Download (15MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE HAWAIIAN GAZETTE, 34Um-Iah,;

.ySi2i 4 2 sal'Vf JBIWIHJPI , ..- . j X. Ja.MiaMa aila.aV,Jille.ltaa THE ' HAWAIIAN GAZETTE era aleutrrj la JflHull t Tjpa, It I l la 3 u-a- t6-.v.,- v. ..,..,. I .. I t tt SWI a T. CRAWFORD It Uaea-tla- en. ,..., ,..! J a MACDOWEtL.' 34uM-iaH,;..- ,M - - i. ;j II t it Rw4.V ..- - i til 1 t QttlarH0i4aaa.,...,.. t 11 rt S9 5 GAZETTE, j THE ..! W ta eaf t t HAWAIIAN Tbtrl4tViaa IX BULL11S BIS ......I HTS 1SXO llaltatCVIaaia la oa TiivTklMl CVIaaia, It CO Stltiaw! ! 0t tVlawa . JW JalatlM0 af lfca. faria wan peeyaM ir aaa n aia A WEEKLY JOUEAL, DEYOTED TO HAWAIIAN PEOaBESS. al)M4 a .Itaeoaat tb tatea, wKk ar a ttaaataat Wlarft wtrceV. 3aswe prepaid. fcl.itlwata.wlirlat','l,",rtM,J- - . N. IMat 4iMtwaiaV .t aeaa.a!e ! - with pay lo, vr m aettta ' " t nr to. aim vJrt4 Ortmx I lite atv Post 05 ei!iig laeia. Taleetbrraiirrteitit atetaKMf rMnlUMiea. Rm Aarla aaatlUaat, ar aaa. VOL. XIY "o. 36.! HONOLULU, 1S7S. iSTo. entpttaaa taay be ta4a by baa a a. vta taa eai ! WEDKESBAT, SEPTEMBER 4, WHOLE 712. araitatHpa. or(v 1b JIBriaBu .BUSINESS NOTICES. BliSlXESS XOTlChS. BUSINESS NOTICES. INSURANCE NOTICES. INSL11ANCE NOTICES. FOUKIGN NOTIPES. Tu 3cirSj.w Sximss Aweaarra s bxw-tj,- B. B. AI J.. lUKTMXIX. lSKUY", Boston Board of I'aderwriters. Insurtmco Notice. wtlUtaa. ami T ttcana JeW Aa--ir e Jr AaWi. Kit Si$I. R.WT A EOUKRTOS, IibW. CtTII IS61XISS. 4 GK.VTS ftr tit llavtallaa UUuU. AHK.XT FMIl THE BKITlIt WILLIAMS. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Sol City of License Call Letters Freq

SOL CITY OF LICENSE CALL LETTERS FREQ AL Montgomery WTXK-FM 107.5-FM AL Montgomery WTXK-AM 1210-AM Al Roanoke WELR-FM 102.3-FM AL Roanoke WLWE-AM 1360-AM AL Roanoke WLWE-FM 94.7-FM AL Scottsboro WWIC-AM 1050 AM-AM AL Talladega WTDR-FM 92.7/99.3-FM AR Arkadelphia KDEL-FM 100.9-FM AR Conway KASR-FM 92.7-FM AZ Prescott KYCA-AM 1490-AM CA San Francisco KNBR-AM 1050-AM CA San Mateo KTCT-AM 1050-AM CO Burlington KNAB-FM 104.1-FM CO Burlington KNAB-AM 1140-AM CO Fort Morgan KCGC-FM 94.5-FM DC Washington Sirius-SAT 212-SAT DC Washington XM-SAT 209-SAT DC Washington WSPZ-AM 570-AM DE Dover WDOV-FM 1410-FM DE Dover WDSD-FM 94.7-FM FL Bartow WWBF-FM 102.9-FM FL Bartow WWBF-AM 1130-AM FL Cocoa Beach WMEL-AM 1300-AM FL Fort Meyers WWCN-FM 99.3-FM FL LIVE OAK WQHL-AM 1250-AM FL Live Oak WQHL-FM 98.1-FM GA Atlanta WGST-AM 640-AM GA Carrollton WBTR-FM 92.1-FM GA Clarkesville WDUN-FM 102.9-FM GA Dahlonega WZTR-FM 104.3-FM GA Gainesville WDUN-AM 550-AM GA LaGrange WLAG-AM 1240-AM GA LaGrange WLAG-FM 96.9-FM GA Zebulon WEKS-FM 92.5-FM IA Audubon KSOM-FM 96.5-FM IA Burlington KCPS-AM 1150-AM IA Cedar Rapids KGYM-FM 107.5-FM IA Cedar Rapids KGYM-AM 1600-AM IA Creston KSIB-FM 101.3-FM IA Creston KSIB-AM 1520-AM IA decorah KVIK-FM 104.7-FM IA Humboldt KHBT-FM 97.7-FM IA Iowa City KCJJ-AM 1630-AM IA Marshalltown KXIA-FM 101.1-FM IA Marshalltown KFJB-AM 1230-AM IA OSKALOOSA KBOE-AM 740-AM IA Oskaloosa KBOE-FM 104.9-FM IA Sioux City KSCJ-AM 1360-AM IL Bloomington WJBC-AM 1230-AM IL Champaign WDWS-AM 1400-AM IL Christopher WXLT-FM 103.5-FM IL Danville WDAN-AM 1490-AM -

