Undersea Dragons Lyle Goldstein and William Murray China's Maturing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Pueblo's Wake

IN PUEBLO’S WAKE: FLAWED LEADERSHIP AND THE ROLE OF JUCHE IN THE CAPTURE OF THE USS PUEBLO by JAMES A. DUERMEYER Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN U.S. HISTORY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2016 Copyright © by James Duermeyer 2016 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to my professor and friend, Dr. Joyce Goldberg, who has guided me in my search for the detailed and obscure facts that make a thesis more interesting to read and scholarly in content. Her advice has helped me to dig just a bit deeper than my original ideas and produce a more professional paper. Thank you, Dr. Goldberg. I also wish to thank my wife, Janet, for her patience, her editing, and sage advice. She has always been extremely supportive in my quest for the masters degree and was my source of encouragement through three years of study. Thank you, Janet. October 21, 2016 ii Abstract IN PUEBLO’S WAKE: FLAWED LEADERSHIP AND THE ROLE OF JUCHE IN THE CAPTURE OF THE USS PUEBLO James Duermeyer, MA, U.S. History The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Joyce Goldberg On January 23, 1968, North Korea attacked and seized an American Navy spy ship, the USS Pueblo. In the process, one American sailor was mortally wounded and another ten crew members were injured, including the ship’s commanding officer. The crew was held for eleven months in a North Korea prison. -

Tom Clancy’S “Patriot Games,” Released in 1992

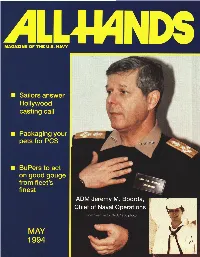

rn Packaging your ADM Jeremy .. Sa, Chief of Naval Operations From Seaman to CNO, 1956 photo D 4”r Any dayin the Navv J May 18,1994, is just like any other day in the Navy, butwe want you to photograph it. 0th amateur and professional civilian and military photographers are askedto record what's happening on their ship or installa- tion on Wednesday, May 18, 1994, for a special photo featureto appear in theOc- tober edition ofAll Hands magazine. We need photos that tell a story and capture fac-the es of sailors, Marines, their families and naval employ- ees. We're looking for imagination and creativity- posed shots will be screenedout. Shoot what is uniqueto your ship or installation, something you may see everyday but others may never get the opportunityto experience. formation. This includes full name, rank and duty sta- We're looking for the best photos from the field, for a tion of the photographer; the names and hometowns worldwide representation of what makes theNavy what of identifiable people in the photos; details on what's it is. happening in the photo; and where the photo tak- was Be creative. Use different lenses - wide angle and en. Captions must be attached individuallyto each pho- telephoto -to give an ordinaryphoto afresh look. Shoot to or slide. Photos must be processed and received by from different angles and don't be afraid to bend those All Hands by June 18, 1994. Photos will not be re- knees. Experiment with silhouettes and time-exposed turned. shots. Our mailing address is: Naval Media Center, Pub- Accept the challenge! lishing Division, AlTN: All Hands, Naval Station Ana- Photos must be shot in the 24-hour period of May costia, Bldg. -

Submarines in the United States Navy - Wikipedia Page 1 of 13

Submarines in the United States Navy - Wikipedia Page 1 of 13 Submarines in the United States Navy There are three major types of submarines in the United States Navy: ballistic missile submarines, attack submarines, and cruise missile submarines. All submarines in the U.S. Navy are nuclear-powered. Ballistic subs have a single strategic mission of carrying nuclear submarine-launched ballistic missiles. Attack submarines have several tactical missions, including sinking ships and subs, launching cruise missiles, and gathering intelligence. The submarine has a long history in the United States, beginning with the Turtle, the world's first submersible with a documented record of use in combat.[1] Contents Early History (1775–1914) World War I and the inter-war years (1914–1941) World War II (1941–1945) Offensive against Japanese merchant shipping and Japanese war ships Lifeguard League Cold War (1945–1991) Towards the "Nuclear Navy" Strategic deterrence Post–Cold War (1991–present) Composition of the current force Fast attack submarines Ballistic and guided missile submarines Personnel Training Pressure training Escape training Traditions Insignia Submarines Insignia Other insignia Unofficial insignia Submarine verse of the Navy Hymn See also External links References https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Submarines_in_the_United_States_Navy 3/24/2018 Submarines in the United States Navy - Wikipedia Page 2 of 13 Early History (1775–1914) There were various submersible projects in the 1800s. Alligator was a US Navy submarine that was never commissioned. She was being towed to South Carolina to be used in taking Charleston, but she was lost due to bad weather 2 April 1863 off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. -

