Consuming Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reptile Lighting Information by DR

Reptile Magazine 2009 Reptile Lighting Information BY DR. FRANCES M. BAINES, MA, VETMB, MRCVS To reptiles, sunlight is life. Reptiles are quite literally solar powered; every aspect of their lives is governed by their daily experience of solar light and heat, or the artificial equivalent when they are housed indoors. Careful provision of lighting is essential for a healthy reptile in captivity. Infrared and Visible Light Effects on Reptiles The spectrum of sunlight includes infrared, “visible light” (the colors we see in the rainbow) and ultraviolet light, which is subdivided into UVA, UVB and UVC. Very short wavelength light from the sun (UVC and short wavelength UVB) is hazardous to animal skin and eyes, and the atmosphere blocks it. Natural sunlight extends from about 290 to 295 nanometers, which is in the UVB range, to more than 5,000 nanometers, which is in the long-wavelength infrared (heat) range. Infrared light is the sun’s warmth, and basking reptiles absorb infrared radiation extremely effectively through their skin. This part of the light spectrum is invisible to humans and most reptiles, but some snakes can perceive the longer wavelengths (above 5,000 nanometers) through their facial pit organs. Ceramic heaters and heat mats emit only infrared. Incandescent lamps emit infrared and visible light. Some incandescent red basking lamps are described as “infrared” lamps, but these also emit red visible light. Visible light, including UVA, is essential. Many reptiles have extremely good color vision. Humans have three types of retinal cone cells for color vision, and their brains combine the information from these cells and perceive the blend as a certain color. -

The Risks and Benefits of Cutaneous Sunlight Exposure Sarah Jane Felton

The Risks and Benefits of Cutaneous Sunlight Exposure A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Medicine in the Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health 2016 Sarah Jane Felton School of Biological Sciences Division of Musculoskeletal & Dermatological Sciences 2 CONTENTS List of contents......................................................................................................................................... 3 List of figures ............................................................................................................................................ 8 List of tables ............................................................................................................................................10 List of abbreviations ............................................................................................................................11 Abstract ....................................................................................................................................................15 Declaration ..............................................................................................................................................16 Copyright statement ...........................................................................................................................17 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................18 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION -

Is Tanning Related to Need for Acceptance? Erica Bewley, Natalie

Running head: The Need for Acceptance and Tanning 1 Is Tanning Related to Need for Acceptance? Erica Bewley, Natalie Kent, and Emilee Roberts Hanover College PSY 220: Research Design and Statistics Winter 2012 The Need for Acceptance and Tanning 2 Abstract This study was designed to examine the relationship between tanning and the need for acceptance. 76 participants (56 females and 20 males) were randomly sampled to complete an online questionnaire sent via email. The questionnaire was designed to measure each participant’s need for acceptance, attitudes toward tanning, and tanning behaviors. There was a significant positive correlation between attitudes toward tanning and scores on the need for acceptance scale, r(76) = +0.43, p < .001, indicating that people with attitudes more in favor of tanning scored higher on the need for acceptance scale. In addition, women scored significantly higher on the need for acceptance scale than men, t(33.39) = 2.35, p < 0.025. On average, females scored 2.50, while men scored 2.12. The 95% confidence interval for the effect of gender on scores on the need for acceptance scale is between 0.05 and 0.7 points. The Need for Acceptance and Tanning 3 Is Tanning Related to Need for Acceptance? Tanning is the act of going to an indoor tanning salon, laying outside, or using lotion in order to increase the pigmentation of your skin to make appear darker. Indoor tanning salons consist of tanning beds, which contain UV lights that serve as artificial sunlight in order to create a tan. Outdoor tanning would obviously result in color from the natural sun, and spray tanning coats the skin with a layer of dark color. -

