Three Components of Xenakis' Universe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

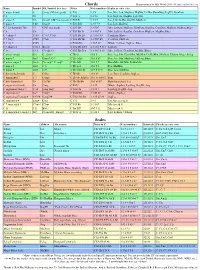

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Littérature Et Vocalité Chez Xenakis Ou Comment Traiter Des Abîmes Nicolas Darbon

Document generated on 09/24/2021 11 a.m. Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique Littérature et vocalité chez Xenakis ou comment traiter des abîmes Nicolas Darbon Volume 34, Number 1-2, 2014 Article abstract The mytheme of Chaos is studied through the vocal works of Xenakis. It is URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1030872ar representative of the history, the concerns, and the sensibility of the DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1030872ar “contemporary” (of the end of the twentieth century): although inspired by Greek antiquity, the treatment of the text oscillates between the poles of pure See table of contents abstraction and significant expression. Furious, stormy, the Xenakian Chaos can result from trauma, madness, and war, to indicate the state of what has no shape, the abyss, the deluge, the genesis, the perdition, to be a transition, Publisher(s) process, to represent the origin or the end of the world. So the composer wanted “to handle abysses” by the soloist or the choir vocality, to find “all the Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités cosmic wealth, but chaotically.” This article opens a diptych; the second section canadiennes is entitled “The Big Neolithic Mother in Serment-Orkos” (published by the Iannis Xenakis Center, University of Rouen). The postulate is that chaos theory ISSN and complexity theory belong themselves to an anthropology of the imagination. This article joins research on the transdiction (notion explained 1911-0146 (print) on the site of the CEREdI, University of Rouen): sound and body in the 1918-512X (digital) musico-literary transfers. -

3 Manual Microtonal Organ Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013

3 Manual Microtonal Organ http://www.bek.no/~ruben/Research/Downloads/software.html Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013 An interface to existing software A motivation for creating this instrument has been an interest for gaining experience with a large range of intonation systems. This software instrument is built with Max 61, as an interface to the Fluidsynth object2. Fluidsynth offers possibilities for retuning soundfont banks (Sf2 format) to 12-tone or full-register tunings. Max 6 introduced the dictionary format, which has been useful for creating a tuning database in text format, as well as storing presets. This tuning database can naturally be expanded by users, if tunings are written in the syntax read by this instrument. The freely available Jeux organ soundfont3 has been used as a default soundfont, while any instrument in the sf2 format can be loaded. The organ interface The organ window 3 MIDI Keyboards This instrument contains 3 separate fluidsynth modules, named Manual 1-3. 3 keysliders can be played staccato by the mouse for testing, while the most musically sufficient option is performing from connected MIDI keyboards. Available inputs will be automatically recognized and can be selected from the menus. To keep some of the manuals silent, select the bottom alternative "to 2ManualMicroORGANircamSpat 1", which will not receive MIDI signal, unless another program (for instance Sibelius) is sending them. A separate menu can be used to select a foot trigger. The red toggle must be pressed for this to be active. This has been tested with Behringer FCB1010 triggers. Other devices could possibly require adjustments to the patch. -

00 Title Page

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture SPATIALIZATION IN SELECTED WORKS OF IANNIS XENAKIS A Thesis in Music Theory by Elliot Kermit-Canfield © 2013 Elliot Kermit-Canfield Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2013 The thesis of Elliot Kermit-Canfield was reviewed and approved* by the following: Vincent P. Benitez Associate Professor of Music Thesis Advisor Eric J. McKee Associate Professor of Music Marica S. Tacconi Professor of Musicology Assistant Director for Graduate Studies *Signatures are on file in the School of Music ii Abstract The intersection between music and architecture in the work of Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001) is practically inseparable due to his training as an architect, engineer, and composer. His music is unique and exciting because of the use of mathematics and logic in his compositional approach. In the 1960s, Xenakis began composing music that included spatial aspects—music in which movement is an integral part of the work. In this thesis, three of these early works, Eonta (1963–64), Terretektorh (1965–66), and Persephassa (1969), are considered for their spatial characteristics. Spatial sound refers to how we localize sound sources and perceive their movement in space. There are many factors that influence this perception, including dynamics, density, and timbre. Xenakis manipulates these musical parameters in order to write music that seems to move. In his compositions, there are two types of movement, physical and apparent. In Eonta, the brass players actually walk around on stage and modify the position of their instruments to create spatial effects. -