The Pueblo Incident

The Pueblo Incident Held hostage for 11 months, this Navy crew was freed two days before Christmas One of Pueblo's crew (left) checks in after crossing the Bridge of No Return at the Korean Demilitarized Zone, on Dec. 23, 1968, following his release by the North Korean government. He is wearing clothing provided by the North Koreans. The Pueblo (AGER-2) and her crew had been captured off Wonsan on January 23, 1968. Note North Korean troops in the background. (Navy) On the afternoon of Jan. 23, 1968, an emergency message reached the aircraft carrier Enterprise from the Navy vessel Pueblo, operating in the Sea of Japan. A North Korean ship, the message reported, was harassing Pueblo and had ordered it to heave to or be fired upon. A second message soon announced that North Korean vessels had surrounded Pueblo, and one was trying to put an armed party aboard the American ship. By then it was clear something was seriously amiss, but Enterprise, which was operating 500 miles south of Wonsan, North Korea, was unsure how to respond. “Number one,” recalled Enterprise commanding officer Kent Lee, “we didn’t know that there was such a ship as Pueblo.…By the time we waited for clarification on the message, and by the time we found out that Pueblo was a U.S. Navy ship…it was too late to launch.” This confusion was replicated elsewhere. Messages had started to flood the nation’s capital as well, but with similar results. Inside the White House Situation Room, watch officer Andrew Denner quickly recognized the gravity of the incident and started making calls but could obtain little information. -

English Comes from the French: Guerre De Course

The Maritime Transport War - Emphasizing a strategy to interrupt the enemy sea lines of communication1 (SLOCs) - ARAKAWA Kenichi Preface Why did the Imperial Japanese Navy not aggressively develop a strategy to interrupt the enemy sea line of communication (SLOC) during the Second World War? Japan’s SLOC connecting her southern and Asian continental fronts to the mainland were destroyed mainly by the U.S. submarine warfare. Consequently, Japanese forces suffered from shortages of provisions as well as natural resources necessary for her military power. Furthermore, neither weapons nor provisions could be delivered to the fronts due to the U.S. operations to disrupt the Japanese SLOCs between the battlegrounds and the Japanese home island. Thus soldiers on the front were threatened with starvation even before the battle. In contrast, the U.S. and British military forces supported long logistical supply lines to their Asian and Pacific battlegrounds. However, there are no records indicating that the Imperial Japanese Navy attempted to interrupt these vital sea lines. Surely Japanese officers were aware of the German use of submarines in World WarⅠ. Why did the Imperial Japanese Navy not adopt a guerre de course strategy, that is a strategy targeting the enemy merchant marine and logistical lines? The most comprehensive explanation indicates that the Imperial Japanese Navy had no doctrine providing for this kind of warfare. The core of its naval strategy was the doctrine of “decisive battles at any cost.” Under the Japanese naval doctrine submarines were meant to contribute to fleet engagements not to have an independent combat role or to target anything but the enemy fleet. -

The Submarine Review December 2017 Paid Dulles, Va Dulles, Us Postage Permit No

NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE DECEMBER 2017 5025D Backlick Road NON-PROFIT ORG. FEATURES Annandale, VA 22003 US POSTAGE PAID Repair and Rebuild - Extracts; American PERMIT NO. 3 Enterprise Institute DULLES, VA Ms. Mackenzie Eaglen..........................9 2017 Naval Submarine League History Seminar Transcript.................................24 Inside Hunt for Red October THE SUBMARINE REVIEW DECEMBER 2017 THE SUBMARINE REVIEW CAPT Jim Patton, USN, Ret..................67 Awardees Recognized at NSL Annual Symposium...........................................73 ESSAYS Battle of the Atlantic: Command of the Seas in a War of Attrition LCDR Ryan Hilger, USN...............85 Emerging Threats to Future Sea Based Strategic Deterrence CDR Timothy McGeehan, USN, .....97 Innovation in C3 for Undersea Assets LT James Davis, USN...................109 SUBMARINE COMMUNITY Canada’s Use of Submarines on Fisheries Patrols: Part 2 Mr. Michael Whitby.......................118 Career Decisions - Submarines RADM Dave Oliver, USN, Ret......125 States Put to Sea Mr. Richard Brown.........................131 Interview with a Hellenic Navy Subma- rine CO CAPT Ed Lundquist, USN, Ret.....144 The USS Dallas: Where Science and Technology Count Mr. Lester Paldy............................149 COVER_AGS.indd 1 12/11/17 9:59 AM THE SUBMARINE REVIEW DECEMBER 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Letter................................................................................................2 Editor’s Notes.....................................................................................................3 -

