APPENDIX United States V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Establishes Task Force on COVID-19 Infections at Nursing Homes

https://www.redlandscommunitynews.com/news/public_safety/county-establishes-task-force-on-covid-19- infections-at-nursing-homes/article_824d5044-7873-11ea-a1d4-c37d6e4dbb4c.html BREAKING County establishes task force on COVID-19 infections at nursing homes Alejandro Cano, reporter, Redlands Community News Apr 6, 2020 In response to the recent outbreaks at a Yucaipa and Colton nursing facilities, the San Bernardino County Department of Public Health established on Monday, April 6, a multiagency Nursing Facilities Task Force to avoid the spread of COVID-19 among the elderly population. Acting County Health Ofcer Erin Gusfatson also ordered nursing facilities to take multiple steps to protect the elderly population and health-compromised clients. The order requires nursing home staff to wear protective gear and to monitor staff members’ temperatures to prevent the spread. The order also forbids employees from entering facilities if they have symptoms of any contagious disease, Gustafson said. “Without appropriate precautions and procedures, nursing homes can create a tragically ideal environment for the spread of viruses among those who are most susceptible to symptoms and complications,” Gustafson said. According to the Department of Public Health, San Bernardino County has 171 state-licensed nursing facilities caring for at least 6,600 of the county’s most at-risk residents. On Saturday, April 4, California Gov. Gavin Newsom identied San Bernardino County as one of four nursing home “hotspots” in the state. “The county is dedicating every resource we can to ghting the spread of COVID-19,” said Board of Supervisors Chairman Curt Hagman. “This task force will focus on supporting our senior living facilities in their efforts to preserve the safety of their residents.” The idea to create the task force began after the outbreak at Cedar Mountain Post-Acute Rehabilitation in Yucaipa where 75 residents and staff tested positive for COVID-19, a disease that has also killed ve residents at the same facility. -

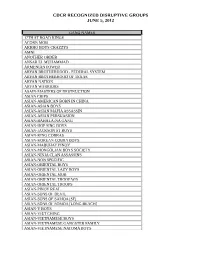

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

Certified for Partial Publication*

Filed 3/13/15 CERTIFIED FOR PARTIAL PUBLICATION* COURT OF APPEAL, FOURTH APPELLATE DISTRICT DIVISION ONE STATE OF CALIFORNIA THE PEOPLE, D066979 Plaintiff and Respondent, v. (Super. Ct. No. FVI1002669) ROBERT FRANK VELASCO, Defendant and Appellant. APPEAL from a judgment of the Superior Court of San Bernardino County, Eric M. Nakata, Judge. Affirmed in part; reversed in part; remanded with directions. Brett Harding Duxbury, under appointment by the Court of Appeal, for Defendant and Appellant. Kamala D. Harris, Attorney General, Julie L. Garland, Assistant Attorney General, Eric A. Swenson and Lynne G. McGinnis, Deputy Attorneys General, for Plaintiff and Respondent. * Pursuant to California Rules of Court, rule 8.1110, this opinion is certified for publication with the exception of parts II and III. The jury convicted Robert Frank Velasco of attempted first degree robbery (Pen. Code,1 §§ 664/211; count 1); assault with a firearm (§ 245, subd. (a)(2); count 4); possession of a firearm by a felon (§ 1201, subd. (a)(1); count 5); and street terrorism (§ 186.22, subd. (a); count 6). The jury also found, as to counts 1 and 4, that Velasco personally used a firearm within the meaning of section 12022.5, subdivision (a). The jury found Velasco not guilty of first degree burglary (§ 459; count 2). It also returned a not true finding on the robbery in concert within the meaning of section 213, subdivision (a) in connection with count 1. In addition, the jury was unable to reach verdicts that counts 1, 4, and 5 were committed for the benefit of, at the direction of, or in association with, a criminal street gang, within the meaning of section 186.22, subdivision (b)(1). -

