A Wartime Tribute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'. -

Strictly Come Dancing 2020 Is an Easy and Fun Way to Help Raise Money for SNAP Jason Bell

SNAP SNAP CHARITY SWEEPSTAKE STRICTLY COME DANCING SUGGESTED 2020 DONATION Join in the fun and ensure SNAP Charity can continue to help families with children and young people who have any special need or disability TO TAKE PART CONTACT: Image:www.freepik.com Special Needs And Parents Ltd www.snapcharity.org Registered Charity No. 1077787 l A Company Limited by Guarantee in England and Wales No. 03805837 Registered Office: The SNAP Centre l Pastoral Way l Warley l Brentwood l Essex, CM14 5WF Celebrity Dancer Sweepstake Entrant Nicola Adams Clara Amfo Bill Bailey Organising a SNAP Sweepstake for Strictly Come Dancing 2020 is an easy and fun way to help raise money for SNAP Jason Bell Just follow our 4 steps to play: JJ Chalmers Print and cut out the names of the contestants 1from the bottom of this page, fold up and ask your friends or colleagues to pick a name out of a Max George hat. You could also suggest they make a donation to take part (£3). HRVY Keep a record of everyone’s chosen contestant 2 using our handy table on the right. Decide what prize you will award the winner. Jamie Laing After the Strictly Come Dancing Final, 3present the winner with their prize and make Caroline Quentin a donation to SNAP by contacting us at [email protected] or call 01277 245345. Ranvir Singh And remember... keep dancing! 4 Jacqui Smith Thank you for helping us make a difference to so many families across Essex; we really couldn’t do Maisie Smith it without the wonderful support of the community. -

Our Artist Friends

2015-2016 Our artist friends We’re incredibly lucky to have so many truly wonderful supporters and we’d really like to thank each and every one of you from the bottom of our hearts. We’re immensely grateful for everything you do for us – you make us what we are. It was thanks to the incredible support from people in the sport and entertainment industries that Sport Relief 2016 was such a success. We’re hugely grateful for their time and talent. Artists Adam Buxton Chris Waddle Five Live All Star Team Adam Riches Christian Malcolm Fred MacAulay Adnan Januzaj Christine Bleakley Freddie Flintoff Aimee Willmott Clara Amfo Gabby Logan Al Murray Clare Balding Gareth Bale Alan Davies Claudia Winkleman Gary Lineker Alan Kennedy Colin Jackson Gemma Arterton Alan Shearer Connor McNamara George Riley Alastair Campbell Craig David Geri Horner Aled Jones Dame Mary Peters Glen Durrant Alesha Dixon Damian Johnson Grace Dent Alex Jones Dan Snow Grace Mandeville Alex Reid Dan Walker Graham Norton Alice Levine Danny Cipriani Greg Davies Aliona Vilani Danny Dyer Greg James Alistair Mann Danny Jones Greig Laidlaw All Time Low Danny Mills Guy Mowbray Amelia Mandeville Danny Webber Guys and Dolls Cast Amir Khan Danny-Boy Hatchard Hal Cruttenden Anastasia Dobromyslova Darren Clarke Harrison Webb Andrea McLean Darren Gough Harry Judd Andy Fordham Dave Berry Helen Glover Andy Jordan Dave Henson Helen Pearson Andy Murray David Brailsford Howard Webb Angellica Bell David Haye Hugh Dennis Angus Deayton David James Iain Dowie Anita Rani David Kennedy Iain Stirling -

Download Pack

“THE BEST OF ALL POSSIBLE WORLDS” THE OBSERVER • WELCOME • DID YOU KNOW? Edinburgh Festival Fringe is the world’s Since opening its doors with only eight shows in 1985, largest arts festival. The Pleasance Theatre Trust better known as simply The Pleasance, has become one of the most famous festival venues in the world. It stands at the very heart of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and now spans 23 venues across 2 sites. In 2014, our 30th anniversary on the Festival Fringe, for each of the 27 days throughout the festival the Pleasance presented 240 shows from 12 different countries. We welcomed 500,000 people and sold over 420,000 tickets. The Pleasance is the first destination for anyone seeking the best shows at the Edinburgh Festival. Our year-round operation with two further theatre spaces and rehearsal room complex in central London enables those at the pinnacle of their careers alongside those just starting out, with the facilities to create and AND... develop brilliant new work. 1 in 4 tickets sold on the Fringe is for a Pleasance show. My love of the Pleasance is because it’s “ just got a great vibe. TIM MINCHIN ” • ABOUT US • As a registered charity in England, Wales and Scotland, The Pleasance Theatre Trust has created a powerful platform from which we can discover, nurture and support the best new talent from around the world. Promoters, industry experts, and festival managers from across the Globe come to the Pleasance looking for productions. The Pleasance receives no public subsidy and all revenue generated is reinvested back into future festivals and the London development programme. -