S P O È Me E Lectronique

Densil Cabrera S o u n d S p a c e a n d E d g a r d V a r è s e ’ s P o è m e E l e c t r o n i q u e Master of Arts 1994 University of Technology, Sydney C E R T I F I C A T E I certify that this thesis has not already been submitted for any degree and is not being submitted as part of candidature for any other degree. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me and that any help that I have received in preparing this thesis, and all sources used, have been acknowledged in this thesis. Signature of Candidate i A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s The author acknowledges the specific assistance of the following people in the preparation of this thesis: Martin Harrison for supervision; Greg Schiemer for support in the early stages of research; Elizabeth Francis and Peter Keller for allowing the use of facilities at the University of New South Wales’ Infant Research Centre for the production of the Appendix; Joe Wolfe and Emery Schubert; Roberta Lukes for her correspondence; Kirsten Harley and Greg Walkerden for proof reading. The author also acknowledges an award from the University of Technology, Sydney Vice- Chancellor’s Postgraduate Student Conference Fund in 1992. ii T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s I n t r o d u c t i o n The Philips Pavilion and Poème Electronique Approaches C h a p t e r 1 - S o u n d i n t h e W a l l s Architecture, Music: A Lineage Music-Architecture: Hyperbolic Paraboloids Crystal Sculpture Domestic Images of Sound in Space Sound, Space, Surface C h a p t e r 2 - H y p e r b o l i c P a r a b o l o i d s A -

XENAKIS AS a SOUND SCULPTOR Makis Solomos

XENAKIS AS A SOUND SCULPTOR Makis Solomos To cite this version: Makis Solomos. XENAKIS AS A SOUND SCULPTOR. in welt@musik - Musik interkulturell, publi- cations de l’Institut für Neue Musik und Musikerziehung Darmstadt, volume 44, Mainz, Schott, 2004„ p. 161-169, 2004. hal-01202904 HAL Id: hal-01202904 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01202904 Submitted on 21 Sep 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 XENAKIS AS A SOUND SCULPTOR* Makis Solomos Abstract One of the main revolutions —and maybe the most important one— of twentieth century music is the emergence of sound. From Debussy to recent contemporary music, from rock’n’roll to electronica, the history of music has progressively and to some extent focused on the very foundation of music: sound. During this history —when, in some way, composition of sound takes the place of composition with sounds—, Xenakis plays a major role. Already from the 1950s, with orchestral pieces like Metastaseis (1953-54) or Pithoprakta (1955-56) and with electronic pieces like Diamorphoses (1957) or Concret PH (1958), he develops the idea of composition as composition-of-sound to such an extent that, if the expression was not already used for designating a new interdisciplinary artistic activity, we could characterize him as a “sound sculptor”. -

Diatope and La L ´Egende D'eer

Elisavet Kiourtsoglou An Architect Draws Sound 13 rue Clavel, 75019, Paris, France [email protected] and Light: New Perspectives on Iannis Xenakis’s Diatope and La Legende´ d’Eer (1978) Abstract: This article examines the creative process of Diatope, a multimedia project created by Iannis Xenakis in 1978 for the inauguration of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, utilizing analytical research of sources found in several archives. By interpreting Xenakis’s sketches and plans, the article elucidates for the first time the spatialization of La Legende´ d’Eer, the music featured in the Diatope. The findings of the research underline the importance of graphic and geometric representation for understanding Xenakis’s thinking, and they highlight the continuity and evolution of his theory and practice over time. Furthermore, the research findings present the means by which this key work of electroacoustic music might be spatialized today, now that the original space of the Diatope no longer exists. Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001) was trained as a civil distinct levels of Diatope—architecture, music, and engineer at the Polytechnic University of Athens light—were neither interdependent elements of the (NTUA) and became an architect during his collab- work nor merely disparate artistic projects merged oration with Le Corbusier (1947–1959). Later on, together. Xenakis presented a four-dimensional Xenakis devoted himself mainly to the composition spectacle based upon analogies between diverse of music, with the exception of purely architectural aspects of space–time reality. To achieve this he projects sporadically conceived for his friends and used elementary geometry (points and lines) as a for other composers. -

