Surveying the Administrative Boundaries of Lancashire And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notices and Proceedings for the North East of England 2454

Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Notices and Proceedings Publication Number: 2454 Publication Date: 18/12/2020 Objection Deadline Date: 08/01/2021 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 18/12/2020 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online PLEASE NOTE THE PUBLIC COUNTER IS CLOSED AND TELEPHONE CALLS WILL NO LONGER BE TAKEN AT HILLCREST HOUSE UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE The Office of the Traffic Commissioner is currently running an adapted service as all staff are currently working from home in line with Government guidance on Coronavirus (COVID-19). Most correspondence from the Office of the Traffic Commissioner will now be sent to you by email. There will be a reduction and possible delays on correspondence sent by post. The best way to reach us at the moment is digitally. Please upload documents through your VOL user account or email us. There may be delays if you send correspondence to us by post. At the moment we cannot be reached by phone. -

Health Profile Overview for Garforth and Swillington Ward

Garforth and Swillington Ward Health profile overview for Garforth and Swillington ward Population: 21,325 Garforth and Swillington ward has a GP registered Comparison of ward Leeds age structures July 2018. population of 21,325 making it the fifth smallest ward Mid range Most deprived 5th Least deprived 5th in Leeds with the majority of the ward population living in the second least deprived fifth of Leeds. In 100-104 Males: 10,389 Females: 10,936 Leeds terms the ward is ranked sixth least by 90-94 deprivation score . 80-84 70-74 The age profile of this ward is very different to Leeds, 60-64 but with many more elderly and far adults and children. 50-54 This profile presents a high level summary of health 40-44 related data sets for the Garforth and Swillington 30-34 ward. 20-24 10-14 All wards are ranked to display variation across Leeds 0-4 and this one is outlined in red. 6% 3% 0% 3% 6% Leeds overall is shown as a horizontal black line, Deprived Deprivation in this ward Leeds** (or the most deprived fifth**) is an orange dashed Proportions of this population within each deprivation 'quintile' horizontal. The MSOAs that make up this ward are overlaid or fifth of Leeds* (Leeds therefore has equal proportions of 20%) as red circles and often range widely. July 2018. 63% Most of the data is provided for the new wards as redesigned in 2018, however 'obese smokers', and 'child 37% obesity' are for the previous wards and the best match is used in these cases. -

Alwoodley Parish – Application For

ALWOODLEY PARISH COUNCIL APPLICATION FOR DESIGNATION OF A NEIGHBOURHOOD AREA Prepared on behalf of Alwoodley Parish Council 5 November 2013 Introduction Alwoodley, for the purposes of this application, is a civil parish created in 2008 within the City of Leeds. Some of the adjacent areas are commonly referred to as being in Alwoodley but do not form part of the civil parish. It lies some 5 miles north of the city centre on the northern edge of the West Yorkshire conurbation. The parish is on a ridge between the valleys of the River Aire and River Wharfe. It is bounded by the suburbs of Adel and Bramhope to the west, Harrogate Road to the east, Moor Allerton to the south and Harewood parish to the north. The northern part of the parish is mixed farmland in the Green Belt in which Eccup Reservoir is situated. To the north of the parish is the Harewood Estate. Moortown and Sandmoor golf courses lie within the parish together with part of Headingley golf course. There are several sports fields. The site of a Roman road crosses the parish from West to East, from Ilkley to Tadcaster, close to Alwoodley Lane. Alwoodley Old Hall stood adjacent to the site of Eccup Reservoir in the present grounds of Sandmoor Golf Club. Built in the 17th century it was demolished in 1969. Early on the 20th century Alwoodley became a leisure destination for Leeds inhabitants; before that it was an isolated agricultural community. Much of the suburban area was developed between 1920 and 1980 . Leeds Country Way and two long distance footpaths, the Dales Way and the Ebor Way, cross or lie on the edge of the parish. -

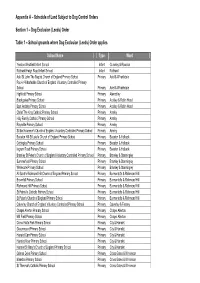

Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1

Appendix A – Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1 – Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order Table 1 – School grounds where Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order applies School Name Type Ward Yeadon Westfield Infant School Infant Guiseley & Rawdon Rothwell Haigh Road Infant School Infant Rothwell Adel St John The Baptist Church of England Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Pool-in-Wharfedale Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Highfield Primary School Primary Alwoodley Blackgates Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood East Ardsley Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood Christ The King Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Holy Family Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Raynville Primary School Primary Armley St Bartholomew's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Armley Beeston Hill St Luke's Church of England Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Cottingley Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Ingram Road Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Bramley St Peter's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Summerfield Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Whitecote Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley All Saint's Richmond Hill Church of England Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Brownhill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Richmond Hill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill St Patrick's Catholic Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill -

