Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity and Composition of Phytoplankton Around Jaitapur Coast, Maharashtra, India

Indian Journal of Geo Marine Sciences Vol. 47 (12), December 2018, pp. 2429-2441 Diversity and composition of phytoplankton around Jaitapur coast, Maharashtra, India Mayura Khot1, P. Sivaperumal1, Neeta Jadhav1, S.K. Chakraborty1, Anil Pawase2&A.K. Jaiswar1* 1ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Education, Panch Marg, Off Yari Road, Versova, Andheri (W), Mumbai - 400061, India 2Colleges of Fisheries, Shirgaon, Ratnagiri - 415602, India *[Email: [email protected]] Received 07 April 2017; revised 02 June 2017 The average phytoplankton density was observed to be highest during post-monsoon at inshore as well as offshore stations. Overall phytoplankton was comprised of Bacillariophyceae (81.4%), Dinophyceae (12%), Chrysophyceae (3%), Cyanophyceae (1.8%), Desmophyceae (2.9%) and Chlorophyceae (3.9%). A total of 86 species of phytoplankton belonging to 56 genera and 6 classes were recorded from offshore and inshore stations. A massive bloom of cyanobacteria Trichodesmium erythraeum was also sighted during the winter season. Dinoflagellates showed a peak during monsoon at inshore stations. Maximum values of diversity indices were recorded during winter at offshore and during pre-monsoon at inshore stations. [Keywords: Jaitapur, proposed nuclear power plant, phytoplankton, bloom, Trichodesmium erythraeum] Introduction other power plants hasshown temperature as an Coastal NPP sites usually consuming seawater for important factor in increasing biomass, primary coolant system and discharge warm water into the sea, productivity and changes in species dominance of thereby raising the temperature of sea water1-3. phytoplankton around the vicinity of cooling water Generally,water temperature plays an important role outlet19,20.Outcomes from Kaiga nuclear power plant ininfluencing the survival rate, growth ability, and revealed negative impact of evaluated temperature on reproduction of aquatic organisms4,5. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

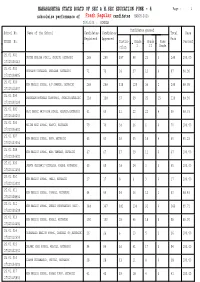

School Wise Result Statistics Report

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 25.01.001 UNITED ENGLISH SCHOOL, CHIPLUN, RATNAGIRI 289 289 197 66 23 3 289 100.00 27320100143 25.01.002 SHIRGAON VIDYALAYA, SHIRGAON, RATNAGIRI 71 71 24 27 12 4 67 94.36 27320108405 25.01.003 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, A/P SAWARDE, RATNAGIRI 288 288 118 129 36 2 285 98.95 27320111507 25.01.004 PARANJAPE MOTIWALE HIGHSCHOOL, CHIPLUN,RATNAGIRI 118 118 37 39 25 15 116 98.30 27320100124 25.01.005 HAJI DAWOOD AMIN HIGH SCHOOL, KALUSTA,RATNAGIRI 61 60 11 22 22 4 59 98.33 27320100203 25.01.006 MILIND HIGH SCHOOL, RAMPUR, RATNAGIRI 70 70 38 26 6 0 70 100.00 27320106802 25.01.007 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, BHOM, RATNAGIRI 65 63 16 30 10 4 60 95.23 27320103004 25.01.008 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, MARG TAMHANE, RATNAGIRI 67 67 17 39 11 0 67 100.00 27320104602 25.01.009 JANATA MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KOKARE, RATNAGIRI 65 65 38 24 3 0 65 100.00 27320112406 25.01.010 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, OMALI, RATNAGIRI 17 17 8 6 3 0 17 100.00 27320113002 25.01.011 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, POPHALI, RATNAGIRI 64 64 14 36 12 1 63 98.43 27320108904 25.01.012 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KHERDI-CHINCHAGHARI (SATI), 348 347 181 134 31 0 346 99.71 27320101508 25.01.013 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, NIWALI, RATNAGIRI 100 100 29 46 18 6 99 99.00 27320114405 25.01.014 RATNASAGAR ENGLISH SCHOOL, DAHIWALI (B),RATNAGIRI 26 26 6 13 5 2 26 100.00 27320112604 25.01.015 DALAWAI HIGH SCHOOL, MIRJOLI, RATNAGIRI 94 94 36 41 17 0 94 100.00 27320102302 25.01.016 ADARSH VIDYAMANDIR, CHIVELI, RATNAGIRI 28 28 13 11 4 0 28 100.00 27320104303 25.01.017 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KOSABI-FURUS, RATNAGIRI 41 41 19 18 4 0 41 100.00 27320115803 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 2 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. -

