Aufderheide Documentary Film Since 1999 Ssrn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Conversation with Adam Curtis, Part III Will Take Place As a Live Interview at E-Flux, New York, on April 14Th

Since the early 1990s Adam Curtis has made a number of serial documentaries and films for the BBC using a playful mix of journalistic reportage and a wide range of avant-garde filmmaking techniques. The films are linked through their interest in using and reassembling the fragments of the past – recorded on film and video―to try 01/13 and make sense of the chaotic events of the present. I first met Adam Curtis at the Manchester International Festival thanks to Alex Poots, and while Curtis himself is not an artist, many artists over the last decade have become increasingly interested in how his films break down the divide between art and modern political reportage, opening up a dialogue between the Hans Ulrich Obrist two. ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊThis multi-part interview with Adam Curtis began in London last December, and is the most In Conversation recent in a series of conversations published by e-flux journal that have included Raoul Vaneigem, with Adam Julian Assange, Toni Negri, and others, and I am pleased to present the second part in this issue of Curtis, Part II the journal in conjunction with a solo exhibition I have curated of Curtis’s films from 1989 to the present day. The exhibition is designed by Liam Gillick, and will be on view at e-flux in New York from February 11–April 14, 2012. In Conversation with Adam Curtis, Part III will take place as a live interview at e-flux, New York, on April 14th. – Hans Ulrich Obrist ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊ ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊ→ Continued from “In Conversation with Adam Curtis, Part I.” ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊ ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊHUO: I wanted to ask you about collage, and t the way you use archival film footage as a s i r b storytelling technique, but also as a way of O h revisiting the recent past. -

The American Nightmare, Or the Revelation of the Uncanny in Three

The American Nightmare, or the Revelation of the Uncanny in three documentary films by Werner Herzog La pesadilla americana, o la revelación de lo extraño en tres documentales de DIEGO ZAVALA SCHERER1 Werner Herzog http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7362-4709 This paper analyzes three Werner Herzog’s films: How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck (1976), Huie’s Sermon (1981) and God´s Angry Man (1981) through his use of the sequence shot as a documentary device. Despite the strong relation of this way of shooting with direct cinema, Herzog deconstructs its use to generate moments of filmic revelation, away from a mere recording of events. KEYWORDS:Documentary device, sequence shot, Werner Herzog, direct cinema, ecstasy. El presente artículo analiza tres obras de la filmografía de Werner Herzog: How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck (1976), Huie´s Sermon (1981) y God´s Angry Man (1981), a partir del uso del plano secuencia como dispositivo documental. A pesar del vínculo de esta forma de puesta en cámara con el cine directo, Herzog deconstruye su uso para la generación de momentos de revelación fílmica, lejos del simple registro. PALABRAS CLAVE: Dispositivo documental, plano secuencia, Werner Herzog, cine directo, éxtasis. 1 Tecnológico de Monterrey, México. E-mail: [email protected] Submitted: 01/09/17. Accepted: 14/11/17. Published: 12/11/18. Comunicación y Sociedad, 32, may-august, 2018, pp. 63-83. 63 64 Diego Zavala Scherer INTRODUCTION Werner Herzog’s creative universe, which includes films, operas, poetry books, journals; is labyrinthine, self-referential, iterative … it is, we might say– in the words of Deleuze and Guattari (1990) when referring to Kafka’s work – a lair. -

An Anguished Self-Subjection: Man and Animal in Werner Herzog's Grizzly

An Anguished Self-Subjection: Man and Animal in Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man Stefan Mattessich Santa Monica College Do we not see around and among us men and peoples who no longer have any essence or identity—who are delivered over, so to speak, to their inessentiality and their inactivity—and who grope everywhere, and at the cost of gross falsifications, for an inheritance and a task, an inheritance as task? Giorgio Agamben The Open erner herzog’s interest in animals goes hand in hand with his Winterest in a Western civilizational project that entails crossing and dis- placing borders on every level, from the most geographic to the most corporeal and psychological. Some animals are merely present in a scene; early in Fitzcarraldo, for instance, its eponymous hero—a European in early-twentieth-century Peru—plays on a gramophone a recording of his beloved Enrico Caruso for an audience that includes a pig. Others insist in his films as metaphors: the monkeys on the raft as the frenetic materializa- tion of the conquistador Aguirre’s final insanity. Still others merge with characters: subtly in the German immigrant Stroszek, who kills himself on a Wisconsin ski lift because he cannot bear to be treated like an animal anymore or, literally in the case of the vampire Nosferatu, a kindred spirit ESC 39.1 (March 2013): 51–70 to bats and wolves. But, in every film, Herzog is centrally concerned with what Agamben calls the “anthropological machine” running at the heart of that civilizational project, which functions to decide on the difference between man and animal. -

