An Ozdessey in Plato

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3495 N. Victoria, Shoreview, Mn 55126

3495 N. VICTORIA, SHOREVIEW, MN 55126 WWW.STODILIA.ORG FEBRUARY 26, 2017 * 8TH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME PRAYERS FOR THE SICK OUR PARISH COMMUNITY Jerry Ciresi, Doug Miller, Tiffany Pohl, Laure Waschbusch, Patricia Pfenning-Wendt, Jerry Bauer, Mary Ellen Suwan, NEW PARISHIONER BRIEFINGS & WELCOME Jim Andal, Lee & Virginia Johnson, Louise Simon, Michael Would you like to join the parish? Mrugala, Rosemary Vetsch, Agnes Walsh, Bertha Karth, The New Parishioner Briefings are: Zoey McDonald, Elizabeth Bonitz, Lorraine Kadlec, • Thurs., March 9 at 7:00pm in Rm.1302 • Elizabeth Waschbusch, Jim Czeck, Barbara Dostert, Steve Sun., March 19 after the 9:00am Mass in Rm. 1302 Pasell, Craig Monson, Colt Moore, Pat Keppers, Marian We will welcome new parishioners (who have already at- Portesan, Glenn Schlueter, Alan Kaeding, Helen and Lowell tended a briefing) at the 9:00am Mass and Reception next Carlen, Mary Donahue, Pat Kassekert, Bob Rupar, Emma Sunday, March 5, 2017. Please give them a warm wel- Tosney, Bernadette Valento, Philippa Lindquist, Trevor come! Pictures of our new members are posted on the par- Ruiz, Steve Lauinger, Linda Molenda, Michael Carroll, John ish bulletin board in the school hallway. Gravelle, Lynn Latterell, Harry Mueller, Haley Crain, Joan SOCIAL JUSTICE CORNER Rourke, Mary Lakeman, John Lee, Romain Hamernick, The Dignity of each Person - “What did you call me?” Marlene Dirkes, Clementine Brown, Lynn Schmidt, Donna by Hosffman Ospino, Assistant Professor of Hispanic Ministry and Heins, Kelly & Emilia Stein, Bob Zermeno, Joan Kurkowski, Religious Education, Boston College School of Theology Educa- Joan Kelly, Erin Joseph, Patricia Wright. Help us keep this tion. -

Abducted to Oz, He Had Considered It His Mission to Get Home Again

CHAPTER ONE: THE ABDUCTION The boy was doing his homework. His parents had taken his little brother to see Return to Oz at the movie theater. He had seen it when it first came out and, although he enjoyed it at the time, he felt he was getting too old for that sort of stuff. Besides, he had too much work to do. It seemed to him that each teacher allocated enough work to practically take up a fellow's entire evening—as if their class was the only one. So Graham, for that was his name, knew he would have to work for several more hours if he was to complete all the assignments. Graham began to work on his math problems, but he could not concentrate. His mind drifted off to the original L. Frank Baum story: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. He was thinking about the characters in it and what a terrific imagination Mr. Baum must have had, when suddenly, out of the stillness of the house, came a weird screeching sound. The sound was like nothing he had ever heard before. It seemed to have come from behind him; from the vicinity of the fireplace. Graham shivered. He did not believe in ghosts, and at twelve years old (almost thirteen) he should not be afraid to be home alone. But he was scared right now —no question about it. However, when no other sound was forthcoming, he began to rationalize that it had all been his imagination, perhaps just the wind whistling down the chimney. -

Oz: a Reflection of America

Allen 1 Monica Allen 11 March 2015 Oz: A Reflection of America L. Frank Baum said that his book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is meant to be a “modernized fairy tale” (3), or, in other words, an American fairy tale, the first of its kind, and he certainly did succeed. The Wizard of Oz has found its way into the homes of every American from the actual book to the movie to Oz episodes and arcs on TV. Dorothy is one of the most, if not the most, recognizable American figures. Henry Littlefield once said that The Wizard of Oz has “unsuspected depth” and that “Baum’s immortal American fantasy encompasses more than heretofore believed” (50). Littlefield is talking about how he believes Baum wrote The Wizard of Oz to be a “parable on populism” (47), but that allegory has no place in modern society. As Gretchen Ritter puts so elegantly, “Americans today dimly recollect the Populists as farmers in search of better prices for their crops” (174), most Americans do not have this problem today and will, most likely, never have this problem again. Therefore, Littlefield’s “parable on populism” (47), while an interesting read, is no longer that applicable. Instead, one should focus on the total “American-ness” of the first American fairy tale. Other fairy tales can reflect what their home country was like and this one does as well. Jerry Griswold states “what can’t be ignored is how much the Land of Oz is a reflection of actual circumstances [in America] at the turn of the century” (463). -

