Mancini Sample.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Mancini Fellowship Official Award Rules

The ASCAP Foundation Henry Mancini Music Fellowship The specific rules and requirements of The ASCAP Foundation Henry Mancini Music Fellowship (the “Award”), including but not limited to, eligibility, winner selection process, and award criteria, are set forth below (the “Award Requirements”). These Award Requirements are supplemented by the general rules and regulations attached as Schedule A (the “General Terms” and collectively with the “Award Requirements”, the “Official Rules”), which are incorporated by reference. By participating in the Award process, all entrants agree to be bound by these Official Rules and the decisions of The ASCAP Foundation (the “Foundation”) and the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (“ASCAP”), which are final and binding in all respects. To the extent not specifically defined below, all capitalized terms have the meaning set forth in the General Terms. About the Award Named for Henry Mancini, whose credits include acclaimed soundtracks such as Days of Wine and Roses and Breakfast at Tiffany's, this fellowship is generously funded by Ginny Mancini to honor the memory of her husband. This fellowship provides support for a composer, arranger, orchestrator who demonstrates talent and exceptional career potential participating in the ASCAP/Columbia University Film Scoring Workshop. The Award will be presented to one (1) aspiring film composer who will be participating in the 2020 ASCAP Columbia University Film Scoring Workshop, to be conducted during the Spring 2020 semester at Columbia University, New York City (the “Composers’ Workshop”). The recipient selected by the ASCAP Creative Services Executives in consultation with industry executives. Workshop meets once per week from late January until mid-April. -

Pre-Assessment

Name: _________________________________________________ Date: ____________________________ Film Music Unit Pretest 6th Grade Music Multiple Choice 1. What is a melody? a. The main line in music b. The background line in music c. A song that we sing d. The rhythmic drive in music. 2. The line of music associated with Luke Skywalker in the movie Star Wars is called a ___________________. a. Sequence b. Ostinato c. Leitmotif d. Melody 3. What was the first movie with an entire original score? a. Gone with the Wind b. King Kong c. Casablanca d. Star Wars 4. What year did synthesizers become introduced as a part of film music? a. 1958 b. 1968 c. 1978 d. 1980 True or False 5. Music was included as a part of film starting with the first motion picture. True False 6. Film composers are not always well-respected in their careers. True False 7. Film music is played by a symphony. True False 8. Ascending melodies are generally happy, while descending melodies are generally sad. True False Matching Match each film with the composer who wrote the film score. 9. ___________ Star Trek a) Hans Zimmer 10. ___________ Edward Scissorhands b) Jerry Goldsmith 11. ___________ Titanic c) Max Steiner 12. ___________ The Lion King d) Danny Elfman 13. ___________ The Pink Panther e) John Williams 14. ___________ King Kong f) James Horner 15. ___________ Star Wars g) Henry Mancini Name: _________________________________________________ Date: ____________________________ Fill in the Blank Insert the best word into each blank. Not all words will be used. character consonance dissonance geographic harmony historic piano tension timbre 16. -

HENRY MANCINI BIOGRAPHY Mancini Born 1924 in Cleveland

HENRY MANCINI BIOGRAPHY Mancini born 1924 in Cleveland ,Ohio, learnt flute and piano at a young age. After High School he attended Julliard School of Music in Manhattan NY.{we can assume he was a very competent player with ambitions} . In 1943 after 1 year there he was drafted into the Army. After the war he became the pianist and arranger for the Glenn Miller Band, led by Tex Beneke.He also studied serious composing with Ernst Krenek and Mario Castelnuovo‐Tedesco. It was this, as well as his passion for jazz and swing music , that saw him join Universal Studios music dept as a house composer writing for such hits as Creature from the Black Lagoon , It came from Outer Space , Tarantula, followed by The Glenn Miller Story, The Benny Goodman Story , and Orson Welles Touch of Evil. He left Universal Studios in 1958 , working as an independent writer. He soon established a working relationship with Producer Blake Edwards { see Peter Sellers movie with Goeffrey Rush for character insights} . This produced nearly 30 films, the first being a tv series titled Peter Gunn. Other movies include Breakfast at Tiffanys, Days of wine and Roses, Pink Panther et al, The Party. Also Hatari, Victor/Victoria. Interestingly, Alfred Hitchcock rejected and replaced his work on the 1972 film Frenzy. He wrote many scores to TV shows, themes and ads, he recorded over 90 albums in styles ranging from Big Band to Classical to Pop. He at the time revolutionised the use of jazz in romantic and orchestral film and TV scores. -

