History of Trade an Commerce in Goa 1878-1961

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY 2016 AFI Annual Report. (2017). Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/publica- tions/2017-05/2016%20AFI%20Annual%20Report.pdf. A Law of the Abolition of Currencies in a Small Denomination and Rounding off a Fraction, July 15, 1953, Law No.60 (Shōgakutsūka no seiri oyobi shiharaikin no hasūkeisan ni kansuru hōritsu). Retrieved April 11, 2017, from https:// web.archive.org/web/20020628033108/http://www.shugiin.go.jp/itdb_ housei.nsf/html/houritsu/01619530715060.htm. About PBC. (2018, August 21). The People’s Bank of China. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from http://www.pbc.gov.cn/english/130712/index.html. About Us. Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https:// www.afi-global.org/about-us. AFI Official Members. Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/inlinefiles/AFI%20 Official%20Members_8%20February%202018.pdf. Ahamed, L. (2009). Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World. London: Penguin Books. Alderman, L., Kanter, J., Yardley, J., Ewing, J., Kitsantonis, N., Daley, S., Russell, K., Higgins, A., & Eavis, P. (2016, June 17). Explaining Greece’s Debt Crisis. The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2018, from https://www.nytimes. com/interactive/2016/business/international/greece-debt-crisis-euro.html. Alesina, A. (1988). Macroeconomics and Politics (S. Fischer, Ed.). NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 3, 13–62. Alesina, A. (1989). Politics and Business Cycles in Industrial Democracies. Economic Policy, 4(8), 57–98. © The Author(s) 2018 355 R. Ray Chaudhuri, Central Bank Independence, Regulations, and Monetary Policy, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-58912-5 356 BIBLIOGRAPHY Alesina, A., & Grilli, V. -

Inland Waters of Goa Mandovi River and Zuari River of River Mandovi on Saturday, the 19Th Deceriber, 2020 and Sunday

MOST IMMEDIATE Government of Goa, Captain of Ports Department, No.C-23011 / 12/ c303 \ Panaji, Goa. Dated: 15-12-2020. NOTICE TO MARINERS Inland waters of Goa Mandovi River and Zuari River It is hereby notified that the Hon'ble President of India, will be visiting Goa to launch the ceremony for the celebrations of the 60th year of Fre-edom on the banks of River Mandovi on Saturday, the 19th Deceriber, 2020 and Sunday, the 20th December, 2020. Therefore, all Owners/Masters of the barges, passengers launches, ferry boats, tindels of fishing trawlers and operators of the mechanized and non- mechanized crafts, including the tourist boats, cruise boats, etc. areWARRED NOT ro jvAVTGATE in the Mandovi river beyond Captain of Ports towards Miramar side and in the Zuari river near the vicinity of Raj Bhavan on Saturday, the 19th December, 2020 and Sunday, the 20th December, 2020. v]o[at]ons of the above shall be viewed seriously EL, (Capt. James Braganza) Captain of Ports Forwarded to: - 1.:ehf:rpny6es¥ope;;nutren]::t::Obfe:::icge'NSoe.cuDr;:ysupn/£5'E%[t£RfTO+/P]agn6aj];'2923-d¥t£:a 14-12-2020. 2. The Chief Secretary, Secretariat, Porvorim, `Goa. 3. The Secretary (Ports), Secretariat, Porvorim,. Goa. 4. The Flag Officer, Headquarter, Goa Naval Area, Vasco-da-Gama, Goa - 403802. 5. The Director General of Police, Police Headquarters, Panaji, Goa. 6. The Chairman, Mormugao Port Trust, Headland Sada, Vasco, Goa. 7. The Director of Tourism, Panaji. 8. The Director of Information and Publicity, Panaji---Goa. 9. The Deputy Captain of Ports, Captain of Ports Department,.Panaji, Goa. -

