Egyptian Romany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Folk Religion and Migración: La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 5-2020 A Case Study of Folk Religion and Migración: La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde Zulema Denise Santana California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Recommended Citation Santana, Zulema Denise, "A Case Study of Folk Religion and Migración: La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde" (2020). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 871. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/871 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Case Study of Folk Religion and Migración: La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde Global Studies Capstone Project Report Zulema D. Santana May 8th, 2020 California State University Monterey Bay 1 Introduction Religion has helped many immigrants establish themselves in their new surroundings in the United States (U.S.) and on their journey north from Mexico across the US-Mexican border (Vásquez and Knott 2014). They look to their God and then to their Mexican Folk Saints, such as La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde, for protection and strength. This case study focuses on how religion— in particular Folk Saints such as La Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde— can give solace and hope to Mexican migrants, mostly Catholics, when they cross the border into the U.S, and also after they settle in the U.S. -

Download Download

Nisan / The Levantine Review Volume 4 Number 2 (Winter 2015) Identity and Peoples in History Speculating on Ancient Mediterranean Mysteries Mordechai Nisan* We are familiar with a philo-Semitic disposition characterizing a number of communities, including Phoenicians/Lebanese, Kabyles/Berbers, and Ismailis/Druze, raising the question of a historical foundation binding them all together. The ethnic threads began in the Galilee and Mount Lebanon and later conceivably wound themselves back there in the persona of Al-Muwahiddun [Unitarian] Druze. While DNA testing is a fascinating methodology to verify the similarity or identity of a shared gene pool among ostensibly disparate peoples, we will primarily pursue our inquiry using conventional historical materials, without however—at the end—avoiding the clues offered by modern science. Our thesis seeks to substantiate an intuition, a reading of the contours of tales emanating from the eastern Mediterranean basin, the Levantine area, to Africa and Egypt, and returning to Israel and Lebanon. The story unfolds with ancient biblical tribes of Israel in the north of their country mixing with, or becoming Lebanese Phoenicians, travelling to North Africa—Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya in particular— assimilating among Kabyle Berbers, later fusing with Shi’a Ismailis in the Maghreb, who would then migrate to Egypt, and during the Fatimid period evolve as the Druze. The latter would later flee Egypt and return to Lebanon—the place where their (biological) ancestors had once dwelt. The original core group was composed of Hebrews/Jews, toward whom various communities evince affinity and identity today with the Jewish people and the state of Israel. -

Death and Divine Judgement in Ecclesiastes

Durham E-Theses DEATH AND DIVINE JUDGEMENT IN ECCLESIASTES TAKEUCHI, KUMIKO How to cite: TAKEUCHI, KUMIKO (2016) DEATH AND DIVINE JUDGEMENT IN ECCLESIASTES, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11382/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Kumiko Takeuchi DEATH AND DIVINE JUDGEMENT IN ECCLESIASTES Abstract The current scholarly consensus places Ecclesiastes’ composition in the postexilic era, sometime between the late Persian and early Hellenistic periods, leaning towards the late fourth or early third centuries BCE. Premised on this consensus, this thesis proposes that the book of Ecclesiastes is making a case for posthumous divine judgement in order to rectify pre-mortem injustices. Specifically, this thesis contends that issues relating to death and injustice raised by Qohelet in the book of Ecclesiastes point to the necessity of post-mortem divine judgement. -