Pdf Prikaz / Ispis

Utopia and Political Theology No. 2 - Year 5 06/2015 - LT.6 Zoran Ferić - Tomislav Kuzmanović, University of Zadar, Croatia Alone by the Sea 1. At first the island is just a sign on a yellow board with a drawing of a vessel and the letters saying “Car Ferry,” then it is a grayish silhouette in the blue of the sea, and then, later still, an acquaintance working on the ferry, who just nods briefly in greeting. Jablanac, ferry port, its pleasant lobby, and then, from the upper deck, a giant rock approaching. That is the object of a year-long desire: the moment of stepping off the boat and smelling the rosemary, diesel and sheep droppings, seeing the sharp rocks looking at the Strait of Senj, coarse limestone in sharp opposition to the signs that say: Benvenuti, Welcome, Willkommen! At home, on the terrace, in the shade of the oleander, there’s no wish to eat. Only swimming trunks are put on and then, barefoot, without a towel or sun-tanning lotion, off to the beach. “Why won’t you eat something?” grandma asks. She knows that there’s an exciting world waiting out there, but she knows nothing of the details. All friends went on a boat trip. And suddenly one step from the shade of a path covered with oleanders and acacias leads into the burning sun of the afternoon. The light screams, just like children in the water, just like white objects that radiate as if there are some powerful light bulbs within. The feeling of freedom of someone who has just arrived in a foreign place and can now do anything. -

Spa-Broschuere-1521556030.Pdf

REJUVENATE YOUR SENSES Dear Valued Guest, I would like to personally welcome you to the Myconian Collection Spas. All of our 7 Spas are a magical place of relax- ation and of nursing mind, body and soul. We aim to offer you a personal journey that is dedicate to revitalising your body, mind and soul. With a carefully curated menu, inspired by the purest resources from oceans and earth, to allow you to experience the wonders of well-being with methods ascertained since antiquity up to nowadays. Your skin and your well-being lies at the heart of what we do and we have joined forces with ELEMIS, one of the world’s leading and premium SPA brands, as well as St.Barths with products of exceptional quality. Our treatments are designed to respect the body’s complex physiology, and to work in natural synergy with the skin, body and mind. Every treatment is specifically designed to offer a unique experience, using powerful massage sequenc- es and the most potent actives available in the world today. Our highly trained therapists make it personal. They look, they listen, tune in to you. Our secret dwells in the wealth of the sea, the extracts of plants, flowers and botanicals and to the expert teqhnique we apply for every therapy. Transformative results. Unique Experiences. Welcome to the Myconian Spas. Eleftheria Karapiperaki Director of Spas at Myconian Collection MYCONIAN VILLA COLLECTION SIGNATURE TREATMENTS Myconian Signature Escape 1hr 20mins This treatment is designed to hydrate and nourish your skin. Body Wrap & Relaxing Full body Massage Express Facial Treatment Myconian Signature Journey 1hour 50mins An interactive experiment of the senses. -

Radiation Distribution Uniformization by Optimized Halogen Lamps Arrangement for a Solar Simulator

Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Rabat, Morocco, April 11-13, 2017 Radiation distribution uniformization by optimized halogen lamps arrangement for a solar simulator Hazim Moria Department of Mechanical Engineering Technology,Yanbu Industrial College, Yanbu Al-Sinaiyah 41912, KSA E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract Solar simulator plays a vital role in the research and development of solar photovoltaic, solar thermal and builds environment. Producing uniformity in spatial, temporal and spectral radiation distribution are the key parameters when developing a solar simulator so the sun radiation is matched as closely as possible in the laboratory environment. This paper presents a development of a solar simulator for education and research purpose. The objective is to achieve a uniform spatial distribution of radiation from a set of halogen lamps. The simulator was built with eight 500W halogen lamps powered by typical domestic 220 V source. The lamps are connected in two parallel four-in-series arrangement and placed perpendicularly from each other about halogen bulb axis. The distance between lamp reflectors edge was varied and total radiation measured by a pyranometer at various distance from the lamp. The findings showed that the optimal distance between reflector edges is 0.15 m which produced good spatially uniform radiation between 500 and 1100 W/m2 at distance between 0.20 and 0.40 cm within the test area of 0.4 m2. Keywords: Irradiance; solar photovoltaic; solar thermal; indoor testing; 1. Introduction Utilization of solar energy in its optimized form is the ultimate solution for energy crisis. -