Beyond the Machine Photo by Claudio Papapietro

Beyond The Machine Photo by Claudio Papapietro Juilliard Scholarship Fund The Juilliard School is the vibrant home to more than 800 dancers, actors, and musicians, over 90 percent of whom are eligible for financial aid. With your help, we can offer the scholarship support that makes a world of difference—to them and to the global future of dance, drama, and music. Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard—including you. For more information please contact Tori Brand at (212) 799-5000, ext. 692, or [email protected]. Give online at giving.juilliard.edu/scholarship. The Juilliard School presents Center for Innovation in the Arts Edward Bilous, Founding Director Beyond the Machine 19.1 InterArts Workshop March 26 and 27, 2019, 7:30pm (Juilliard community only) March 28, 2019, 7pm Conversation with the artists, hosted by William F. Baker 7:30pm Performance Rosemary and Meredith Willson Theater The Man Who Loved the World Treyden Chiaravalloti, Director Eric Swanson, Actor John-Henry Crawford, Composer On film: Jared Brown, Dancer Sean Lammer, Dancer Barry Gans, Dancer Dylan Cory, Dancer Julian Elia, Dancer Javon Jones, Dancer Nicolas Noguera, Dancer Canaries Natasha Warner, Writer, Director, and Choreographer Pablo O'Connell, Composer Esmé Boyce, Choreographer Jasminn Johnson, Actor Gwendolyn Ellis, Actor Victoria Pollack, Actor Jessica Savage, Actor Phoebe Dunn, Actor David Rosenberg, Actor Intermission (Program continues) Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs -

100% Print Rights Administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH

100% Print Rights administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN *A BRIDGE TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS A CHANGE IS GONNA COME (from “ Malcolm X”) Words and Music by SAM COOKE A CHI (HURT) (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by JIMMIE CRANE and AL JACOBS A CHICKEN AIN’T NOTHING BUT A BIRD Words and Music by EMMETT ‘BABE’ WALLACE A DARK KNIGHT (from “ The Dark Knight ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER and JAMES HOWARD A HARD TEACHER (from “ The Last Samurai ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER A JOURNEY IN THE DARK (from “ The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring”) Music by HOWARD SHORE Lyrics by PHILIPPA BOYENS A MOTHER’S PRAYER (from “ Quest for Camelot ”) Words and Music by CAROLE BAYER SAGER and DAVID FOSTER *A WINDOW TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS ACCORDION JOE Music by CORNELL SMELSER Lyrics by PETER DALE WIMBROW ACES HIGH MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN AIN'T GOT NO (Excluding Europe) Music by GALT MACDERMOT Lyrics by JAMES RADO and GEROME RAGNI AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (from “ Ain’t Misbehavin’ ) (100% in Scandinavia, including Finland) Music by THOMAS “FATS” WALLER and HARRY BROOKS Lyrics by ANDY RAZAF ALL I DO IS DREAM OF YOU (from “ Singin’ in the Rain ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by NACIO HERB BROWN Lyrics by ARTHUR FREED ALL TIME HIGH (from “ Octopussy ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by JOHN BARRY Lyrics by TIM RICE ALMIGHTY GOD (from “ Sacred Concert No. -