Mormugao Port Trust

Mormugao Port Trust Preparation of a Business Plan FINAL REPORT March 2007 Volume I of II (Chapter 1 to 5) Halcrow Group Limited Halcrow Consulting India Ltd In Association with Ernst & Young Private Limited Mormugao Port Trust Preparation of a Business Plan FINAL REPORT March 2007 Volume I of II (Chapter 1 to 5) Halcrow Group Limited Halcrow Consulting India Ltd In Association with Ernst & Young Private Limited Halcrow Group Limited Vineyard House, 44 Brook Green Hammersmith, London W6 7BY, United Kingdom Tel+44 (0)20 7602 7282 Fax +44 (0)20 7603 0095 Halcrow Consulting India Limited 912, Solitaire Corporate Park, Chakala, Andheri (E), Mumbai - 400093, India Tel +91 22 4005 4748 Fax +91 22 4005 4750 www.halcrow.com Halcrow Group Limited has prepared this report in accordance with the instructions of their client Mormugao Port Trust, for their sole and specific use. Any other persons who use any information contained herein do so at their own risk. © Halcrow Group Limited 2007 Mormugao Port Trust Preparation of a Business Plan FINAL REPORT Volume I of II (Chapter 1 to 5) Contents Amendment Record Uuv r uhirrvrqhqhrqrqhsyy) Dr Srvv 9rp vv 9hr Tvtrq Drq8yvr Ari h 9S7 !& ! Drq8yvr Hh pu!& 9S7 Contents E Executive Summary E-1 ! " # $ % ! " # $ $ % & ' ( ) % * ! ! " N '( () ! * + () , # - . ! % / N ) () + * , *! N $!! ./ & " )$ " +0 1 200 * 0 * , *! N !* ( & * # - * ) () ) * , *! -

International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage

Abstract Volume: International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Abstract Volume: Intenational Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage 21th - 23rd August 2013 Sri Lanka Foundation, Colombo, Sri Lanka Editor Anura Manatunga Editorial Board Nilanthi Bandara Melathi Saldin Kaushalya Gunasena Mahishi Ranaweera Nadeeka Rathnabahu iii International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Copyright © 2013 by Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. First Print 2013 Abstract voiume: International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage Publisher International Association for Asian Heritage Centre for Asian Studies University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. ISBN 978-955-4563-10-0 Cover Designing Sahan Hewa Gamage Cover Image Dwarf figure on a step of a ruined building in the jungle near PabaluVehera at Polonnaruva Printer Kelani Printers The views expressed in the abstracts are exclusively those of the respective authors. iv International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 In Collaboration with The Ministry of National Heritage Central Cultural Fund Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology Bio-diversity Secratariat, Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy v International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Message from the Minister of Cultural and Arts It is with great pleasure that I write this congratulatory message to the Abstract Volume of the International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage, collaboratively organized by the Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Ministry of Culture and the Arts and the International Association for Asian Heritage (IAAH). It is also with great pride that I join this occasion as I am associated with two of the collaborative bodies; as the founder president of the IAAH, and the Minister of Culture and the Arts. -

Indicative Pharmacy List for Oximeter

Licence Register Food & Drugs Administration Print Date : 31-Jul-2020 Sr/Firm No Firm Name , I.C / Manager Firm Address Issue Dt,Validity Cold Storage District / R.Pharmacist , Competent Person Dt,Renewal Dt, 24 Hr Open Firm Cons. Inspection Dt Lic App CIRCLE : Goa Head Office 1 om medical store chemist & druggist shop no. 305/1 franetta bldg, station road 23-Jan-2012 Yes 10081 mr. pradip p. naik curchorem goa 403706 22-Jan-2022 No SGO -D1301-annapurneshwari sherkhane Ph. 08322652835 Taluka :QUE 23-Jan-2017 AH PRO No C.P M. 9822155619 16-Feb-2017 2 ayushya medicentre chemist & druggist 2294,ground floor dr. buvaji family welfare 11-May-2007 Yes 10088 shaikh salim centre curchorem 403706 10-May-2022 No SGO -D78-mr.shaik salim Ph. Taluka :QUE 11-May-2017 AH PRO No C.P M. 9922769967 07-Jun-2017 3 kuntal medical stores chemist & druggist fgs-5 h.no.266 ground floor angelica arcade 11-Feb-2002 Yes 10091 mr. premanad phaldesai valetembi 403705 10-Feb-2022 No SGO -D1040-mr / phaldesai premanand krishan Ph. 08322664012 Taluka :QUE 11-Feb-2017 AH PRO No C.P M. 9823045316 12-Sep-2017 4 rohit chemist & druggist 4,h no 59 vaikunth bhavan,near petrol 14-Mar-2005 Yes 10092 mrs. nirmala r. naik pump quepem 403705 13-Mar-2025 No SGO -D746-naik ramdas pandhari Ph. 08322664441 Taluka :QUE 14-Mar-2020 AH PRO No C.P M. 9850469430 19-Jun-2018 5 maa medical store chemist & druggist shop no.1 j.k. chambers,near kadamba bus 18-May-1998 Yes 10103 mr. -