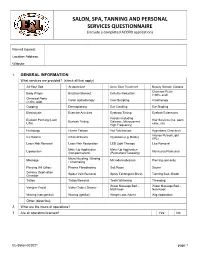

SALON, SPA, TANNING and PERSONAL SERVICES QUESTIONNAIRE (Include a Completed ACORD Application)

SALON, SPA, TANNING AND PERSONAL SERVICES QUESTIONNAIRE (include a completed ACORD application) Named Insured: Location Address: Website: 1. GENERAL INFORMATION What services are provided? (check all that apply) 24-Hour Spa Acupuncture Acne Scar Treatment Beauty School/ Classes Chemical Peels Body Wraps Brazilian Blowout Cellulite Reduction (<30% acid) Chemical Peels Colon Hydrotherapy Cool Sculpting Cryotherapy (>30% acid) Cupping Dermaplaning Ear Candling Ear Stapling Electrolysis Exercise Activities Eyebrow Tinting Eyelash Extensions Facials (including Eyelash Perming (Lash Hair Services (cut, perm, Eyelash Tinting Galvanic, Microcurrent, Lifts) color, etc) High Frequency) Herbology Henna Tattoos Hot Tub/Jacuzzi Hyperbaric Chambers Intense Pulsed Light Ice Rooms Infrared Sauna Injections (e.g. Botox) (IPL) Laser Hair Removal Laser Hair Restoration LED Light Therapy Lice Removal Make-Up Application Make-Up Application Liposuction Manicures/Pedicures (non-permanent) (Permanent/Tattooing) Micro Needling / Blading Massage Microdermabrasion Piercing (ear only) / Channeling Piercing (All Other) Plasma Fibroblasting Salt Room Sauna Sensory Deprivation Spider Vein Removal Spray Tanning/Air Brush Tanning Bed / Booth Chamber Tattoo Tattoo Removal Teeth Whitening Threading Water Massage Bed – Water Massage Bed – Vampire Facial Vichy (Table) Shower Mall Kiosk Non Kiosk Waxing (non-genital) Waxing (genital) Weight Loss Advice Wig Application Other (describe): 2. What are the hours of operations? 3. Are all operators licensed? Yes No EL-Salon-022021 page 1 HAIR, SKIN, AND NAIL SERVICES N/A 1. Provide the total number of all operators (include employees, owners, independent contractors or others providing services) Full Time Part Time Full Time Part Time Employee Type (20+ hrs/ (<20 hrs/ Employee Type (20+ hrs/ (<20 hrs/ week) week) week) week) Beauticians/Barbers Aesthetician Nail Technicians Massage Therapists Electrologists (include those Other (describe): performing chemical peels & microdermabrasion) 2. -

Print This Article

Cómo referenciar este artículo / How to reference this article Németh, A., & Pukánszky, B. (2020). Life reform, educational reform and reform pedagogy from the turn of the century up until 1945 in Hungary. Espacio, Tiempo y Educación, 7(2), pp. 157-176. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14516/ete.284 Life reform, educational reform and reform pedagogy from the turn of the century up until 1945 in Hungary András Németh email: [email protected] Eötvös Loránd University. Hungary / János Selye University Komárno. Slovakia Béla Pukánszky email: [email protected] University Szeged. Hungary / János Selye University Komárno. Slovakia Abstract: Since the end of the 19th century, the modernisation processes of urbanisation and industrialisation taking place in Europe and the transatlantic regions have changed not only the natural environment but also social and geographical relations. The emergence of modern states changed the traditional societies, lifestyles and private lives of individuals and social groups. It is also characteristic of this period that social reform movements appeared in large numbers – as a «counterweight» to unprecedented, rapid and profound changes. Some of these movements sought to achieve the necessary changes with the help of individual self-reform. Life reform in the narrower sense refers to this type of reform movement. New historical pedagogical research shows that in the major school concepts of reform pedagogy a relatively close connection with life reform is discernible. Reform pedagogy is linked to life reform – and vice versa. Numerous sociotopes of life reform had their own schools, because how better to contribute than through education to the ideal reproduction and continuity of one’s own group. -

To Tan Or Not to Tan? Here Are the Facts!