Leeds Bradford

Harrogate Road Yeadon Leeds West Yorkshire LS19 7XS INDUSTRIAL UNITS TO LET SAT NAV: LS19 7XS Unit 9 Unit 1B Knaresborough A59 Harrogate Produced by www.impressiondp.co.uk A1(M) Skipton Wetherby A65 A61 Keighley A660 A650 A658 LEEDS BRADFORD M621 M62 M62 M1 Old Bramhope Bramhope A658 Guiseley CONTACT Yeadon A65 Cookridge A660 0113 245 6000 Rawdon Rob Oliver Andrew Gent A658 [email protected] [email protected] A65 Iain McPhail Nick Prescott Horsforth Apperley [email protected] [email protected] Bridge A6120 Weetwood IMPORTANT NOTICE RELATING TO THE MISREPRESENTATION ACT 1967 AND THE PROPERTY MISDESCRIPTION ACT 1991. A65 GVA Grimley and Gent Visick on their behalf and for the sellers or lessors of this property whose agents they are, give notice that: (i) The Particulars are set out as a general outline only for the guidance of intending purchasers or lessees, and do not constitute, nor constitute part of, an offer or contract; (ii) All descriptions, dimensions, references to condition and necessary permissions for use and occupation, and other details are given in good faith and are believed to be correct, but any intending purchasers or tenants should not rely on them as statements or representations of fact, but must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise as to the correctness of each of them; (iii) No person employed by GVA Grimley and Gent Visick has any authority to make or give any representation or warranty in relation to this property. Unless otherwise stated prices and rents quoted are exclusive of VAT. -

LEEDS DIRECTORY, Hogg 1\[R John, 52 Camp Road Hollings John, Woollen Manufacturer and Hogg Thos

82 LEEDS DIRECTORY, Hogg 1\[r John, 52 Camp road Hollings John, woollen manufacturer and Hogg Thos. bookkeeper, 179 Dewsbury rd merchant, 10 York place; h Ilorsforth Hoggard Alfred, builder, 16 Booth street Hollings Thos. shopkeeper, Hunslet carr Hoggard & Co. machine mfTS. Robert street Hollings William, victualler, Old Nag's Hoggard George, tailor, 41 1\Iarshall street Head, 56 Kirkgate Hoggard John, beerhouse, 42 Marshall st Hollingworth Isaac, gutta percba manufac- Holden George, butcher, 48 Fleet street ; turer, Dewsbury road; h 5 Pemberton st h 1 Brunswick row Hollingworth Sarah, shopr. 18 St. 1\Iark s\ Holden Richard, shoemaker, 13 Elland row Hollingworth Thos. shopr. Granville ter Holder John, milk dealer, \Vright street Hollingworth Thos. painter, Lisbon street; Holder Thomas, undertaker, 31 Bank street h 7 Burley road Holford Mr George, Chapelt01cn Holl:lngworth Wm.travg.tea dlr.71 Ellerby lp. Holdforth Jas. & Son, silk spinners, Bank Hollins l\Iarmaduke, potato dealer, Vicax's Low Mills, Mill street, & Cookridge ~.fills croft; h Union street Holdforth Waiter (Jas. & Son); h .Arthington llollins Thomas, tripe dresser, Bunt street Holdsworth Mr Henry, 21 Grove terrace Holloway Richard, eating and beerhouse, Holdsworth James, glass and china dealer, 192 W ellipgton street 61 \Voodhousc lano Hollway Thomas Saunders, manager, lO Holdsworth James, beerhs. 26 Dewsbury rd Elmwood grove Holdsworth ~fr John, Eastfield, Chapeltou;n Holmes Abm. hairdresser, 20 Grey stree~ Holdsworth John, stone and marble mason, Holmes Ann, grocer, Butterley street 78 Castle street Holmes Chas. carver & gilder, 8 Albion st Holdsworth John, mason, Francis street Holmes Charles, shopkeeper, 7 Carlton st Holdsworth .T ohn, cashier, 49 Holdforth st Holmes David, auctioneer and furniture Holdsworth Jph. -

