Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bisexuality in William Shakespeare's Crossdressing Plays

“Betrothed Both to a Maid and Man”: Bisexuality in William Shakespeare’s Crossdressing Plays The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37945131 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “Betrothed Both to a Maid and Man”: Bisexuality in William Shakespeare’s Crossdressing Plays Danielle Warchol A Thesis in the Field of English for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2018 Copyright 2018 Danielle Warchol Abstract This thesis examines the existence of bisexuality in William Shakespeare’s three major crossdressing plays: The Merchant of Venice, As You Like It, and Twelfth Night. The past few decades have seen several homoerotic interpretations of Shakespeare's crossdressing plays, but many of these readings argue that same-sex desire is transitional and that because the plays end in opposite-sex marriage, same-sex desire can never be consummated. While a case can be made for these arguments, readings that rely on the heterosexual-homosexual binary overlook the possibility of bisexual identities and desire within the plays. Historical accounts illustrate that same-sex relationships and bisexual identities did exist during the Elizabethan era. However, I will be examining bisexuality from a modern perspective and, as such, will not discuss the existence, or lack thereof, of bisexual terminology within early modern culture or as it relates to Shakespeare’s own sexual identity. -

Twelfth Night," and "Othello"

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2008 The male homoerotics of Shakespearean drama: A study of "The Merchant of Venice," "Twelfth Night," and "Othello" Anthony Guy Patricia University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Patricia, Anthony Guy, "The male homoerotics of Shakespearean drama: A study of "The Merchant of Venice," "Twelfth Night," and "Othello"" (2008). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2314. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/mxfv-82oj This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MALE HOMOEROTICS OF SHAKESPEAREAN DRAMA: A STUDY OF THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, TWELFTH NIGHT, AND OTHELLO by Anthony Guy Patricia Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in English Department of English College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2008 UMI Number: 1456363 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Queering the Shakespeare Film Ii Queering the Shakespeare Film Gender Trouble, Gay Spectatorship and Male Homoeroticism

Queering the Shakespeare Film ii Queering the Shakespeare Film Gender Trouble, Gay Spectatorship and Male Homoeroticism Anthony Guy Patricia Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as Arden Shakespeare 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY, THE ARDEN SHAKESPEARE and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2017 © Anthony Guy Patricia, 2017 Anthony Guy Patricia has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-1-4742-3703-1 ePDF: 978-1-4742-3705-5 ePub: 978-1-4742-3704-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Cover image: Imogen Stubbs as Viola and Toby Stephens as Orsino, -

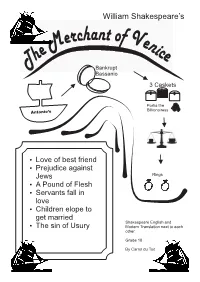

William Shakespeare's

William Shakespeare’s Bankrupt Bassanio 3 Caskets Portia the Antonio’s Billionairess Love of best friend Prejudice against Jews Rings A Pound of Flesh Servants fall in love Children elope to get married Shakespeare English and The sin of Usury Modern Translation next to each other. Grade 10 By Carrol du Toit William Shakespeare William Shakespeare was born in 1564 and died in 1616. He is recognized in the world as the greatest dramatist. Some of the 35 plays written by William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet Macbeth Othello As you like it The Merchant of Venice Twelfth Night King Lear Hamlet The Elizabethan World Queen Elizabeth was the Queen of England I from 1558-1603. Elizabethans had a very strong sense of social order: they believed that their queen was God's representative on Earth, and that God had created and blessed the ranks of society, from the monarch down through the nobility, gentry, merchants, and labourers. The English Parliament even passed laws on the clothes people could wear: it would have been unthinkable for, for example, a merchant to imitate wealthier individuals, and against the social order. Elizabethans considered families to be a model for the rest of their society: ordered, standardized, and with a strict sense of hierarchy. The accepted norms for children's behaviour, for example, were based on passages in the Bible. Although Elizabeth's subjects were becoming more aware of comfort at home, life was still very hard for most, by modern standards. Average life expectancy was nearly 42 years of age, but the wealthy generally lived longer. -

The Merchant of Venice, Secures a Loan from Shylock for His Friend Bassanio, Who Seeks to Court Portia