United States Attorney's Office Central District Of

United States Attorney’s Office Central District of California ANNUAL REPORT January 2015 – December 2015 Eileen M. Decker United States Attorney TABLE OF CONTENTS FROM THE DESK OF THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY.…………………………….……….3 CASES……………………………………………………………………………………………………...4 APPEALS…………………………………………………………………………………………..4 CIVIL RIGHTS……..……………………………………………………………………………...6 COMMUNITY SAFETY…………………………………………………………………………..8 CRIMES AGAINST CHILDREN………………………………………………………………...10 CRIMES AGAINST THE GOVERNMENT…………………………………………………….12 Immigration Fraud………………………………………………………………………....14 Export Controls…………………………………………………………………………....15 CYBER………………………………………………………………………………………….....16 ENVIRONMENTAL……………………………………………………………………………..18 FRAUD…………………………………………………………………………………………....20 Bank Fraud………………………………………………………………………………...20 Embezzlement …………………………………………………………………………….21 Healthcare Fraud……………………………………………………………………….......22 Identity Theft………………………………………………………………………….…...25 Securities Fraud……………………………………………………………………….…....26 Investment Fraud…………………………………………………………………….…….27 Real Estate Fraud…………………………………………………………………….…......30 Mortgage Adjustment Fraud………………………………………………………….…......31 GENERAL CIVIL…………………………………………………………………………….…...33 HUMAN TRAFFICKING………………………………………………………………………....38 PRESCRIPTION DRUG ABUSE…………………………………………………………………39 PUBLIC CORRUPTION…………………………………………………………………………..41 Embezzlement……………………………………………………………………………...42 TAX FRAUD……………………………………………………………………………………....43 1 TERRORISM……………………………………………………………………………………...45 VIOLENT CRIME………………………………………………………………………………..47 -

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 13-50088 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 2:10-cr-00567-AHM-4 MICHAEL ANTHONY TORRES, Defendant-Appellant. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 13-50095 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 2:10-cr-00567-AHM-2 CESAR MUNOZ GONZALEZ, AKA Blanco, AKA Cesar Gonzales, AKA Ricardo Martines, AKA Ricardo O. Martinez, AKA Ricardo Martinez-Osorio, AKA Osorio Ricardo, Defendant-Appellant. 2 UNITED STATES V. TORRES UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 13-50102 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 2:10-cr-00567-AHM-1 RAFAEL MUNOZ GONZALEZ, AKA “C”, AKA Cisco, AKA Homeboy, AKA Big Homie, Defendant-Appellant. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 13-50107 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 2:10-cr-00567-AHM-3 ABRAHAM ALDANA, AKA Listo, OPINION Defendant-Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Alvin Howard Matz, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted March 8, 2016 Submission Vacated September 27, 2016 Resubmitted September 6, 2017 Pasadena, California Filed September 6, 2017 UNITED STATES V. TORRES 3 Before: Richard R. Clifton and Sandra S. Ikuta, Circuit Judges and Frederic Block,* Senior District Judge. Opinion by Judge Ikuta; Concurrence by Judge Clifton (setting forth the majority opinion as to Appellants’ challenge to Jury Instruction 50) SUMMARY** Criminal Law The panel affirmed four defendants’ convictions and sentences for racketeering, drug trafficking conspiracy, and related offenses involving the Puente-13 street gang. The panel held that the district court’s jury instruction for determining drug quantities under 21 U.S.C. -

The Azusa 13 Indictment

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 February 2011 Grand Jury 11 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) CR No. 11-_____________ ) 12 Plaintiff, ) I N D I C T M E N T ) 13 v. ) [18 U.S.C. § 1962(d): ) Racketeer Influenced and 14 SANTIAGO RIOS, ) Corrupt Organizations aka “Chico,” ) Conspiracy; 18 U.S.C. § 241: 15 GEORGE SALAZAR, ) Conspiracy Against Rights; aka “Jorge Salazar,” ) 21 U.S.C. § 846: Conspiracy to 16 aka “Danger,” ) Distribute and to Possess with ANTHONY MORENO, ) Intent to Distribute Heroin, 17 aka “Flaco,” ) Methamphetamine, and Cocaine; LOUIS MARTINEZ, ) 21 U.S.C. §§ 841(a)(1), 18 aka “Luista,” ) 841(b)(1) (B), (C), (E): JOSUE ALFARO, ) Possession with Intent to 19 aka “Negro,” ) Distribute and Distribution LOUIE RIOS, ) of Heroin, Methamphetamine, 20 aka “Lil’ Chico,” ) and Hydrocodone; 18 U.S.C. DAVID PADILLA, JR., ) § 922(g)(1): Felon in 21 aka “Lil’ Dreamer,” ) Possession of a Firearm; BERNARD GOMEZ, JR., ) 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A)(i): 22 aka “Lil’ Bernie,” ) Use and Carry, and Possession, RAUL AGUIRRE, ) of a Firearm During and in 23 aka “Solo,” ) Relation to, and in THOMAS URIOSTE, ) Furtherance of, a Crime of 24 aka “Tommy-Gunz,” ) Violence or Drug Trafficking EDWARD RIVERA, ) Crime; 21 U.S.C. § 843: Use of 25 aka “Bleu,” ) a Communication Facility to ROBERT VALLES, ) Commit a Drug Trafficking 26 aka “Zombie,” ) Crime] RAYMOND PELAYO, ) 27 aka “Crow,” ) aka “Curly,” ) 28 ) 1 PAUL LOPEZ, ) 2 aka “Mugsy,” ) JAVIER LEON, ) 3 aka “Silent,” ) DANIEL JUAREZ, ) 4 aka “Rusher,” ) -