Five Sax Booklet-Bl1457de 136X122mm 28-Seit Layout 1 24.02.15 13:48 Seite 1

RZ_or 0016-Five Sax_Booklet-BL1457de_136x122mm_28-seit_Layout 1 24.02.15 13:48 Seite 1 FIVE SAX at the Movies RZ_or 0016-Five Sax_Booklet-BL1457de_136x122mm_28-seit_Layout 1 24.02.15 13:48 Seite 2 FIVE SAX at the Movies Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897–1957) Ennio Morricone (*1928) John Williams (*1932) arr. Jacek Obstarczyk Klaus Badelt (*1967) from “The Mission” John Debney (*1956) arr. Jacek Obstarczyk 08 Gabriel’s Oboe 03:04 01 Pirates Medley 10:05 from “The Legend of 1900” 09 Playing Love 04:30 Leroy Shield (1893–1962) arr. Alberto di Priolo Incidental Music from “Laurel & Hardy” Michael Giacchino (*1967) 02 Cuckoo 00:34 arr. Alberto di Priolo 03 Colonial Gayeties 01:45 from “Up” 04 Cops 00:42 05 Little Dancing Girl 01:13 10 Married Life 04:13 06 We Are Out for Fun 00:59 Bernard Herrmann (1911–1975) Nino Rota (1911–1979) arr. Jacek Obstarczyk arr. Joel Diegert 11 Psycho Suite 05:59 07 8 Theme 04:29 ½ 2 RZ_or 0016-Five Sax_Booklet-BL1457de_136x122mm_28-seit_Layout 1 24.02.15 13:49 Seite 3 John Williams (*1932) Henry Mancini (1924–1994) arr. Jacek Obstarczyk arr. Joel Diegert & Alvaro Collao from “Harry Potter” from “The Pink Panther” 12 Hedwig’s Theme 04:06 15 The Pink Panther Theme 02:02 16 The Village Inn 01:24 17 Royal Blue 03:41 18 It Had Better Be Tonight 03:34 Howard Leslie Shore (*1946) arr. Joel Diegert & Jacek Obstarczyk TT 65:38 13 Lord of the Rings 08:58 Bono (*1960) & The Edge (*1961) arr. Alvaro Collao & Joel Diegert FIVE SAX JOEL DIEGERT – soprano, alto, baritone, bass saxophones 14 Golden Eye 04:18 MICHAL KNOT – alto, soprano, -

String Love Complete Song Lists

String Love Complete(ish) Song Lists Our repertoire is always growing, check back frequently! ROCK AND POP 1 2 3 4 – Plain White T’s 21 Guns – Green Day 100 Years – Five For Fighting A Thousand Years – Christina Perri Addicted To You - Avicii Adore You – Miley Cyrus Adventure of a Lifetime – Coldplay All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor All I Want Is You – U2 All My Love – Led Zeppelin All Of Me – John Legend All These Things That I’ve Done – The Killers All You Need Is Love – The Beatles American Idiot – Green Day Animals – Matthew Garrix Animaniacs – Rueger / Stone Annie’s Song – John Denver Ants Marching – Dave Matthews Band Applause – Lady Gaga Aqualung – Jethro Tull Atlas – Coldplay Back In Black – AC/DC Bang Bang – Jessie J The Battle Of Evermore – Led Zeppelin Beautiful Day – U2 Beautiful Life – Ace of Base Best Day Of My Life – American Authors Better Together – Jack Johnson Birthday – Katy Perry Bittersweet Symphony – The Verve Black Dog – Led Zeppelin Blackbird – The Beatles Blank Space – Taylor Swift Blue Tango – Leroy Anderson Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Boom Clap – Charli XCX Bridge Over Troubled Water – Simon and Garfunkle Bring Me To Life – Evanescence Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Burn – Ellie Goulding Can’t Help Falling In Love – Elvis Presley Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Can’t Take My Eyes Off You – Frankie Valli Candle In The Wind – Elton John Chandalier – Sia Chasing Cars – Snow Patrol Cheerleader – OMI Clocks – Coldplay Come Away With Me – Norah Jones Come On Eileen – Dexy’s Midnight Runners Cotton-Eyed -

Song Recital

SsacredONG and secular R Esongs C Iand TA opera L Inauguration of the Barbara Russell Memorial Piano Viewing of Violet Oakley’s Great Women of the Bible Murals Evelyn Santiago, soprano Margaret Mezzacappa, mezzo soprano Ted W. Barr, piano & Geraldine Rice, viola The Jennings Room Sunday Afternoon at 4 p.m. October 1, 2017 THE FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN GERMANTOWN The Barbara L. Russell Memorial Piano is the generous gift to First Church by her family. The Heintzman & Co. Louis XV style grand piano is a “one-of-a-kind” instrument built for the 1906 Canadian National Ex- hibition. It was purchased by Mrs. Russell’s great grandfather and passed down through the family. Barbara Russell, a beloved member of the Chestnut Hill community, enjoyed a national reputation for needlepoint; she had a shop on Germantown Avenue for 35 years. Mrs. Russell’s piano was restored in 1995, given to First Church in 2017, and placed in the Jennings Room to complement Violet Oakley’s Great Women of the Bible murals. the first presbyterian church in germantown philadelphia Evelyn Santiago, soprano Margaret Mezzacappa, mezzo soprano Ted W. Barr, piano & Geraldine Rice, viola Sunday Afternoon at 4:00 p.m. October 1, 2017 J Three Robert Browning Songs, op. 44 Amy Beach Ah, Love, but a Day (1867–1944) I Send My Heart Up to Thee! The Year’s at the Spring Ms. Santiago Zwei Gesänge, op. 91 Johannes Brahms Gestillte Sehnsucht (1833–1897) Geistliches Wiegenlied Ms. Mezzacappa & Ms. Rice Two Opera Arias Giacomo Puccini “Donde lieta usci” from La Boheme (1858–1924) “Vissi d’arte” from Tosca Ms. -