O. G. Series III No. 4 Pmd.Pmd

Reg. No. GR/RNP/GOA/32 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 24th April, 2014 (Vaisakha 4, 1936) SERIES III No. 4 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Note:- There is one Supplementary issue to the Official Order Gazette, Series III No. 3 dated 17-4-2014 namely, No. 5/S(4-1691)/05/DT/4061 Supplement dated 22-4-2014 from pages 81 to 96 regarding Notification from Department of The registration of Vehicle No. GA-02/V-3210 Finance [Directorate of Small Savings & Lotteries belonging to Shri Menino Cardozo, resident of (Goa State Lotteries)]. H. No. 626, Pedda, Varca, Taluka Salcete, Goa, under the Goa Registration of Tourist Trade Act, 1982 GOVERNMENT OF GOA entered in Register No. 24 at page No. 32 is hereby cancelled as the said Tourist Taxi has been Department of Tourism converted into a private vehicle with effect from ___ 01-10-2012 bearing No. GA-02/J-9343 Panaji, 21st January, 2014.— The Dy. Director of Order Tourism & Prescribed Authority (South Zone Office), No. 5/S(4-459)/2014-DT/4070 Pamela Mascarenhas. ____________ The registration of Vehicle No. GA-02/T-3144 Order belonging to Shri Shaikh Rajiq Muzawar, resident of No. 5/S(4-1324)/2003-DT/4062 H. No. 559, Pedda, Uttordoxi, Varca, Taluka Salcete, Goa, under the Goa Registration of Tourist Trade The registration of Vehicle No. GA-02/V-3129 Act, 1982 entered in Register No. 12 at page No. 7 belonging to Shri Lorno Rebello, resident of H. No. 160, Rodrigues Waddo, Cavelossim, Taluka Salcete, is hereby cancelled as the said Tourist Taxi has Goa, under the Goa Registration of Tourist Trade been converted into a private vehicle with effect Act, 1982 entered in Register No. -

Mormugao Port Trust

Mormugao Port Trust Techno-Economic Feasibility Study for the Proposed Capital Dredging of the Port for Navigation of Cape Size Vessels Draft Report December 2014 This document contains information that is proprietary to Mormugao Port Trust (MPT), which is to be held in confidence. No disclosure or other use of this information is permitted without the express authorization of MPT. Executive summary Background Mormugao Port Trust Page iii Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background .................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope of Work ............................................................................................... 2 1.3 Intent of the report .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Format of the report ....................................................................................... 3 2 Site Characteristics .............................................................................. 4 2.1 Geographical Location ................................................................................... 4 2.2 Topography and Bathymetry .......................................................................... 5 2.3 Oceanographic Data ...................................................................................... 5 2.3.1 Tides ................................................................................................ -

The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada's Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities

Brown Baby Jesus: The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada’s Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities Kathryn Carrière Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Religion and Classics Religion and Classics Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Kathryn Carrière, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 I dedicate this thesis to my husband Reg and our son Gabriel who, of all souls on this Earth, are most dear to me. And, thank you to my Mum and Dad, for teaching me that faith and love come first and foremost. Abstract Employing the concepts of lifeworld (Lebenswelt) and system as primarily discussed by Edmund Husserl and Jürgen Habermas, this dissertation argues that the lifeworlds of Anglo- Indian and Goan Catholics in the Greater Toronto Area have permitted members of these communities to relatively easily understand, interact with and manoeuvre through Canada’s democratic, individualistic and market-driven system. Suggesting that the Catholic faith serves as a multi-dimensional primary lens for Canadian Goan and Anglo-Indians, this sociological ethnography explores how religion has and continues affect their identity as diasporic post- colonial communities. Modifying key elements of traditional Indian culture to reflect their Catholic beliefs, these migrants consider their faith to be the very backdrop upon which their life experiences render meaningful. Through systematic qualitative case studies, I uncover how these individuals have successfully maintained a sense of security and ethnic pride amidst the myriad cultures and religions found in Canada’s multicultural society. Oscillating between the fuzzy boundaries of the Indian traditional and North American liberal worlds, Anglo-Indians and Goans attribute their achievements to their open-minded Westernized upbringing, their traditional Indian roots and their Catholic-centred principles effectively making them, in their opinions, admirable models of accommodation to Canada’s system. -

