DAVID SURMAN Animated Caricature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

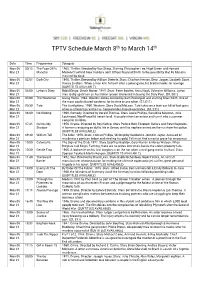

TPTV Schedule March 8Th to March 14Th

th th TPTV Schedule March 8 to March 14 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 08 00:15 The Face Of Fu 1965. Thriller. Directed by Don Sharp. Starring Christopher Lee, Nigel Green and Howard Mar 21 Manchu Marion-Crawford. New murders alert Officer Nayland Smith to the possibility that Fu Manchu may not be dead. Mon 08 02:05 Dark City 1950. Thriller. Directed by William Dieterle. Stars: Charlton Heston, Dean Jagger, Lizabeth Scott, Mar 21 Viveca Lindfors. When a man kills himself after a poker game, his brother looks for revenge. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 08 04:00 Lytton's Diary Rabid Dingo: Shock Horror. 1985. Stars: Peter Bowles, Anna Nygh, Sylvester Williams. Lytton Mar 21 tries to dig up dirt on an Australian tycoon interested in buying the Daily Post. (S1, E01) Mon 08 05:00 The Westerner Going Home. 1962. Western Series created by Sam Peckinpah and starring Brian Keith. One of Mar 21 the most sophisticated westerns for its time or any other. (S1, E11) Mon 08 05:30 Tate The Gunfighters. 1960. Western. Stars David McLean. Tate takes on a train car full of fast guns Mar 21 when a simmering rancher vs. homesteader dispute escalates. (S1, E11) Mon 08 06:00 No Kidding 1960. Comedy. Directed by Gerald Thomas. Stars Leslie Phillips, Geraldine Mcewan, Julia Mar 21 Lockwood, Noel Purcell & Irene Handl. A couple inherit an estate and turn it into a summer camp for children. Mon 08 07:45 Guilt Is My 1950. Drama. Directed by Roy Kellino. Stars Patrick Holt, Elizabeth Sellars and Peter Reynolds. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

|||GET||| Superheroes and American Self Image 1St Edition

SUPERHEROES AND AMERICAN SELF IMAGE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Michael Goodrum | 9781317048404 | | | | | Art Spiegelman: golden age superheroes were shaped by the rise of fascism International fascism again looms large how quickly we humans forget — study these golden age Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition hard, boys and girls! Retrieved June 20, Justice Society of America vol. Wonder Comics 1. One of the ways they showed their disdain was through mass comic burnings, which Hajdu discusses Alysia Yeoha supporting character created by writer Gail Simone for the Batgirl ongoing series published by DC Comics, received substantial media attention in for being the first major transgender character written in a contemporary context in a mainstream American comic book. These sound effects, on page and screen alike, are unmistakable: splash art of brightly-colored, enormous block letters that practically shout to the audience for attention. World's Fair Comics 1. For example, Black Panther, first introduced inspent years as a recurring hero in Fantastic Four Goodrum ; Howe Achilles Warkiller. The dark Skull Man manga would later get a television adaptation and underwent drastic changes. The Senate committee had comic writers panicking. Howe, Marvel Comics Kurt BusiekMark Bagley. During this era DC introduced the Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition of Batwoman inSupergirlMiss Arrowetteand Bat-Girl ; all female derivatives of established male superheroes. By format Comic books Comic strips Manga magazines Webcomics. The Greatest American Hero. Seme and uke. Len StrazewskiMike Parobeck. This era saw the debut of one of the earliest female superheroes, writer-artist Fletcher Hanks 's character Fantomahan ageless ancient Egyptian woman in the modern day who could transform into a skull-faced creature with superpowers to fight evil; she debuted in Fiction House 's Jungle Comic 2 Feb. -

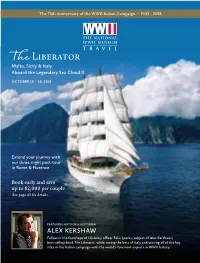

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

Chapter 3 Heroines in a Time of War: Nelvana of the Northern Lights And

Chapter 3 Heroines in a Time of War: Nelvana of the Northern Lights and Wonder Woman as Symbols of the United States and Canada Scores of superheroes emerged in comic books just in time to defend the United States and Canada from the evil machinations of super-villains, Hitler, Mussolini, and other World War II era enemies. By 1941, War Nurse Pat Parker, Miss America, Pat Patriot, and Miss Victory were but a few of the patriotic female characters who had appeared in comics to fight villains and promote the war effort. These characters had all but disappeared by 1946, a testament to their limited wartime relevance. Though Nelvana of the Northern Lights (hereafter “Nelvana”) and Wonder Woman first appeared alongside the others in 1941, they have proven to be more enduring superheroes than their crime-fighting colleagues. In particular, Nelvana was one of five comic book characters depicted in the 1995 Canada Post Comic Book Stamp Collection, and Wonder Woman was one of ten DC Comics superheroes featured in the 2006 United States Postal Service (USPS) Commemorative Stamp Series. The uniquely enduring iconic statuses of Nelvana and Wonder Woman result from their adventures and character development in the context of World War II and the political, social, and cultural climates in their respective English-speaking areas of North America. Through a comparative analysis of Wonder Woman and Nelvana, two of their 1942 adventures, and their subsequent deployment through government-issued postage stamps, I will demonstrate how the two characters embody and reinforce what Michael Billig terms “banal nationalism” in their respective national contexts. -

TPTV Schedule March 1St to March 7Th

st th TPTV Schedule March 1 to March 7 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 01 00:05 King David 1985. Drama. Directed by Bruce Beresford. Stars Richard Gere, Alice Krige, Denis Quilley & Mar 21 Edward Woodward. Epic historical drama about the life of the second King of the Kingdom of Israel, David. (AVAILABLE SUBTITLES) Mon 01 02:15 The Immortal Orson 2019. Documentary. Director: Chris Wade. Stars: Dorian Bond, Norman Eshley & Henry Jaglom. Mar 21 Welles A documentary exploring the life and career of the esteemed Orson Welles. Mon 01 03:30 The Hideout 1956. Drama. Director: Peter Graham Scott. Cast: Dermot Walsh, Rona Anderson & Sam Kydd. Mar 21 An insurance investigator receives a suitcase full of cash. His search leads him to the sister of a smuggler. Mon 01 04:45 The Girl From Willow 1975. Drama. Director: Gay Ashby. A man offers a young woman a lift, only to discover later Mar 21 Green that she went missing two years ago. Part of the Women Amateur Filmmakers Collection. Mon 01 05:00 The Westerner Line Camp. 1962. Western Series created by Sam Peckinpah and starring Brian Keith. One of Mar 21 the most sophisticated westerns for its time or any other. (S1, E10) Mon 01 05:30 Tate The Reckoning. 1960. Western. Stars David McLean. The adventures of a one-armed gun Mar 21 fighter who lost his arm in the Civil War. (S1, E10) Mon 01 06:00 Blind Corner 1965. Drama. Director: Lance Comfort. Stars William Sylvester, Barbara Shelley & Elizabeth Mar 21 Shepherd. The wife of a blind composer plots to murder her husband after he learns of her affair. -

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T. -

Rio Content Market 2015 Newsletter

Rio Content Market 2015 Newsletter > 5 ANCIENT HISTORY > 6 GREAT MYTHS (THE) AUTHOR Tales of love, sex, power, betrayal, heinous crimes, unbearable François BUSNEL DIRECTOR separations, atrocious revenge, and metamorphoses - the poetic François BUSNEL force of the myths has crossed the centuries. COPRODUCERS ARTE FRANCE, ROSEBUD PRODUCTIONS "The Great Myths" documentary series sets out to recount these ancient stories using FORMAT animations created especially for the occasion, and illustrations chosen from the entire 20 x 26 ', 2015 history of art. This dynamic blend, a bridge between modernity and history, ancient AVAILABLE RIGHTS TV - DVD - VOD - Non-theatrical rights - narrative and contemporary dramatic art, is a new way to discover or re-discover this part Internet of our universal heritage. VERSIONS English - German - French TERRITORY(IES) PREVISIONAL DELIVERY: NOVEMBER 2015 Worldwide. Episodes : THESEUS - ORPHEUS - PERSEUS - MEDEA - APOLLO - PROMETHEUS - OEDIPUS - DIONYSUS - HADES - ANTIGONE - ZEUS - ATHENA - ICARUS - CHIRON - HERA - APHRODITE - HERCULES - HERMES - BELLEROPHON - EROS. CONTEMPORARY HISTORY > 7 ACTION T4: A DOCTOR UNDER NAZISM DIRECTOR This documentary recounts his story and through the man's story, Catherine BERNSTEIN COPRODUCER that of the so-called "Action T4", which consisted of eliminating ZADIG PRODUCTIONS physical and mental disabilities and those people considered by the FORMAT Nazi regime to be useless or "asocial". 1 x 52 ', 2014 AVAILABLE RIGHTS Doctor Julius Hallervorden, a major name in the science of brain pathology, first benefited TV - DVD - VOD - Non-theatrical rights - from, then contributed to the systematic assassination ordered by Hitler of German Internet mentally ill persons, by recovering the brains of 690 victims. He nevertheless pursued a VERSIONS English - French brilliant post-war career, in all impunity, and died covered in honours. -

