Hellenistic World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Kings Become Philosophers: the Late Republican Origins of Cicero’S Political Philosophy

When Kings Become Philosophers: The Late Republican Origins of Cicero’s Political Philosophy By Gregory Douglas Smay A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Erich S. Gruen, Chair Professor Carlos F. Noreña Professor Anthony A. Long Summer 2016 © Copyright by Gregory Douglas Smay 2016 All Rights Reserved Abstract When Kings Become Philosophers: The Late Republican Origins of Cicero’s Political Philosophy by Gregory Douglas Smay Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Erich S. Gruen, Chair This dissertation argues that Cicero’s de Republica is both a reflection of, and a commentary on, the era in which it was written to a degree not previously recognized in Ciceronian scholarship. Contra readings which treat the work primarily as a theoretical tract in the tradition of late Hellenistic philosophy, this study situates the work within its historical context in Late Republican Rome, and in particular within the personal experience of its author during this tumultuous period. This approach yields new insights into both the meaning and significance of the work and the outlook of the individual who is our single most important witness to the history of the last decades of the Roman Republic. Specifically, the dissertation argues that Cicero provides clues preserved in the extant portions of the de Republica, overlooked by modern students in the past bur clearly recognizable to readers in his own day, indicating that it was meant to be read as a work with important contemporary political resonances. -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Toronto! Welcome to the 118Th Joint Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and the Society for Classical Studies

TORONTO, ONTARIO JANUARY 5–8, 2017 Welcome to Toronto! Welcome to the 118th Joint Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and the Society for Classical Studies. This year we return to Toronto, one of North America’s most vibrant and cosmopolitan cities. Our sessions will take place at the Sheraton Centre Toronto Hotel in the heart of the city, near its famed museums and other cultural organizations. Close by, you will find numerous restaurants representing the diverse cuisines of the citizens of this great metropolis. We are delighted to take this opportunity of celebrating the cultural heritage of Canada. The academic program is rich in sessions that explore advances in archaeology in Europe, the Table of Contents Mediterranean, Western Asia, and beyond. Among the highlights are thematic sessions and workshops on archaeological method and theory, museology, and also professional career General Information .........3 challenges. I thank Ellen Perry, Chair, and all the members of the Program for the Annual Meeting Program-at-a-Glance .....4-7 Committee for putting together such an excellent program. I also want to commend and thank our friends in Toronto who have worked so hard to make this meeting a success, including Vice Present Exhibitors .......................8-9 Margaret Morden, Professor Michael Chazan, Professor Catherine Sutton, and Ms. Adele Keyes. Thursday, January 5 The Opening Night Public Lecture will be delivered by Dr. James P. Delgado, one of the world’s Day-at-a-Glance ..........10 most distinguished maritime archaeologists. Among other important responsibilities, Dr. Delgado was Executive Director of the Vancouver Maritime Museum, Canada, for 15 years. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2013 Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Custom Citation Kinney, Dale. "Spoliation in Medieval Rome." In Perspektiven der Spolienforschung: Spoliierung und Transposition. Ed. Stefan Altekamp, Carmen Marcks-Jacobs, and Peter Seiler. Boston: De Gruyter, 2013. 261-286. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/70 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Topoi Perspektiven der Spolienforschung 1 Berlin Studies of the Ancient World Spoliierung und Transposition Edited by Excellence Cluster Topoi Volume 15 Herausgegeben von Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler De Gruyter De Gruyter Dale Kinney Spoliation in Medieval Rome i% The study of spoliation, as opposed to spolia, is quite recent. Spoliation marks an endpoint, the termination of a buildlng's original form and purpose, whÿe archaeologists tradition- ally have been concerned with origins and with the reconstruction of ancient buildings in their pristine state. Afterlife was not of interest. Richard Krautheimer's pioneering chapters L.,,,, on the "inheritance" of ancient Rome in the middle ages are illustrated by nineteenth-cen- tury photographs, modem maps, and drawings from the late fifteenth through seventeenth centuries, all of which show spoliation as afalt accomplU Had he written the same work just a generation later, he might have included the brilliant graphics of Studio Inklink, which visualize spoliation not as a past event of indeterminate duration, but as a process with its own history and clearly delineated stages (Fig. -