Wolverhampton & Black Country Cover

Staffordshire Cover May 2019.qxp_Staffordshire Cover 18/04/2019 12:56 Page 1 REMI HARRIS PLAYS LICHFIELD ARTS Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands BLUES & JAZZ FESTIVAL STAFFORDSHIRE WHAT’S ON MAY 2019 MAY ON WHAT’S STAFFORDSHIRE Staffordshire ISSUE 401 MAY 2019 ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On staffordshirewhatson.co.uk PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide BILL BAILEY combines musical virtuosity and stand-up at Victoria Hall TWITTER: @WHATSONSTAFFS TWITTER: @WHATSONSTAFFS YEARS & YEARS headline the Midlands’ biggest gay Pride festival FACEBOOK: @STAFFORDSHIREWHATSON FACEBOOK: NORTHERN BALLET brings Puss In Boots to The Potteries STAFFORDSHIREWHATSON.CO.UK Stafford Gatehouse Complete Full Page.qxp_Layout 1 17/04/2019 12:21 Page 1 CHECK THE WEBSITE FOR FULL LISTINGS MUSICAL THEATRE STAFFORD PRESENTS THE FULL MONTY TUES 30 APR - SAT 4 MAY @ 7.30PM THE SUMMER OF LOVE THE LITTLE MIX EXPERIENCE SAT MATINEE @ 2.30PM SUN 26 MAY @ 7.30PM TUES 28 MAY @ 6.00PM THE AMAZING ADVENTURES SING-A-LONG-A - THE ORLANDO OF PINOCCHIO GREATEST SHOWMAN TUES 28 & WED 29 MAY @ 7.30PM WED 29 MAY @ 2.30PM FRI 31 MAY @ 2.00PM & 7.00PM BOX OFFICE 01785 619080 BOOK ONLINE www.staffordgatehousetheatre.co.uk EASTGATE STREET, STAFFORD, ST16 2 LT Contents May Wolves/Shrops/Staffs.qxp_Layout 1 18/04/2019 09:10 Page 2 May 2019 Contents Flares, furs and feathers... Motown The Musical visits The Potteries - page 22 Chantel McGregor Years & Years Red By Night the list blues rock musician sure to join the party at this month’s popular after-hours event Your 16-page Lose Control at The Robin Birmingham Pride festival returns to Dudley museum week-by-week listings guide page 17 page 19 page 43 page 51 inside: 4. -

Comedy at the BBC an Introduction to Comedy Writing What to Do Next

Comedy at the BBC Ever since the BBC began broadcasting to the nation, the word ‘entertain’ has been pretty high up on the STAND-UP agenda. As the UK blinked its way out of the darkness after the Second World War, it turned to the fledgling BBC to bring a smile back to the nation’s faces. With early radio programmes such as The Goons or Hancock’s Half Hour proving to be a huge success with the nations, the stage was set for comedy writers to bring us a huge range of television comedy programmes, from sketch shows like Monty Python’s Flying Circus, French and Saunders and That Mitchell and Webb Look to shows featuring stand-up comedy Russell Howard, Kevin Bridges, Sarah Millican, Omid Djalili, Michael McIntyre such as Mock the Week, Live at the Apollo and Russell Howard’s Good News. – some of Britain’s most popular TV celebrities are stand-up comedians. An introduction to comedy writing In the Class Joker activities, look out for the funniest people in your classroom. One of the most important ways we communicate is by making each other laugh. Telling someone This style of writing can encourage them to get their best jokes down on a funny joke is brilliant for everyone: the person who hears the joke feels good, and the person who paper before turning them into a filmed performance. Does your tells it does too. We share jokes among our school friends, at home with our family and as adults in the workplace. school contain some budding stand-ups? Comedy writing is all about using words and language to make people laugh. -