L'invention Musicale Face À La Nature Dans Grizzly

L’invention musicale face à la nature dans Grizzly Man, The Wild Blue Yonder et La grotte des rêves perdus de Werner Herzog Vincent Deville To cite this version: Vincent Deville. L’invention musicale face à la nature dans Grizzly Man, The Wild Blue Yonder et La grotte des rêves perdus de Werner Herzog. Revue musicale OICRM, Observatoire interdisciplinaire de création et de recherche en musique, 2018, 5 (n°1), s.p. hal-02133197v1 HAL Id: hal-02133197 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02133197v1 Submitted on 17 May 2019 (v1), last revised 15 Jul 2019 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License L’invention musicale face à la nature dans Grizzly Man, The Wild Blue Yonder et La grotte des rêves perdus de Werner Herzog Vincent Deville Résumé Quand le cinéaste allemand Werner Herzog réalise ou produit trois documentaires sur la création et l’enregistrement de la musique de trois de ses films entre 2005 et 2011, il effectue un double geste de révélation et d’incarnation : les notes nous deviennent visibles à travers le corps des musiciens. -

Islamic Movements Syllabus

Islamic Movements Tugrul Keskin Portland State University 1. Course Overview This course will review and analyze the increasing trend of Islamic movements (IM) and Islamic parties (IP) around the world in the global age of capitalism and the contemporary Muslim world. In the course, we focus on IM and IP and their relationship with global capitalism, democracy, free speech, human rights, inequality, colonialism/imperialism, modernity, secularism and governance. All of these concepts are directly related with the conditions of modernity which have been created by the free market economy; therefore, I perceive Political Islam (IM and IP) as a product of modern conditions, such as urbanization, the emergence of a manufacture-based economy, the increased availability of higher education, women’s participation in education and the workforce, and the elimination of traditional social values. The conditions of modernity created the concept of democracy in the modern world. Christianity and Judaism have consequently been struggling to redefine themselves under the new rules and regulations – not revelations - for over 200 years; whereas in Muslim Societies, the conditions of modernity challenge Islam and Muslims. Therefore, Muslims will be forced to decide between the expression and practice of Din/Religion and the material world in their daily life. There is therefore an ongoing struggle between the observance of God and the pursuit of material conditions. Although Political Islam could be seen as a direct reaction to modern politics, Islam is actually an inherently political religion that rules and regulates every aspect of a believer’s daily life, much in the same way as economic conditions do. -

Mediated Meetings in Grizzly Man

An Argument across Time and Space: Mediated Meetings in Grizzly Man TRENT GRIFFITHS, Deakin University, Melbourne ABSTRACT In Werner Herzog’s 2005 documentary Grizzly Man, charting the life and tragic death of grizzly bear protectionist Timothy Treadwell, the medium of documentary film becomes a place for the metaphysical meeting of two filmmakers otherwise separated by time and space. The film is structured as a kind of ‘argument’ between Herzog and Treadwell, reimagining the temporal divide of past and present through the technologies of documentary filmmaking. Herzog’s use of Treadwell’s archive of video footage highlights the complex status of the filmic trace in documentary film, and the possibilities of documentary traces to create distinct affective experiences of time. This paper focuses on how Treadwell is simultaneously present and absent in Grizzly Man, and how Herzog’s decision to structure the film as a ‘virtual argument’ with Treadwell also turns the film into a self-reflexive project in which Herzog reconsiders and re-presents his own image as a filmmaker. With reference to Herzog’s notion of the ‘ecstatic truth’ lying beneath the surface of what the documentary camera records, this article also considers the ethical implications of Herzog’s use of Treadwell’s archive material to both tell Treadwell’s story and work through his own authorial identity. KEYWORDS Documentary time, self-representation, digital film, trace, authorship, Werner Herzog. Introduction The opening scene of Grizzly Man (2005), Werner Herzog’s documentary about the life and tragic death of grizzly bear protectionist and amateur filmmaker Timothy Treadwell, shows Treadwell filming himself in front of bears grazing in a pasture, addressing the camera as though a wildlife documentary presenter. -

The Power of Nightmares - the Rise of the Politics of Fear Transcript by Vaara of Episode 1, “Baby It’S Cold Outside”

