THE INTERRUPTERS a Film by Steve James and Alex Kotlowitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MOHICAN NEWSNEWS the People of the Waters That Are Never Still

STOCKBRIDGE-MUNSEE COMMUNITY Band of Mohicans MOHICANMOHICAN NEWSNEWS The people of the waters that are never still Vol. XXVII No. 11 N8480 Moh He Con Nuck Road • Bowler, WI 54416 June 1, 2019 North Star Mohican Casino Resort’s 27th Year Holsey Key Note at WIEA and Burr is Teacher of the Year By Jeff Vele – Mohican News Editor This year the Wisconsin Indian Education Association (WIEA) Awards Banquet was held at the Hotel Mead and Conference Center in Wisconsin Rapids, WI. The theme this year was “12 Nations, 2 Worlds, 1 People”. The Stockbridge-Munsee Community was well represented at the conference with President Shannon Holsey as the keynote speaker and several people from North Star Mohican Casino Resort general manager Michael Bonakdar, the area being recognized at the center, cuts into a cake for the resort’s 27th anniversary. (L to R):Terrance Indian Educator of the Year is Ms. awards banquet at the end of the Lucille Burr Stockbridge–Munsee Miller, Tammy Wyrobeck, Jachim Jaddoud, Bonakdar, Kirsten Holland, event, including Lucille Burr being and Brian Denny. Casino continued on page Four: Community Tribal member and, recognized as Teacher of the Year. Title VI Teacher, Shawano School District Whose homeland is the Mohawk Trail? President Holsey addressed a those advertised today to tourists roomful of teachers, students and you are really, truly the people coming to the Berkshires. family members, and educational that educate our children. It is so They hiked the woods and hunted leaders. Holsey started by saying, important to support you, as we black bear, deer and turkey. -

International Documentary Association Film Independent Independent Filmmaker Project Kartemquin Educational Films, Inc

Before the United States Copyright Office Library of Congress ) ) In the Matter of ) ) Docket No. 2012-12 Orphan Works and Mass Digitization ) ) COMMENT OF INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTARY ASSOCIATION FILM INDEPENDENT INDEPENDENT FILMMAKER PROJECT KARTEMQUIN EDUCATIONAL FILMS, INC. NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MEDIA ARTS AND CULTURE MARJAN SAFINIA / MERGEMEDIA KAREN OLSON / SACRAMENTO VIDEO INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS GILDA BRASCH KELLY DUANE DE LA VEGA / LOTERIA FILMS GEOFFREY SMITH / EYE LINE FILMS ROBERTO HERNANDEZ KATIE GALLOWAY Submitted By: Jack I. Lerner Michael C. Donaldson USC Intellectual Property and Donaldson & Callif, LLP Technology Law Clinic 400 South Beverly Drive University of Southern California Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Gould School of Law 699 Exposition Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90089 With the participation of clinical interns Minku Kang and Christopher Mastick February 4, 2013 In the Matter of Orphan Works and Mass Digitization, No. 2012-12 Comment of International Documentary Association et al. Page 2 of 15 I. INTRODUCTION The International Documentary Association, Film Independent, the Independent Filmmaker Project, Kartemquin Educational Films, Inc., the National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture, Gilda Brasch, Kelly Duane de la Vega of Loteria Films, Katie Galloway, Roberto Hernandez, Karen Olson of Sacramento Video Industry Professionals, Marjan Safinia of Merge Media, and Geoffrey Smith of Eye Line Films respectfully submit this comment on behalf of thousands of documentary and independent filmmakers and other creators who struggle every day with the orphan works problem. This problem effectively prevents filmmakers from licensing third party materials whenever the rightsholder cannot be identified or found; for many filmmakers, the threat of a lawsuit, crippling damages, and an injunction makes the risk of using an orphan work just too high. -