We, the Undersigned, Earn Our Livelihoods from the Seafood Industry

We, the undersigned, earn our livelihoods from the seafood industry. We are essential workers and an integral part of the nation’s food security, not just during a pandemic. Fishing has been the backbone of working waterfronts and coastal communities for generations, supporting not just the families of harvesters, but also those of dealers, processors, marine suppliers, service providers, grocers, restaurants, the tourism industry, and other sectors by providing healthy and sustainable seafood to the nation. As such, we request the following be given priority as BOEM considers the approval of the first large-scale offshore wind energy area in United States waters: • All energy, including “clean energy,” has environmental impacts that must be fully understood and weighed in the context of an overall power strategy. While protecting our air and climate is important, so is protecting marine ecosystems and biodiversity. The power density of offshore wind projects is among the lowest of any energy source, and the industrialization of such large areas will permanently change marine ecosystems and threaten a strategic food supply. • The fishing industry must be included early in the planning process of any offshore development project, and long before the point that a Construction and Operations plan has been finalized. Our historic fishing locations and practices will be directly and permanently impacted by any offshore development, and every effort should be made to preserve and protect them. Any planned project will benefit from the expertise of our industry. So far, this has not occurred in any meaningful way. • Accurate and sufficient data is needed when considering where to locate offshore development projects. -

Fifa World Cup Replay 01:35 Weather for the Week Ahead 01

SATURDAY 14TH JULY All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 06:00 Breakfast 09:50 The Big Bang Theory 06:00 The Forces 500 Back-to-back Music! 10:00 Saturday Kitchen Live 10:15 The Cars That Made Britain Great 07:00 The Forces 500 Back-to-back Music! 11:30 Simply Nigella 09:25 James Martin's American Adventure 11:05 Holidays Make You Laugh Out Loud 08:00 I Dream of Jeannie 12:00 Bargain Hunt 09:55 Best Walks with a View with Julia Bradbury 11:55 Brooklyn Nine-Nine 08:30 I Dream of Jeannie 13:00 BBC News 10:20 The Best of The Voice Worldwide 12:20 Star Trek: Voyager 09:00 I Dream of Jeannie 13:15 Wimbledon 2018: Ladies' Final 11:20 The Best of The Voice Worldwide 13:00 Shortlist 09:30 I Dream of Jeannie 18:50 BBC News 12:20 ITV Lunchtime News 13:05 Modern Family 10:00 I Dream of Jeannie 19:00 BBC London News 12:30 ITV Racing: Live from Newmarket 13:30 Modern Family 10:30 Hogan's Heroes The latest news, sport and weather from 14:30 Fifa World Cup 2018: Third Place Play-off 13:55 The Fresh Prince of Bel Air 11:00 Hogan's Heroes London. 17:15 Catchphrase 14:20 The Fresh Prince of Bel Air 11:30 Hogan's Heroes 19:10 Pointless Celebrities 18:00 ITV Evening News 14:45 Ferne McCann: First Time Mum 12:00 Hogan's Heroes Celebrity edition of the quiz, with Kieran 18:15 ITV News London 15:35 Jamie and Jimmy's Friday Night Feast 12:30 Hogan's Heroes Long, Piers Taylor, Martin Roberts, Amanda 18:30 Japandemonium 16:30 Celebrity Carry On Barging 13:00 Airwolf Lamb, Vicki Butler-Henderson, Tiff Needell, 19:00 Celebrity Catchphrase 17:15 Shortlist 14:00 Goodnight Sweetheart John Hammond and Laura Tobin. -

