The Master Teacher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

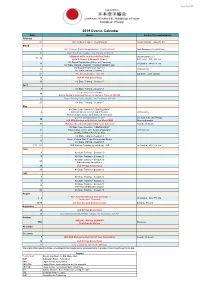

2019 Events Calendar

Issue: April 2019 2019 Events Calendar Date Event Contact Person/Location February 24 VKL Melbourne Open – Keysborough Rosanna Kassis – 0402 278 531 March 3 ** AKF Victorian State Championships – Wantirna South ** Aash Dickinson – 0488 020 822 11 Labour Day Public Holiday - No Training at JKA NP SEMINAR WITH JKA HQ INSTRUCTORS JKA SKC Melbourne 11 - 12 Naka T. Sensei & Okuma K. Sensei Keith Geyer - 0407 886 764 KV Squad Registration (Kata)– VU Footscray 16 Ian Basckin – 0410 778 510 KV State Training – Session 1 Kumite Evaluation Day KV Squad Registration (Kumite) 23 VU Footscray KV State Training – Session 2 24 VKL Shotokan Open – Box Hill Edji Zenel – 0438 440 555 29 JKA NP Kyu Grade Exam 30 KV State Training – Session 3 April 6 KV State Training – Session 4 Good Friday Public Holiday 19 Senior Grade training will be on, no General Class at JKA NP 22 Easter Monday Public Holiday - No Training at JKA NP 27 KV State Training – Session 5 May KV State Team Selection *COMPULSORY* 4 Kata (Children 8 to 13 yr. old & Teams) VU Footscray Kumite (Cadet, Junior, U21, Senior & Veterans) Queen's Birthday Public Holiday 5 to 8 pm at the JKA NP Dojo 10 JKA KDA Seminar with Shihan Jim Wood MBE Open to all grades 11 JKA Aus. Oceania Championship Team Selection Rowville, Melbourne KV State Team Selection *COMPULSORY* 11 Kata (Cadet, Junior, U21, Senior & Veterans) VU Footscray Kumite (Children 9 to 13 yr. old) 18 KV State Training – Session 8 Karate Victoria State Team Presentation Dinner 25 KV State Training – Session 9 31/5 – 2/6 AKF National Training -

Student(Handbook(

Arizona(JKA 6326(N.(7th(Street,(Phoenix,(AZ(85012( Phone:(602?274?1136( www.arizonajka.org www.arizonakarate.com( ! [email protected]( ! Student(Handbook( ! ! What to Expect When You Start Training The Arizona JKA is a traditional Japanese Karate Dojo (school). Starting any new activity can be a little intimidating. This handbook explains many of the things you need to know, and our senior students will be happy to assist you and answer any questions you might have. You don’t have to go it alone! To ease your transition, here are some of the things you can expect when you start training at our Dojo: Class Times Allow plenty of time to change into your gi, or karate uniform. Men and women’s changing rooms and showers are provided. You should also allow time to stretch a little before class starts. Try to arrive 15 minutes before your class begins. If your work schedule does not allow you to arrive that early, explain your situation to one of the senior students. There is no limit to the number of classes you can attend each week, but we recommend training at least 3 times a week if at all possible, to gain the greatest benefit from your karate training. Morning Class: 11:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon Monday, Wednesday, Friday Adult class, where all belt levels are welcome. Afternoon Class: 5:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. Monday, Wednesday, Friday All ages and belt levels are welcome. This class has multiple instructors and is ideal for the beginning student. -