Health Profile Overview for Burmantofts and Richmond Hill Ward

Burmantofts and Richmond Hill Ward Health profile overview for Burmantofts and Richmond Hill ward Population: 30,290 Burmantofts and Richmond Hill ward has a GP Comparison of ward Leeds age structures July 2018. registered population of 30,290 making it the fifth Mid range Most deprived 5th Least deprived 5th largest ward in Leeds with the majority of the ward population living in the most deprived fifth of Leeds. 100-104 Males: 15,829 Females: 14,458 In Leeds terms the ward is ranked second by 90-94 deprivation score . 80-84 70-74 The age profile of this ward is similar to Leeds, but 60-64 with fewer elderly and many more children. 50-54 This profile presents a high level summary of health 40-44 related data sets for the Burmantofts and Richmond 30-34 Hill ward. 20-24 10-14 All wards are ranked to display variation across Leeds 0-4 and this one is outlined in red. 6% 3% 0% 3% 6% Leeds overall is shown as a horizontal black line, Deprived Deprivation in this ward Leeds** (or the most deprived fifth**) is an orange dashed Proportions of this population within each deprivation 'quintile' horizontal. The MSOAs that make up this ward are overlaid or fifth of Leeds* (Leeds therefore has equal proportions of 20%) as red circles and often range widely. July 2018. 81% Most of the data is provided for the new wards as redesigned in 2018, however 'obese smokers', and 'child obesity' are for the previous wards and the best match is 19% used in these cases. -

56 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

56 bus time schedule & line map 56 Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre View In Website Mode The 56 bus line (Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre: 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM (2) Moor Grange <-> Whinmoor: 5:15 AM - 10:40 PM (3) Swarcliffe <-> Moor Grange: 5:07 AM (4) Whinmoor <-> Leeds City Centre: 11:10 PM - 11:40 PM (5) Whinmoor <-> Moor Grange: 5:15 AM - 10:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 56 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 56 bus arriving. Direction: Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre 56 bus Time Schedule 26 stops Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Latchmere Drive, Moor Grange Latchmere Green, Leeds Tuesday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Latchmere Road, Moor Grange Wednesday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Old Farm Approach, Moor Grange Thursday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Friday 7:30 PM - 11:10 PM Old Oak Drive, West Park Old Oak Garth, Leeds Saturday 11:10 PM Beckett Park, West Park Ghyll Road, West Park 56 bus Info Woodbridge Crescent, Beckett Park Direction: Moor Grange <-> Leeds City Centre Stops: 26 Woodbridge Place, Beckett Park Trip Duration: 22 min Queenswood Drive, Leeds Line Summary: Latchmere Drive, Moor Grange, Latchmere Road, Moor Grange, Old Farm Approach, Queenswood Road, Beckett Park Moor Grange, Old Oak Drive, West Park, Beckett Jaques Close, Leeds Park, West Park, Ghyll Road, West Park, Woodbridge Crescent, Beckett Park, Woodbridge Place, Beckett Eden -

Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields in the Cookridge Area of Leeds, England

Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields in the Cookridge Area of Leeds, England S Y Ely, K Fuller, A D Gulson, P M Judd, A J Lowe and J Shaw Occupational Services Department, National Radiological Protection Board, Hospital Lane, Cookridge, Leeds, LS16 6RW, England. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The National Radiological Protection Board (NRPB) is an independent body that has responsibility for advising UK government departments and others on the protection of people from ionising and non-ionising radiation (NIR) hazards. NRPB undertakes research into NIR sources and effects, and provides a comprehensive measurement and advisory service. In addition, NRPB receives many thousands of enquiries each year from individuals who are concerned about their exposure to radio waves, particularly those emitted by mobile phone base stations at around 900 and 1800 MHz. This paper describes the response to one such enquiry from a Member of Parliament (MP) representing local community groups and residents, who were concerned about emissions from three large telecommunications installations close to their homes and local schools. A survey of the radio wave exposure in the area around the three installations was carried out, measuring the total exposures due to all radio signals from 30 MHz to 18 GHz, using a variety of antennas connected to a spectrum analyser. The measurement range was chosen to include all the emissions from the local transmitters, including mobile phone base stations, emergency services' radiocommunications, pagers and microwave dishes. Emissions from transmitters further away, such as broadcast television and radio signals, were also detected. The results are compared against the guidelines published by the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP). -