No. 269 October 10

small screen News Digest of Australian Council on Children and the Media (incorporating Young Media Australia) ISSN: 0817-8224 No. 269 October 2010 Changes at ACCM The Australian Children’s Television Children lie to join Facebook Foundation (ACTF), the founding Present- Professor Elizabeth ing Partner of Trop Jr, is again providing Handsley was elect- According to Jim O’Rourke, writing in The support to the festival. ABC3, ABC TV’s ed President of the Age, children as young as 8 are signing up dedicated children’s digital channel, is the Australian Council to Facebook and exposing themselves to Major Media Partner. on Children and the cyber bullying and online predators. media at the Annual Entries close on 6 January and young film- General Meeting held Both police and teachers are warning makers can enter online. To be eligible, they on Tuesday 26 October parents to be more vigilant when it comes to will have to create a film that is no longer 2010. their children and Facebook. They say that than seven minutes long that must feature a growing number of children are flouting the Trop Jr Signature Item for 2011 – FAN Jane Roberts (WA) is the new Vice- the Facebook age restrictions and creating - to prove it was made for the festival President. We are happy to welcome new accounts despite the age requirement. Directors, Kym Goodes (Tasmania) and These children have to lie about their age http://www.tropjr.com.au Marjorie Voss (Queensland) . because users have to be over 13 to create a Facebook account and many parents are Rev Elisabeth Crossman (Qld), Anne Fit- unaware that this is happening. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

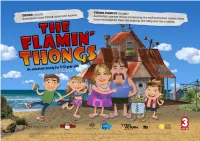

An Animated Comedy for 8-12 Year Olds 26 X 12Min SERIES

An animated comedy for 8-12 year olds 26 x 12min SERIES © 2014 MWP-RDB Thongs Pty Ltd, Media World Holdings Pty Ltd, Red Dog Bites Pty Ltd, Screen Australia, Film Victoria and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Whale Bay isis homehome toto thethe disaster-pronedisaster-prone ThongThong familyfamily andand toto Australia’sAustralia’s leastleast visitedvisited touristtourist attraction,attraction, thethe GiantGiant Thong.Thong. ButBut thatthat maymay bebe about to change, for all the wrong reasons... Series Synopsis ........................................................................3 Holden Character Guide....................................................4 Narelle Character Guide .................................................5 Trevor Character Guide....................................................6 Brenda Character Guide ..................................................7 Rerp/Kevin/Weedy Guide.................................................8 Voice Cast.................................................................................9 ...because it’s also home to Holden Thong, a 12-year-old with a wild imagination Creators ...................................................................................12 and ability to construct amazing gadgets from recycled scrap. Holden’s father Director’s‘ Statement..........................................................13 Trevor is determined to put Whale Bay on the map, any map. Trevor’s hare-brained tourist-attracting schemes, combined with Holden’s ill-conceived contraptions, -

PRODUCTION SERVICES 40050265 PRINTED40050265 in USPS CANADA Approved Polywrap AFSM 100 NUMBER AGREEMENT POST NUMBER CANADA Contents DECEMBER 2010

