Reagan Coopted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Iran National Intelligence Estimate: a Comprehensive Guide to What Is Wrong with the NIE James Phillips

No. 2098 January 11, 2008 The Iran National Intelligence Estimate: A Comprehensive Guide to What Is Wrong with the NIE James Phillips U.S. efforts to contain Iran and prevent it from attaining nuclear weapons have been set back by the release of part of the most recent National Intelligence Talking Points Estimate (NIE) on Iran’s nuclear program. “Iran: 1 • The National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) uses Nuclear Intentions and Capabilities,” the unclassi- a narrow definition of Iran’s nuclear weapons fied summary of the key judgments of the NIE, con- program that is so restrictive that even offi- tained a stunning bombshell: the conclusion that Iran cials from the normally cautious Interna- halted its nuclear weapons program in 2003. tional Atomic Energy Agency have expressed What prompted this reversal of intelligence analy- disagreement with its conclusions. sis is not known. The controversial report released on • The NIE mistakenly assumes that weaponiza- December 3, 2007, contained only a summary of key tion of the warhead is the key aspect of Iran’s judgments and excluded the evidence on which the nuclear program that constitutes a potential threat. judgments were made. However, many experts on intelligence, nuclear proliferation, and the Middle • The NIE understates the importance of East have charged that the NIE is critically flawed. Iran’s “civilian” uranium enrichment efforts to the development of nuclear weapons. This paper distills many of the criticisms against • The NIE does not address related military the Iran NIE and provides a list of articles for further developments, such as Iran’s ballistic missile reading on this important issue. -

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

Juliana Geran Pilon Education

JULIANA GERAN PILON [email protected] Dr. Juliana Geran Pilon is Research Professor of Politics and Culture and Earhart Fellow at the Institute of World Politics. For the previous two years, she taught in the Political Science Department at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. From January 1991 to October 2002, she was first Director of Programs, Vice President for Programs, and finally Senior Advisor for Civil Society at the International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES), after three years at the National Forum Foundation, a non-profit institution that focused on foreign policy issues - now part of Freedom House - where she was first Executive Director and then Vice President. At NFF, she assisted in creating a network of several hundred young political activists in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. For the past thirteen years she has also taught at Johns Hopkins University, the Institute of World Politics, George Washington University, and the Institute of World Politics. From 1981 to 1988, she was a Senior Policy Analyst at the Heritage Foundation, writing on the United Nations, Soviet active measures, terrorism, East-West trade, and other international issues. In 1991, she received an Earhart Foundation fellowship for her second book, The Bloody Flag: Post-Communist Nationalism in Eastern Europe -- Spotlight on Romania, published by Transaction, Rutgers University Press. Her autobiographical book Notes From the Other Side of Night was published by Regnery/Gateway, Inc. in 1979, and translated into Romanian in 1993, where it was published by Editura de Vest. A paperback edition appeared in the U.S. in May 1994, published by the University Press of America. -

The Tea Party Movement As a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 Albert Choi Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/343 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 by Albert Choi A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2014 i Copyright © 2014 by Albert Choi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. THE City University of New York iii Abstract The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 by Albert Choi Advisor: Professor Frances Piven The Tea Party movement has been a keyword in American politics since its inception in 2009. -

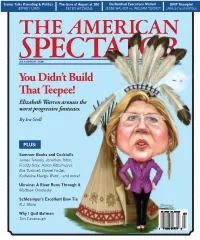

You Didn't Build That Teepee!

Trump Talks Parenting & Politics The Guns of August at 100 Do Botched Executions Matter? UKIP Triumphs! JEFFREY LORD PETER HITCHENS JESSE WALKER vs. WILLIAM TUCKER JAMES DELINGPOLE JULY/AUGUST 2014 A MONTHLY REVIEW EDITED BY R. EMMETT TYRRELL, JR. You Didn’t Build That Teepee! Elizabeth Warren arouses the worst progressive fantasies. By Ira Stoll PLUS: Summer Books and Cocktails James Taranto, Jonathan Tobin, Freddy Gray, Helen Rittelmeyer, Eve Tushnet, Daniel Foster, Katherine Mangu-Ward…and more! Ukraine: A River Runs Through It Matthew Omolesky Schlesinger’s Excellent Bow Tie R.J. Stove Why I Quit Batman Tim Cavanaugh 1 5 1 5 1 5 1 5 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 100 100 100 100 “ The best detector is not merely the one that can pick up radar from the farthest distance, although the Valentine One continues to score best.” — Autoweek Now V1 comes to a touchscreen near you. Introducing the Threat Picture You can see the arrows at work on your compatible iPhone® or AndroidTM device. Check it out… The app is free! Yo u can download V1connection, the app Where’s the radar? It’s in the Box. for free. Go to the app store on your device. When installed, the app automatically runs in Demo Mode. No need to link to V1. Analyze preloaded threat situations on three different screens: on the V1 screen, Arrow in the Box means a threat in the radar zone. on Picture, and on List. Then when you’re ready to put the Threat Picture on duty in your car, order the Bluetooth® communication module directly from us. -