The Power of Nightmares - The Rise of the Politics of Fear Transcript by vaara of Episode 1, “Baby It’s Cold Outside”. Episode 2 and 3. [View the stream; listen to the audio; watch and download through Google video]. Originally aired on BBC 2, 20 October 2004, 9 pm. Written and Produced by Adam Curtis. VO: In the past, politicians promised to create a better world. They had different ways of achieving this. But their power and authority came from the optimistic visions they offered to their people. Those dreams failed. And today, people have lost faith in ideologies. Increasingly, politicians are seen simply as managers of public life. But now, they have discovered a new role that restores their power and authority. Instead of delivering dreams, politicians now promise to protect us from nightmares. They say that they will rescue us from dreadful dangers that we cannot see and do not understand. And the greatest danger of all is international terrorism. A powerful and sinister network, with sleeper cells in countries across the world. A threat that needs to be fought by a war on terror. But much of this threat is a fantasy, which has been exaggerated and distorted by politicians. It’s a dark illusion that has spread unquestioned through governments around the world, the security services, and the international media. VO: This is a series of films about how and why that fantasy was created, and who it benefits. At the heart of the story are two groups: the American neoconservatives, and the radical Islamists. Both were idealists who were born out of the failure of the liberal dream to build a better world. -

Camus' Catch: How Democracies Can Defeat Totalitarian Political Islam

Camus’ Catch: How democracies can defeat Totalitarian Political Islam Alan Johnson Editor’s Note: This is a version of a speech given at a conference organised by MedBridge Strategy Center, Camus: Moral Clarity in an Age of Terror, in Paris, 25 February, 2006. …the Cold War was fought with not only weapons that were military or intelligence based; it was fought through newspapers, journals, culture, the arts, literature. It was fought not just through governments but through foundations, trusts, civil society and civic organisations. Indeed we talked of a cultural Cold War – a Cold War of ideas and values – and one in which the best ideas and values eventually triumphed. And it is by power of argument, by debate and by dialogue that we will, in the long term, expose and defeat this extremist threat and we will have to argue not just against terrorism and terrorists but openly argue against the violent perversion of a peaceful religious faith. it is … necessary to take these ideas head on – a global battle for hearts and minds, and that will mean debate, discussion and dialogue through media, culture, arts, and literature. And not so much through governments, as through civil society and civic culture – in partnership with moderate Muslims and moderates everywhere – as globally we seek to isolate extremists from moderates. (Gordon Brown, British Chancellor of the Exchequer, February 13 2006) I speak today from the democratic left and, mainly, about the left. But I am seeking interlocutors from, and alliances with, the much wider set of democratic and liberal traditions represented at this conference. -

7 the Politics of Affect in Activist Amateur Subtitling a Biopolitical Perspective

7 The politics of affect in activist amateur subtitling A biopolitical perspective Luis Pérez-González Self-mediated audiovisual content produced by ordinary citizens on dig- ital media platforms reveals interesting aspects of the negotiation of affi nity and antagonism among members of virtual transnational constit- uencies. Based on Pratt’s (1987) conceptualization of contact zones, this chapter examines the role played by communities of activist subtitlers – characterized here as emerging agents of political intervention in public life – in facilitating the transnational fl ow of self-mediated textualities. I argue that by contesting the harmonizing pressure of corporate media structures and maximizing the visibility of non-hegemonic voices within mainstream-oriented audiovisual cultures, activist subtitling collectivi- ties typify the ongoing shift from representative to deliberative models of public participation in post-industrial societies. The chapter also engages with the centrality of affect – conceptualized from the disciplinary stand- point of biopolitics ( Foucault 2007 , 2008 ) – as a mobilizing force that fosters inter-subjectivity within and across radical subtitling collectivities. Drawing on an example of how emotions reverberate within a virtual community of amateurs subtitling the controversial BBC documentary The Power of Nightmares into Spanish, I examine how affect is gener- ated by the practices surrounding the production and reception of subti- tled material, and how the circulation fl ows of content through digital communication systems contribute to assembling an audience of affec- tive receptivity. Self-mediation, understood as the participation of ordinary people in public culture and politics by means of assembling and distributing digital media representations of their experiences ( Chouliaraki 2010 ), is foregrounding new forms of citizen engagement with public communication as a site of negotiation between the individual and the social. -

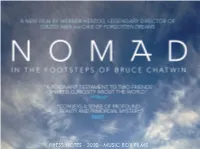

Bruce Chatwin, a Kindred Spirit Who Dedicated His Life to Illuminating the Mysteries of the World