LION December 2019

The Lion ! The official magazine of the Chiltern Karate Association December 2019 Takuya Taniyama 1965 - present Foreword…. Osu! Welcome to the December 2019 edition of The Lion! The front-page features another of giants of Shotokan karate – Takuya Taniyama Sensei. Born in 1965, he was a student of Takushoku university. At the age of 25 yrs old he graduated from the JKA Instructors course and became a full-time Honbu dojo instructor. A kumite specialist, he won the all Japan Karate Championships for kata in 1995, 1996, 1998 and 2001 and then decided to concentrate on kata. And then something extraordinary happened…. Taniyama entered the kumite competition of the 50th JKA championships, and at the relatively (in elite competition terms) of 42 years old….he won! Members of the CKA were fortunate to train with Taniyama Sensei in Tokyo in 2018, at the Takushoku University. My heartfelt thanks to you all for the support you have shown myself & the CKA during 2019. Without the commitment of you, the students, the CKA could not continue to thrive & flourish. 2020 looks set to be a bumper year for the CKA, with many guest instructors in the pipeline, access to external competitions and, of course, the annual BBQ! Good luck to everyone grading today! D C Davenport Dave Davenport Chief Instructor - 6th Dan EKF CKA Dan Examination – September 2019 Ometedō gozaimasu ! • Olivier Javaud – Nidan • Alex Ramsay – Sandan • Paul Massey – Sandan We expect further progress in skill and character building in the future…. Shihankai Promotions – September 2019 Ometedō gozaimasu ! • Bernard Murray – Yondan • Michael Thornton – Yondan One of the changes we have recently made was to Dan Gradings. -

Japan Karate Association of India, Karnataka

+ JAPAN KARATE ASSOCIATION OF INDIA, KARNATAKA Affiliated to : Japan Karate Association (JKA) Japan Karate Federation (JKF), Member of Akila Karnataka Sports Karate Association (AKSKA Karate Association of India (KAI) Asian Karate Federation (AKF), South Asia Karate Federation (SAKF), World Karate Federation (WKF) Recognized by : Indian Olympic Association, International Olympic, Committee & Govt. of India (Ministry of Sports & Youth Affairs) SENSEI R. ASHMITHA APARNA 2nd Dan Black Belt joint treasurer JKA India, Karnataka D/o. Raghu.R #49 ,2nd cross Narallappa layout Gudadhahalli V nagenahalli main road. RT nagar post Bengaluru 560032 Mobile No: 9880074760 E -Mail: [email protected] Objective: Professional advancement in the field of Karate and Self Defense, with a leading establishment and World’s largest; most prestigious karate organization. JKA is Dynamic intuition specialized in new and intelligent philosophy of karate. Professional Summary: Learning karate from past 15 years. A competent Karate Trainer with having more than 4 years of experience in SHOTOKAN KARATE in India. Teaching; conducting karate camps, seminars, state and national tournaments spatial training to all the school, college students, ladies and private institution. Professional Profile: 2nd DAN Black belt, have been undergone varies skilled training and certified national instructor, coach, examiner. And certified Trainer of, JKA Karnataka instructor licensed from Japan, and JKAI National kata, Kumite champion. Professional Training: • 2nd Dan Black Belt WATK Approved by: all India karate-do federation, recognized by: Ministry of Youth Affairs & Sports, Indian Olympic Association. • Participated in National Karate Championship Organized by: Karate Association of India • Participated in the 10th JKA All India Training Camp, on Instructor’s training. -

History of Shotokan Karate

History of Shotokan Karate An accurate, well documented, history of Shotokan karate is difficult to establish due to the decimation of Okinawa during World War II. Most of the documented history we have today has been passed down through word of mouth or substantiated using secondary documentation. However, there are four common theories addressing the development of karate, they are: • Karate developed from unarmed fighting traditions developed by the Okinawan peasantry. • Karate was primarily influenced by the Chinese fighting arts. • Due to the ban of weapons instituted in 1507 by the Okinawan king Sho Shin, wealthy Okinawans had a need to defend their property. • Karate was developed by Okinawan law enforcement and security personnel after Satsuma invaded Okinawa in 1609 and banned all weapons. It’s most likely, however, that each of the above influenced the development of Shotokan karate. Early development can be traced back to Chinese fighting arts. The most popular being Gonfu (kunfu). Of all the Gonfu styles that may have influenced our Shotokan karate, it seems that White Crane gonfu, developed by Fang Qiniang, a young girl who grew up in Yongchun, China, appears to have had the greatest influence on the development of modern day karate. Master Funakoshi believed that karate developed as an indigenous Okinawan martial art. Satunushi “Tode” Sakugawa was the first teacher in the Shotokan lineage who made specific contributions to the karate we study today. Though his techniques were primarily based on White Crane Chuan Fa, Sakugawa is credited with developing Kusanku kata, the basis for our Kankudai and Kankusho katas, the first set of dojo kun, and the concept of “hikite”, opposite or pullback hand. -