DECEMBER 2010 ’S FOCUS ON PRODUCTION SERVICES 40050265 PRINTED40050265 IN USPS CANADA Approved Polywrap AFSM 100 NUMBER NUMBER CANADA POST AGREEMENT POST CANADA Contents DECEMBER 2010 7Animation 14Talent 19Audio Innovative service providers are Tips on tracking down magic- When it comes to setting a series’ keeping costs down and moving making writing and acting talent to tone, music choice and sound tech forward in this global market elevate a concept from good to great design speak volumes 29Post 33 Interactive 37Distribution Budgets may be tighter, but A digital extension is no longer an The migration to digital delivery producers can’t afford to overlook add-on, but a necessity—and so is is pushing distributors into self- the fi nishing touches fi nding the right interactive partner service territory 2 DECEMBER 2010 ’S FOCUS ON PRODUCTION SERVICES KS.18339.Toonbox.indd 1 11/11/10 3:56 PM Editor’s note December 2010 • Volume 15, Issue 8 all know the whole is only as good as the We VP & PUBLISHER sum of its parts, and that adage certainly holds true Jocelyn Christie ([email protected]) when it comes to children’s entertainment. While EDITORIAL getting a series greenlit continues to be challenging, Lana Castleman Editor ([email protected]) arguably the real panic sets in when a producer sits Kate Calder Senior Writer ([email protected]) Gary Rusak Senior Writer ([email protected]) back with presales and a delivery schedule in-hand Wendy Goldman Getzler Senior Online Writer ([email protected]) and thinks, “Eek! Now What? -

KGO-AM, KNBR-AM, KNBR-FM, KSAN-FM, KSFO-AM, KTCT-AM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT August 1, 2019 - July 31, 2020

Page: 1/6 KGO-AM, KNBR-AM, KNBR-FM, KSAN-FM, KSFO-AM, KTCT-AM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT August 1, 2019 - July 31, 2020 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Sales Assistant 1-5, 7-10, 12-16, 18-23 21 Account Executive 1-5, 7-10, 12-23 21 Account Executive 1-5, 7-10, 12-23 21 Sales Assistant 1-5, 7-10, 12-15, 17-23 9 Sales Assistant 1-5, 7-10, 12-15, 17-23 9 KNBR Producer 1-15, 17-23 11 KNBR Producer 1-15, 17-23 11 Full Time Producer 1-10, 12-15, 17, 19-23 21 Accounts Receivable Specialist 1-10, 12-15, 17, 19-20, 22-23 9 Digital Project Manager 1-15, 17, 19-23 11 Web Content Producer 1-5, 7-9, 12-15, 17, 19-20, 22-23 9 This report was revised in July 2021 to address reporting issues Page: 2/6 KGO-AM, KNBR-AM, KNBR-FM, KSAN-FM, KSFO-AM, KTCT-AM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT August 1, 2019 - July 31, 2020 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") Source Entitled No. of Interviewees RS to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Number Notification? Over (Yes/No) Reporting Period Academy of Art University 79 New Montgomery St. 1 San Francisco, California 94105 N 0 Email : [email protected] Academic Career Center Arriba Juntos 1850 Mission St. 2 San Francisco, California 94103 N 0 Fax : 1-415-863-9314 Edwin Narvaez California Broadcasters Assoc. -

AM Nighttime Compatibility Study Report

AM Nighttime Compatibility Study Report May 23, 2003 iBiquity Digital Corporation 8865 Stanford Boulevard, Suite 202 20 Independence Boulevard Columbia, Maryland 21045 Warren, New Jersey 07059 (410) 872-1530 (908) 580-7000 iBiquity Digital Corporation has prepared this report to analyze the impact of the introduction of nighttime AM IBOC broadcasting on existing analog AM service. It is a culmination of an extensive 12 month study of the interference in the nighttime band including work by Xetron Corp., which characterized the receivers and made recordings; the Advanced Television Technology Center (ATTC), which scored by Absolute Category Rating Mean Opinion Score (MOS)1 the recordings; Metker Radio Consulting, which generated the maps and ran the statistics based on the MOS and iBiquity Engineering, which developed the algorithms tying the MOS to coverage and managed the overall study. iBiquity’s previous reports on AM IBOC focused solely on daytime service. In order to address industry questions about the impact of IBOC on the more unpredictable AM nighttime environment, iBiquity undertook two initiatives. The first effort involved a detailed analytical study predicting IBOC interference from combined skywave and groundwave signals affecting analog AM groundwave nighttime service. This study determined the amount of impact IBOC would have on listener perception of analog AM in a station’s primary service area. The results of that study are detailed herein. The second effort involved nighttime field observations covering (i) digital groundwave interference into an analog skywave desired signal, (ii) digital skywave interference into an analog skywave desired signal and (iii) digital skywave interference into a groundwave desired signal. -