TO TAN OR NOT TO TAN? HERE ARE THE FACTS! WHO GETS SKIN CANCER? WHAT ARE THE FACTS ABOUT Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States. TANNING AND TANNING BEDS? It affects men and women, oungy and old. Over 90 percent of • Persons who first use tanning beds before the age of 35 skin cancers are caused by exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light, increase their risk of melanoma by 75 percent. the same type of light that makes people tan. Skin cancer can be prevented by taking a few safety measures, such • Tanning beds are in the same cancer risk category as as wearing sunscreen, staying in the shade AND avoiding arsenic, tobacco smoke, the hepatitis B virus and artificial sources of UV light, such as tanning beds. radioactive plutonium. • There is no such thing as a “safe tan.” A base tan does WHAT IS SKIN CANCER? not protect from sunburn. In fact, a tan is the body’s natural response to UV rays and indicates that the skin Melanomas and nonmelanomas are the two categories of has been damaged. skin cancer. • Tanning beds use the same UV light as sunlight. Nonmelanomas (usually called basal cell and squamous cell Just 20 minutes in a tanning booth is the same as cancers) are the most common cancers of the skin. They are spending an entire day at the beach. also the easiest to treat if found early. These cancers are more common in older people. • UV rays break down the elasticity of the skin, causing premature aging, fine lines and wrinkles. -

Ultraviolet Radiation

Environmental Health Criteria 160 Ultraviolet Radiation An Authoritative Scientific Review of Environmental and Health Effects of UV, with Reference to Global Ozone Layer Depletion V\JflVV ptiflcti1p cii ii, L?flUctd EnrrcmH Prormwe. Me World Haah6 Orgniri1ion and Fhc nIrrHbccrlT Ornrn)is5ion on Nfl-oflizirig Raditiori Prioiioii THE Ef4VIRONMEF4FAL HEALTH CI4ITERIA SERIES Acetonitrile (No. 154, 1993) 2,4-Dichloroplierioxyaceric acid (2 4 D) (No 29 Acrolein (No 127, 1991) 1984) Acrylamide (No 49, 1985) 2,4.Dichlorophenoxyucetic acd - erivirorrmerrtul Acr5lonilrile (No. 28, 1983) aspects (No. 54, 1989) Aged population, principles for evaluating the 1 ,3-Dichloroproperte, 1,2-dichloropropane and effects of chemicals (No 144, 1992) mixtures (No. 146, 1993( Aldicarb (No 121, 1991) DDT and its derivatives (No 9 1979) Aidrin and dieldrin (No 91 1989) DDT and its derivatives - environmental aspects Allethrins (No 87, 1989) (No. 83, 1989) Alpha-cypermethrirr (No 142, 1992) Deltamethrin (No 97, 1990) Ammonia (No 54, 1985) Diamirrotoluenes (No 74, 1987( Arsenic (No 18. 1981) Dichiorsos (No. 79, 1988) Asbestos and other natural mineral fibres Diethylhexyl phthalate (No. 131, 191112) (No. 53, 198€) Dirnethoate (No 90, 1989) Barium (No. 137 1990) Dimethylformnmde (No 114, 1991) Benomy( (No 143, 1993) Dimethyf sulfate (No. 48. 1985) Benzene (No 150, 1993) Diseases of suspected chemical etiology and Beryllium (No 106, 1990( their prevention principles of studies on Biommkers and risk assessment concepts (No. 72 1967) and principles (No. 155, 1993) Dilhiocarbsmats pesticides, ethylerrvthiourea, and Biotoxins, aquatic (marine and freshmaterl propylerrethiourea a general introdUCtiori (No 37, 1984) NO. 78. 1958) Butanols . four isomers (No. 65 1987) Electromagnetic Fields (No 1 '37 19921 Cadmiurrr (No 134 1992) Endosulfan (No 40. -