Fall Edition.Qxp

ISKF SPOTLIGHT Fall 2008 INTERNATIONAL SHOTOKAN KARATE FEDERATION aster Camp 2008 was a truly memo- MASTER CAMP 2008 - rable year - those who attended were INTERNATIONAL CELEBRATION fortunate enough to train with four of the OF SHOTOKAN KARATE Mmost skilled karate masters the world has ever known - Masters Teruyuki Okazaki 10th dan and Yutaka Yaguchi 9th dan of the ISKF, and Masters Hirokazu Kanazawa 10th dan and Masaru Miura 9th dan of the SKIF. We were first introduced to Master Kanazawa and his karate training methods and philosophy at Master Camp 2007. History was made at last year's Camp when the final vote was cast, officially declaring the International Shotokan Karate Federation (ISKF) independent from the Japan Karate Association (JKA). Already after only one year we can see the doors of opportunity opening and are experiencing some of the joys of our newly found freedom. Since our independence last year (June 2007) many countries have contacted us wanting to join the ISKF. These countries want to be part of a democratic organization and many have experienced problems with Master H. Kanazawa, left - Master T. Okazaki, middle - Mr. B. Sandler, right photos by Thomas Cote, ISKF Quebec, Canada the JKA. The ISKF constitution requires that we do things in a demo- Iran, and Georgia. Dojo and Nijyu Kun. These are cratic way. We discuss issues and The ISKF follows the principles of karate's guiding principles and are take the majority vote on what to do. our founder, Master Gichin Funakoshi. meant to be remembered and fol- We have already welcomed nine new Master Funakoshi was a visionary of lowed by all karate-ka. -

A Short History of Shotokan Karate Karate's Origins Can Be Traced Back

A Short History of Shotokan Karate Karate’s origins can be traced back to the earliest instances of human civilization. The history of karate that is taught at Harambee Karate Club begins with the Indian Monk Bodhidharma who arrived in China sometime in the late fifth or early sixth century. After several years travel in the country he sensed that most practitioners of Buddhism in China were failing to grasp its central tenets. He settled in a cave across from the Shaolin monastery in Henan Province to show by practical demonstration the “correct” way to achieve what was so often easily misunderstood. Discovering that the monks did not have the necessary stamina to endure the physical and spiritual stresses his type of meditation required, he began instructing them in a method of conditioning that would come to be called Shorinji Kempo. Later on China replaced its civilian envoys to Okinawa with military personnel who were skilled in the arts of Chinese Kempo. Changes in the political leadership in the Ryukyu Island chain and subsequent changes in the relationship between Japan and the Ryukyus led local ch’uan fa groups and tode societies to band together in 1629 to form a united front. Out of this union came Okinawa-te that is a lineal ancestor of what we practice today called Shotokan Karate-Do. As it was fundamentally a combat art Okinawa-te was learned and practiced in secret. Indeed it was not until the end of Satsuma rule in 1875 with the Meiji Restoration that the three major styles, Naha, Shuri and Tomari named after in the cities in which they were located became visible. -