Folger Shakespeare Library https://shakespeare.folger.edu/ Contents From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library Front Textual Introduction Matter Synopsis Characters in the Play Scene 1 ACT 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 4 ACT 2 Scene 5 Scene 6 Scene 7 Scene 8 Scene 9 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 3 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 1 ACT 4 Scene 2 ACT 5 Scene 1 From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library It is hard to imagine a world without Shakespeare. Since their composition four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays and poems have traveled the globe, inviting those who see and read his works to make them their own. Readers of the New Folger Editions are part of this ongoing process of “taking up Shakespeare,” finding our own thoughts and feelings in language that strikes us as old or unusual and, for that very reason, new. We still struggle to keep up with a writer who could think a mile a minute, whose words paint pictures that shift like clouds. These expertly edited texts are presented to the public as a resource for study, artistic adaptation, and enjoyment. By making the classic texts of the New Folger Editions available in electronic form as The Folger Shakespeare (formerly Folger Digital Texts), we place a trusted resource in the hands of anyone who wants them. The New Folger Editions of Shakespeare’s plays, which are the basis for the texts realized here in digital form, are special because of their origin. -

3L Reading Packet Week 9 Keep This

3L Reading Packet Week 9 Keep this packet. You WILL need some of the readings next week – especially the Merchant of Venice pages! Week 9 3L READING - Page 1 MATH INSTRUCTIONS Week 9 3L READING - Page 3 Ms. Medcalf’s Math Scholars- Here are things to keep in mind: 1. The checklist is a guideline to make sure you complete everything you are asked to complete within the week. We encourage you to do as much as you can on any assignment. 2. Please complete ALL PROBLEMS for each problem set. You are required to complete all 30 problems in each problem set for every lesson going forward. 3. Please put your first and last name AND your math teacher’s name (Ms. Medcalf) at the top of EVERY math page! This will help the staff who sort the work to ensure that I get all the work from my scholars. For Week 9 of distance learning (May 29th – June 4th), Ms. Medcalf’s classes should complete all the problems in the sets for: 3L Saxon 8/7: Lessons 73, 74, 75 3L Algebra ½: Lessons 103, 104, 105 For additional resources to help you through the lessons, take a look at our website www.parnassusteachers.com; the password is: Pegasus. Click on “School of Logic” to find resources organized by subject. Feel free to email me at [email protected], or call/text me at 612- 465-9631 with any questions you have about anything school related. Nothing to it but to do it. You’re almost there! Ms. Medcalf Week 9 3L READING - Page 4 ENGLISH INSTRUCTIONS Week 9 3L READING - Page 5 3L English- Ms. -

The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare

The Merchant of Venice By William Shakespeare Act 3, Scene 2 The Merchant of Venice: Act 3, Scene 2 by William Shakespeare SCENE. Belmont. A room in PORTIA's house. (Enter BASSANIO, PORTIA, GRATIANO, NERISSA, and Attendants.) PORTIA. I pray you tarry; pause a day or two Before you hazard; for, in choosing wrong, I lose your company; therefore forbear a while. There's something tells me, but it is not love, I would not lose you; and you know yourself Hate counsels not in such a quality. But lest you should not understand me well,— And yet a maiden hath no tongue but thought,— I would detain you here some month or two Before you venture for me. I could teach you How to choose right, but then I am forsworn; So will I never be; so may you miss me; But if you do, you'll make me wish a sin, That I had been forsworn. Beshrew your eyes, They have o'erlook'd me and divided me: One half of me is yours, the other half yours, Mine own, I would say; but if mine, then yours, And so all yours. O! these naughty times Puts bars between the owners and their rights; And so, though yours, not yours. Prove it so, Let fortune go to hell for it, not I. I speak too long, but 'tis to peise the time, To eke it, and to draw it out in length, To stay you from election. BASSANIO. Let me choose; For as I am, I live upon the rack. -

Shakespeare and the Uses of Comedy

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, British Isles English Language and Literature 2014 Shakespeare and the Uses of Comedy J. A. Bryant Jr. University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bryant, J. A. Jr., "Shakespeare and the Uses of Comedy" (2014). Literature in English, British Isles. 97. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_british_isles/97 Shakespeare & the Uses of Comedy This page intentionally left blank J.A. Bryant, Jr. Shakespeare & the Uses of Comedy THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1986 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0024 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bryant, J. A. (Joseph Allen), 1919- Shakespeare and the uses of comedy. Bibliography; p. Includes index. l. Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616-Comedies. I. Title. PR298l.B75 1987 822.3'3 86-7770 ISBN 978-0-8131-5632-3 For Allen, Virginia, and Garnett This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments IX 1. -