Cartooning America: the Fleischer Brothers Story

NEH Application Cover Sheet (TR-261087) Media Projects Production PROJECT DIRECTOR Ms. Kathryn Pierce Dietz E-mail: [email protected] Executive Producer and Project Director Phone: 781-956-2212 338 Rosemary Street Fax: Needham, MA 02494-3257 USA Field of expertise: Philosophy, General INSTITUTION Filmmakers Collaborative, Inc. Melrose, MA 02176-3933 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story Grant period: From 2018-09-03 to 2019-04-19 Project field(s): U.S. History; Film History and Criticism; Media Studies Description of project: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story is a 60-minute film about a family of artists and inventors who revolutionized animation and created some of the funniest and most irreverent cartoon characters of all time. They began working in the early 1900s, at the same time as Walt Disney, but while Disney went on to become a household name, the Fleischers are barely remembered. Our film will change this, introducing a wide national audience to a family of brothers – Max, Dave, Lou, Joe, and Charlie – who created Fleischer Studios and a roster of animated characters who reflected the rough and tumble sensibilities of their own Jewish immigrant neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. “The Fleischer story involves the glory of American Jazz culture, union brawls on Broadway, gangsters, sex, and southern segregation,” says advisor Tom Sito. Advisor Jerry Beck adds, “It is a story of rags to riches – and then back to rags – leaving a legacy of iconic cinema and evergreen entertainment.” BUDGET Outright Request 600,000.00 Cost Sharing 90,000.00 Matching Request 0.00 Total Budget 690,000.00 Total NEH 600,000.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms. -

Thinking About Journalism with Superman 132

Thinking about Journalism with Superman 132 Thinking about Journalism with Superman Matthew C. Ehrlich Professor Department of Journalism University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL [email protected] Superman is an icon of American popular culture—variously described as being “better known than the president of the United States [and] more familiar to school children than Abraham Lincoln,” a “triumphant mixture of marketing and imagination, familiar all around the world and re-created for generation after generation,” an “ideal, a hope and a dream, the fantasy of millions,” and a symbol of “our universal longing for perfection, for wisdom and power used in service of the human race.”1 As such, the character offers “clues to hopes and tensions within the current American consciousness,” including the “tensions between our mythic values and the requirements of a democratic society.”2 This paper uses Superman as a way of thinking about journalism, following the tradition of cultural and critical studies that uses media artifacts as tools “to size up the shape, character, and direction of society itself.”3 Superman’s alter ego Clark Kent is of course a reporter for a daily newspaper (and at times for TV news as well), and many of his closest friends and colleagues are also journalists. However, although many scholars have analyzed the Superman mythology, not so many have systematically analyzed what it might say about the real-world press. The paper draws upon Superman’s multiple incarnations over the years in comics, radio, movies, and television in the context of past research and criticism regarding the popular culture phenomenon. -

KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin with Leah Wilson

Other Titles in the Smart Pop Series Taking the Red Pill Science, Philosophy and Religion in The Matrix Seven Seasons of Buffy Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Television Show Five Seasons of Angel Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Vampire What Would Sipowicz Do? Race, Rights and Redemption in NYPD Blue Stepping through the Stargate Science, Archaeology and the Military in Stargate SG-1 The Anthology at the End of the Universe Leading Science Fiction Authors on Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Finding Serenity Anti-heroes, Lost Shepherds and Space Hookers in Joss Whedon’s Firefly The War of the Worlds Fresh Perspectives on the H. G. Wells Classic Alias Assumed Sex, Lies and SD-6 Navigating the Golden Compass Religion, Science and Dæmonology in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials Farscape Forever! Sex, Drugs and Killer Muppets Flirting with Pride and Prejudice Fresh Perspectives on the Original Chick-Lit Masterpiece Revisiting Narnia Fantasy, Myth and Religion in C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles Totally Charmed Demons, Whitelighters and the Power of Three An Unauthorized Look at One Humongous Ape KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin WITH Leah Wilson BENBELLA BOOKS • Dallas, Texas This publication has not been prepared, approved or licensed by any entity that created or produced the well-known movie King Kong. “Over the River and a World Away” © 2005 “King Kong Behind the Scenes” © 2005 by Nick Mamatas by David Gerrold “The Big Ape on the Small Screen” © 2005 “Of Gorillas and Gods” © 2005 by Paul Levinson by Charlie W.