5Pm – 10Pm Friday 3Rd October

w w 5pm – 10pm Friday 3rd October Enjoy over 50 free arts events across the city centre #ArtintheDark @lightnightleeds lightnightleeds.co.uk Light Installations Music Storytelling Dance Street Theatre Film Performance Get Around UNIVERSITY BROTHERTON PARKINSON W LIBRARY BUILDING O Light Night: 1-53 50 O D H STANLEY 49 O There are lots of ways to enjoy the & AUDREY U S many events at Light Night. Create BURTON GALLERY E your own trail using this fold out L N map or join in with one of the MICHAEL D 52 R many guided walks or runs. SADLER H S BUILDING I 5 D W M N A I E L N V K CLOTHWORKERS A CENTENARY C HALL 53 51 3 STAGE @ LEEDS PORTLAND 45-46 W I L Y L O A QUEEN E W T BUILDING W E R D N R A N SQUARE A C E A L R L D 5 T T R 2 I W M O P A I P W L N COLLEGE Y Y O D O N W A K A C L A R E N OF ART O L 47 D C H FIRST DIRECT CIVIC O HALL U M ARENA S E 1 R E R T I L O S MERRION 6-8 N N CENTRE W Y CITY A Y E 1 MUSEUM E L 2 48 N W R A L MILLENNIUM O E E O V SQUARE D ST ANNES A L 4-5 D W A THE CATHEDRAL H M E R R I O N S T C CARRIAGEWORKS O E G R E A T G E O R G E S T 31 U ST JOHN’S T 27 S A L CHURCH E G T P NATION OF SHOPKEEPERS G S 32-34 I L 29 D RENEGADE R A E R B N 19-21 G 28 HOWARD O 22-25 E D DORTMUND W F 26 ASSEMBLY ROOMS I SQUARE E X 9-12 HENRY R N O THE ART GALLERY K 30 TOWN HALL CENTRAL MOORE LIGHT H E O T H E A D R O W A T E L S T G LIBRARY E A O A 15 NORTHERN 17-18 T THE CORE E VICTORIA GARDENS C N BALLET E N D T VICTORIA H E H E S WEST YORKSHIRE A E A D R O W S QUARTER T PLAYHOUSE R L O W E H E A D R A L P T H E B I L O N P L A C T E -

The State of Men's Health in Leeds

The State of Men’s Health in Leeds: Data Dr. Amanda Seims, Leeds Beckett University Professor Alan White, Leeds Beckett University 1 2 To reference this document: Seims A. and White A. (2016) The State of Men’s Health in Leeds: Data Report. Leeds: Leeds Beckett University and Leeds City Council. ISBN: 978-1-907240-64-5 This study was funded by Leeds City Council Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following individuals for their input and feedback and also for their commitment to men’s health in Leeds: Tim Taylor and Kathryn Jeffries Dr Ian Cameron DPH and Cllr Lisa Mulherin James Womack and Richard Dixon - Leeds Public Health intelligence team 1 Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction and data analyses .................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Analysis of routinely collected health, socio-economic and service use data ............................. 9 2 The demographic profile of men in Leeds ................................................................................. 10 2.1 The male population ................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Population change for Leeds ...................................................................................................... 11 2.3 Ethnic minority men in Leeds .................................................................................................... -

Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment

Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment 31st January 2011 PHARMACEUTICAL NEEDS ASSESSMENT Welcome . 1 1 What are pharmaceutical services? . 2 2 What is a pharmacy needs assessment? . 2 3 What is the pharmacy needs assessment for? . 3 4 Executive summary . 4 5 The Leeds population: General overview . 4 5 1. Age . 5 5 .2 Life expectancy . 5 5 .3 Ethnicity . 5 5 4. Deprivation . 5 6 Health profile of Leeds . 6 6 1. Causes of ill health . 6 6 1. 1. Alcohol . 6 6 1. .2 Drugs . 6 6 1. .3 Smoking . 7 6 1. 4. Sexual health . 7 6 1. 5. Obesity . 8 6 .2 Long term health conditions . 8 6 .2 1. Diabetes . 8 6 .2 .2 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease . 9 6 .2 .3 Coronary heart disease . 9 6 .2 4. Mental health . 9 6 .3 Mortality . 10 6 .3 1. infant mortality . 12 6 .3 .2 circulatory disease mortality . 12 6 .3 .3 cancer mortality . 12 6 .3 4. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality . 13 7 Health service provision in Leeds . 13 7 1. Acute and tertiary services . 13 7 .2 Primary care services . 13 7 .3 Other primary care services . 14 7 4. NHS Leeds community healthcare services . 14 7 5. Drug and alcohol treatment services . 15 8 Current pharmaceutical provision in Leeds . 15 9 Ward summary and profiles . 22 10 Current summary of identified pharmaceutical need . 23 11 Further possible pharmaceutical services in Leeds . 86 12 Conclusions . 89 13 Acknowledgments . 89 PNA development group . x Medical director /executive sponsor . x 12 References . 90 13 Appendices . 91 14 Glossary of terms/abbreviation .