MIASURING the SHIFT of L{INNIPTG.S RETA]L FUNCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warhol in Winnipeg

k t '^ Red River C*Ilege projectorstaff EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nisha Tuli [email protected] GUERRILLA GARDENING PG.3 REBEL WITH A TROWEL HEALTH SPORTS & LIFESTYLES EDITOR Andrea Danelak LETTER TO THE EDITOR [email protected] PG. 5 WHAT'S WRONG WITH THE PRINCESS STREET CAMPUS? RRC TO ACQUIRE NEW BUILDING? Chris Webb PG.5 UNION BANK UP FOR GRABS [email protected] JOURNALIST SUBMITS CRAP PG.7 NO MENTION OF GOAT BINGO ARTS & CULTURE EDITOR PLIGHT OF THE HOMELESS Sara Atnikov PG.7 [email protected] HARD LIVES ON THE STREETS WARHOL IN WINNIPEG PG.14 EXHIBIT BRINGS FATHER OF POP ART LAYOUT & DESIGN EDITOR Doug McArthur HERE'S TO BEING UNDRUNK [email protected] PG.22 CAMPAIGN TAKES INITIATIVE Cover Design LAYOUT & DESIGN EDITOR Matt Stevens Chelsea Gowryluk [email protected] Contributing Writers Karen Kornelsen Randi-Leigh Michaniuk Dawn Hinchliffe ADVERTISING CONTACT Sula Johnson Guy Lussier [email protected] Wade Argo Shannah-Lee Vidal Julijana Capone Tania Kohut Jennifer Ryan Tamara Forianski Tim Phelan Jolene Bergen Matt Meisner Red Rkerollege Leigh Enns projector Melody Rogan Sam Karney c/o Red River College Students' Association Darren Cameron P110 -160 Princess Street Winnipeg, MB R3B 1K9 Phone: 204.947.0013 Fax: 204.949.9150 Writers, Photographers, and Illustrators: The Projector Wants You! The Projector is continually searching for new content and new points of view. If you've got something to say, an opinion or interesting story from on or off campus, or illustrations or photos, contact one of our editors with your idea. See your name in print! Contact The Projector today. -

Application Record

Court File No. ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF A PLAN OF COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF PAYLESS SHOESOURCE CANADA INC. AND PAYLESS SHOESOURCE CANADA GP INC. (the “Applicants”) APPLICATION RECORD February 19, 2019 Cassels Brock & Blackwell LLP 2100 Scotia Plaza 40 King Street West Toronto, ON M5H 3C2 Ryan Jacobs LSO#: 59510J Tel: 416. 860.6465 Fax: 416. 640.3189 [email protected] Jane Dietrich LSO#: 49302U Tel : 416. 860.5223 Fax : 416. 640.3144 [email protected] Natalie E. Levine LSO#: 64980K Tel : 416. 860.6568 Fax : 416. 640.3207 [email protected] Lawyers for Payless ShoeSource Canada Inc., Payless ShoeSource Canada GP Inc. and Payless ShoeSource Canada LP TO: SERVICE LIST ATTACHED LEGAL*47453748.1 SERVICE LIST TO: Cassels Brock & Blackwell LLP Scotia Plaza 40 King Street West, Suite 2100 Toronto, ON M5H 3C2 Ryan Jacobs Tel: 416.860.6465 Fax: 416.640.3189 [email protected] Jane Dietrich Tel: 416.860.5223 Fax: 416.640.3144 [email protected] Natalie E. Levine Tel: 416.860.6568 Fax: 416.640.3207 [email protected] Monique Sassi Tel: 416.860.6572 Fax: 416.642.7150 [email protected] Lawyers for Payless ShoeSource Canada Inc., Payless ShoeSource Canada GP Inc. and Payless ShoeSource Canada LP, (collectively, the “Payless Canada Entities”) LEGAL*47453748.1 AND TO: Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP One Bryant Park New York, NY 10036-6745 Ira Dizengoff Tel: 212.872.1096 Fax: 212.872.1002 [email protected] Meredith Lahaie Tel: 212.872.8032 Fax: 212.872.1002 [email protected] Kevin Zuzolo Tel: 212.872.7471 Fax: 212.872.1002 [email protected] Julie Thompson Tel: 202.887.4516 Fax: 202.887.4288 [email protected] Lawyers for Payless Holdings LLC and its debtor affiliates AND TO: FTI Consulting Canada Inc. -

Ads Canadian Bank 343 Amex Bank of Canada 303 Bank Of

SECTION I NUMERIC LIST / LISTE NUMÉRIQUE 1 ADS CANADIAN BANK 343 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 034300012 00012-343 20 Queen Street West - Suite 2600, Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 034300092 00092-343 20 Queen Street West - Suite 2600, Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 AMEX BANK OF CANADA 303 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030300012 00012-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300022 00022-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300032 00032-303 101 McNabb Street, 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 BANK OF AMERICA NATIONAL ASSOCIATION 241 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 024101312 01312-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 024156792 56792-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 BANK OF CANADA 177 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 017700000 00000-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 017700006 00006-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 BANK OF CHINA (CANADA) 308 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030800012 00012-308 50 Minthorn BLVD-Suite 600, Markham, ON L3T 7X8 030800022 00022-308 Toronto Downtown -