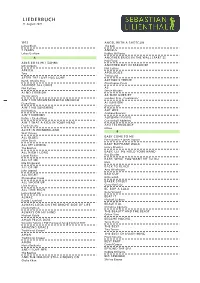

Sebastian Lilienthal

LIEDERBUCH 11. August 2021 1973 ANGEL WITH A SHOTGUN James Blunt The Cab 7 YEARS ANGELS Lukas Graham Robbie Williams A ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL [PART 2] Pink Floyd ABER BITTE MIT SAHNE Udo Jürgens ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE Phil Collins AFRICA Toto APOLOGIZE Timbaland AFTER THE LOVE HAS GONE Earth, Wind & Fire ARTHUR’S THEME Christopher Cross AGAINST ALL ODDS Phil Collins AS Stevie Wonder AI NO CORRIDA Quincy Jones AS TIME GOES BY aus dem Film „Casablanca“ AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH Diana Ross ATTENTION Charlie Puth AIN’T NO SUNSHINE Bill Withers AUF UNS Andreas Bourani AIN’T NOBODY Rufus + Chaka Khan AUTUMN LEAVES Cannonball Adderley AIN’T THAT A KICK IN YOUR HEAD Frank Sinatra AYO TECHNOLOGY Milow ALICE IN WONDERLAND B Walt Disney ALL BLUES BABY COME TO ME Miles Davis Patti Austin + James Ingram ALL MY LOVING BABY ELEPHANT WALK The Beatles Henry Mancini ALL NIGHT LONG BABY, LET ME HOLD YOUR HAND Lionel Richie Ray Charles ALL OF ME BABY, WHAT YOU WANT ME TO DO Ella Fitzgerald Elvis ALL OF ME BACK TO BLACK John Legend Amy Winehouse ALL RIGHT BAD GUY Christopher Cross Billie Eilish ALL SHOOK UP BAKER STREET Elvis Presley Gerry Rafferty ALL TIME HIGH BE-BOP-A-LULA James Bond 007 Gene Vincent ALMAZ BEAT IT Randy Crawford Michael Jackson ALWAYS LOOK ON THE BRIGHT SIDE OF LIFE BEAUTIFUL Monty Python Christina Aguilera ALWAYS ON MY MIND THE BEAUTY AND THE BEAST Michael Bublé Celine Dion AMAR PELOS DOIS BESAME MUCHO Salvador Sobral / ESC European Song Contest 2017 Tania Maria AMAZING GRACE THE BEST Traditional Gospel Tina Turner AMEN THE BEST -