KATALOG 12 Versandantiquariat Hans-Jürgen Lange Lerchenkamp

KATALOG 12 Versandantiquariat Hans-Jürgen Lange Lerchenkamp 7a D-29323 Wietze Tel.: 05146-986038 Email: [email protected] Bestellungen werden streng nach Eingang bearbeitet. Versandkosten (u. AGB) siehe letzte Katalogseite. Alchemie u. Alte Rosenkreuzer 1-45 Astrologie 46-77 Freimaurer, Templer u.a. Geheimbünde 78-104 Grenzwissenschaften 105-163 Heilkunde u. Ernährung 164-190 Hypnose, Suggestion u. Magnetismus 191-214 Lebensreform, völkische Bewegungen u. Ariosophie 215-301 Okkultismus u. Magie 302-363 Spiritismus u. Parapsychologie 364-414 Theosophie u. Anthroposophie 415-455 Utopie u. Phantastik 456-507 Volkskunde, Aberglaube u. Zauberei 508-530 Varia 531-666 Weitere Angebote - sowie PDF-Download dieses Katalogs (mit Farbabbildungen) - unter www.antiquariatlange.de . Wir sind stets am Ankauf antiquarischer Bücher aller Gebiete der Grenz- und Geheimwissenschaften interessiert! Gedruckt in 440 Exemplaren. Ein Teil der Auflage wurde mit einem Umschlag Liebe Kunden, die Bücher in unseren Katalogen sind Exklusivangebote . Das heisst, sie werden zunächst nur hier im Katalog angeboten! Erst etwa ein/zwei Monate nach Erscheinen des Katalogs, stellen wir die unverkauften Bücher auch online (Homepage, ZVAB & Co.). 2 – www.antiquariatlange.de Alchemie und Alte Rosenkreuzer 1. [Sod riqqavon we-serefa] i.e. Das Geheimnuß der Verwesung und Verbrennung aller Dinge, nach seinen Wundern im Reich der Natur und Gnade, Macro Et Microcosmice, als die Schlüssel: Dadurch der Weeg zur Verbesserung eröffnet, das verborgene der Creaturen entdecket, und die Verklärung des sterblichen Leibes gründlich erkant wird [...]. Dritte und mit vielen curiösen Obersvationibus vermehrte Auflage. (3. verm. Aufl.) Franckfurt am Mayn, In der Fleischerischen Buchhandlung, 1759. 109 S., Kl.-8°, Pappband d. Zt. 1000,00 € Caillet 6743; Ferguson I,306 u. -

5. Physical Therapies

70 Health guidelines for personal care and body art industries 5. Physical therapies Under the current Health Act (1958) the following practices do not require registration with local government. The information provided relates to general hygiene in minimising the risk and the spread of potentially harmful microorganisms that may lead to infection. Adoption of the outlined information is encouraged. 5.1 Massage In performing various massage therapies, the operator needs to assess all possible infection risks and to consult their professional organisation. See the following sections for appropriate procedures to reduce the potential for the transmission of infection: • hands—see part A, section 3.3 • surfaces—see part A, section 4.2.2 • linen—see part A, section 2.3.5 • oils/creams—see part A, section 2.5. 5.2 Solaria Guidelines for the installation, maintenance and operation of solaria are outlined in AS/NZS 2635:2002 Solaria for cosmetic purposes. The standard seeks to increase the levels of safety associated with the use of solaria. The Department of Human Services recommends compliance. The following are key requirements of the standard. 5.2.1 Age limit It is recommended that an operator does not allow an individual under the age of 18 years to use a sun-tanning unit without parental or guardian consent. Any individual under the age of 15 years is strictly not permitted. 5.2.2 Warning notices Commercial premises should place one or more notices (of A4-size paper) presenting the following information (in legible print) within the immediate view of every client entering the premises and in each sun-tanning unit cubicle.