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress September 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32665 Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the annual rate of Navy ship procurement, the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans, and the capacity of the U.S. shipbuilding industry to execute the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years. In December 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship goal was made U.S. policy by Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115- 91 of December 12, 2017). The Navy and the Department of Defense (DOD) have been working since 2019 to develop a successor for the 355-ship force-level goal. The new goal is expected to introduce a new, more distributed fleet architecture featuring a smaller proportion of larger ships, a larger proportion of smaller ships, and a new third tier of large unmanned vehicles (UVs). On June 17, 2021, the Navy released a long-range Navy shipbuilding document that presents the Biden Administration’s emerging successor to the 355-ship force-level goal. The document calls for a Navy with a more distributed fleet architecture, including 321 to 372 manned ships and 77 to 140 large UVs. A September 2021 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimates that the fleet envisioned in the document would cost an average of between $25.3 billion and $32.7 billion per year in constant FY2021 dollars to procure. -

Mar 1968 - North Korean Seizure of U.S.S

Keesing's Record of World Events (formerly Keesing's Contemporary Archives), Volume 14, March, 1968 United States, Korea, Korean, Page 22585 © 1931-2006 Keesing's Worldwide, LLC - All Rights Reserved. Mar 1968 - North Korean Seizure of U.S.S. “Pueblo.” - Panmunjom Meetings of U.S. and North Korean Military Representatives. Increase in North Korean Attacks in Demilitarized Zone. - North Korean Commando Raid on Seoul. A serious international incident occurred in the Far East during the night of Jan. 22–23 when four North Korean patrol boats captured the 906-ton intelligence ship Pueblo, of the U.S. Navy, with a crew of 83 officers and men, and took her into the North Korean port of Wonsan. According to the U.S. Defence Department, the Pueblo was in international waters at the time of the seizure and outside the 12-mile limit claimed by North Korea. A broadcast from Pyongyang (the North Korean capital), however, claimed that the Pueblo–described as “an armed spy boat of the U.S. imperialist aggressor force” –had been captured with her entire crew in North Korean waters, where she had been “carrying out hostile activities.” The Pentagon statement said that the Pueblo “a Navy intelligence-collection auxiliary ship,” had been approached at approximately 10 p.m. on Jan. 22 by a North Korean patrol vessel which had asked her to identify herself. On replying that she was a U.S. vessel, the patrol boat had ordered her to heave to and had threatened to open fire if she did not, to which the Pueblo replied that she was in international waters. -

The Pueblo Incident: a Spy Ship and the Failure of American Foreign Policy'

H-Diplo DeFalco on Lerner, 'The Pueblo Incident: A Spy Ship and the Failure of American Foreign Policy' Review published on Saturday, June 1, 2002 Mitchell B. Lerner. The Pueblo Incident: A Spy Ship and the Failure of American Foreign Policy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002. xii + 320 pp. $34.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-7006-1171-3. Reviewed by Ralph L. DeFalco (USNR, College of Continuing Education, Joint Maritime Operations Department, United States Naval War College) Published on H-Diplo (June, 2002) In Harm's Way: The Tragedy and Loss of the USS Pueblo In Harm's Way: The Tragedy and Loss of the USS Pueblo On January 23, 1968, the USS Pueblo was attacked, boarded, and captured by North Korean forces. The loss of the ship and its crew was one of the most agonizing incidents of Lyndon B. Johnson's presidency and could easily have sparked another Korean war. It did not. Today, the details of the Pueblo Incident are remembered by few and unknown to most, and the incident itself is little more than a footnote to the history of the Cold War. Mitchell B. Lerner's new book, The Pueblo Incident: A Spy Ship and the Failure of American Foreign Policy, is a detailed and thoroughly researched account of the Pueblo, its mission, its capture, and the captivity of its crew. Lerner, assistant professor of history at Ohio State University, writes well and thoughtfully organizes his work. He has proved also to be a diligent researcher with the demonstrated ability to blend both primary and secondary source materials into solid narrative. -