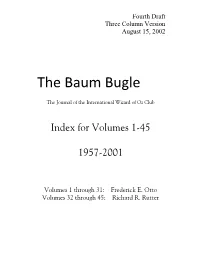

The Baum Bugle

Fourth Draft Three Column Version August 15, 2002 The Baum Bugle The Journal of the International Wizard of Oz Club Index for Volumes 1-45 1957-2001 Volumes 1 through 31: Frederick E. Otto Volumes 32 through 45: Richard R. Rutter Dedications The Baum Bugle’s editors for giving Oz fans insights into the wonderful world of Oz. Fred E. Otto [1927-95] for launching the indexing project. Peter E. Hanff for his assistance and encouragement during the creation of this third edition of The Baum Bugle Index (1957-2001). Fred M. Meyer, my mentor during more than a quarter century in Oz. Introduction Founded in 1957 by Justin G. Schiller, The International Wizard of Oz Club brings together thousands of diverse individuals interested in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and this classic’s author, L. Frank Baum. The forty-four volumes of The Baum Bugle to-date play an important rôle for the club and its members. Despite the general excellence of the journal, the lack of annual or cumulative indices, was soon recognized as a hindrance by those pursuing research related to The Wizard of Oz. The late Fred E. Otto (1925-1994) accepted the challenge of creating a Bugle index proposed by Jerry Tobias. With the assistance of Patrick Maund, Peter E. Hanff, and Karin Eads, Fred completed a first edition which included volumes 1 through 28 (1957-1984). A much improved second edition, embracing all issues through 1988, was published by Fred Otto with the assistance of Douglas G. Greene, Patrick Maund, Gregory McKean, and Peter E. -

The Politics of Oz: a Symposium

Copyright © 2001 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. The Politics of O2: A Symposium Micbael Gessel, Nancy Tystad Koupal, and Fred Erisman The following papers were originally presented at die Oz Cen- tenniid, 1900-2000, conlerence in Bloomington, Indiana, on 21 July 2000. In response to the popular theory that The Wizard qfOz is an allegorical tribute to the Populist movement of the 1890s. the panel considered the question: "Was L. Frank Baum a Populist Sympa- thizer?" To address the problem, three aspects needed consider- ation: where did the idea originate and how did it grow? what did the historical record show? and was diere a political mading of die book diat was more in keeping with Baum's politics and the his- tory of the period? The Wizard ofOzzs Urban Legend Michael Gessel "Whether they have seen the movie or read the book, most American children love The Wizard ofOz as much today as when L. Frank Baum wrote it in 1900. Few realize, though, diat the story is an allegory. Beneath the fantasy of Dorodiy in the land of the Munchkins, Baum was writing about the problems of farmers and industrial workers," This explanation of America's most popular diild- ren's book came from Why We Remember, a 1988 history textbook Copyright © 2001 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. Summer2001 Politics of Oz 147 for grades six through nine.' "The story of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz' was written solely to pleasure children of today." Tliat contra- dictory statement was otfered by no less tlian die autiior liimseir, L. -

DAMMIT, TOTO, WE're STILL in KANSAS: the FALLACY of FEMINIST EVOLUTION in a MODERN AMERICAN FAIRY TALE by Beth Boswell a Diss

DAMMIT, TOTO, WE’RE STILL IN KANSAS: THE FALLACY OF FEMINIST EVOLUTION IN A MODERN AMERICAN FAIRY TALE by Beth Boswell A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University May 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Martha Hixon, Director Dr. Will Brantley Dr. Jane Marcellus This dissertation is dedicated, in loving memory, to two dearly departed souls: to Dr. David L. Lavery, the first director of this project and a constant voice of encouragement in my studies, whose absence will never be wholly realized because of the thousands of lives he touched with his spirit, enthusiasm, and scholarship. I am eternally grateful for our time together. And to my beautiful grandmother, Fay M. Rhodes, who first introduced me to the yellow brick road and took me on her back to a pear-tree Emerald City one hundred times or more. I miss you more than Dorothy missed Kansas. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the educators who have pushed me to challenge myself, to question everything in the world around me, and to be unashamed to explore what I “thought” I already knew, over and over again. Though there are too many to list by name, know that I am forever grateful for your encouragement and dedication to learning, whether in the classroom or the world. I would like to thank my phenomenal committee for their tireless support and assistance in this project. I am especially grateful for Dr. Martha Hixon, who stepped in as my director after the passing of Dr. -