Potential of Wave Energy Power Plants Along Maharashtra Coast

POTENTIAL OF WAVE ENERGY POWER PLANTS ALONG MAHARASHTRA COAST SUDHIR KUMAR Maharashtra Energy Development Agency 191-A, MHADA Commercial Complex, Yerawada, PUNE - 411 006, INDIA. Tel.No. :020-683633/4, Fax : 683631 E-Mail : [email protected] Website : http://www.mahaurja.com ABSTRACT Sea waves are the result of transfer of mechanical energy of wind to wave energy. The wave quality varies for different periods and seasons. It is possible to have a realistic formula to calculate the overall wave energy potential. A general study of the wave nature has shown that there is potential of 40,000 MW along the Indian Coast. Similar study along the coast of Maharashtra State has shown that there are some potential sites such as Vengurla rocks, Malvan rocks, Redi, Pawas, Ratnagiri and Girye which have the average annual wave energy potential of 5 to 8 kW/m and monsoon potential of 15 to 20 kW/m. Considering this, the total potential along the 720 KM stretch of Maharashtra Coast is approximately 500 MW for wave energy power plants. Fortunately, after the decades of research and development activities all over the world, now some technologies are available commercially. Taking advantage of the situation, we need to exploit the possibility of the wave energy power plants at the identified sites by inviting the proposals from private investors / promoters / technology providers from all over the world. Approximately, they attract the private investment to the tune of Rs. 3000 crores. The Govt. of Maharashtra and Govt. of India, plans to announce the policies to attract private investors in this field on BOO (build own operate) basis. -

Biodiversity Action Plan Full Report

Final Report Project Code 2012MC09 Biodiversity Action Plan For Malvan and Devgad Blocks, Sindhudurg District, Maharashtra Prepared for Mangrove Cell, GoM i Conducting Partipicatory Rural Appraisal in the Coastal Villages of SIndhudurg District © The Energy and Resources Institute 2013 Suggested format for citation T E R I. 2013 Participatory Rural Appraisal Study in Devgad and Malvan Blocks, Sindhudurg District New Delhi: The Energy and Resources Institute 177 pp. For more information Dr. Anjali Parasnis Associate Director, Western Regional Centre Tel: 022 27580021/ 40241615 The Energy and Resources Institute E-mail: [email protected] 318, Raheja Arcade, sector 11, Fax: 022-27580022 CBD-Belapur, Navi Mumbai - 400 614, India Web: www.teriin.org ii Conducting Partipicatory Rural Appraisal in the Coastal Villages of SIndhudurg District Contents Abbrevations: .......................................................................................................................... x Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. xii 1. SINDHUDURG: AN INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 14 1.1 Climate and rainfall: ...................................................................................................... 15 1.2 Soil: ................................................................................................................................... 15 1.3 Cropping pattern:.......................................................................................................... -

NEWS on ELECTRICITY DEVELOPMENTS Issue I – March

NEWS ON ELECTRICITY DEVELOPMENTS Issue I – March 2007 (Compilation of news in February 2007) By CPSD, YASHADA and PRAYAS (Energy Group), Pune News on Electricity Developments (NED) is a monthly compilation of news prepared by Prayas (Energy Group) and CPSD, YASHADA for the participants of Training Programmes conducted by YASHADA (Yashwantrao Chavan Academy of Development Administration). Prayas is an NGO based in Pune, engaged in analysis and advocacy on power sector issues. This news update covers the key news in power sector at the national level and also in the state of Maharashtra during February 2007. P. G. Chavan DIRECTOR CPSD, YASHADA, Pune News on Electricity Developments CONTENTS 1. National Level Developments ................................................................................... 3 1.1 Merchant Power Plants.......................................................................................... 3 1.2 Restructuring of Coal Sector ................................................................................. 3 1.3 Delhi..................................................................................................................... 3 1.3.1 Tariff issues.................................................................................................... 3 1.3.2 Other consumer issues.................................................................................... 4 1.4 Ultra Mega Power Projects (UMPP)...................................................................... 5 1.5 Budget 2007......................................................................................................... -

GI Journal No. 145 1 April 30, 2021

GI Journal No. 145 1 April 30, 2021 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO. 145 APRIL 30, 2021 / VAISAKA 10, SAKA 1943 GI Journal No. 145 2 April 30, 2021 INDEX S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Official Notices 4 2 New G.I Application Details 5 3 Public Notice 6 4 GI Applications 7 Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco – GI Application No. 353 Franciacorta - GI Application No. 356 Chianti - GI Application No. 361 5 GI Authorised User Applications Kangra Tea – GI Application No. 25 Mysore Traditional Paintings – GI Application No. 32 Kashmir Pashmina – GI Application No. 46 Kashmir Sozani Craft – GI Application No. 48 Kani Shawl – GI Application No. 51 Alphonso – GI Application No. 139 Kashmir Walnut Wood Carving – GI Application No. 182 Thewa Art Work – GI Application No. 244 Vengurla Cashew – GI Application No. 489 Purulia Chau Mask – GI Application No. 565 Wooden Mask of Kushmandi – GI Application No. 566 Tirur Betel Leaf (Tirur Vettila) – GI Application No. 641 5 General Information 6 Registration Process GI Journal No. 145 3 April 30, 2021 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 145 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 30th April, 2021 / Vaisaka 10, Saka 1943 has been made available to the public from 30th April, 2021. GI Journal No. 145 4 April 30, 2021 NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS App.No. Geographical Indications Class Goods 746 Goan Bebinca -

