eli Broad papers Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Bucher and Megan Hahn Fraser with assistance from Kelly Besser, 2015; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé.. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Finding aid last modified on 25 April 2016. Eli Broad papers 2235 1 Title: Eli Broad papers Collection number: 2235 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 26.8 linear ft.(16 record cartons, 10 document boxes, 2 flat boxes, and 6 oversize flat boxes) Date: 1957-2011 Abstract: Eli Broad is an American entrepreneur and philanthropist. His philanthropy related to art and education in Los Angeles includes important contributions to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Broad Art Center at UCLA, and the Walt Disney Concert Hall. The papers include event files, business files, photographs and home movies, materials related to Broad's philanthropy, press clippings, and awards. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Broad, Eli Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Eli Broad Papers (Collection 2235). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. -

Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation–Education 10900 Wilshire Boulevard Science Twelfth Floor Los Angeles,California 90024 Education T 310.954.5050 F 310.954.5051

411957M1_r2 3/4/08 3:37 PM Page 1 The Broad Foundations The Broad Foundations 2008 The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation–Education 10900 Wilshire Boulevard science Twelfth Floor Los Angeles,California 90024 education T 310.954.5050 F 310.954.5051 [email protected] www.broadfoundation.org The Eli and Edythe Broad civic Foundation–Scientific | Medical Research arts 10900 Wilshire Boulevard Twelfth Floor Los Angeles,California 90024 T 310.954.5091 F 310.954.5092 [email protected] www.broadmedical.org The Broad Art Foundation 3355 Barnard Way Santa Monica,California 90405 T 310.399.4004 F 310.399.7799 2008 [email protected] www.broadartfoundation.org ENTREPRENEURSHIP FOR THE PUBLIC GOOD IN EDUCATION, SCIENCE ANDTHE ARTS 411957M1_r1 2/27/08 2:21 PM Page 2 2008The Broad Foundations “Those of us who have been blessed with time, talent and treasure have an obligation to reach down, back and across and help those who are less fortunate and to improve our communities.” FORMERU.S. SECRETARY OF STATE AND RET. GEN. COLIN POWELL, DELIVERING THE KEYNOTE ADDRESS AT THE ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE 2007 BROAD PRIZE FOR URBAN EDUCATION The Mission of The Broad Foundations Transforming K-12 urban public education through better governance, management, labor relations and competition Making significant contributions to advance major scientific and medical research Fostering public appreciation of contemporary art by increasing access for audiences worldwide Leading and contributing to major civic projects in Los Angeles 2008 10 Education 30 Scientific | Medical Research 40 Art 52 Civic Initiatives 60 Commitments 72 Financial Statement 74 The Broad Team 76 About the Founders 411957M2_r5 4/2/08 11:11 AM Page 4 Letter from the Directors Impact It’s the goal of every foundation and certainly the driving force behind the work we do every day. -

Broad Impact

Broad Impact An Interview with Eli Broad, Founder, The Broad Foundations EDITORS’ NOTE After working for The Broad Foundations are fo- And we created the biggest prize in public two years as an accountant, Eli cused on transforming K-12 pub- education, the $1-million Broad Prize. We have Broad founded a home-building lic education. What impact have also supported proven public charter schools. company with Donald Kaufman. you had in this area and why has We’ve made some progress, though there In 1971, the Kaufman and Broad it been such a challenge to cre- is still much work to be done. Home Corporation acquired a ate true reform with such wide- What is needed to create real K-12 small life insurance company for spread emphasis on it? reform? $52.1 million that they eventually Eleven years ago, after we sold First, we need a longer school day and transformed into a retirement sav- SunAmerica to AIG and came into a school year, because our kids are being short- ings empire. With the merger of fair amount of money, I stayed on for changed in the number of academic hours SunAmerica into AIG in 1999, a year or two and decided to focus they get a year compared with other nations. Broad stepped down as CEO and on public education as the biggest Second, we need to have the same competition turned his attention to full-time Eli Broad problem in America. I knew what was we have in higher education among private philanthropy. Eli and Edythe Broad happening in Korea, Japan, China, and public universities, and that can happen in had created a family foundation in the ’60s as India, and certain European nations and knew the form of charter schools, which are free, or a way to support their charitable interests and we had to improve public education. -

100823 Broad Collection Location Architect Announcement

news release Broad Collection to be Built on Grand Avenue in Downtown Los Angeles; Broads Name Diller Scofidio + Renfro as Architect For Immediate Release Contact: Karen Denne Monday, Aug. 23, 2010 310-954-5058 LOS ANGELES – The Broad Collection, a public museum of contemporary art and headquarters of The Broad Art Foundation’s worldwide lending library, will be built on Grand Avenue in downtown Los Angeles and will be designed by world-renowned architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro, philanthropists Eli and Edythe Broad announced today. With today’s approval by the Grand Avenue Authority, on the heels of unanimous support by the Los Angeles City Council and Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) and the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, the Broads have all the necessary approvals to build the approximately 120,000-square-foot museum. The Broads are expected to spend between $80 million and $100 million to build the museum and a parking garage, which was added to the project at the request of the CRA. They will also pay $7.7 million to lease the land, and they will endow The Broad Art Foundation with $200 million to cover ongoing annual operating expenses. The Broads’ decision comes after three years of evaluating locations in Beverly Hills, Santa Monica and Los Angeles. “Our heart is on Grand Avenue in downtown Los Angeles,” said Eli Broad. “This is our gift to the city that has been so good to us. We want to make great works of contemporary art accessible to the broadest public, and we can think of no better location than in the center of the contemporary art capital of the world. -