PG-13 Song List 2 Pages

Ramapo Runway “It’s A Wrap” Movie Song Guide MOVIE SONG ARTIST 21 Jump Street Party Rock Anthem LMFAO 8 Mile Lose Yourself Eminem Beverly Hills Cop Axel F Harold Faltermeyer Garden State Don’t Panic (slow) Coldplay Garden State New Slang (slow) The Shins Slumdog Millionaire Jai Ho AR Rahman Almost Famous Reelin’ in the Years Steeley Dan Trainspotting Perfect Day (slow) Lou Reed The Hangover Who Let the Dogs Out Baha Men The Hangover Yeah Usher The Hangover Right Round Flo Rida Goodfellas Layla Eric Clapton Space Jam I Believe I Can Fly (slow) R. Kelly American Reunion Wannabe Spice Girls American Reunion Tub Thumping Chumbawumba American Reunion Sexy and I Know It LMFAO Toy Story You Got a Friend In Me (slow) Randy Newman James Bond (any) James Bond Theme (slow) Monty Norman Shaft Theme from Shaft Isaac Hayes Pink Panther Theme from Pink Panther Henry Mancini Wayne’s World Theme from Wayne’s World Wayne and Garth La Bamba La Bamba Richie Valens Grease You’re the One That I want Travolta/Newton-John Grease Summer Nights Cast Grease We Go Together Cast Men In Black Big Willie Style Will Smith Men In Black 3 Back in Time Pitbull Jackass 3-D Boom Boom Pow Black Eyed Peas The Help Sherry Frankie Valli & the 4 Seasons Pulp Fiction Jungle Boogie Kool and the Gang Blues Brothers Twist It/Shake your tail The Blues Brothers Blues Brothers Soul Man The Blues Brothers Blues Brothers Everybody Needs Somebody The Blues Brothers Ferris Bueller’s Day Off Twist and Shout Beatles Iron Man Back in Black AC/DC Shrek All-Star Smash Mouth Shrek 2 Accidentally in Love Counting Crows Shrek 2 Funkytown Lipps, Inc. -

Jnaezeszletter 93023 April 1988 " Vol

P.O. Box 240 Ojal, Calif. jnaezeszletter 93023 April 1988 " Vol. 7 No.4 jazz albums. I was startled by the clarity of the sound. John Galsworthy and the CD I hope you are familiar with that stereo record of the Duke John Galsworthy wrote a short story titled Quality, about a Ellington band in 1934, issued on a label called Everybody’s. bootmaker in the time when the standardized manufacture of Two microphones were set up in front of the orchestra and two footwear was beginning. The bootmaker laments the loss of separate disc recordings of the band were made. A few years quality he insists is inherent in mass production, and is ruined ago, two recording engineers who were ardent collectors in the end byhis refusal (or inability, which amounts to the same discovered serendipitously that they had different recordings of thing) to accommodate himselfto the changingworld. The high the same session. Excitedlythey hypothesized that ifthey could school teacher who forced this storyon me seemed to be on the synchronize the two and derive a tape from them, they would side of the boot-maker, though I thought in my naivete that have a stereo recording ofEllington made a quarter ofa century making inexpensive shoes available to the masses might just be before commercial stereo came to the marketplace. They did, a Good Thing. and the album is a remarkable document of the band at that Two or three years after I read that story, I encountered a time. small record-shop owner in Montreal who railed against the There is a recording that I have heard about but not heard new-fangled 33 rpm LP developed by CBS. -

Big Daddy's Ultimate Playlist!

BIG DADDY’S ULTIMATE PLAYLIST! It's simple. I scroll through my iPod and when I come upon an artist that I have at least 15 songs by, I then pick one AND ONLY ONE song to make THE ULTIMATE PLAYLIST. (The number next to the artist is how many songs I have by that artist on my I-pod) A AC/DC... 17... YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG ARETHA FRANKLIN... 27... RESPECT Came close to selecting the live DR. FEELGOOD off ARETHA IN PARIS, but there is no denying the power and majesty of RESPECT. After a gazillion listens, it STILL rocks. AL GREEN... 16... LET’S STAY TOGETHER ALANIS MORISSETTE... 15... THE COUCH What can I say? I loved her first two CD's which is how she ended up with EXACTLY 15 songs ARTIE SHAW... 21... DANCIN’ IN THE DARK B THE BAND... 18... RAG, MAMA RAG B-52S... 15... PLANET CLAIRE BARRY WHITE... 16... YOU’RE MY FIRST, MY LAST, MY EVERYTHING BEACH BOYS... 116... GIRLS ON THE BEACH I know what you're thinking, this should be GOD ONLY KNOWS or a million others, but this one just floors me with it's staggering harmonies and innocence and it's also one of the first Beach Boy tunes I ever heard . BEATLES... 198... YOU CAN’T DO THAT No, I'm not kidding. BEASTIE BOYS... 25... SURE SHOT BEN FOLDS... 32... SONG FOR THE DUMPED BENNY GOODMAN... 22... WHAT’S NEW BOB DYLAN... 115... LIKE A ROLLING STONE I could have easily went with Adam's pick or many others, but ROLLING STONE gives you six minutes worth of Bob.