Helmholtz's Dissonance Curve

Tuning and Timbre: A Perceptual Synthesis Bill Sethares IDEA: Exploit psychoacoustic studies on the perception of consonance and dissonance. The talk begins by showing how to build a device that can measure the “sensory” consonance and/or dissonance of a sound in its musical context. Such a “dissonance meter” has implications in music theory, in synthesizer design, in the con- struction of musical scales and tunings, and in the design of musical instruments. ...the legacy of Helmholtz continues... 1 Some Observations. Why do we tune our instruments the way we do? Some tunings are easier to play in than others. Some timbres work well in certain scales, but not in others. What makes a sound easy in 19-tet but hard in 10-tet? “The timbre of an instrument strongly affects what tuning and scale sound best on that instrument.” – W. Carlos 2 What are Tuning and Timbre? 196 384 589 amplitude 787 magnitude sample: 0 10000 20000 30000 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 time: 0 0.23 0.45 0.68 frequency in Hz Tuning = pitch of the fundamental (in this case 196 Hz) Timbre involves (a) pattern of overtones (Helmholtz) (b) temporal features 3 Some intervals “harmonious” and others “discordant.” Why? X X X X 1.06:1 2:1 X X X X 1.89:1 3:2 X X X X 1.414:1 4:3 4 Theory #1:(Pythagoras ) Humans naturally like the sound of intervals de- fined by small integer ratios. small ratios imply short period of repetition short = simple = sweet Theory #2:(Helmholtz ) Partials of a sound that are close in frequency cause beats that are perceived as “roughness” or dissonance. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Vagopoulou, Evaggelia Title: Cultural tradition and contemporary thought in Iannis Xenakis's vocal works General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Cultural Tradition and Contemporary Thought in lannis Xenakis's Vocal Works Volume I: Thesis Text Evaggelia Vagopoulou A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordancewith the degree requirements of the of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, Music Department. -

Exploring Xenakis Performance, Practice, Philosophy

Exploring Xenakis Performance, Practice, Philosophy Edited by Alfia Nakipbekova University of Leeds, UK Series in Music Copyright © 2019 Vernon Press, an imprint of Vernon Art and Science Inc, on behalf of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Music Library of Congress Control Number: 2019931087 ISBN: 978-1-62273-323-1 Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: Photo of Iannis Xenakis courtesy of Mâkhi Xenakis. Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Table of contents Introduction v Alfia Nakipbekova Part I - Xenakis and the avant-garde 1 Chapter 1 ‘Xenakis, not Gounod’: Xenakis, the avant garde, and May ’68 3 Alannah Marie Halay and Michael D. -

Visualizing Acoustic Space Visualiser L'espace Acoustique Gascia Ouzounian

Document generated on 09/26/2021 3:22 a.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines Visualizing Acoustic Space Visualiser l'espace acoustique Gascia Ouzounian Musique in situ Article abstract Volume 17, Number 3, 2007 This article explores concepts of acoustic space in postwar media studies, architecture, and spatial music composition. A common link between these URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/017589ar areas was the characterization of acoustic space as indeterminate, chaotic, and DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/017589ar sensual, a category defined in opposition to a definite, ordered, and rationalized visual space. These conceptual polarities were vividly evoked in See table of contents an iconic sound-and-light installation, the Philips Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World Fair. Designed by Le Corbusier, the Philips Pavilion also featured a black-and-white film, color projections, hanging sculptures, and Edgard Varèse’s Poème électronique, a spatial composition distributed over hundreds Publisher(s) of loudspeakers and multiple sound routes. Typically remembered as a Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal sequence of abstract sound geometries, the author argues that Poème électronique was instead an allegorical work that told a “story of all humankind.” This narrative was expressed through a series of conceptual ISSN binaries that juxtaposed such categories as primitive/enlightened, female/male, 1183-1693 (print) racialized/white, and sensual/ rational– contrasts that were framed within the 1488-9692 (digital) larger dialectic between acoustic and visual space. Explore this journal Cite this article Ouzounian, G. (2007). Visualizing Acoustic Space. Circuit, 17(3), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.7202/017589ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2007 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Iannis Xenakis, Roberta Brown, John Rahn Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol

Xenakis on Xenakis Author(s): Iannis Xenakis, Roberta Brown, John Rahn Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 25, No. 1/2, 25th Anniversary Issue (Winter - Summer, 1987), pp. 16-63 Published by: Perspectives of New Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/833091 Accessed: 29/04/2009 05:06 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=pnm. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Perspectives of New Music is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Perspectives of New Music. http://www.jstor.org XENAKIS ON XENAKIS 47W/ IANNIS XENAKIS INTRODUCTION ITSTBECAUSE he wasborn in Greece?That he wentthrough the doorsof the Poly- technicUniversity before those of the Conservatory?That he thoughtas an architect beforehe heardas a musician?Iannis Xenakis occupies an extraodinaryplace in the musicof our time.