Ads Canadian Bank 343 Amex Bank of Canada 303 Bank Of

SECTION I NUMERIC LIST / LISTE NUMÉRIQUE 1 ADS CANADIAN BANK 343 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 034300012 00012-343 20 Queen Street West - Suite 2600, Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 034300092 00092-343 20 Queen Street West - Suite 2600, Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 AMEX BANK OF CANADA 303 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030300012 00012-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300022 00022-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300032 00032-303 101 McNabb Street, 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 BANK OF AMERICA NATIONAL ASSOCIATION 241 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 024101312 01312-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 024156792 56792-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 BANK OF CANADA 177 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 017700000 00000-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 017700006 00006-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 BANK OF CHINA (CANADA) 308 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030800012 00012-308 50 Minthorn BLVD-Suite 600, Markham, ON L3T 7X8 030800022 00022-308 Toronto Downtown -

308 Burnaby Branch, 115-4603 Kingsway, Burnaby, BC V5H 4M4 030800121 00121-308 MONTREAL BRANCH, 1000 Sherbrooke St W-Suite 920, Montreal, QC H3A 0A6

SECTION I NUMERIC LIST / LISTE NUMÉRIQUE 1 AMEX BANK OF CANADA 303 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030300012 00012-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300022 00022-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300032 00032-303 101 McNabb Street, 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 BANK OF AMERICA NATIONAL ASSOCIATION 241 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 024101312 01312-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 024156792 56792-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 BANK OF CANADA 177 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 017700000 00000-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 017700006 00006-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 BANK OF CHINA (CANADA) 308 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030800012 00012-308 3265 Highway 7 East - Unit3, Markham, ON L3R 3P9 030800022 00022-308 Toronto Downtown Branch, 396 Dundas Street West, Toronto, ON M5T 1G7 030800030 00030-308 Vancovuer Branch, 1025 Dunsmuir Street, 1025 Dunsmuir Street PO Box 49277, Vancouver, BC V7X 1L3 030800050 00050-308 Richmond Branch, 8060 Westminster Highway, Richmond, BC V6X 1A6 030800062 00062-308 GTA Main Branch, -

A Comparative Analysis of Major Suburban Shopping Nodes in Winnipeg

A Comparative Analysis of Major Suburban Shopping Nodes in Winnipeg Research Report # 40 Brian J. Lorch Department of Geography Lakehead University Thunder Bay, ON Institute of Urban Studies 2002 PUBLICATION DATA Lorch, Brian A Comparative Analysis of Major Suburban Shopping Nodes in Winnipeg Research Report # 40 ISBN: 1-894858-05-0 I. The University of Winnipeg, Institute of Urban Studies. II. Title. III. Series: Research Report (The University of Winnipeg, Institute of Urban Studies); 40 This publication was funded by the Institute of Urban Studies but the views expressed are the personal views of the author. The Institute accepts no responsibility for them. Published by: Institute of Urban Studies The University of Winnipeg 346 Portage Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 0C3 © 2002 ISBN: 1-894858-05-0 Institute of Urban Studies i Table of Contents List of Tables . iii List of Figures . iv Acknowledgements . v Executive Summary . vi Introduction 1 Big Box Store and Power Centre Development in Winnipeg 2 Research Objectives 4 Research Methods 5 Selection of Study Areas 5 Data Collection 7 Final Data Preparation 8 Findings 9 Morphological Attributes 10 Business Sector Mix 13 Big Box Stores 19 Vacancy Rates 20 Discussion 25 Locational Choices of Big Box Stores 25 Impact of Big Box Store and Power Centre Development 27 Conclusion 29 References 31 Appendices 33 A Study Area Boundaries 34 B Business Sector Classification Scheme 35 C Criteria for Identifying Big Box Stores 36 D Planned Shopping Centre Classification Scheme 37 ii List of Tables Table -

Ads Canadian Bank 343 Amex Bank Of

SECTION I NUMERIC LIST / LISTE NUMÉRIQUE 1 ADS CANADIAN BANK 343 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 034300012 00012-343 20 Queen Street West - Suite 2600, Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 034300092 00092-343 20 Queen Street West - Suite 2600, Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 AMEX BANK OF CANADA 303 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030300012 00012-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300022 00022-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300032 00032-303 101 McNabb Street, 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 BANK OF AMERICA NATIONAL ASSOCIATION 241 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 024101312 01312-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 024156792 56792-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 BANK OF CANADA 177 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 017700000 00000-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 017700006 00006-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 BANK OF CHINA (CANADA) 308 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030800012 00012-308 50 Minthorn BLVD-Suite 600, Markham, ON L3T 7X8 030800022 00022-308 Toronto Downtown -