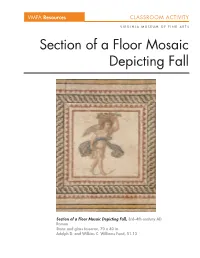

Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall

VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall, 3rd–4th century AD Roman Stone and glass tesserae, 70 x 40 in. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 51.13 VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Object Information Romans often decorated their public buildings, villas, and houses with mosaics—pictures or patterns made from small pieces of stone and glass called tesserae (tes’-er-ray). To make these mosaics, artists first created a foundation (slightly below ground level) with rocks and mortar and then poured wet cement over this mixture. Next they placed the tesserae on the cement to create a design or a picture, using different colors, materials, and sizes to achieve the effects of a painting and a more naturalistic image. Here, for instance, glass tesserae were used to add highlights and emphasize the piled-up bounty of the harvest in the basket. This mosaic panel is part of a larger continuous composition illustrating the four seasons. The seasons are personified aserotes (er-o’-tees), small boys with wings who were the mischievous companions of Eros. (Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, the Greek god and goddess of love, were known in Rome as Cupid and Venus.) Erotes were often shown in a variety of costumes; the one in this panel represents the fall season and wears a tunic with a mantle around his waist. He carries a basket of fruit on his shoulders and a pruning knife in his left hand to harvest fall fruits such as apples and grapes. -

Architectural Spolia and Urban Transformation in Rome from the Fourth to the Thirteenth Century

Patrizio Pensabene Architectural Spolia and Urban Transformation in Rome from the Fourth to the Thirteenth Century Summary This paper is a historical outline of the practice of reuse in Rome between the th and th century AD. It comments on the relevance of the Arch of Constantine and the Basil- ica Lateranensis in creating a tradition of meanings and ways of the reuse. Moreover, the paper focuses on the government’s attitude towards the preservation of ancient edifices in the monumental center of Rome in the first half of the th century AD, although it has been established that the reuse of public edifices only became a normal practice starting in th century Rome. Between the th and th century the city was transformed into set- tlements connected to the principal groups of ruins. Then, with the Carolingian Age, the city achieved a new unity and several new, large-scale churches were created. These con- struction projects required systematic spoliation of existing marble. The city enlarged even more rapidly in the Romanesque period with the construction of a large basilica for which marble had to be sought in the periphery of the ancient city. At that time there existed a highly developed organization for spoliating and reworking ancient marble: the Cos- matesque Workshop. Keywords: Re-use; Rome; Arch of Constantine; Basilica Lateranensis; urban transforma- tion. Dieser Artikel bietet eine Übersicht über den Einsatz von Spolien in Rom zwischen dem . und dem . Jahrhundert n. Chr. Er zeigt auf, wie mit dem Konstantinsbogen und der Ba- silica Lateranensis eine Tradition von Bedeutungsbezügen und Strategien der Spolienver- wendung begründet wurde. -

The Platform of the Temple of Venus and Rome

Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Construction History, Cottbus, May 2009 The Platform of the Temple of Venus and Rome C. González-Longo Architect, Edinburgh, UK D. Theodossopoulos University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK ABSTRACT: The Temple of Venus and Rome at the Roman Forum was allegedly designed by the emperor Ha- drian himself and was inaugurated in 135 AD. Its construction upon the Velia hill and precedent structures re- quired an exceptional design and execution, including the provision of a massive 167x 100 m artificial plat- form. Distinct historical developments on the site like the Vestibule of Nero’s Golden House and the later construction of the medieval church and monastery of Santa Maria Nova as well as the Mussolinian operations of Sventramenti in the first half of the 20th century, have influenced the construction and altered the presenta- tion of the platform. This paper intends to discuss the strategy, design, construction and current condition of this example of a lesser-known field of Roman structural technology. Foundations and platforms of this kind can offer invaluable information on the function of a temple, its history and structural performance, but theirs study is often neglected. INTRODUCTION The exceptional complex that includes the Temple of Venus and Rome and the Monastery of Santa Francesca Romana has not been studied previously as a single site and the various stages and interventions in its history have always been viewed with partial reference to specific areas. The authors have tried in the recent years to link such stages to a more global architectural understanding and conservation approach to the entire site. -