Christ in Yaqui Garb: Teresa Urrea's Christian Theology and Ethic

religions Article Christ in Yaqui Garb: Teresa Urrea’s Christian Theology and Ethic Ryan Ramsey Religion Department, Baylor University, Waco, TX 76706, USA; [email protected] Abstract: A healer, Mexican folk saint, and revolutionary figurehead, Teresa Urrea exhibited a deeply inculturated Christianity. Yet in academic secondary literature and historical fiction that has arisen around Urrea, she is rarely examined as a Christian exemplar. Seen variously as an exemplary feminist, chicana, Yaqui, curandera, and even religious seeker, Urrea’s self-identification with Christ is seldom foregrounded. Yet in a 1900 interview, Urrea makes that relation to Christ explicit. Indeed, in her healing work, she envisioned herself emulating Christ. She understood her abilities to be given by God. She even followed an ethic which she understood to be an emulation of Christ. Closely examining that interview, this essay argues that Urrea’s explicit theology and ethic is, indeed, a deeply indigenized Christianity. It is a Christianity that has attended closely to the religion’s central figure and sought to emulate him. Yet it is also a theology and ethic that emerged from her own social and geographic location and, in particular, the Yaqui social imaginary. Urrea’s theology and ethics—centered on the person of Christ—destabilized the colonial order and forced those who saw her to see Christ in Yaqui, female garb. Keywords: transregional theologies; World Christianity; Christian theology; curanderismo; mysticism; borderlands religion; comparative and transregional history and mission; Porfiriato; decolonial theory Citation: Ramsey, Ryan. 2021. Christ in Yaqui Garb: Teresa Urrea’s Christian Theology and Ethic. 1. Introduction Religions 12: 126. -

Veleia 27.Indd

EL SISTEMA DUAL DE L’ESCRIPTURA IBÈRICA SUD-ORIENTAL Resum: Aquest article planteja l’existència d’un sistema dual en el signari ibèric sud-ori- ental similar al ja conegut en el signari ibèric nord-oriental, però més extens, atès que a més d’afectar als signes sil·làbics oclusius dentals i velars, també afecta almenys una de les sibilants, una de les vibrants i a la nasal. Pel que fa a l’origen de les escriptures paleohispàniques, aquesta troballa qüestiona la hipòtesi tradicional que defensa la derivació directa entre els dos signaris ibèrics i permet plantejar que el dualisme estigués almenys ja present en el primer antecessor comú d’aquests dos signaris. Paraules clau: Llengua ibèrica, escriptura ibèrica, sistema dual, escriptures paleohispà- niques. Abstract: This article discusses the existence of a dual system in the southeastern Iberian script similar to that already known in the northeastern Iberian script, but more extensive, as well as affecting the occlusive dentals and velars syllabic signs, it also affects at least one of the sibilants, one of the trills and the nasal signs. As regards the origin of the Paleohispanic scripts, this finding challenges the traditional assumption that advocates direct derivation between the two Iberian scripts and allows us to suggest that dualism was already present in at least the first common ancestor of these two scripts. Key words: Iberian language, Iberian script, Iberian inscription, Paleohispanic scripts. Resumen: Este artículo plantea la existencia de un sistema dual en el signario ibérico su- roriental similar al ya conocido en el signario ibérico nororiental, pero más extenso, pues- to que además de afectar a los signos silábicos oclusivos dentales y velares, también afecta al menos a una de las sibilantes, una de les vibrantes y a la nasal. -

Timeline / 1810 to 1930

Timeline / 1810 to 1930 Date Country Theme 1810 - 1880 Tunisia Fine And Applied Arts Buildings present innovation in their architecture, decoration and positioning. Palaces, patrician houses and mosques incorporate elements of Baroque style; new European techniques and decorative touches that recall Italian arts are evident at the same time as the increased use of foreign labour. 1810 - 1880 Tunisia Fine And Applied Arts A new lifestyle develops in the luxurious mansions inside the medina and also in the large properties of the surrounding area. Mirrors and consoles, chandeliers from Venice etc., are set alongside Spanish-North African furniture. All manner of interior items, as well as women’s clothing and jewellery, experience the same mutations. 1810 - 1830 Tunisia Economy And Trade Situated at the confluence of the seas of the Mediterranean, Tunis is seen as a great commercial city that many of her neighbours fear. Food and luxury goods are in abundance and considerable fortunes are created through international trade and the trade-race at sea. 1810 - 1845 Tunisia Migrations Taking advantage of treaties known as Capitulations an increasing number of Europeans arrive to seek their fortune in the commerce and industry of the regency, in particular the Leghorn Jews, Italians and Maltese. 1810 - 1850 Tunisia Migrations Important increase in the arrival of black slaves. The slave market is supplied by seasonal caravans and the Fezzan from Ghadames and the sub-Saharan region in general. 1810 - 1930 Tunisia Migrations The end of the race in the Mediterranean. For over 200 years the Regency of Tunis saw many free or enslaved Christians arrive from all over the Mediterranean Basin. -

THE PUNIC WARS: a “CLASH of CIVILIZATIONS” in ANTIQUITY Mădălina STRECHIE

International Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol. XXI No 2 2015 THE PUNIC WARS: A “CLASH OF CIVILIZATIONS” IN ANTIQUITY Mădălina STRECHIE University of Craiova, Romania [email protected] Abstract: The conflict that opposed the Carthaginians, called puny by the Romans, and the Eternal City, was one of epic proportions, similar to the Iliad, because, just as in the Iliad one of the combatants was removed forever, not only from the political game of the region, but also from history. The Punic Wars lasted long, the reason/stake was actually the control of the Mediterranean Sea, one of the most important spheres of influence in Antiquity. These military clashes followed the patterns of a genuine “clash of civilizations”, there was a confrontation of two civilizations with their military blocks, interests, mentalities, technologies, logistics, strategies and manner of belligerence. The two civilizations, one of money, the other of pragmatism, opposed once again, after the Iliad and the Greco-Persian wars, the Orient (and North Africa) with the West, thus redrawing the map of the world power. The winner in this “clash” was Rome, by the perseverance, tenacity and national unity of its army to the detriment of Carthage, a civilization of money, equally pragmatic, but lacking national political unity. So the West was victorious, changing the Roman winners in the super-power of the ancient world, a sort of gendarme of the world around the Mediterranean Sea which was turned into a Roman lake (Mare Nostrum.) Keywords: Mediterranean Sea, “clash of civilizations”, wars, Rome, Carthage. 1. Introduction genuine “clash of civilizations”[1], the The Punic wars represented a new “clash of winner eliminated the defeated one and civilizations” in Antiquity after the Trojan took over its empire. -

1 Introduction and the Kidnapping of Women

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-68943-4 - Herodotus and the Persian Wars John Claughton Excerpt More information Introduction and the 1 kidnapping of women IA H T Y C Aral S Sea COLCHIS Black Sea Caspian SOGDIA Sea THRACE IA RYG ARMENIA R PH LESSE CAPPADOCIA MARGIANA GREATER LYDIA PHRYGIA Athens Argos Sardis I O P AMP LIA N CARIA LYCIA HY Sparta IA CILICIA ASSYRIA HYRCANIA BACTRIA Cyprus MEDIA Ecbatana PARTHIA PHOENICIA Sidon BABYLONIA DRANGIANA Mediterranean Sea Tyre ABARNAHARA Susa ELAM Babylon ARIA Pasargadae Memphis Persepolis N PERSIA ARACHOSIA P e r CARMANIA EGYPT si an Gu GEDROSIA Red Sea lf 0 400 km 0 400 miles The Persian empire and neighbouring territories in the fi fth century BC. Although Herodotus’ work culminates in the great battles of 490 BC and 480–479 BC, his work is remarkable in its range. He begins with the world of myth and travels through many places and over generations in time to explore the relations between the Greeks and the Persians. Introduction and the kidnapping of women 1 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-68943-4 - Herodotus and the Persian Wars John Claughton Excerpt More information Introduction This is the presentation of the enquiry of Herodotus of Halicarnassus. The purpose of this work is to ensure that the actions of mankind are not rubbed out by time, and that great and wondrous deeds, some performed by the Greeks, some by non-Greeks, are not without due glory. In particular, the purpose is to explain why they waged war against each other. -