The Broad Foundations

The Broad Foundations The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and The Broad Art Foundation together comprise The Broad Foundations, which have assets of $2.7 billion and a combined mission of advancing entrepreneurship for the public good in education, science and the arts. The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation is a national venture philanthropy established by entrepreneur and philanthropist Eli Broad and his wife Edythe. As graduates of Detroit Public Schools, the Broads created The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, which seeks to ensure that every student in an urban public school has the opportunity to succeed. Bringing together top education experts and practitioners, the foundation funds system-wide programs and policies that strengthen public schools by creating environments that allow good teachers to do great work and enable students of all backgrounds to learn and thrive. The Broad Foundation’s major education initiatives include the $1 million Broad Prize for Urban Education, the largest education award in the country that recognizes the large urban school district making the greatest progress in America in raising student achievement, and The Broad Center, a nonprofit that seeks to prepare strong leaders of public school systems through its two initiatives, The Broad Academy and The Broad Residency in Urban Education. The Broad Foundation also invests in advancing innovative scientific and medical research in the areas of human genomics, stem cell research and inflammatory bowel disease. In an unprecedented partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University and its affiliated hospitals and the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, the Broads have committed $700 million to fund The Broad Institute, the world’s leading genomic medicine research institute that is focused on using the power of genomics to understand human disease. -

The Broad Foundations Thebroad Foundations

years 5 yea10rs science education years 25 2009|2010 the arts ENTREPRENEURSHIP FOR THE PUBLIC GOOD IN EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND THE ARTS THE BROAD FOUNDATIONS THEBROAD FOUNDATIONS The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation The Broad Art Foundation The Mission ofThe Broad Foundations Transforming K-12 urban public education through better governance, management, labor relations and competition Making significant contributions to advance major scientific and medical research Fostering public appreciation of contemporary art by increasing access for audiences worldwide Leading and contributing to major civic projects in Los Angeles TABLE OF C ONTENTS Letterfrom theDirectors 2 Education 8 Scientific | Medical Research 28 Arts, Culture and Civic Initiatives 54 Financial Statement 76 Board of Governors 77 TheBroad Team 78 LETTER FROMTHE DIRECTORS In some ways, it seems like we’ve spent a lifetime as philanthropists. 3 At other moments, this experience feels brand new. This year marks the fifth anniversary of the founding of the Broad Institute, the 10th anniversary of our entry into education reform, and the 25th anniversary of The Broad Art Foundation. Anniversaries or milestones, whatever you choose to call them, are significant. To us, they are a reason to pause and reflect on how far we’ve come, what we’ve accomplished, and what we have left to do. While it is often tempting to view milestones like these as a self- congratulatory exercise, we prefer to see them as an opportunity to turn a critical eye on our work. Yes, what have been our most successful investments, but also, what were the risks we took that didn’t pay off? What work do we still have to do? How has the landscape changed, how has our approach evolved, and what have we learned over these past five, 10, 25 years? Scientific and medical research is our newest area of philanthropy, but it is the one in which we have made the greatest progress in the short- est amount of time. -

TAM VAN TRAN Biography 1966 Born in Kontum, Vietnam Lives

TAM VAN TRAN Biography 1966 Born in Kontum, Vietnam Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA Education 1996 Graduate Film and Television Program, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 1990 BFA Painting, Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY Selected Awards 2008 California Community Foundation Fellowship Art Matters, Spring, Grantee 2001 Joan Mitchell Foundation Award 2000 Pollock Krasner Fellowship 1993 Ucross Artists Residency, Ucross, Wyoming 1991 Creative Fellowship in the Visual Arts, Colorado Council on the Arts and Humanities Solo Exhibitions 2018 Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA 2017 Black Melong, Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY 2015 Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA Tam Van Tran: Exodus, Susanne Vilmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA Aikido Dream, Museum of Contemporary Art, Santa Barbara, CA Breathing, Art Gallery, Long Beach City College, Long Beach, CA 2014 Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco, CA Susanne Vielmetter Projects, Los Angeles, CA Brand New Gallery, Milan, Italy 2013 Leaves of Ore, Ameringer / McEnery / Yohe, New York, NY Ceramic Leaves of Ore, solo booth with Ameringer / McEnery / Yohe at The Art Show, New York, NY 2012 San Art, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Adornment of Basic Space, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA 2010 MIND IS A PURE EXPANSE OF SPACE, Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco, CA 2008 Susanne Vielmetter, Los Angeles, CA Luminosity, Cohan and Leslie, New York, NY 2006 Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco,