Phosphate in Virulence of Candida Albicans and Candida Glabrata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Materials

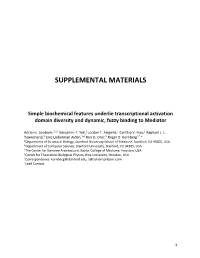

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS Simple biochemical features underlie transcriptional activation domain diversity and dynamic, fuzzy binding to Mediator Adrian L. Sanborn,1,2,* Benjamin T. Yeh,2 Jordan T. Feigerle,1 Cynthia V. Hao,1 Raphael J. L. Townshend,2 Erez Lieberman Aiden,3,4 Ron O. Dror,2 Roger D. Kornberg1,*,+ 1Department of Structural Biology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 2Department of Computer Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 3The Center for Genome Architecture, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, USA 4Center for Theoretical Biological Physics, Rice University, Houston, USA *Correspondence: [email protected], [email protected] +Lead Contact 1 A B Empty GFP Count Count Count VP16 AD mCherry mCherry GFP C G Count 2 AD tiles 10 Random sequences 2 12 10 10 Gcn4 AD 8 1 10 1 6 10 Z-score Activation 4 Count 2 0 Activation, second library 0 10 0 10 Gal4 Gln3 Hap4 Ino2 Ino2 Msn2 Oaf1 Pip2 VP16 VP64 r = 0.952 Pho4 AD 147 104 112 1 108 234 995 944 0 1 2 Synonymously encoded control ADs 10 10 10 Activation, first library Count H 102 GFP 101 D E Empty VP16 activation 100 80% Mean positional VP16 AD 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 60% Position in Adr1 protein 40% By FACS GFP By sequencing I 20% 50% 0% Percent of cells 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 mCherry mCherry 25% 80% Gcn4 AD 60% Empty VP16 0% 40% AD at position with Percent of proteins 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 20% Position on protein, normalized 0% Percent of cells 100% 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 100% 80% 75% 75% Pho4 AD / mCherry ratio GFP 60% GFP GFP 50% 50% 40% 20% 25% 25% C-term ADs 0% ADs Percent of Percent of cells Other ADs 0% 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 0% 1 2 F 25 50 75 100 125 10 10 Gcn4 hydrophobic mutants (cumulative distribution) GFP bin number 1 AD length Activation J 1.0 0 0.8 0.6 0.4 −1 (log2 change vs wild-type) 0.2 Frequency of aTF expression 5 10 15 TFs without ADs falling within sorted mCh range Hydrophobic content 0.0 TFs with ADs Cumulative fraction of TFs (kcal/mol) 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 Fraction of genes regulated by TF that are activating Figure S1. -

Regulation of Components of the Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Phosphate-Starvation-Inducible Regulon in Escherichia Coii

Molecular Microbiology (1988) 2(3), 347-352 Regulation of components of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa phosphate-starvation-inducible regulon in Escherichia coii R. J. Siehnel, E. A. Worobec and R. E. W. Hancock* of the structural elements of the Pho regulon since, in such Department ot Microbioiogy, University ot British mutants, another regulatory gene product, PhoM, will tran- Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada scriptionally activate PhoB. The PhoM activator is not con- V6T1W5. trolled by changes in phosphate levels and is repressed when PhoR is functional. Summary Conditions of low environmental phosphate stimulate the co-induction, in E. coli, of an outer membrane porin Plasmids pPBP and pRS-XP containing the cloned (PhoE), a periplasmic phosphate-binding protein (PhoS), genes for the Pseudomonas aeruginosa phosphate- and a periplasmic alkaline phosphatase (PhoA). JUephoB starvation-inducible periplasmic phosphate-binding gene product appears to activate the transcription of each protein and outer membrane porin P {oprP), respec- of these genes by interacting with specific regulation tively, were introduced into various Escherichia coti sequences located in analogous regions upstream from Pho-regulon regulatory mutants. Using Western the structural genes. These sequences are highly hom- immunoblots and specific antisera, the production of ologous and have been termed the 'Pho box' (Shinagawa both gene products was observed to be under the etai., 1987). control of regulatory elements of the E. coti Pho regu- Phosphate transport has been examined in several other lon. Sequencing of the region upstream of the trans- bacterial species and recent evidence suggests that a lationai start site of the oprP gene revealed a 'Pho phosphate-starvation-inducible regulon, similar to that box' with strong homology to the E. -

Chromatin Dynamics in The

TRANSCRIPTION AND CHROMATIN DYNAMICS IN THE NOTCH SIGNALLING RESPONSE Zoe Pillidge Churchill College Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 TRANSCRIPTION AND CHROMATIN DYNAMICS IN THE NOTCH SIGNALLING RESPONSE During normal development, different genes are expressed in different cell types, often directed by cell signalling pathways and the pre-existing chromatin environment. The highly-conserved Notch signalling pathway is involved in many cell fate decisions during development, activating different target genes in different contexts. Upon ligand binding, the Notch receptor itself is cleaved, allowing the intracellular domain to travel to the nucleus and activate gene expression with the transcription factor known as Suppressor of Hairless (Su(H)) in Drosophila melanogaster. It is remarkable how, with such simplicity, the pathway can have such diverse outcomes while retaining precision, speed and robustness in the transcriptional response. The primary goal of this PhD has been to gain a better understanding of this process of rapid transcriptional activation in the context of the chromatin environment. To learn about the dynamics of the Notch transcriptional response, a live imaging approach was used in Drosophila Kc167 cells to visualise the transcription of a Notch-responsive gene in real time. With this technique, it was found that Notch receptor cleavage and trafficking can take place within 15 minutes to activate target gene expression, but that a ligand-receptor interaction between neighbouring cells may take longer. These experiments provide new data about the dynamics of the Notch response which could not be obtained with static time-point experiments. -

Intrinsic Specificity of DNA Binding and Function of Class II Bhlh

INTRINSIC SPECIFICITY OF BINDING AND REGULATORY FUNCTION OF CLASS II BHLH TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE Jane E. Johnson Ph.D. Helmut Kramer Ph.D. Genevieve Konopka Ph.D. Raymond MacDonald Ph.D. INTRINSIC SPECIFICITY OF BINDING AND REGULATORY FUNCTION OF CLASS II BHLH TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS by BRADFORD HARRIS CASEY DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Dallas, Texas December, 2016 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family, who have taught me pursue truth in all forms. To my grandparents for inspiring my curiosity, my parents for teaching me the value of a life in the service of others, my sisters for reminding me of the importance of patience, and to Rachel, who is both “the beautiful one”, and “the smart one”, and insists that I am clever and beautiful, too. Copyright by Bradford Harris Casey, 2016 All Rights Reserved INTRINSIC SPECIFICITY OF BINDING AND REGULATORY FUNCTION OF CLASS II BHLH TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS Publication No. Bradford Harris Casey The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, 2016 Jane E. Johnson, Ph.D. PREFACE Embryonic development begins with a single cell, and gives rise to the many diverse cells which comprise the complex structures of the adult animal. Distinct cell fates require precise regulation to develop and maintain their functional characteristics. Transcription factors provide a mechanism to select tissue-specific programs of gene expression from the shared genome. -

Phosphate Uptake by the Phosphonate Transport System Phncde Raffaele Stasi†, Henrique Iglesias Neves† and Beny Spira*

Stasi et al. BMC Microbiology (2019) 19:79 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1445-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Phosphate uptake by the phosphonate transport system PhnCDE Raffaele Stasi†, Henrique Iglesias Neves† and Beny Spira* Abstract Background: Phosphate is a fundamental nutrient for all creatures. It is thus not surprising that a single bacterium carries different transport systems for this molecule, each usually operating under different environmental conditions. The phosphonate transport system of E. coli K-12 is cryptic due to an 8 bp insertion in the phnE ORF. Results: Here we report that an E. coli K-12 strain carrying the triple knockout pitA pst ugp reverted the phnE mutation when plated on complex medium containing phosphate as the main phosphorus source. It is also shown that PhnCDE takes up orthophosphate with transport kinetics compatible with that of the canonical transport system PitA and that Pi-uptake via PhnCDE is sufficient to enable bacterial growth. Ugp, a glycerol phosphate transporter, is unable to take up phosphate. Conclusions: The phosphonate transport system, which is normally cryptic in E. coli laboratory strains is activated upon selection in rich medium and takes up orthophosphate in the absence of the two canonical phosphate-uptake systems. Based on these findings, the PhnCDE system can be considered a genuine phosphate transport system. Keywords: Phosphonates, Phosphate, Phn, PHO regulon Background phosphatase (AP). Genes belonging to the PHO regu- Phosphorus is a macronutrient of utmost importance to lon are synchronously induced by Pi-shortage [2]. For the all living beings. It is thus not surprising that bacte- sake of simplicity, the operons pstSCAB-phoU, ugpBAEC, ria developed several different mechanisms of phospho- phnCDEFGHIJKLMNOP will be respectively shortened to rus acquisition. -

An Activation-Specific Role for Transcription Factor TFIIB in Vivo (Sua7͞pho4͞pho5͞transcriptional Control)

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 96, pp. 2764–2769, March 1999 Biochemistry An activation-specific role for transcription factor TFIIB in vivo (SUA7yPho4yPHO5ytranscriptional control) WEI-HUA WU AND MICHAEL HAMPSEY* Department of Biochemistry, Division of Nucleic Acids Enzymology, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, 675 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854-5635 Edited by Robert G. Roeder, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, and approved January 20, 1999 (received for review November 9, 1998) ABSTRACT A yeast mutant was isolated encoding a sin- a study of PIC formation and transcriptional activity demon- gle amino acid substitution [serine-53 3 proline (S53P)] in strated that PIC assembly occurs by at least two steps and that transcription factor TFIIB that impairs activation of the the TATA box and TFIIB also can affect transcription subse- PHO5 gene in response to phosphate starvation. This effect is quent to PIC assembly (11). Thus, processes other than factor activation-specific because S53P did not affect the uninduced recruitment are potential activator targets. level of PHO5 expression, yet is not specific to PHO5 because TFIIB is recruited to the PIC by the acidic activator VP16 Adr1-mediated activation of the ADH2 gene also was impaired and the proline-rich activator CTF1 (3, 12). VP16 directly by S53P. Pho4, the principal activator of PHO5, directly targets TFIIB (3) and this interaction is required for activation interacted with TFIIB in vitro, and this interaction was (13, 14). Interestingly, VP16 induces a conformational change impaired by the S53P replacement. Furthermore, Pho4 in- in TFIIB that disrupts the intramolecular interaction between duced a conformational change in TFIIB, detected by en- the N- and C-terminal domains in solution (15). -

The HLH-6 Transcription Factor Regulates C

The HLH-6 Transcription Factor Regulates C. elegans Pharyngeal Gland Development and Function Ryan B. Smit1, Ralf Schnabel2, Jeb Gaudet1,3* 1 Genes and Development Research Group, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, 2 Institut fu¨r Genetik, Technische Universita¨t Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany, 3 Department of Medical Genetics, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada Abstract The Caenorhabditis elegans pharynx (or foregut) functions as a pump that draws in food (bacteria) from the environment. While the ‘‘organ identity factor’’ PHA-4 is critical for formation of the C. elegans pharynx as a whole, little is known about the specification of distinct cell types within the pharynx. Here, we use a combination of bioinformatics, molecular biology, and genetics to identify a helix-loop-helix transcription factor (HLH-6) as a critical regulator of pharyngeal gland development. HLH-6 is required for expression of a number of gland-specific genes, acting through a discrete cis-regulatory element named PGM1 (Pharyngeal Gland Motif 1). hlh-6 mutants exhibit a frequent loss of a subset of glands, while the remaining glands have impaired activity, indicating a role for hlh-6 in both gland development and function. Interestingly, hlh-6 mutants are also feeding defective, ascribing a biological function for the glands. Pharyngeal pumping in hlh-6 mutants is normal, but hlh-6 mutants lack expression of a class of mucin-related proteins that are normally secreted by pharyngeal glands and line the pharyngeal cuticle. An interesting possibility is that one function of pharyngeal glands is to secrete a pharyngeal lining that ensures efficient transport of food along the pharyngeal lumen. -

25 Chrysosporium

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universidade do Minho: RepositoriUM 25 Chrysosporium Dongyou Liu and R.R.M. Paterson contents 25.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 197 25.1.1 Classification and Morphology ............................................................................................................................ 197 25.1.2 Clinical Features .................................................................................................................................................. 198 25.1.3 Diagnosis ............................................................................................................................................................. 199 25.2 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................................... 199 25.2.1 Sample Preparation .............................................................................................................................................. 199 25.2.2 Detection Procedures ........................................................................................................................................... 199 25.3 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................................................................200 -

From Prokaryotic to Eukaryotic Cells

This is a repository copy of Pi sensing and signaling: from prokaryotic to eukaryotic cells. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/95967/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Wanjun, QI, Baldwin, SA, Muench, SP orcid.org/0000-0001-6869-4414 et al. (1 more author) (2016) Pi sensing and signaling: from prokaryotic to eukaryotic cells. Biochemical Society Transactions, 44 (3). pp. 766-773. ISSN 0300-5127 https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20160026 © 2016, The Author(s). Published by Portland Press Limited on behalf of the Biochemical Society. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Biochemical Society Transactions. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal -

Culture Inventory

For queries, contact the SFA leader: John Dunbar - [email protected] Fungal collection Putative ID Count Ascomycota Incertae sedis 4 Ascomycota Incertae sedis 3 Pseudogymnoascus 1 Basidiomycota Incertae sedis 1 Basidiomycota Incertae sedis 1 Capnodiales 29 Cladosporium 27 Mycosphaerella 1 Penidiella 1 Chaetothyriales 2 Exophiala 2 Coniochaetales 75 Coniochaeta 56 Lecythophora 19 Diaporthales 1 Prosthecium sp 1 Dothideales 16 Aureobasidium 16 Dothideomycetes incertae sedis 3 Dothideomycetes incertae sedis 3 Entylomatales 1 Entyloma 1 Eurotiales 393 Arthrinium 2 Aspergillus 172 Eladia 2 Emericella 5 Eurotiales 2 Neosartorya 1 Paecilomyces 13 Penicillium 176 Talaromyces 16 Thermomyces 4 Exobasidiomycetes incertae sedis 7 Tilletiopsis 7 Filobasidiales 53 Cryptococcus 53 Fungi incertae sedis 13 Fungi incertae sedis 12 Veroneae 1 Glomerellales 1 Glomerella 1 Helotiales 34 Geomyces 32 Helotiales 1 Phialocephala 1 Hypocreales 338 Acremonium 20 Bionectria 15 Cosmospora 1 Cylindrocarpon 2 Fusarium 45 Gibberella 1 Hypocrea 12 Ilyonectria 13 Lecanicillium 5 Myrothecium 9 Nectria 1 Pochonia 29 Purpureocillium 3 Sporothrix 1 Stachybotrys 3 Stanjemonium 2 Tolypocladium 1 Tolypocladium 2 Trichocladium 2 Trichoderma 171 Incertae sedis 20 Oidiodendron 20 Mortierellales 97 Massarineae 2 Mortierella 92 Mortierellales 3 Mortiererallales 2 Mortierella 2 Mucorales 109 Absidia 4 Backusella 1 Gongronella 1 Mucor 25 RhiZopus 13 Umbelopsis 60 Zygorhynchus 5 Myrmecridium 2 Myrmecridium 2 Onygenales 4 Auxarthron 3 Myceliophthora 1 Pezizales 2 PeZiZales 1 TerfeZia 1 -

Chrysosporium Keratinophilum IFM 55160 (AB361656)Biorxiv Preprint 99 Aphanoascus Terreus CBS 504.63 (AJ439443) Doi

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/591503; this version posted April 4, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Characterization of novel Chrysosporium morrisgordonii sp. nov., from bat white-nose syndrome (WNS) affected mines, northeastern United States Tao Zhang1, 2, Ping Ren1, 3, XiaoJiang Li1, Sudha Chaturvedi1, 4*, and Vishnu Chaturvedi1, 4* 1Mycology Laboratory, Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York, USA 2 Institute of Medicinal Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100050, PR China 3Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA 4Department of Biomedical Sciences, School of Public Health, University at Albany, Albany, New York, USA *Corresponding authors: Sudha Chaturvedi, [email protected]; Vishnu Chaturvedi, [email protected]. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/591503; this version posted April 4, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Psychrotolerant hyphomycetes including unrecognized taxon are commonly found in bat hibernation sites in Upstate New York. During a mycobiome survey, a new fungal species, Chrysosporium morrisgordonii sp. nov., was isolated from bat White-nose syndrome (WNS) afflicted Graphite mine in Warren County, New York. This taxon was distinguished by its ability to grow at low temperature spectra from 6°C to 25°C. Conidia were tuberculate and thick-walled, globose to subglobose, unicellular, 3.5-4.6 µm ×3.5-4.6 µm, sessile or borne on narrow stalks. -

Highlighting the Potential Utility of MBP Crystallization Chaperone For

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Highlighting the potential utility of MBP crystallization chaperone for Arabidopsis BIL1/BZR1 transcription factor‑DNA complex Shohei Nosaki1, Tohru Terada2, Akira Nakamura1, Kei Hirabayashi1, Yuqun Xu1, Thi Bao Chau Bui1, Takeshi Nakano3,4, Masaru Tanokura1* & Takuya Miyakawa1* The maltose‑binding protein (MBP) fusion tag is one of the most commonly utilized crystallization chaperones for proteins of interest. Recently, this MBP‑mediated crystallization technique was adapted to Arabidopsis thaliana (At) BRZ‑INSENSITIVE‑LONG (BIL1)/BRASSINAZOLE‑RESISTANT (BZR1), a member of the plant‑specifc BZR TFs, and revealed the frst structure of AtBIL1/BZR1 in complex with target DNA. However, it is unclear how the fused MBP afects the structural features of the AtBIL1/BZR1‑DNA complex. In the present study, we highlight the potential utility of the MBP crystallization chaperone by comparing it with the crystallization of unfused AtBIL1/BZR1 in complex with DNA. Furthermore, we assessed the validity of the MBP‑fused AtBIL1/BZR1‑DNA structure by performing detailed dissection of crystal packings and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with the removal of the MBP chaperone. Our MD simulations defne the structural basis underlying the AtBIL1/ BZR1‑DNA assembly and DNA binding specifcity by AtBIL1/BZR1. The methodology employed in this study, the combination of MBP‑mediated crystallization and MD simulation, demonstrates promising capabilities in deciphering the protein‑DNA recognition code. Maltose-binding protein (MBP) is the most useful and successful crystallization chaperone for challeng- ing proteins1–4, as MBP maintains the solubility of fusion proteins and is used as an afnity tag for protein purifcation5–8.