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ROOTS of CHRISTIANITY, 2ND EDITION Vii

The Ancient Egyptian Roots of Christianity Expanded Second Edition Moustafa Gadalla Maa Kheru (True of Voice) Tehuti Research Foundation International Head Office: Greensboro, NC, U.S.A. The Ancient Egyptian Roots of Christianity Expanded Second Edition by MOUSTAFA GADALLA Published by: Tehuti Research Foundation (formerly Bastet Publishing) P.O. Box 39491 Greensboro, NC 27438 , U.S.A. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recorded or by any information storage and retrieVal system with-out written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. This second edition is a reVised and enhanced edition of the same title that was published in 2007. Copyright 2007 and 2016 by Moustafa Gadalla, All rights reserved. Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gadalla, Moustafa, 1944- The Ancient Egyptian Roots of Christianity / Moustafa Gadalla. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. Library of Congress Control Number: 2016900013 ISBN-13(pdf): 978-1-931446-75-4 ISBN-13(e-book): 978-1-931446-76-1 ISBN-13(pbk): 978-1-931446-77-8 1. Christianity—Origin. 2. Egypt in the Bible. 3. Egypt—Religion. 4. Jesus Christ—Historicity. 5. Tutankhamen, King of Egypt. 6. Egypt—History—To 640 A.D. 7. Pharaohs. I. Title. BL2443.G35 2016 299.31–dc22 Updated 2016 CONTENTS About the Author vii Preface ix Standards and Terminology xi Map of Ancient Egypt xiii PART I : THE ANCESTORS OF THE CHRIST KING Chapter 1 -

Degree Rite of Memphis for the Instructi

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY THIS BOOK IS ONE OF A COLLECTION MADE BY BENNO LOEWY 1854-1919 AND BEQUEATHED TO CORNELL UNIVERSITY Cornell University Library HS825 .B97 3 1924 030 318 806 olln,anx Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030318806 EGYPTIAN MASONIC HISTORY OF THE ORIGINAL AND UNABRIDGED ANCIENT AND NINETY-SIX (96°) DEGHEE RITE OF MEMPHIS. FOR THE INSTRUCTION AND GOVERNMENT OF ~ THE CRAFT. Fnblislied, edited, translated, and compiled by Cai,tin C. Burt, 9I>° A. U. P. 0. E. T., 32° m tlie A. and A. Bite, and Grand MastSr General Ad Yitem of the E.'. M.'. B.'. of M.., Egyptian year or true light, 000,000,000, Tork Masonic date, A. L. S879, and Era Vulgate 1R79. UTIOA, N. T. WHITE & FLOYD, PEINTBES, COB. BEOAD AND JOHN STKKETS. 5879. Entered according to Actt of CongreeB,Congreea, in tnethe yearye»rl879,1 by OALTnf C. BuBt, n the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at WasMngton, and this Copy- right claims and covers the Title and the following, viz: The Masonic History of the Original and Unabridged Ancient Ninety-Six Degree, (96°) Kite of Memphis; for the instruction and governmenl of the craft for the entire civilized Cosmos, wherever the refulgent and beneficent rays of Masonic intelligence and benevolence is dispersed and the mystic art is tolerated Together with a history of tliis Ancient Order from its origin, through the dark ages of the world, to its recognition in Fiance and promulgation in Europe, and its final translation, establishment and enuncia- tion in America, history of the formation of bodies, and record of the present Grand Body (or Sovereign Sanctuary) in 1867, with copies of charters and other correspondence of this Ancient and Primitive Eite, viz: the Egyptian ilfa«onic Kite of Memphis: together with its Masonic Calendar and translation of the non-esoteric work. -