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Teaching Unit

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Interactive Reader Quick and Dirty Teaching Guide with Student Sample Answers The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Written by by L. Frank Baum 1 Chapter 1 Teaching It! Chapter 1 of The Wizard of Oz begins the tale of a orphaned girl from Kansas who gets swept away from her dull, gray life by a cyclone. The descriptions in this chapter are bleak and as gray as the storm itself. “Sun‐baked”, gray and an uncle who never laughs are examples of the heavy and solitary life Dorothy lives. Discussion Question: Can you imagine a parent in your house covering her ears when you laugh. Give students a moment to discuss this together. When Baum published The Wizard of Oz in 1900, some speculated that it was an allegory for the Industrial Revolution and capitalism. Others say it is just a great fairy tale for children. Baum uses color throughout the book. When you discuss the symbolism of color, it is helpful to poll your students to ask who has seen the original movie and discuss how the Kansas scene at the opening of the movie is black and white but when Dorothy lands in Oz, it is in Technicolor. Chapter 2 Teaching It! Chapter 2 of The Wizard of Oz opens in brilliantly bright colors. The sun is shining. The stormy skies of Kansas have figuratively and literally opened up to an adventure. The Munchkins wear blue, the Wicked Witches shoes are silver and the road is paved in bright yellow bricks! Even the home of the Great Wizard is a color – Emerald. -

Systemic Oppression in Children's Portal-Quest

Systemic Oppression in Children’s Portal-Quest Fantasy Literature by Christopher Owen B.A. (Hons), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Children's Literature) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2015 © Christopher Owen, 2015 Abstract This thesis investigates the representation of systemic oppression in Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. Employing Foucauldian poststructuralism and critical discourse analysis, this research identifies how the social systems of the fantasy texts construct hierarchies based on race and gender, and social norms based on sexuality and disability. Privilege and oppression are identified as the results of the relaying of power relations by social institutions through strategies such as dominant discourses. This study questions the historically understood role of children’s and fantasy literature as socialization tools, and the potential negative consequences of this. ii Preface This Master of Arts thesis is an original, unpublished, independent work of the author, Christopher Owen, as a partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts in Children’s Literature Program at the University of British Columbia. Dr. Eric Meyers of the University of British Columbia’s School of Library, Archival and Information Studies supervised the writing of this thesis. Drs. Theresa Rogers and Rick Gooding, of the Language and Literacy Education and English Departments at the University of British Columbia respectively, acted as second readers. I will present portions of this research at the International Research Society in Children’s Literature 22nd Biennial Congress, “Creating Childhoods” at the University of Worcester, in the United Kingdom in August 2015. -

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Study Guide

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Study Guide Objectives The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is an entertaining and educational epic production that facilitates learning across all age groups. This study guide is an aid for parents and teachers to help children gain important and relevant knowledge of our adaptation, theatre etiquette, performing arts and puppetry. Included are applicable South Carolina standards, a synopsis of the show, types of puppetry used and discussion topics for before and after the show. South Carolina Educational Standards Kindergarten - 8th Grade: Visual and Performing Arts TK-T1-7.3 Describe emotions evoked by theatre experiences. TK-T8-7.1 Identify audience etiquette to be used during theatre activities and performances. TK-T3-6.1 Compare and contrast theatre activities and experiences with those encountered in other disciplines. TK-T5-8.2 Experience live or recorded theatre performances. T1-T5-6.4 Use theatrical conventions (for example, puppets, masks, props) in theatre activities. T1&T2-7.2 Describe the characters, setting, events, and technical elements of a particular theatrical experience. T3-T5-7.2 & T6-7.3 Give oral and written responses to live and recorded theatre performances. T4-T8-5.3 Research information about various careers in theatre. T4-T5-6.1 Demonstrate the understanding that theatre incorporates all arts areas. T6-8.2 & T7-8.3 Recognize ways that live and recorded theatre relates to real life. Kindergarden-8th grade: English Language Arts RL Standard 6: Summarize key details and ideas to support analysis of thematic development. RL Standard 7: Analyze the relationship among ideas, themes, or topics in multiple media, formats, and in visual, auditory, and kinesthetic modalities. -