50 Cent Abbey Clancy Adam Woodyatt Alan Carr Alan Shearer Alan

Carrie Underwood 50 Cent Cary Grant Abbey Clancy Catherine Zeta-Jones Adam Woodyatt Charlie Brooks Alan Carr Charlize Theron Alan Shearer Charles Dickens Alan Sugar Charley Webb Alesha Dixon Charlie Chaplin Alesha Dixon (Peach Dress) Chace Crawford Alexa Chung Charlie Hunnam Alice Eve Cher Lloyd Alice Eve (Purple Dress) Cheryl Cole Alison King Cheryl Cole (Pink Dress) Amanda Holden Cheryl Cole (Red Dress) Amanda Holden (White Dress) Chris Brown Amanda Seyfried Chris Evans Amanda Seyfried (Black Dress) Christopher Dean Amir Khan Claudia Schiffer Amy Adams Cliff Richard Amy Childs Colin Farrell Amy Willerton Colin Firth Andrew Scott Craig Revel Horwood Angelina Jolie Conor Maynard Anne Hathaway Dakota Johnson Ant McPartlin Daisy Lowe Antonio Banderas Daniel Craig Arnold Schwarzenegger Daniel Radcliffe Ashley Cole Dannii Minogue Audrey Hepburn (Dress) Danny Jones Avril Lavigne Danny Mac Benedict Cumberbatch Danny O'Donoghue Ben Affleck Darcey Bussell Benedict Cumberbatch (Blue Jacket) David Beckham Beyonce Knowles David Beckham (Blue Tie) Blake Lively David Gandy Bono (Shirt) David Grohl Boris Johnson David Haye Brad Pitt David Morrissey Bradley Cooper David Walliams Bruno Mars Declan Donnelly Bruno Tonioli Denzel Washington Caggie Dunlop Dermot O'Leary Calvin Harris Diane Von Furstenberg Cameron Diaz Dita Von Teese Carl Froch Dizzee Rascal Carly Rae Jepsen Dominic Cooper Donny Osmond Jake Wood Dougie Poynter James Anderson Dynamo Jamie Dornan Ed Sheeran Janet Jackson Ed Westwick Jason Orange Edward Grimes Jennifer Aniston (Black Dress) -

GO BEHIND the SCENES of RADIO with BILL BAILEY See Page 4 %Mr 411

GO BEHIND THE SCENES OF RADIO WITH BILL BAILEY See Page 4 %Mr 411. WEEK ENDING JANUARY 28, 1938 EMERY DEUTSCH MI\ VIOLINIST See Page 4 2 RADIO DIAL, WEEK ENDING JANUARY 28, 1938 New Dramatic Star Cincinnati Symphony Begins RADIO LIGHTS Brahms Cycle The Cincinnati Symphony Orches- tra this week inaugurates its widely GUESTARS OF THE WEEK: Richard Barthelmcss will be heard heralded Brahms Cycle—a special sea- on Friday, January 21. Gladys Su arthout to be interviewed son of four pairs of concerts devoted by Elza Schallert before leaving for New York where she will begin season with the Metropolitan Opera Company .. she just completed her exclusively to the major works of fourth motion picture, "Romance in thc Dark." ... Arlene Hershey, soprano, Johannes Brahms. will be soloist with the Rochester Civic Orchestra. Richard Crooks, In spacious, historic Music Hall, operatic tenor, guest soloist with "Sunday Evening Hour." .. John Smith, the Orchestra, under the baton of brilliant 15-year-old clarinetist of Port Washington, New .York, with Frank Eugene Goossens, will present, at 2:45 Simon's Armco Band. H. H. Heimann of the Department of Corn- o'clock Friday afternoon and 8:30 nterce's Business Advisory Council is guest speaker on "Story of Industry." .. Apollo Boys Choir on "Columbia Chorus Quests." .. .Duke Ellington's o'clock Saturday evening, a program orchestra and Sidney Phillips, saxophonist, guests on "Saturday Night Swing consisting of the famous "Academic Club." .. Sidney G. McAllister in a talk about industry's contribution to Festival" Overture; the Symphony the American standard of living on "Voice of Niagara." . -