AEGIS Radar Phase Shifters

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2006-12 Total ownership cost reduction case study : AEGIS radar phase shifters Bridger, Wray W. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/34231 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA MBA PROFESSIONAL REPORT Total Ownership Cost Reduction Case Study: AEGIS Radar Phase Shifters By: Wray W. Bridger Mark D. Ruiz December 2006 Advisors: Aruna Apte James B. Greene Approved for public release; Distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) December 2006 MBA Professional Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE: 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Total Ownership Cost Reduction Case Study: AEGIS Radar Phase Shifters 6. AUTHOR(S) Wray W. Bridger, LCDR, USN Mark D. Ruiz, Capt, USAF 7. -

US. Government Work Not Protected by U.S. Copyright. During 1982, MYSTIC Conducted Two Operations of Note

U. S . NAVY'S DEEP SUBMERGENCE FORCES By CAPT James P.WEOH 11, USM Suhrine Development GroupOhT San Diego, CA 92106 ABSTRACT Since its inception in 1970, Submarine Developmenta?d a biomedical research department. The greatest Group OWE113s functioned astine U. S. Navy's sole wealth of experience to date, however, has been with operating arm for underwater search, recovery, and deep suhergence vehicles. Hence, this paper will be rescue. As such, it maintains the largest, most directed toward recent experiences with these systems. diverse collection of DeepSuhergence assets in the world, including submarines, manned and unmanned sub- DEEP SUBMERGENCE RESCUE mersibles, search systems, diving systems, surface ships, and shore facilities. A wealth of operational The Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle(DSRV) system experiences have been acquired with these assets overhas been designed to providea quick-reaction, world- the past thirteen years in both Atlantic and Pacificwide capability to rescue personnel from a disabled Oceans, leading to the establishrnent of numerous tech-submarine, lying on the ocean atfloor less than niques and equipment developments. This paper will collapse depth. describe specific Subnarine Development Group systems and present results of several recent operations. Each of the Navy's two DSRV's (IUSTIC and AVALON) -Future glans will also be discussed. are designed to mate over the hatch of a disabled submarine and, with a crew of three, carry24 up to INTRODUCTION rescuees per trip back to safety. The outer hull, made of fiberglass reinforced plastic, 50 is feet in length The U. S. Navy's operational command for deep sub- and 8 feet in diameter. -

2. Location Street a Number Not for Pubhcaoon City, Town Baltimore Vicinity of Ststs Maryland Coot 24 County Independent City Cods 510 3

B-4112 War 1n the Pacific Ship Study Federal Agency Nomination United States Department of the Interior National Park Servica cor NM MM amy National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form dato««t«««d See instructions in How to CompMe National Raglatar Forma Type all entries—complsts applicable sections 1. Name m«toMc USS Torsk (SS-423) and or common 2. Location street a number not for pubHcaOon city, town Baltimore vicinity of ststs Maryland coot 24 county Independent City cods 510 3. Classification __ Category Ownership Status Present Use district ±> public _X occupied agriculture _X_ museum bulldlng(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure both work In progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious JL_ object in process X_ yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted Industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Baltimore Maritime Museum street * number Pier IV Pratt Street city,town Baltimore —vicinltyof state Marvlanrf 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Department of the Navy street * number Naval Sea Systems Command, city, town Washington state pc 20362 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title None has this property been determined eligible? yes no date federal state county local depository for survey records ctty, town . state B-4112 Warships Associated with World War II In the Pacific National Historic Landmark Theme Study" This theme study has been prepared for the Congress and the National Park System Advisory.Board in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Public Law 95-348, August 18, 1978. The purpose of the theme study is to evaluate sur- ~, viving World War II warships that saw action in the Pacific against Japan and '-• to provide a basis for recommending certain of them for designation as National Historic Landmarks.