Julia Reichert and the Work of Telling Working-Class Stories

FEATURES JULIA REICHERT AND THE WORK OF TELLING WORKING-CLASS STORIES Patricia Aufderheide It was the Year of Julia: in 2019 documentarian Julia Reichert received lifetime-achievement awards at the Full Frame and HotDocs festivals, was given the inaugural “Empowering Truth” award from Kartemquin Films, and saw a retrospec- tive of her work presented at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (The International Documentary Association had already given her its 2018 award.) Meanwhile, her newest work, American Factory (2019)—made, as have been all her films in the last two decades, with Steven Bognar—is being championed for an Academy Award nomination, which would be Reichert’s fourth, and has been picked up by the Obamas’ new Higher Ground company. A lifelong socialist- feminist and self-styled “humanist Marxist” who pioneered independent social-issue films featuring women, Reichert was also in 2019 finishing another film, tentatively titled 9to5: The Story of a Movement, about the history of the movement for working women’srights. Yet Julia Reichert is an underrecognized figure in the contemporary documentary landscape. All of Reichert’s films are rooted in Dayton, Ohio. Though periodically rec- ognized by the bicoastal documentary film world, she has never been a part of it, much like her Chicago-based fellow Julia Reichert in 2019. Photo by Eryn Montgomery midwesterners: Kartemquin Films (Gordon Quinn, Steve James, Maria Finitzo, Bill Siegel, and others) and Yvonne 2 The Documentary Film Book. She is absent entirely from Welbon. 3 Gary Crowdus’s A Political Companion to American Film. Nor has her work been a focus of very much documentary While her earliest films are mentioned in many texts as scholarship. -

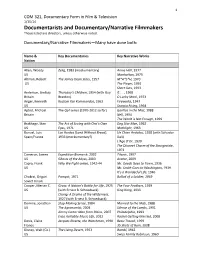

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

Lonely Soldiers: Women at War in Iraq a Regional Premiere by Helen Benedict March 16 – April 6, 2014

Play Guide Lonely Soldiers: Women at War in Iraq A regional premiere by Helen Benedict March 16 – April 6, 2014 1 History Theatre 30 East Tenth Street Saint Paul, MN 55101 Box Office: 651.292.4323 Group Sales: 651.292.4320 www.HistoryTheatre.com Table of Contents Summary of the Play* ............................................................................................ 3 About the author – Helen Benedict* ...................................................................... 3 The World of the Play: Military Ranks and Organization ....................................... 4 The World of the Play: Women in the Military* ...................................................... 5 Timeline of Women in the Military .......................................................................... 6 Sexual Assault in the Military* ................................................................................ 9 Activities • Small Group Discussion / Classroom Discussion .................................... 12 • What is Sexual Harassment? ................................................................... 13 • Sexual Harassment .................................................................................. 14 • Sexual Harassment vs. Flirting................................................................. 16 For Further Research and Suggested Reading* ................................................. 18 Help Lines, Websites, and Resources ................................................................. 20 *Material provided by Laura Weber. Play -

Deepa Mehta (See More on Page 53)

table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Experimental Cinema: Welcome to the Festival 3 Celluloid 166 The Film Society 14 Pixels 167 Meet the Programmers 44 Beyond the Frame 167 Membership 19 Annual Fund 21 Letters 23 Short Films Ticket and Box Offce Info 26 Childish Shorts 165 Sponsors 29 Shorts Programs 168 Community Partners 32 Music Videos 175 Consulate and Community Support 32 Shorts Before Features 177 MSPFilm Education Credits About 34 Staff 179 Youth Events 35 Advisory Groups and Volunteers 180 Youth Juries 36 Acknowledgements 181 Panel Discussions 38 Film Society Members 182 Off-Screen Indexes Galas, Parties & Events 40 Schedule Grid 5 Ticket Stub Deals 43 Title Index 186 Origin Index 188 Special Programs Voices Index 190 Spotlight on the World: inFLUX 47 Shorts Index 193 Women and Film 49 Venue Maps 194 LGBTQ Currents 51 Tribute 53 Emerging Filmmaker Competition 55 Documentary Competition 57 Minnesota Made Competition 61 Shorts Competition 59 facebook.com/mspflmsociety Film Programs Special Presentations 63 @mspflmsociety Asian Frontiers 72 #MSPIFF Cine Latino 80 Images of Africa 88 Midnight Sun 92 youtube.com/mspflmfestival Documentaries 98 World Cinema 126 New American Visions 152 Dark Out 156 Childish Films 160 2 welcome FILM SOCIETY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S WELCOME Dear Festival-goers… This year, the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival celebrates its 35th anniversary, making it one of the longest-running festivals in the country. On this occasion, we are particularly proud to be able to say that because of your growing interest and support, our Festival, one of this community’s most anticipated annual events and outstanding treasures, continues to gain momentum, develop, expand and thrive… Over 35 years, while retaining a unique flavor and core mission to bring you the best in international independent cinema, our Festival has evolved from a Eurocentric to a global perspective, presenting an ever-broadening spectrum of new and notable film that would not otherwise be seen in the region. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415-356-8383 x 244 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] For downloadable images, visit itvs.org/pressroom/photos/ For the program companion website, visit pbs.org/independentlens/stemcell/ MAPPING STEM CELL RESEARCH: Terra Incognita TO HAVE ITS BROADCAST PREMIERE ON THE EMMY® AWARD-WINNING PBS SERIES INDEPENDENT LENS ON TUESDAY, JANUARY 15, 2008 From Kartemquin Films (Hoop Dreams, THE NEW AMERICANS), New Documentary Puts a Human Face on the Stem Cell Controversy (San Francisco, CA)—It is one of the most controversial issues of our time, one that is sure to be a major part of the upcoming political debates. MAPPING STEM CELL RESEACH: Terra Incognita goes beyond the rhetoric to put a human face on the issue, introducing viewers to doctors, researchers and patients on the front lines. Directed by Maria Finitzo and produced by the award-winning Kartemquin Films (Hoop Dreams, Independent Lens’ THE NEW AMERICANS), MAPPING STEM CELL RESEACH: Terra Incognita will air nationally on the PBS series Independent Lens, hosted by Terrence Howard, on Tuesday, January 15, 2008 at 10:00 PM (check local listings). MAPPING STEM CELL RESEACH: Terra Incognita tells the story of Dr. Jack Kessler, the current chair of Northwestern University's Department of Neurology and Clinical Neurological Sciences, and his daughter, Allison, an undergraduate student at Harvard University. When Kessler was invited to head up the Neurology Department at Northwestern, his focus was on using stem cells to treat the neurological complications of diabetes. -