PRESS NOTES - 2020 - MUSIC BOX FILMS LOGLINE Werner Herzog travels the globe to reveal a deeply personal portrait of his friendship with the late travel writer Bruce Chatwin, a kindred spirit who dedicated his life to illuminating the mysteries of the world. SYNOPSIS Werner Herzog turns the camera on himself and his decades-long friendship with the late travel writer Bruce Chatwin, a kindred spirit whose quest for ecstatic truth carried him to all corners of the globe. Herzog’s deeply personal portrait of Chatwin, illustrated with archival discoveries, film clips, and a mound of “brontosaurus skin,” encompasses their shared interest in aboriginal cultures, ancient rituals, and the mysteries stitching together life on earth. WERNER HERZOG Werner Herzog was born in Munich on September 5, 1942. He grew up in a remote mountain village in Bavaria and studied History and German Literature in Munich and Pittsburgh. He made his first film in 1961 at the age of 19. Since then he has produced, written, and directed more than sixty feature- and documentary films, such as Aguirre der Zorn Gottes (AGUIRRE, THE WRATH OF GOD, 1972), Nosferatu Phantom der Nacht (NOSFERATU, 1978), FITZCARRALDO (1982), Lektionen in Finsternis (LESSONS OF DARKNESS, 1992), LITTLE DIETER NEEDS TO FLY (1997), Mein liebster Feind (MY BEST FIEND, 1999), INVINCIBLE (2000), GRIZZLY MAN (2005), ENCOUNTERS AT THE END OF THE WORLD (2007), Die Höhle der vergessenen Träume (CAVE OF FORGOTTEN DREAMS, 2010). Werner Herzog has published more than a dozen books of prose, and directed as many operas. Werner Herzog lives in Munich and Los Angeles. -

Complete Works Films

Complete works Films 2020 Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds 2019 Family Romance, LLC 2019 NOMAD – In the footsteps of Bruce Chatwin 2018 Meeting Gorbachev (co-director André Singer) 2017 Into the Inferno 2016 Salt and Fire 2016 Lo and Behold 2014 Queen of the Desert 2013 From One Second to the Next 2012/13 On Death Row I + II WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria www.wernerherzog.com 2011 Into the Abyss - A Tale of Death, a Tale of Life 2010 Ode auf den Morgen der Menschheit (Ode to the Dawn of Man) 2010 Die Höhle der vergessenen Träume (Cave of Forgotten Dreams) 2009 La Bohéme 2009 My Son My Son What Have Ye Done 2008 Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans 2007 Encounters at the End of The World 2006 Rescue Dawn 2005 The Wild Blue Yonder 2005 Grizzly Man 2004 The White Diamond 2003 Rad der Zeit (Wheel of Time) WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria www.wernerherzog.com 2002 Christ and Demons in New Spain 2001 Ten Thousand Years Older 2001 Pilgrimage 2000 Invincible 1999 Gott und die Beladenen (The Lord and the Laden) 1999 Mein liebster Feind (My Best Fiend) 1999 Schwingen der Hoffnung aka Julianes Sturz in den Dschungel (Wings of Hope) 1997 Little Dieter Needs to Fly 1995 Tod für fünf Stimmen (Death for Five Voices) 1994 Die Verwandlung der Welt in Musik (The Transformation of the World into Music) 1993 Glocken aus der Tiefe (Bells from the Deep) 1992 Lektionen in Finsternis (Lessons of Darkness) 1991 Film Lektionen (Film Lesson) WERNER HERZOG FILM GMBH Spiegelgasse 9 1010 Vienna / Austria -

Motifs of Fiction in Werner Herzog's Films Chantal Poch [email protected], Pompeu Fabra University

Inner and deeper: Motifs of fiction in Werner Herzog's films Chantal Poch [email protected], Pompeu Fabra University Volume 7.2 (2019) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI /cinej.2019.224 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract The emphasis on the mix of facts and inventions has prevailed in the studies about Bavarian director Werner Herzog’s treatment of fiction, leading to the same result again and again: for Herzog, poetic truth is more important than factual truth. But how can we go beyond this conclusion? This paper will try to open an alternative path of analysis more adequate to his philosophy of filmmaking, one that works through the detection of visual and narrative motifs in his films, thus searching the impact of Herzog’s idea of fiction into his poetics. Keywords: Werner Herzog; German Cinema; Motifs; Fiction; Ecstatic Truth New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Inner and deeper: Motifs of fiction in Werner Herzog's films Chantal Poch Introduction Asking ourselves about the nature of fiction in film brings up to the question whether this fiction acts as an opposite of truth or, indeed, as truth itself. Bavarian director Werner Herzog has built an entire oeuvre regarding this problem: from the blurry lines between his fictional movies and documentaries to the recurrent inclusion of false quotes and events on his scripts, all of his films seem to add something to the same direction: the confusion of fact and fiction.