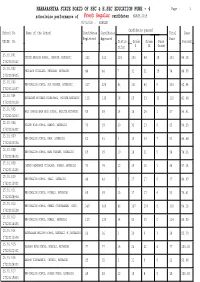

School Wise Result Statistics Report

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2019 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 25.01.001 UNITED ENGLISH SCHOOL, CHIPLUN, RATNAGIRI 313 313 115 103 68 15 301 96.16 27320100143 25.01.002 SHIRGAON VIDYALAYA, SHIRGAON, RATNAGIRI 84 84 7 31 21 15 74 88.09 27320108405 25.01.003 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, A/P SAWARDE, RATNAGIRI 327 326 83 131 83 6 303 92.94 27320111507 25.01.004 PARANJAPE MOTIWALE HIGHSCHOOL, CHIPLUN,RATNAGIRI 135 135 16 29 33 32 110 81.48 27320100124 25.01.005 HAJI DAWOOD AMIN HIGH SCHOOL, KALUSTA,RATNAGIRI 59 59 14 18 24 1 57 96.61 27320100203 25.01.006 MILIND HIGH SCHOOL, RAMPUR, RATNAGIRI 70 69 20 32 13 0 65 94.20 27320106802 25.01.007 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, BHOM, RATNAGIRI 62 61 3 10 33 7 53 86.88 27320103004 25.01.008 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, MARG TAMHANE, RATNAGIRI 69 69 10 18 21 5 54 78.26 27320104602 25.01.009 JANATA MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KOKARE, RATNAGIRI 70 70 12 39 16 1 68 97.14 27320112406 25.01.010 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, OMALI, RATNAGIRI 44 44 3 17 17 0 37 84.09 27320113002 25.01.011 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, POPHALI, RATNAGIRI 69 69 15 17 17 4 53 76.81 27320108904 25.01.012 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KHERDI-CHINCHAGHARI (SATI), 360 360 86 147 100 6 339 94.16 27320101508 25.01.013 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, NIWALI, RATNAGIRI 120 120 34 50 30 0 114 95.00 27320114405 25.01.014 RATNASAGAR ENGLISH SCHOOL, DAHIWALI (B),RATNAGIRI 26 26 3 14 4 3 24 92.30 27320112604 25.01.015 DALAWAI HIGH SCHOOL, MIRJOLI, RATNAGIRI 77 77 14 26 31 6 77 100.00 27320102302 25.01.016 ADARSH VIDYAMANDIR, CHIVELI, RATNAGIRI 25 25 3 11 9 0 23 92.00 27320104303 25.01.017 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KOSABI-FURUS, RATNAGIRI 39 39 12 19 8 0 39 100.00 27320115803 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 2 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2019 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. -

Pincode Officename Mumbai G.P.O. Bazargate S.O M.P.T. S.O Stock

pincode officename districtname statename 400001 Mumbai G.P.O. Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Bazargate S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 M.P.T. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Stock Exchange S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Tajmahal S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Town Hall S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Kalbadevi H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 S. C. Court S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Thakurdwar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 B.P.Lane S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Mandvi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Masjid S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Null Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Ambewadi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Charni Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Chaupati S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Girgaon S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Madhavbaug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Opera House S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Asvini S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Holiday Camp S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 V.W.T.C. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400006 Malabar Hill S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Bharat Nagar S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 S V Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Grant Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 N.S.Patkar Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Tardeo S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Mumbai Central H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 J.J.Hospital S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Kamathipura S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Falkland Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 M A Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Noor Baug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Chinchbunder S.O -

A Regional Assessment of the Potential for Co2 Storage in the Indian Subcontinent

A REGIONAL ASSESSMENT OF THE POTENTIAL FOR CO2 STORAGE IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT Technical Study Report No. 2008/2 May 2008 This document has been prepared for the Executive Committee of the IEA GHG Programme. It is not a publication of the Operating Agent, International Energy Agency or its Secretariat. INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY The International Energy Agency (IEA) was established in 1974 within the framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to implement an international energy programme. The IEA fosters co-operation amongst its 26 member countries and the European Commission, and with the other countries, in order to increase energy security by improved efficiency of energy use, development of alternative energy sources and research, development and demonstration on matters of energy supply and use. This is achieved through a series of collaborative activities, organised under more than 40 Implementing Agreements. These agreements cover more than 200 individual items of research, development and demonstration. The IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme is one of these Implementing Agreements. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND CITATIONS This report was prepared as an account of the work sponsored by the IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme, its members, the International Energy Agency, the organisations listed below, nor any employee or persons acting on behalf of any of them. In addition, none of these make any warranty, express or implied, assumes any liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product of process disclosed or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights, including any parties intellectual property rights. -