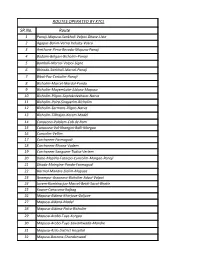

SR.No. Route ROUTES OPERATED by KTCL

ROUTES OPERATED BY KTCL SR.No. Route 1 Panaji-Mapusa-Sankhali-Valpoi-Dhave-Uste 2 Agapur-Borim-Verna Industy-Vasco 3 Amthane-Pirna-Revoda-Mapusa-Panaji 4 Badami-Belgavi-Bicholim-Panaji 5 Bamboli-Marcel-Valpoi-Signe 6 Bhiroda-Sankhali-Marcel-Panaji 7 Bibal-Paz-Cortalim-Panaji 8 Bicholim-Marcel-Mardol-Ponda 9 Bicholim-MayemLake-Aldona-Mapusa 10 Bicholim-Pilgao-Saptakoteshwar-Narva 11 Bicholim-Poira-Sinquerim-Bicholim 12 Bicholim-Sarmans-Pilgao-Narva 13 Bicholim-Tikhajan-Kerem-Madel 14 Canacona-Palolem-Cab de Ram 15 Canacona-Val-Khangini-Balli-Margao 16 Cuncolim-Vellim 17 Curchorem-Farmagudi 18 Curchorem-Rivona-Vadem 19 Curchorem-Sanguem-Tudva-Verlem 20 Dabe-Mopirla-Fatorpa-Cuncolim-Margao-Panaji 21 Dhada-Maingine-Ponda-Farmagudi 22 Harmal-Mandre-Siolim-Mapusa 23 Ibrampur-Assonora-Bicholim-Advoi-Valpoi 24 Juvem-Kumbharjua-Marcel-Betki-Savoi-Bhatle 25 Kawar-Canacona-Rajbag 26 Mapusa-Aldona-Khorjuve-Goljuve 27 Mapusa-Aldona-Madel 28 Mapusa-Aldona-Poira-Bicholim 29 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Korgao 30 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Sawantwada-Mandre 31 Mapusa-Azilo District Hospital 32 Mapusa-Bastora-Chandanwadi 33 Mapusa-Bicholim-Poira 34 Mapusa-Bicholim-Sankhali-Valpoi-Hivre 35 Mapusa-Calvi-Madel 36 Mapusa-Carona-Amadi 37 Mapusa-Colvale-Dadachiwadi-Madkai 38 Mapusa-Duler-Camurli 39 Mapusa-Karurli-Aldona-Pomburpa-Panaji 40 Mapusa-Khorjuve-Bicholim-Varpal 41 Mapusa-Marna-Siolim 42 Mapusa-Nachnola-Carona-Calvi 43 Mapusa-Palye-Succuro-Bitona-Panaji 44 Mapusa-Panaji-Fatorpha(Sunday) 45 Mapusa-Pedne-Pednekarwada-Mopa 46 Mapusa-Saligao-Calangute-Pilerne-Panaji 47 Mapusa-Siolim -

GOA and PORTUGAL History and Development

XCHR Studies Series No. 10 GOA AND PORTUGAL History and Development Edited by Charles J. Borges Director, Xavier Centre of Historical Research Oscar G. Pereira Director, Centro Portugues de Col6nia, Univ. of Cologne Hannes Stubbe Professor, Psychologisches Institut, Univ. of Cologne CONCEPT PUBLISHING COMPANY, NEW DELHI-110059 ISBN 81-7022-867-0 First Published 2000 O Xavier Centre of Historical Research Printed and Published by Ashok Kumar Mittal Concept Publishing Company A/15-16, Commercial Block, Mohan. Garden New Delhi-110059 (India) Phones: 5648039, 5649024 Fax: 09H 11 >-5648053 Email: [email protected] 4 Trade in Goa during the 19th Century with Special Reference to Colonial Kanara N . S hyam B hat From the arrival of the Portuguese to the end of the 18Ih century, the economic history of Portuguese Goa is well examined by historians. But not many works are available on the economic history of Goa during the 19lh and 20lh centuries, which witnessed considerable decline in the Portuguese trade in India. This, being a desideratum, it is not surprising to note that a study of the visible trade links between Portuguese Goa and the coastal regions of Karnataka1 is not given serious attention by historians so far. Therefore, this is an attempt to analyse the trade connections between Portuguese Goa and colonial Kanara in the 19lh century.2 The present exposition is mainly based on the administrative records of the English East India Company government such as Proceedings of the Madras Board of Revenue, Proceedings of the Madras Sea Customs Department, Madras Commercial Consultations, and official letters of the Collectors of Kanara. -

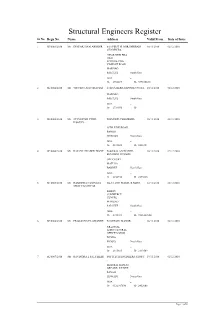

Structural Engineers Register Sr No Regn No Name Address Valid from Date of Issue