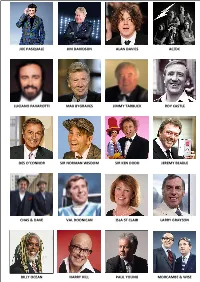

Joe Pasquale Jim Davidson Max Bygraves Jimmy Tarbuck

JOE PASQUALE JIM DAVIDSON ALAN DAVIES AC/DC LUCIANO PAVAROTTI MAX BYGRAVES JIMMY TARBUCK ROY CASTLE DES O’CONNOR SIR NORMAN WISDOM SIR KEN DODD JEREMY BEADLE CHAS & DAVE VAL DOONICAN ISLA ST CLAIR LARRY GRAYSON BILLY OCEAN HARRY HILL PAUL YOUNG MORCAMBE & WISE THE TREORCHY CHOIR ALEX HIGGINS GERRY MARSDEN DAVE DEE SUZI QUATRO RAY ALAN NORMAN COLLIER FRANK CARSON THE COMMITMENTS BOBBY KNUTT CILLA BLACK BARBARA WINDSOR DAVE BERRY FREDDIE STARR THE SUPREMES JIMMY WHITE RONNIE O’SULLIVAN STAN BOARDMAN FRANKIE VAUGHAN JIMMY GREAVES KATHY KIRBY ALVIN STARDUST THE TROGGS JASPER CARROTT BEV BEVAN THE HOLLIES MIKE YARWOOD MOTÖRHEAD SIR BOB GELDOF THE DRIFTERS ROY ‘CHUBBY’ BROWN RHOD GILBERT VICTORIA WOOD JIMMY CRICKET BERT WEEDON JOE LOSS CHUCKLE BROTHERS SOOTY DICKIE HENDERSON BOB MONKHOUSE RICK WAKEMAN MARTY WILDE THE STYLISTICS JIMMY CARR PADDY McGUINNESS MATTHEW FORD DAVE ALLEN STEVE DAVIS MARTI CAINE NEW AMEN CORNER STEVE BEATON JAKE THACKRAY DICK EMERY ED BYRNE DENNIS LOTIS FRED DIBNAH RUSSELL WATSON BILL HALEY THE PLATTERS WHITESNAKE HUMPHREY LYTTLETON BILL MAYNARD DAVID NIXON HENRY BLOFELD SHAKIN’ STEVENS SUSIE BLAKE KATE ROBBINS EDWIN STARR JET HARRIS ARTHUR BOSTROM DR FEELGOOD MICK MILLER GIANT HAYSTACKS GEORGE HAMILTON IV DEBBIE McGEE PAUL DANIELS MARTHA REEVES WENDY PETERS SHOWADDYWADDY DAVID DICKINSON ASWAD RAY QUINN THE BEVERLEY SISTERS STU FRANCIS CRISSY ROCK SIMON RATTLE TED HEATH THE ROCKIN’ BERRIES DEL SHANNON HEAVY METAL KIDS CHRIS RAMSEY BRIAN BLESSED DON MACLEAN FOSTER & ALLEN JUDAS PRIEST ERIC DELANEY PAM AYRES DAVID SHEPHERD -

Two Day Autograph Auction - Day 1 Saturday 14 July 2012 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction - Day 1 Saturday 14 July 2012 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Radisson Edwardian Heathrow Hotel 140 Bath Road Heathrow UB3 5AW International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction - Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Chariots of Fire (1981). A vintage postcard photograph showing LIDDELL ERIC: (1902-1945) Scottish Athlete & Missionary. Abrahams crossing the line at the conclusion of the 100 metre Gold medallist in the men's 400 metres at the 1924 Summer sprint final to become the Olympic Champion at the Olympic Olympics in Paris and one of the subjects of the Oscar winning Games of 1924 in Paris, signed in later years by Abrahams in film Chariots of Fire (1981). An excellent, lengthy A.L.S., Eric H. blue ink to the verso, adding the date of the race and his Liddell, three pages, 4to, Tientsin, China, 19th February 1926, winning time, 10.6 seconds, in his hand beneath his signature. to Mr. Chilvers. Liddell states that his correspondent's letter Scarce. Two very small, light stains to the verso, close to, but reached him some time ago and hopes that he hasn't left it too not affecting, the signature, otherwise VG long before replying, continuing 'I find it a bit difficult to know Estimate: £100.00 - £120.00 what to start with as I do not know what opportunity you get for practising…The simplest way will be by numbering the various points. (1) Remember warmth is one of the things that all sprint Lot: 3 athletes need.