THE REACH of the ROMAN EMPIRE in ROUGH CILICIA by HUGHW.ELTON

THE ECONOMIC FRINGE: THE REACH OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE IN ROUGH CILICIA By HUGHW.ELTON Many discussions of the Roman economy are rather vague about what they mean by 'Roman'. Phrases such as 'Roman Europe' or 'the Roman Empire' often blur two different concepts, that of the cultures of Iron Age Europe and the political institution of the Roman Empire. Cultures in Iron Age Europe varied widely. The Welsh uplands or the Atlas mountains, for example, had an aceramic culture with few public buildings, though were mIed directly by Rome for several centuries. Other regions, not under Roman control, like the regions across the middle Danube, showed higher concentrations of Mediterranean consumer goods and coins than some of these aceramic areas. 1 In Mesopotamia, many societies were urban and literate, not differing in this respect from those in Italy or Greece. Thus, determining what was imperial Roman territory by archaeological criteria alone is very difficult? But these archaeological criteria are important for two reasons. First, they allow us to analyse the cultural and economic changes that occurred in Iron Age Europe between 100 B.C. and A.D. 250. Second, they allow for the possibility of change within Europe that was not caused by the Roman state? Unlike cultures within Iron Age Europe, the Roman Empire was a political structure, imposed by force and dedicated to extracting benefits for the mling elite of the city of Rome.4 As the empire developed and matured, its form changed, but it was never about the mIed, only the rulers. If we accept that the Empire was a political, not an archaeological, structure, it follows that an examination of 'Impact of Empire: Transformation of Economic Life', has to mean an examination of the impact of the Roman imperial state. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

The Gods and Their Worship

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-53212-9 — Roman Religion Valerie M. Warrior Excerpt More Information CHAPTER 1 - TH E GODS AND TH EIR WORSHIP © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-53212-9 — Roman Religion Valerie M. Warrior Excerpt More Information We Romans are far superior in religio, by which I mean the worship of the gods (cultus deorum). (Cicero, On the Nature of the Gods 2.8) There is no place in our city that is not filled with a sense of religion (religiones) and the gods. There are as many days fixed for annual sacrifices as there are places in which they can be performed. (Livy 5.52) - uins of ancient temples, interspersed among the excavated remains of Rthe ancient city, still bear witness that Rome was indeed a city filled with gods and a sense of religion. Prominent among the remains in the Roman Forum are the temples of Castor, Saturn, Vesta, and the deified emperor Antoninus Pius and his wife Faustina. Overlooking the Roman Forum is the Capitoline Hill, the site of the temple of Jupiter the Best and Greatest. In the area of the Forum Holitorium near the river Tiber, the modern tourist can see ancient columns incorporated into a side wall of the church of San Nicola in Carcere. In the Campus Martius area, the emperor Hadrian’s reconstruction of the Pantheon stands in all its grandeur amid the hustle and bustle of contemporary Rome, still bearing the inscription commemorating its original builder, Marcus Agrippa, who was a close associate of the emperor Augustus. -

Chronological Table of Important Dates in Latin Literature and History to AD 200

Harrison / Companion to Latin Literature Final 1.10.2004 3:19am page ix Chronological Table of Important Dates in Latin Literature and History to AD 200 Full descriptions of the works of authors referred to here only by name are to be found in the ‘General Resources and Author Bibliographies’ section in the introduction (pp. 3–12). Dates given are usually consistent with the information in the Oxford Classical Dictionary (1996). ‘Caesar’ is the term used for the future Augustus between his adoption in Julius Caesar’s will (44) and his assumption of the name ‘Augustus’ in 27, rather than ‘Octavian’, a name he never used. Full accounts of the historical periods covered here are to be found in volumes 8–11 of the Cambridge Ancient History (1989–2000). The Early Republican period (beginnings to 90 BC) Key literary events Key historical events c. 240–after Livius Andronicus active 264–41 First Punic War (Rome wins) 207 BC as poet/dramatist 218–201 Second Punic War (Rome wins) c. 235–204 Naevius active as poet/ 200–146 Rome conquers Greece; Greek dramatist cultural influence on Rome c. 205–184 Plautus active as dramatist 149–146 Third and final Punic War (Rome conquers Carthage) 204–169 Ennius active as poet/dramatist ?200 Fabius Pictor’s first history 122–106 War against Jugurtha in North of Rome (in Greek) Africa (Rome wins) c. 190–149 Literary career of Cato 91–88 Social War in Italy (over issue 166–159 Plays of Terence produced of full Roman citizenship for 125–100 Lucilius active as satirist Latin communities) Harrison / Companion to Latin