Starz’S €˜America to Me’ Docuseries Explores Race in Schools

Starz’s ‘America to Me’ Docuseries Explores Race in Schools 06.29.2018 Filmmaker Steve James (Hoop Dreams, The Interrupters, Life Itself, Abacus: Small Enough to Jail) spent a year inside suburban Chicago's Oak Park and River Forest High School, exploring the grapple with decades-long racial and educational inequities. America to Me follows students, teachers and administrators at one of the country's highest performing and diverse public schools, digging into many of the stereotypes and challenges that today's teenagers face, and looking at what has succeeded and failed in the quest to achieve racial equality in our educational system. The 10-part series also serves as the launch of a social impact campaign focusing on the issues highlighted in each episode. Starz partnered with series producer Participant Media to encourage candid conversations about racism through a downloadable Community Conversation Toolkit and elevate student voices through a national spoken-word poetry contest. Alongside the release of each new episode, the campaign will also host a high-profile screening event in one city across the country. Over the course of 10 weeks, these 10 events will seed a national dialogue anchored by the series, and kick off activities across the country to inspire students, teachers, parents and community leaders to develop local initiatives that address inequities in their own communities, says Starz. James directed and executive produced the series, along with executive producers Gordon Quinn (The Trials of Muhammad Ali), Betsy Steinberg (Edith+Eddie) and Justine Nagan (Minding the Gap) at his longtime production home, Kartemquin Films. -

A 2016 Documentary Film by Dinesh Das Sabu And

Unbroken Glass unbrokenglassfilm.com | facebook.com/unbrokenglass | @unbrokenglass A 2016 documentary film by Dinesh Das Sabu and Kartemquin Films Unbroken Glass is a documentary about filmmaker Dinesh Das Sabu's journey to understand his parents, who died 20 years ago when he was just six years old. Traveling to India and across the United States, Dinesh pieces together the story of his mother's schizophrenia and suicide, and how his family dealt with it in an age and culture where mental illness was often misunderstood, scorned and taboo. Unbroken Glass weaves together Dinesh’s journey of discovery with cinema-verite scenes of his family dealing with still raw emotions and consequences of his immigrant parents’ lives and deaths. Dinesh hopes that telling this story will raise awareness and reduce the stigma of mental illness, while at the same time empower suicide survivors and families of the mentally ill to share their stories. Unbroken Glass is Dinesh’s first feature film for Kartemquin Films. A graduate of University of Chicago, Dinesh is an independent documentary filmmaker. His work includes shooting part of Kartemquin’s American Arab and The Homestretch, as well as cinematography for Waking in Oak Creek, How to Build a School in Haiti and the forthcoming End of Love. In fall 2016, the team behind UNBROKEN GLASS is launching a robust community outreach campaign to screen the film and host discussions nation-wide. If you would like to schedule a screening, please contact [email protected]. The film is funded in part by the Sage Foundation, Firelight Media and the Asian Giving Circle.. -