News Release

News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE U.S. Attorney‟s Office: (213) 894-6947 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2010 ICE Public Affairs: (949) 337-9594 Los Angeles Police Dept: (213) 486-5910 ATF: (818) 265-2507 Feds indict 61 in multi-agency drug probe focusing on Los Angeles-area gangs Operation “Red Rein” targeted gangs' key meth and cocaine suppliers LOS ANGELES – More than 800 federal and local law enforcement officers fanned out across the Southland Thursday morning in a massive takedown capping a three-year, multi-agency investigation that targeted major methamphetamine and cocaine suppliers to some of the most violent street gangs based in Los Angeles, Long Beach and La Puente. Early this afternoon, 40 of the suspects facing federal charges in the case were in custody, with 35 being arrested this morning and five of the defendants already in jail. A total of 21 defendants named in federal indictments are still being sought. Additionally, one other individual was detained on a state parole violation. Besides the arrests, the Los Angeles City Attorney‟s Office filed a civil “abatement” lawsuit Thursday to shut down drug trafficking activities at a notorious hotel used as a hangout by a Harbor Area gang. Thursday‟s arrests come after a federal grand jury returned six indictments that name a total of 61 defendants, many of them documented gang members, who allegedly trafficked in large quantities of cocaine and meth that various gangs resold. The charges in the indictments include conspiracy to distribute methamphetamine and cocaine as well as firearms violations. The federal defendants were expected to be arraigned in United States District Court Thursday afternoon. -

Septuagenarian Declares Full Speed Ahead for 2017

WWW.BEVERLYPRESS.COM INSIDE Measure S becomes war Sunny with of words p. 3 temps in the Lessons from the mid 70s bullpen p. 6 Volume 26 No. 52 Serving the West Hollywood, Hancock Park, Beverly Hills and Wilshire Communities December 29, 2016 Future includes n preserving past Septuagenarian2016 marked 70 years declares full speed ahead for 2017 for Park Labrea News inn Beverly Hills Mills Act program gives To paraphrase Vin Scully, in a tax breaks for owners of year that has been so unlikely, the historic structures unimaginable has happened. Starting with the election of Donald Trump, the Park La Brea News and Beverly Press has never If you own a Beverly Hills prop- reported on a year quite like 2016. erty that deserves to be included on The 70th anniversary of the the landmark registry, the city Park La Brea News was chroni- wants to make a deal to help ensure cled in the special edition “Our it’s protected. People Our Places,” a magazine The Beverly Hills City Council published on April 21 highlighting last week agreed to extend the Mills the many contributors, cultural Act Pilot Program, which planning institutions and attractions that staff said is “one of the most impor- define and drive the community. It tant tools in the toolbox” to incen- included interviews with iconic tivize historic preservation. Now, figures like longtime Los Angeles the city is encouraging owners of Dodgers announcer Vin Scully, qualifying historic structures – resi- billionaire philanthropist Eli dential or commercial – to apply for Broad and Father Greg Boyle, tax relief in exchange for mainte- founder of Homeboy Industries. -

Surenos Report

A SPECIAL REPORT FROM THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN INFORMATION NETWORK LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE Rocky Mountain Information Network (RMIN) is one of six regional projects in the United States that comprise the Regional Information Sharing Systems (RISS). Each project links law enforcement agencies from neighboring states into a regional network that interacts with law enforcement member agencies nationwide. Funded by Congress through the Bureau of Justice Assistance, RISS provides secure commu- nications, information sharing resources and investigative support to combat multi-jurisdictional crime. RMIN is headquartered in Phoenix and serves more than 1,040 law enforcement member agencies in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming and the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan in Canada. Rocky Mountain Information Network P.O. Box 41370 Phoenix, AZ 85080-1370 623-587-8201 800-821-0640 John E. Vinson, Executive Director Jeff Crane, Editor Kate von Seeburg, Publications Support Specialist Surenos 2008 “One rule, one law, one order.” Surenos 2008 is a special report produced by the Publications Department of Rocky Mountain Information Network. The project was supported by Grant No. 2008-RS-CX-K004 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a com- ponent of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime. Points of view or opinions in this docu- ment are those of the author and do not represent the official position or policies of the United States Department of Justice and may not represent the opinion of the RMIN Executive Policy Board of Directors. -