Gichin Funakoshi Founder of Shotokan Karate

" The ultimate aim of the art of Karate lies not in victory or defeat, but in the perfection of character of its participants." Gichin Funakoshi Founder of Shotokan Karate BENEFITS OF SHOTOKAN KARATE: Builds self-esteem Enhances flexibility Improves coordination & balance Maximizes cardio-respiratory fitness Promotes discipline Teaches self defense What is Shotokan Karate? Karate means "empty (Kara) hand(tae)", and Karate-do translates to "the way of Karate". Shotokan Karate is a weaponless martial art that is founded on the basic techniques of punching, striking, kicking and blocking, yet there is a deeper aspect to serious Karate training which deals with character development. Shotokan Karate is a way for an individual to realize greater potential and expand the limits of that individual's physical and mental capabilities. Karate in an excellent, time- proven method of personal development. Shotokan Karate is a traditional Japanese Martial Art founded by Master Gichin Funakoshi. Shotokan Karate remains firmly rooted in a strong martial arts tradition, emphasizing lifetime training for a healthy mind and body, rather than strictly as a sport. History: Shotokan (松濤館 Shōtōkan?) is a style of karate, developed from various martial arts by Gichin Funakoshi (1868–1957) and his son Gigo (Yoshitaka) Funakoshi (1906–1945). Gichin was born in Okinawa and is widely credited with popularizing "karate do" through a series of public demonstrations, and by promoting the development of university karate clubs, including those at Keio, Waseda, Hitotsubashi (Shodai), Takushoku, Chuo, Gakushuin, and Hosei. Funakoshi had many students at the university clubs and outside dojos, who continued to teach karate after his death in 1957. -

Master Gichin Funakoshi (1868 - 1957)

Master Gichin Funakoshi (1868 - 1957) Shotokan is a style of karate, developed from various martial arts by Gichin Funakoshi and his son Gigo (Yoshitaka) Funakoshi. Gichin was born in Shuri, Okinawa and is widely credited with popularizing karate through a series of public demonstrations, and by promoting the development of university karate clubs, including those at Keio, Waseda, Hitotsubashi (Shodai), Takushoku, Chuo, Gakushuin, and Hosei. As a boy, he was trained by two famous masters of that time. Each trained him in a different Okinawan martial art. From Yasutsune Azato he learned Shuri-te. From Yasutsune Itosu, he learned Naha-te. It would be the melding of these two styles that would one day become Shotokan karate. Funakoshi had many students at the university clubs and outside dojos, who continued to teach karate after his death in 1957. However, internal disagreements (in particular the notion that competition is contrary to the essence of karate) led to the creation of different organizations— including an initial split between the Japan Karate Association (headed by Masatoshi Nakayama) and the Shotokai (headed by Motonobu Hironishi and Shigeru Egami), followed by many others— so that today there is no single "Shotokan school", although they all bear Funakoshi's influence. Shotokan was the name of the first official dojo built by Funakoshi, in 1939 at Mejiro, and destroyed in 1945 as a result of an allied bombing. Shoto, meaning "pine-waves" (the movement of pine needles when the wind blows through them), was Funakoshi’s pen-name, which he used in his poetic and philosophical writings and messages to his students. -

Karate History

Origin of Shotokan Karate Shotokan translates literally into —the hall of Shoto“. Shoto was the pen name of Gichin Funakoshi, the karate master responsible for popularizing karate in Japan. This —hall“ was the world‘s first free standing karate dojo built for Funakoshi by his students in 1936. In 1868, Gichin Funakoshi was born in Okinawa into a privileged class known as the shizoku. Okinawa is the largest island in a chain of more than 60 small islands found south of the mainland of Japan. Funakoshi was a premature baby which was an omen of ill health in Okinawa at that time. As was customary with children born prematurely, he was raised by his maternal grandmother who could provide him with the additional nurturing he required. Funakoshi‘s doctor recommended that he train with the karate master Azato in the hopes that it would improve the child‘s health. Azato accepted the young pupil and Funakoshi began the physical regimen which he later came to believe blessed him with good health for all of his 89 years. Azato advocated strict physical and mental discipline for all of his students; he believed that both were necessary for proper growth and development. Azato encouraged Funakoshi‘s studies of the Chinese Classics and the Confucian Dialects that were required of a son of the shizoku class. In 1888, Funakoshi passed the necessary tests qualifying him as an education teacher. He commenced a 30 year teaching career in Okinawa‘s primary, middle, and upper level schools. Throughout this period Funakoshi continued his karate training daily, making a nightly pilgrimage to the home of Azato. -