The Ancient Egyptian Universal Writing Modes by Moustafa Gadalla

The Ancient Egyptian Universal Writing Modes Moustafa Gadalla Maa Kheru (True of Voice) Tehuti Research Foundation International Head Office: Greensboro, NC, U.S.A. The Ancient Egyptian Universal Writing Modes by Moustafa Gadalla Published by: Tehuti Research Foundation P.O. Box 39491 Greensboro, NC 27438, U.S.A. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recorded or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Copyright © 2017 by Moustafa Gadalla, All rights reserved. Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gadalla, Moustafa, 1944- The Ancient Egyptian Universal Writing Modes / Moustafa Gadalla. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references Library of Congress Control Number: 2016900021 ISBN-13(pdf): 978-1-931446-91-4 ISBN-13(e-book): 978-1-931446- 92-1 ISBN-13(pbk.): 978-1-931446-93-8 1. Egypt—Civilization—To 332 B.C. 2. Civilization, Western—Egyptian influences. 3. Egyptian language—Influence on European languages. 4. Egypt—Antiquities. 5. Egypt—History—To 640 A.D. I. Title. CONTENTS About the Author xiii Preface xv Standards and Terminology xxi The 28 ABGD Letters & Pronunciations xxv Map of Egypt and Surrounding xxix Countries PART I : DENIAL, DISTORTION AND DIVERSION Chapter 1 : The Archetypal Primacy of 3 The Egyptian Alphabet 1.1 The Divine “Inventor” of The Egyptian 3 Alphabetical Letters 1.2 Remote Age of Egyptian -

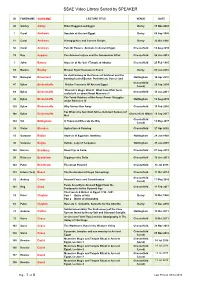

SSAE Video Library Sorted by SPEAKER

SSAE Video Library Sorted by SPEAKER ID FORENAME SURNAME LECTURE TITLE VENUE DATE 40 Shirley Addey Rider Haggard and Egypt Derby 15 Nov 2003 7 Carol Andrews Amulets of Ancient Egypt Derby 09 Sep 1995 11 Carol Andrews Hieroglyphics and Cursive Scripts Derby 12 Oct 1996 56 Carol Andrews Pets Or Powers: Animals In Ancient Egypt Chesterfield 14 Aug 2010 78 Ray Aspden The Armana Letters and the Dahamunzu Affair Chesterfield 06 Jun 2012 3 John Baines Aspects of the Seti I Temple at Abydos Chesterfield 25 Feb 1995 53 Marsia Bealby Minoan Style Frescoes in Avaris Derby 05 Jun 2010 He shall belong to the flames of Sekhmet and the 153 Maragret Beaumont Nottingham 14 Apr 2018 burning heat of Bastet: Punishment, Curses and Threat Formulae in Ancient Egypt. Chesterfield 47 Dylan Bickerstaffe Hidden Treasures Of Ancient Egypt 28 Sep 2009 (Local) ‘Pharoah’s Magic Wand? What have DNA Tests 68 Dylan Bickerstaffe Chesterfield 13 Jun 2011 really told us about Royal Mummies?’ The Tomb-Robbers of No-Amun:Power Struggles 98 Dylan Bickerstaffe Nottingham 10 Aug 2013 under Rameses IX 129 Dylan Bickerstaffe Why Sinhue Ran Away Chesterfield 13 Feb 2016 For Whom the Sun Doth Shine, Nefertari Beloved of 148 Dylan Bickerstaffe Chesterfield (Main) 16 Sep 2017 Mut Chesterfield 143 Val Billingham A Thousand Miles Up the Nile 13 May 2017 (Local) 33 Victor Blunden Agriculture & Farming Chesterfield 27 Apr 2002 15 Suzanne Bojtos Aspects of Egyptian Jewellery Nottingham 24 Jan 1998 36 Suzanne Bojtos Hathor, Lady of Turquoise Nottingham 25 Jan 2003 100 Karren Bradbury Road