A Commentary on the Erasure of Matilda Joslyn Gage

NO WITCH IS A BAD WITCH: A COMMENTARY ON THE ERASURE OF MATILDA JOSLYN GAGE ZANITA E. FENTON* I. INTRODUCTION There is something unreal about living in a world replete with borders, bias, and a seemingly infinite range of inequality. Where do Truth, Rationality, Equality, and Justice reside? Is there a Land of Oz1 where this is true? Can our imaginations create the reality to which we aspire? Will this place ever be Home? I wonder if I will ever find it or if it is only fantasy. Someone clearly forgot to give me my silver shoes.2 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, by L. Frank Baum, is an enduring children‘s story, notable for its progressive messages.3 The most obvious of these include the release of the munchkins4 in a post-abolitionist society5 * Professor of Law, University of Miami School of Law. I dedicate this Essay to my sister, Deidra Fenton Mahoney (1962–2010), with whom I spent many hours watching The Wizard of Oz and The Wiz. I thank all the participants of the Taking Oz Seriously symposium for comment and camaraderie that made writing this essay possible. I appreciate Charlton Copeland, Caroline Corbin, Mary Anne Franks and Margaret Sachs for their insightful comments and feedback during the writing process. I thank 1librarian, Pam Lucken, for her exceptional research skill. See generally L. FRANK BAUM, THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ (2003) (creating a fantasy world— called the Land of Oz). This book was originally published in 1900 and was the first in the ―Oz‖ series 2of fifteen books written by Baum. -

The Symbolical World of the Wonderful Wizard of Oz

The Symbolical World of the Wonderful Wizard of Oz Hercigonja, Ines Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Pula / Sveučilište Jurja Dobrile u Puli Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:137:546932 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-06 Repository / Repozitorij: Digital Repository Juraj Dobrila University of Pula Sveučilište Jurja Dobrile u Puli Fakultet za odgojne i obrazovne znanosti INES HERCIGONJA THE SYMBOLICAL WORLD OF THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ Diplomski rad Pula, 2020 Sveučilište Jurja Dobrile u Puli Fakultet za odgojne i obrazovne znanosti INES HERCIGONJA THE SYMBOLICAL WORLD OF THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ Diplomski rad JMBAG: 0117212872, redoviti student Studijski smjer: Integrirani preddiplomski I diplomski sveučilišni učiteljski studij Predmet: Dječja književnost na engleskom jeziku 3 Znanstveno područje: Humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: Književnost Znanstvena grana: Filologija Mentor: izv. prof.dr. sc. Igor Grbić Pula, rujan 2020. IZJAVA O AKADEMSKOJ ČESTITOSTI Ja, dolje potpisani Ines Hercigonja, kandidat za prvostupnika magistra primarnog obrazovanja ovime izjavljujem da je ovaj Završni rad rezultat isključivo mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na objavljenu literaturu kao što to pokazuju korištene bilješke i bibliografija. Izjavljujem da niti jedan dio Završnog rada nije napisan na nedozvoljen način, odnosno da je prepisan iz kojega -

The Old Mill Times

The Old Mill Times Patron: Garry Lawrence All the news and views from the Online bookings: oldmilltheatre.com.au/tickets Old Mill Theatre for JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2017 Plus-sized laughs in play that brings home the bacon AN AWARD-winning comedy that takes a politically incor- rect look at our obsession with appearance is the Old Mill Theatre’s first season of 2017. Written by Neil LaBute and directed by Les Hart, Fat Pig focuses on a good-looking young man who becomes involved with a plus-sized librarian. When Tom falls in love with Helen, he is ecstatic – but is conflicted when his work colleague is highly insulting about the relationship due to Helen’s weight and appearance. The play follows Tom and Helen’s journey through a poignant and eye-opening production that hits on the topics of outside influences on decision-making and the human tendency to choose beauty over substance. Winning the Outer Critics Circle Award for Outstanding Off- Broadway Play, LaBute was inspired to write Fat Pig after an experiment with dieting – as his weight decreased so did his focus on writing. Les said the play will challenge audiences about some of their prejudices. “In this case, the focus is on size but it could just as effectively Briana Dunn is appearing as the librarian Helen in Fat Pig, a play that looks at our obsession with appearance. tackle sexuality, religion or colour,” he said. “Of course, the title would need to be changed for those. “But it really is about moving past that first impression and getting to know the individual.