Istoria-“JKA”, Şi Şcolilor De Karate Shotokan Derivate Din

Istoria-“JKA”, şi şcolilor de Karate Shotokan derivate din JKA Era Pre-Razboi ,o mica istorie.In anul 1922 -Okinawan Karate prin persoana Maestrului Gichin Funakoshi demonstreaza “TO-DE”in Ochanomizu,pentru Ministerului Educatiei din Japonia.In anul 1929 -In urma discutiilor cu Gyodo Furukawa(preot sef la Templul Enkaku, Kamakura) Funakoshi vazand asemanarile dintre filozofia ZEN si KARATE,dezvolta “spiritual de Karate”si schimba “TO-DE” în “KARATE”. In anul 1930- Era Razboi ,Masatoshi Nakayama si Masatomo Takagi au pastrat vie practica de Karate,dezvoltand-o aceasta în mod oficial. Funakoshi Shotokan Hombu Dojo a fost distrus în urma unui raid aerian de o bomba.In anul 1949 - Era Dupa-Razboi. Se fondeaza si are recunoaste provizorie în mod oficial (The JAPAN KARATE ASSOCIATION),Asociatia Japoneza de Karate prin intermediul lui Yoshinosuke Saigo(membru al Casei de Consiliu,a Guvernului Japonez).In anul 1953 -prin intermediul lui Tsutomu Oshima ,Hidetaka Nishiyama ” are acum 10 Dan conduce I.T.K.F.” primeste invitatie sa predea la Strategic Air Command (USA) Comandamentul Strategic Aerian American astfel introducand Karate în SUA-America,care este acum o arta Internationala. In anul 1955 - Funakoshi Sensei are 86 de ani, Takagi poarta conversatie si face planuri cu un producator de film Yuzuru Kataoka,pentru mediatizarea prin film a stilului Shotokan,si a noului Hombu Dojo.La sfarsitul anului Yuzuru Kataoka, îl suna pe Takagi ca sa afle despre ultimele stiri legate despre noul dojo,aceasta este centrul de baza în dezvoltare a JKA.In anul 1956 -Instructorii pregatitori dezvolta prin Nakayama Sensei si Nishiyama Sensei directia pe care se vor crea legendele de maine ale JKA. -

Fma-Special-Edition PKA.Pdf

Publisher Steven K. Dowd Contributing Writers Emmanuel ES Querubin Contents From the Publishers Desk Karate in the Philippines - The Golden Years Philippine Karate Association - Culmination of the Dream Council of Administrators 1st (Philippines) World Invitational Karate Tournament and Goodwill Matches PKA Official Tournament Rules Unknown Pillars of Karate in the Philippines Latino Gonzales "Grand Old Man" Karate Code of Conduct Filipino Martial Arts Digest is published and distributed by: FMAdigest 1297 Eider Circle Fallon, Nevada 89406 Visit us on the World Wide Web: www.fmadigest.com The FMAdigest is published quarterly. Each issue features practitioners of martial arts and other internal arts of the Philippines. Other features include historical, theoretical and technical articles; reflections, Filipino martial arts, healing arts and other related subjects. The ideas and opinions expressed in this digest are those of the authors or instructors being interviewed and are not necessarily the views of the publisher or editor. We solicit comments and/or suggestions. Articles are also welcome. The authors and publisher of this digest are not responsible for any injury, which may result from following the instructions contained in the digest. Before embarking on any of the physical activates described in the digest, the reader should consult his or her physician for advice regarding their individual suitability for performing such activity. From the Publishers Desk Kumusta This Special Edition brings back some memories when KARATE was the word in the Philippines and thought it would be very interesting for you the reader. Many thanks to Emmanuel ES Querubin for he contributed almost all the information and definitely pictures for this Special Edition.