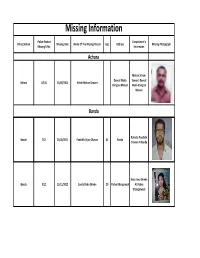

Missing Persons

Missing Information Police Station Complainant's Police Station Missing Date Name Of The Missing Person Age Address Missing Photograph Missing R.No. Informaion Achara Mohan Sitram Devual Wada Sawant Devual Achara 03\15 15/08/2015 Nilesh Mohan Sawant Vaingani Malvan Wada Vaingani Malvan Banda Rohidas Pundalik Banda 2\11 23/03/2011 Pandulik Arjun Chavan 65 Banda Chavan At Banda Badu Janu Shinde Banda 5\12 11/11/2012 Savita Dadu Shinde 20 Padve Dhangrwadi At Padve Dhangarwadi Mithun Gulabrao Banda 1\13 04-Nov Maithali Mithun Naik 23 At Asni Naik At Asni Dodamarg At Kudase Kujvan/Vilan Jepsh Dodamarg 4\12 02/12/2012 Dysai Kujvan Kelkipati 31 Vanosewadi Tal Kelkepati Dodamarg At Kudase Kujvan/Vilan Jepsh Dodamarg 4\12 02/12/2012 Joseph Kujvan Kelkipati 10 Vanosewadi Tal Kelkepati Dodamarg At Kudase Kujvan/Vilan Jepsh Dodamarg 4\12 02/12/2012 Mari Kujvan Kelkipat 8 Vanosewadi Tal Kelkepati Dodamarg Sanjay Sharad Kudse Tal Dodamarg 10\14 29/09/2013 Anil Sharad Patekar 31 Patekar At Kudse Dodamarg Tal Dodamarg Jaivant Zilu Desai Shervali Tal Dodamarg 07\14 05/02/2014 Yashwant Zilu Desai 50 At Shervali Tal Dodamarg Dodamarg At Khanayele Dodamarg 11\14 26/06/2014 Chandrakant Vithoba Sawant 45 Wagheriwadi Tal Dodamarg Sharad Bhikaji Parb At Sateli Bhedshi Dodamarg 01\15 12/02/2014 Bhikaji Mukund Parab 65 At Sateli Bhedshi Thorle Bharad Thorle Bharad Bhagashe Bhaskar At Kudase Dodamarg 5\15 24/06/2015 Bhaskar Fati Kotalve 60 Kotvle At Kudase Devulwadi Devulwadi Fatu Shankar At Vijghar Tal Dodamarg 06\15 13/07/2015 Tarkar Shankar Kamble 40 Kambale -

Survey of Important Foliage Pests of Mango from South Konkan Region of Maharashtra

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2019; 7(1): 684-686 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 Survey of important foliage pests of mango from JEZS 2019; 7(1): 684-686 © 2019 JEZS south Konkan region of Maharashtra Received: 01-11-2018 Accepted: 04-12-2018 AY Munj AY Munj, BN Sawant, KV Malshe, RM Dheware and AL Narangalkar Jr. Entomologist, Regional Fruit Research Station, Vengurle, Abstract Sindhudurg, Maharashtra, India Mango hopper, thrips, shoot borer and leaf miner are the important pests of mango in Konkan region of BN Sawant Maharashtra. Also, the incidence of other pests like mealy bug, midge and scale is increasing. However, Scientist, Extension Education, their exact status in the South Konkan region is not known. Therefore, a fixed plot survey was conducted Regional Fruit Research Station, to know the status of important pests of mango in the South Konkan region of Maharashtra during the Vengurle, Sindhudurg, vegetative flush and flowering period of 2015-16 and 2016-17. Ten mango trees were selected at five Maharashtra, India different locations of the South Konkan region for recording observations which were kept unsprayed. The observations on the intensity of important pests was recorded once in a month from October to KV Malshe February. The results revealed that during vegetative flush and flowering period, there were seven Jr. Horticulturist, Mango important foliage pests viz., mango hopper, thrips, midge, shoot borer, leaf miner, mealy bug and scale. Regional Sub Centre, Girye Mango hopper and thrips were observed as the major pests, whereas, leaf miner, shoot borer, mealy bug, Devgad, Sindhudurg, midge and scale insect were observed as the minor pests of mango in the South Konkan region of Maharashtra, India Maharashtra.