Broadcasting the BUSINESSWEEKLY of TELEVISION and RADIO

Oct. 21, 1968:Our 38th Year:5(X Broadcasting THE BUSINESSWEEKLY OF TELEVISION AND RADIO Spot TV sales up, may nudge $1 billion in '69. p23 Special report: The unanswered problems of TV. p36 It was a banner week in radio -TV station sales. p48 Round two in BMI rate increase battle to resume. p55 tAL s- K OBRAR Y, 5024.'-» Sold Sight Unseen this year Screen Gems released To date these specials have been sold New York, WBBM -TV Chicago, six hour -long color tape entertainment in more than 40 markets. KMOX -TV St. Louis, WCAU -TV Phila- specials-"SCREEN GEMS PRESENTS" This kind of performance calls for an delphia and KTLA Los Angeles, which -starring such great headliners encore ... and that's just what we plan: six were among the very first to license our as Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington, more great specials with another outstanding initial group of specials, have already Julie London, Jane Morgan and group of star performers. bought our second group -sight unseen! the Doodletown Pipers, Gordon MacRae, As quick as you could say Jackie Obviously, one good turn deserves another. Shirley Bassey and Polly Bergen. Barnett -he's our producer- WCBS-TV Screen Gems Banker, broker, railroad man, grocer, builder, librarian, fireman, mayor, nurse, police, doctor, lawyer, No matter what your business, it involves moving information. Voice. Video. Or data. And nobody knows more about moving information than the people who run the largest information network in the world. The Bell System. That's why we keep a man on our payroll who specializes in your business. -

EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT August 1, 2020 - July 31, 2021

Page: 1/6 KGO-AM, KNBR-AM, KNBR-FM, KSAN-FM, KSFO-AM, KTCT-AM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT August 1, 2020 - July 31, 2021 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Digital Sales Specialist 1-7, 9, 11-22 21 VP/Market Manager 2-4, 6-7, 9, 11-14, 18-19, 21-22 21 Digital Designer 1-22 21 Page: 2/6 KGO-AM, KNBR-AM, KNBR-FM, KSAN-FM, KSFO-AM, KTCT-AM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT August 1, 2020 - July 31, 2021 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") Source Entitled No. of Interviewees RS to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Number Notification? Over (Yes/No) Reporting Period Academy of Art University 79 New Montgomery St. 1 San Francisco, California 94105 N 0 Email : [email protected] Academic Career Center Adzuna unknown 2 Indianapolis, Indiana N 0 Job Listing Manual Posting Arriba Juntos 1850 Mission St. 3 San Francisco, California 94103 N 0 Fax : 1-415-863-9314 Edwin Narvaez California Broadcasters Assoc. 915 "L" Street Suite #1150 Sacramento, California 95814 4 Phone : 916-444-2237 N 0 Url : http://www.yourcba.com Joe Berry Manual Posting City College of San Francisco 50 Phelan Ave. 5 San Francisco, California 94112 N 0 Email : [email protected] Career Center Experience Unlimited 745 Franklin St. Lower Level San Francisco, California 94102 6 Email : [email protected] N 0 Fax : 1-415-749-7478 Sylvia Gonzales Glass Door 100 Shoreline Hwy Bld. -

(“Agreement”) Covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS

INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT (“Agreement”) covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS TELEVISION PROGRAMS and OTHER PRODUCTION between The WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA (the “Guild”) and The CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION (“CMPA”) and ASSOCIATION QUÉBÉCOISE DE LA PRODUCTION MÉDIATIQUE (“AQPM”) (the “Associations”) March 16, 2015 to December 31, 2017 © 2015 WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA and CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION and the ASSOCIATION QUÉBÉCOISE DE LA PRODUCTION MÉDIATIQUE. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A: General – All Productions p. 1 Article A1 Recognition, Application and Term p. 1 Article A2 Definitions p. 4 Article A3 General Provisions p. 14 Article A4 No Strike and Unfair Declaration p. 15 Article A5 Grievance Procedures and Resolution p. 16 Article A6 Speculative Writing, Sample Pages and Unsolicited Scripts p. 22 Article A7 Copyright and Contracts; Warranties, Indemnities and Rights p. 23 Article A8 Story Editors and Story Consultants p. 29 Article A9 Credits p. 30 Article A10 Security for Payment p. 41 Article A11 Payments p. 43 Article A12 Administration Fee p. 50 Article A13 Insurance and Retirement Plan, Deductions from Writer’s Fees p. 51 Article A14 Contributions and Deductions from Writer’s Fees in the case of Waivers p. 53 Section B: Conditions Governing Engagement p. 54 Article B1 Conditions Governing Engagement for all Program Types p. 54 Article B2 Optional Bibles, Script/Program Development p. 60 Article B3 Options p. 61 Section C: Additional Conditions and Minimum Compensation by Program Type p. 63 Article C1 Feature Film p. 63 Article C2 Optional Incentive Plan for Feature Films p. 66 Article C3 Television Production (Television Movies) p.