Screening the Male Homoerotics of Shakespearean Romantic Comedy

Guy Patricia, Anthony. "Screening the male homoerotics of Shakespearean romantic comedy on film in Michael Radford’s The Merchant of Venice and Trevor Nunn’s Twelfth Night." Queering the Shakespeare Film: Gender Trouble, Gay Spectatorship and Male Homoeroticism. London: Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare, 2017. 135–180. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474237062.ch-004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 18:58 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Guy Patricia 2017. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 Screening the male homoerotics of Shakespearean romantic comedy on film in Michael Radford’s The Merchant of Venice and Trevor Nunn’s Twelfth Night I Two groundbreaking articles from 1992 continue to draw attention to the subject of male homoeroticism in Shakespearean romantic comedy, specifically in plays like The Merchant of Venice and Twelfth Night.1 In these pieces a fair amount of critical attention is directed to what Joseph Pequigney cleverly referred to as ‘the two Antonios’, the pair of characters that are linked to one another not only by name, but because both exhibit pronounced homoerotic desire for other male characters in the plays they appear; those 9781474237031_txt_print.indd 135 29/07/2016 14:51 136 QUEERING THE SHAKESPEARE FILM being Bassanio in Merchant and Sebastian in Twelfth Night. Systematically comparing the relationships of these characters, Pequigney argues that the relationship between Antonio and Bassanio in Merchant is never anything but platonic and that, conversely, the relationship between Antonio and Sebastian in Twelfth Night is romantic and, more significantly, is also requited in some fashion in the space just off the margins of the playtext. -

Screening the Male Homoerotics of Shakespearean Drama in Anglophone Cinema, 1936-2011

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2014 Through the Eyes of the Present: Screening the Male Homoerotics of Shakespearean Drama in Anglophone Cinema, 1936-2011 Anthony Guy Patricia University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Repository Citation Patricia, Anthony Guy, "Through the Eyes of the Present: Screening the Male Homoerotics of Shakespearean Drama in Anglophone Cinema, 1936-2011" (2014). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2131. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/5836150 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THROUGH THE EYES OF THE PRESENT: SCREENING THE MALE HOMOEROTICS OF SHAKESPEAREAN DRAMA IN ANGLOPHONE CINEMA, 1936 -

May I Quote You on That?: a Guide to Grammar and Usage

May I Quote You on That? May I Quote You on That? A Guide to Grammar and Usage STEPHEN‘ SPECTOR 1’ 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form, and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available ISBN 978-0-19-021528-6 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Mary, who makes everything possible and everything better Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction xi About the Companion Website xix 1. -

Valuable & Able to Value: a Shakespearean Method By

Valuable & Able to Value: A Shakespearean method ___ PRATIBHA RAI In this article, I analyse Shakespeare’s versatile play on the theme of ‘value’ through his employment of metallurgical coinage as human metaphor. My discussion revolves around artefacts from the British Museum: a Venetian gold ducat (1523–38) and a wooden box containing brass coin-weights and hand balance (1600–54), as well as a foray into Shakespeare’s plays. Through the lexicon of finance, Shakespeare unravels the complexity of the human condition as money is enmeshed with human instincts and emotions. That is to say, the metal of coinage reveals human mettle. believe that the theme of value is among the chief concerns in the I Shakespearean corpus. One of the repeated images that the playwright employed to communicate this theme was the value of coins weighed alongside the value of individuals. Shakespeare’s plays allude to the ingrained Early Modern habit of testing the authenticity of money using coin-weights and balances. However, so often he employs the metallurgical as metaphorical about testing character, illuminating a milieu concerned with truth and legitimacy in a pluralistic sense. Shakespeare deftly utilises monetary parlance with its assignable values to give concrete shape to intangible human qualities. This Venetian ducat, now in the British Museum, is made from almost completely pure gold and was minted between 1523-1538. The origin of the name ‘ducat’ derives from the word for ‘duke’ in Latin. The simulacrum visibly evidences its etymological origin as this ducat bears both the name and image of Andrea Gritti, the Doge or Duke of Venice, who issued it.