Structural Engineers Register Sr No Regn No Name Address Valid From Date of Issue 1 SE/0001/2010Mr DEEPAK S.HALARNKER 0-18,FIRST FLOOR,SHRIRAM 10/11/2010 02/12/2010 CHAMBERS, NEAR NEW ERA HIGH SCHOOL,CINE VISHANT ROAD MARGAO SALCETE South Goa GOA - O-2704693 R-, 9890108211 2 SE/0002/2010Mr VINCENT ASIF GRACIAS 47,RUA BERNARDO DE COSTA, 10/11/2010 02/12/2010 MARGAO SALCETE South Goa GOA - O-2734070 R-, 3 SE/0003/2010Mr SYLVESTER CYRIL DIAMOND CHAMBERS, 10/11/2010 02/12/2010 D'SOUZA 18TH JUNE ROAD, PANAJI TISWADI North Goa GOA - O-2231023 R-, 2453321 4 SE/0004/2010Mr RAJAN L.PRABHU MOYE B 409/410, SALDANHA 10/11/2010 02/12/2010 BUSINESS TOWERS OPP COURT MAPUSA BARDEZ North Goa GOA - O-2252730 R-, 2255626 5 SE/0005/2010Mr RABINDRA CAXINATA SO-37, 2ND FLOOR, B BLDG, 12/11/2010 02/12/2010 SINAI CACODCAR BABOY COMMERCE CENTRE MARGAO SALCETE South Goa GOA - O-2736723 R-, 9326123514 6 SE/0006/2010Mr PRAKASH S.P.LAWANDE E2,MITASU MANOR, 16/11/2010 02/12/2010 NR.ZONAL AGRICULTURAL OFFICE,SADAR PONDA PONDA North Goa GOA - O-2315615 R-, 2319569 7 SE/0007/2010Mr RAVINDRA L PALYEKAR SOFTTECH ENGINEERS SHOP 5 19/11/2010 02/12/2010 , BLOCK B, KAMAT ARCADE, ST INEZ PANAJI TISWADI North Goa GOA - O-9326107690 R-, 2452006 Page 1 of 8 Structural Engineers Register Sr No Regn No Name Address Valid From Date of Issue 8 SE/0008/2010Mr YOGESH BHOBE C4B, SAPANA REGENCY, 19/11/2010 02/12/2010 SHRIGAONKER ROAD, PANAJI TISWADI North Goa GOA - O-2423725 R-, 2222256 9 SE/0009/2010Mr ERNESTO MONIZ ALIAS 103, ANTRIENZA BLDG. -

North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ Sr

Tika Utsav 3 - North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ Sr. No. Venue Date CHC/PHC Municipality 1 CHC Pernem Mandrem ZP Hall, Mandrem 13, 14 june Morjim Sarvajanik Ganapati Hall, Morjim 15, 16 June Harmal Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav Hall, Harmal 17, 18 June Palye GPC Madhlawada, Palye 19, 20 June Keri Panchayat Hall 21, 22 June Parse Panchayat hall, Parse 23, 24, June Agarwada-Chopde Panchayat Hall 25, 26 June Virnoda Panchayat Hall 27, 28, June Korgao Panchayat Hall, Korgao 29, 30 June 2 PHC Casarvanem Varkhand Panchayat Hall, Varkhand 13, 14 june Torse Panchayat Hall 15, 16 June Chandel-Hansapur Panchayat Hall 17, 18 June Ugave Panchayat Hall 19, 20 June Ozari Panchayat Hall 21, 22 June Dhargal Panchayat Hall 23, 24, June Ibrampur Panchayat Hall 25, 26 June Halarn Panchayat Hall 27, 28, June Poroscode Panchayat Hall 29, 30 June 3 CHC Bicholim Latambarce Govt Primary School, Ladfe 13, 14, June Latambarce Govt. Primary School, Nanoda 15th June Van-Maulinguem Govt. Primary School, Maulinguem 16th Jun Menkure Govt. High School, Menkure 17, 18 June Mulgao Govt. Primary School, Shirodwadi 19, 20 Junw Advalpal Govt Primary Middle School, Gaonkarwada 21st Jun Latambarce - Usap / Bhatwadi GPS Usap 23 rd June Latambarce - Dodamarg & Kharpal GPS Dodamarg 25, 26 June Latambarce - Kasarpal & Vadaval GPS Kasarpal 27, 28 June Sal Panchayat Hall, Sal 29-Jun Sal - Kholpewadi/ Punarvasan / Shivajiraje High School, Kholpewadi 30-Jun Sirigao at Mayem Primary Health Centre, Kelbaiwada- Mayem 24th June Tika Utsav 3 - North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/