The New Americans

TELEVISUALISING TRANSNATIONAL MIGRATION: THE NEW AMERICANS Alan Grossman and Áine O’Brien TELEVISUALISING TRANSNATIONAL MIGRATION: THE NEW AMERICANS Alan Grossman and Áine O’Brien Originally published in 2007: Grossman and O'Brien (eds) Projecting Migration: Transcultural Documentary Practice, Columbia University Press, NY (Book/DVD). [Combined DVD/Book engaged with questions of migration, mobility and displacement through the prism of creative practice. Columbia University Press, NY] I The title of this book [The New Americans] and the documentary series upon which it reflects proclaims that something is fundamentally different about our most recent wave of immigration The racial and ethnic identity of the United States is ‐ once again ‐ being remade. The 2000 Census counts some 28 million first‐generation immigrants among us. This is the highest number in history – often pointed out by anti‐immigrant lobbyists ‐ but it is not the highest percentage of the foreign‐born in relation to the overall population. In 1907, that ratio was 14 percent; today, it is 10 percent. Yet there is the pervasive notion that something is occurring that has never occurred before, or that more is at stake than ever before. And there is a crucial distinction to be made between the current wave and the ones that preceded it. As late as the 1950s, two‐thirds of immigration to the US originated in Europe. By the 1980s, more than 80 percent came from Latin America and Asia. As at every other historical juncture, when we receive a new batch of strangers, there is a reaction, a kind of political gasp that says: We no longer recognize ourselves. -

Are We Green Yet? Sustainability Takes Root in Our Intellectual Culture P

University Magazine Spring 2015 ST.LAWRENCE Are We Green Yet? SUSTAINABILITY TAKES ROOT IN OUR INTELLECTUAL CULTURE P. 16 ST. LAWRENCE UNIVERSITY | SPRING 2015 Spring,15 Features Nowadays, when we ask ourselves “Are We Green Yet?” we’re 16 talking about a lot more than just energy consumption. SLU Connect-DC may be “One Small Step Inside the Beltway” 24 for our students, but we’re betting it will lead to many giant leaps. As her graduation looms, a stellar student-athlete probes what makes 26 her think “There’s Something About This Place.” He’s an actor, a philanthropist and a distinguished Laurentian. 30 That’s what we say when “Introducing Kirk Douglas Hall.” Departments In Every Issue 4 On Campus 2 A Word from the President You might say these are 12 Sports 3 Letters St. Lawrence’s representatives in Congress. They’re the 32 Philanthropy in Action 41 First-Person students who participated in 37 Laurentian Portraits 42 Class Notes the University’s inaugural SLU 40 On Social Media 81 From the Archives Connect-DC program in January. One of them, Mariah Dignan ’15, On the Cover: Sustainability at St. Lawrence is a work in progress, and illustrator Edmon de Haro far right, tells us more on page JEFF MAURITZEN © demonstrates that it’s becoming part of our cerebral DNA—as well as part of our pipes and groundskeeping. 24. And if what she predicts : Above: Alexander Kusak ’12 captured this shot of a trio of Denmark Program students in Copenhagen. proves true, you may see her SITE Margot Nitschke ’16, center, describes how Denmark incorporates sustainability into its national life; page 20. -

Theinterruptersv10.Pdf

Presented by Kartemquin Films THE INTERRUPTERS • COMMUNITY RESOURCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Film | 1 How To Use The Film and Resource Guide | 2 Character Profiles | 3 Laying the Groundwork for Dialogue | 4 Discussion Questions | 5 5 Things You Can Do Today | 7 Online Resource List | 8 About Kartemquin Films | 10 Credits and Funders | 10 THE INTERRUPTERS • COMMUNITY RESOURCE GUIDE ABOUT THE FILM During one weekend in 2008, 37 people were shot in Chicago, seven of them fatally. It was the year Chicago became the emblem of America’s inner-city violence and gang problem. The Interrupters is the moving story of three dedicated “violence interrupters”—Ameena Matthews, Cobe Williams and Eddie Bocanegra—who, with bravado, humility and even humor, work to protect their Chicago communities from the violence they themselves once employed. Their work and their insights are informed by their own journeys, which, as each of them points out, defy easy characterization. From acclaimed producer-director Steve James (Hoop Dreams) and best-selling author-turned-producer Alex Kotlowitz (There Are No Children Here), The Interrupters is an unusually intimate journey into the stubborn persistence of violence in our cities. The New York Times says the film “has put a face to a raging epidemic and an unforgivable American tragedy.” Tio Hardiman created the “Violence Interrupters Program” for an innovative organization. CeaseFire, which is the brainchild of epidemiologist Gary Slutkin, who for 10 years battled the spread of cholera and AIDS in Africa. Slutkin believes that the spread of violence mimics that of infectious diseases, and so the treatment should be similar: Go after the most infected, and stop the infection at its source.