Systemic Racial Bias and RICO's Application to Criminal Street and Prison Gangs

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 17 2012 Systemic Racial Bias and RICO's Application to Criminal Street and Prison Gangs Jordan Blair Woods University of Cambridge Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Jordan B. Woods, Systemic Racial Bias and RICO's Application to Criminal Street and Prison Gangs, 17 MICH. J. RACE & L. 303 (2012). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol17/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYSTEMIC RACIAL BIAS AND RICO'S APPLICATION TO CRIMINAL STREET AND PRISON GANGS Jordan Blair Woods* This Article presents an empirical study of race and the application of the frderal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) to criminal street and prison gangs. A strong majority (approximately 86%) of the prosecutions in the study involved gangs that were affiliated with one or more racial minority groups. All but one of the prosecuted White-affiliated gangs fell into three categories: international organized crime groups, outlaw motorcycle gangs, and White supremacist prison gangs. Some scholars and practitioners would explain these findings by contending that most criminal street gangs are comprised of racial minorities. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Case: 13-50102, 09/06/2017, ID: 10569987, DktEntry: 119-1, Page 1 of 40 FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 13-50088 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 2:10-cr-00567-AHM-4 MICHAEL ANTHONY TORRES, Defendant-Appellant. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 13-50095 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 2:10-cr-00567-AHM-2 CESAR MUNOZ GONZALEZ, AKA Blanco, AKA Cesar Gonzales, AKA Ricardo Martines, AKA Ricardo O. Martinez, AKA Ricardo Martinez-Osorio, AKA Osorio Ricardo, Defendant-Appellant. Case: 13-50102, 09/06/2017, ID: 10569987, DktEntry: 119-1, Page 2 of 40 2 UNITED STATES V. TORRES UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 13-50102 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 2:10-cr-00567-AHM-1 RAFAEL MUNOZ GONZALEZ, AKA “C”, AKA Cisco, AKA Homeboy, AKA Big Homie, Defendant-Appellant. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, No. 13-50107 Plaintiff-Appellee, D.C. No. v. 2:10-cr-00567-AHM-3 ABRAHAM ALDANA, AKA Listo, OPINION Defendant-Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Alvin Howard Matz, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted March 8, 2016 Submission Vacated September 27, 2016 Resubmitted September 6, 2017 Pasadena, California Filed September 6, 2017 Case: 13-50102, 09/06/2017, ID: 10569987, DktEntry: 119-1, Page 3 of 40 UNITED STATES V. TORRES 3 Before: Richard R. Clifton and Sandra S. Ikuta, Circuit Judges and Frederic Block,* Senior District Judge. Opinion by Judge Ikuta; Concurrence by Judge Clifton (setting forth the majority opinion as to Appellants’ challenge to Jury Instruction 50) SUMMARY** Criminal Law The panel affirmed four defendants’ convictions and sentences for racketeering, drug trafficking conspiracy, and related offenses involving the Puente-13 street gang. -

The 2011 National Gang Threat Assessment (Ngta)

NATIONAL GANG INTELLIGENCE CENTER 2011 NATIONAL GANG THREAT ASSESSMENT Emerging Trends SPECIAL THANKS TO THE NATIONAL DRUG INTELLIGENCE CENTER FOR THEIR CONTRIBUTIONS AND SUPPORT. 2011 National Gang Threat Assessment The gang estimates presented in the 2011 National Gang Threat Assessment (NGTA) represents the collection of data provided by the National Drug intelligence Center (NDiC) – through the National Drug Threat Survey, Bureau of Prisons, State Correctional Facilities, and National Gang Intelligence Center (NGIC) law enforcement partners. An overview of how these numbers were collected is described within the Scope and Methodology Section of the NGTA. The estimates were provided on a voluntary basis and may include estimates of gang members as well as gang associates. Likewise, these estimates may not capture gang membership in jurisdictions that may have underreported or who declined to report. Based on these estimates, geospatial maps were prepared to visually display the reporting jurisdictions. The data used to calculate street gangs and Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs estimates nationwide in the report are derived primarily from NDiC’s National Drug Threat Survey. These estimates do not affect the qualitative findings of the 2011 NGtA and were used primarily to create the map’s highlighting gang activity nationally. After further review of these estimates, the maps originally provided in 2011 NGTA were revised to show state-level representation of gang activity per capita and by law enforce- ment officers. this maintains consistency with the 2009 NGtA report’s maps on gang activity. During the years the NGTa is published, many entities—news media, tourism agencies, and other groups with an interest in crime in our nation; use reported figures to compile rankings of cities and counties.