Ads Canadian Bank 343 Amex Bank of Canada 303

SECTION I NUMERIC LIST / LISTE NUMÉRIQUE 1 ADS CANADIAN BANK 343 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 034300012 00012-343 20 Queen Street West - Suite 2600, Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 034300092 00092-343 20 Queen Street West - Suite 2600, Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 AMEX BANK OF CANADA 303 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030300012 00012-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300022 00022-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300032 00032-303 101 McNabb Street, 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 BANK OF AMERICA NATIONAL ASSOCIATION 241 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 024101312 01312-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 024156792 56792-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 BANK OF CANADA 177 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 017700000 00000-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 017700006 00006-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 BANK OF CHINA (CANADA) 308 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030800012 00012-308 50 Minthorn BLVD-Suite 600, Markham, ON L3T 7X8 030800022 00022-308 Toronto Downtown -

01-15-Mbrbnksn.Pdf

SECTION I NUMERIC LIST / LISTE NUMÉRIQUE 1 ADS CANADIAN BANK 343 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 034300012 00012-343 20 Queen Street West - Suite 2600, Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 034300092 00092-343 20 Queen Street West - Suite 2600, Toronto, ON M5H 3R3 AMEX BANK OF CANADA 303 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030300012 00012-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300022 00022-303 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 030300032 00032-303 101 McNabb Street, 101 McNabb Street, Markham, ON L3R 4H8 BANK OF AMERICA NATIONAL ASSOCIATION 241 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 024101312 01312-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 024156792 56792-241 Main Branch, 200 Front St. W., Suite 2700, Toronto, ON M5V 3L2 BANK OF CANADA 177 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 017700000 00000-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 017700006 00006-177 Banking Services, 245 Sparks Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G9 BANK OF CHINA (CANADA) 308 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 030800012 00012-308 50 Minthorn BLVD-Suite 600, Markham, ON L3T 7X8 030800022 00022-308 Toronto Downtown -

Available Online

PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION CITY OF WINNIPEG ARCHIVES DISCLAIMER: this finding aid was produced manually and may contain inaccuracies It is provided for reference purposes only and should not be copied or distributed Box File Item Description Date Format Photographer P01 1 Unidentified ca. 1900 Black and White Ralph Lilje-Gren Mayor and Aldermen of the City of P01 2 Black and White 750 Kildonan Dr, East Kildonan Winnipeg Alderman A. J. Reid, City of East Kildonan, as Honorary Fire P01 3 Black and White Captain, East Kildonan Fire Department Mayor G. N. Suttie, City of East P01 4 Kildonan, as Honorary Fire Chief, Black and White East Kildonan Fire Department P01 5 East Kildonan Municipal Offices Black and White L. B. Foote, 284 Crane and David, Bakers and P01 6 Black and White Main Street Confectioners Winnipeg Rainfall: 48 hours after rain. Main P01 7 July 8, 1932 Black and White Street at Balmont Rainfall: Rain fall June 29, 1932. P01 8 July 1, 1932 Black and White Main Street - Kilbridge to Burrin Rainfall: 48 hours after rain. Main P01 9 July 8, 1932 Black and White Street, south of Seven Oaks Rainfall. Main Street - Perth to P01 10 June 29, 1932 Black and White Hartford Rainfall: Main Street corner Seven P01 11 June 29, 1932 Black and White Oaks Rainfall: Main Street - Perth to P01 12 July 8, 1932 Black and White Hartford Rainfall: 48 hours after rain. Main P01 13 July 1, 1932 Black and White Street - Hartford to Balmont Condition south of Balmont, due to wet gutter. At this point, this gutter P01 14 July 9, 1932 Black and White has probably never been dry since the job was built. -

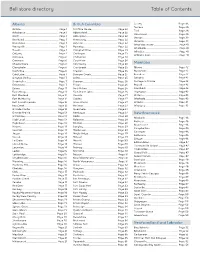

Bell Store Directory Table of Contents

Bell store directory Table of Contents Alberta British Columbia Surrey.................................................................. Page 36 Terrace ................................................................ Page 38 Airdrie ..................................................................... Page 1 100 Mile House ................................................ Page 22 Trail ....................................................................... Page 38 Athabasca ............................................................ Page 1 Abbotsford ........................................................ Page 22 Vancouver......................................................... Page 38 Banff ........................................................................ Page 1 Aldergrove ......................................................... Page 22 Vernon................................................................. Page 39 Barrhead ............................................................... Page 1 Armstrong .......................................................... Page 22 Victoria ............................................................... Page 39 Beaumont .............................................................. Page 1 Ashcroft ............................................................... Page 22 West Vancouver .............................................. Page 41 Bonnyville ............................................................. Page 1 Burnaby .............................................................. Page