The Weekly Standard…Don’T Settle for Less

“THE ORACLE OF AMERICAN POLITICS” — Wolf Blitzer, CNN …don’t settle for less. POSITIONING STATEMENT The Weekly Standard…don’t settle for less. Through original reporting and prose known for its boldness and wit, The Weekly Standard and weeklystandard.com serve an audience of more than 3.2 million readers each month. First-rate writers compose timely articles and features on politics and elections, defense and foreign policy, domestic policy and the courts, books, art and culture. Readers whose primary common interests are the political developments of the day value the critical thinking, rigorous thought, challenging ideas and compelling solutions presented in The Weekly Standard print and online. …don’t settle for less. EDITORIAL: CONTENT PROFILE The Weekly Standard: an informed perspective on news and issues. 18% Defense and 24% Foreign Policy Books and Arts 30% Politics and 28% Elections Domestic Policy and the Courts The value to The Weekly Standard reader is the sum of the parts, the interesting mix of content, the variety of topics, type of writers and topics covered. There is such a breadth of content from topical pieces to cultural commentary. Bill Kristol, Editor …don’t settle for less. EDITORIAL: WRITERS Who writes matters: outstanding political writers with a compelling point of view. William Kristol, Editor Supreme Court and the White House for the Star before moving to the Baltimore Sun, where he was the national In 1995, together with Fred Barnes and political correspondent. From 1985 to 1995, he was John Podhoretz, William Kristol founded a senior editor and White House correspondent for The new magazine of politics and culture New Republic. -

COURSE SYLLABUS US Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of Trump

COURSE SYLLABUS U.S. Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of Trump Central European University Fall 2020 4 Credits (8 ECTS Credits) Co-Instructors Erin Jenne, PhD Professor, International Relations Dept. [email protected] Levente Littvay, PhD Professor, Political Science Dept. [email protected] Teaching Assistants Michael Zeller, Doctoral Candidate, Political Science Dept. [email protected] Semir Dzebo Doctoral Candidate, International Relations Dept. [email protected] Important Note About the Course Format This course is designed for online delivery. It includes pre-recorded lectures, individual and group activities, a discussion forum where all class related questions can be discussed amongst the students and with the team of instructors. There is 1 hour and 40 minutes set aside each week for synchronous group activities. For these, if necessary, students will be grouped into a European morning (11 am - 12:40 pm CET) and evening (17:20 - 19:00 pm CET) session to accommodate potential timezone issues. (Around the time of the election, we may schedule more. And forget timezones, or sleep, on November 2, 3 and 4.) This course does not meet in person, but, nonetheless, the goal is to make it useful and fun. The course is open to CEU students on-site in Vienna or scattered anywhere across the globe. We welcome MA and PhD students from any department who wish to see the political science perspective on the elections and would like to get some hands on American Politics research experience. Course Description While most courses focus on either the domestic or the foreign policy aspect of U.S. -

The Tea Party Movement and Entelechy: an Inductive Study of Tea Party Rhetoric By

The Tea Party Movement and Entelechy: an Inductive Study of Tea Party Rhetoric By John Leyland Price M.A., Central Michigan University, 2013 B.S.B.A., Central Michigan University, 2010 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Communication Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Robert C. Rowland Dr. Beth Innocenti Dr. Brett Bricker Dr. Scott Harris Dr. Wayne Sailor Date Defended: 5 September 2019 ii The dissertation committee for John Leyland Price certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Tea Party Movement and Entelechy: an Inductive Study of Tea Party Rhetoric Chair: Dr. Robert C. Rowland Date Approved: 5 September 7 2019 iii Abstract On February 19, 2009, CNBC journalist Rick Santelli’s fiery outburst against the Obama Administration on national television gave the Tea Party Movement (TPM) its namesake. Soon after rallies were organized across the U.S. under the Tea Party banner. From its inception in 2009, the TPM became an essential player in U.S. politics and pivotal in flipping control of the Senate and House to the Republican Party during the 2010 midterm elections. The movement faced controversy on both sides of the political spectrum for its beliefs and fervent stance against compromising with political adversaries. Researchers argued that the TPM was an example of Richard Hofstadter’s Paranoid Style. Others claimed that the movement’s rhetoric, member demographics, and political success demonstrated it was outside the boundaries of the Paranoid Style. -

Rick Perry's Second

Perilous Pensions Why Israel Won’t Back Down Will Soccer Conquer American Sport? On Crime and Punishment STEVEN GREENHUT JONATHAN TOBIN PLESZCZYNSKI vs. THORNBERRY EVE TUSHNET SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2014 A MONTHLY REVIEW EDITED BY R. EMMETT TYRRELL, JR. Rick Perry’s Second Act Can this man win in 2016? By Jon Cassidy PLUS: Back-to-Campus Bonanza B.D. McClay and Bill McMorris Raul Labrador: The Negotiator Amanda C. Elliott Euphoria in the Bread Aisle Kyle Peterson Muriel’s Spark of Genius Lydia Sherwood Long-range radar protection you can trust: “Pure range is the Valentine’s domain.” — Autoweek Now Valentine One comes to a touchscreen near you. Three screens: analyze every threat three ways. You can see the arrows at work on the screen of any compatible iPhone® or AndroidTM device. Frequency and Direction of Priority Alert Profi les Menu V1 Dark Mode Mute Computer Modes Bogey Counter V1 Screen—shows Picture Screen—the List Screen—the all warnings including Threat Picture shows Threat List shows all arrows, Bogey Counter, the full width of all signals in range by and signal strength. activated bands and numerical frequency, Band ID Touch icons for Mute, arrows mark all signal each with an arrow Modes and V1 Dark. activity on them. showing Direction. Threat Swipe for Check it out… The app is free! Strength V1, Picture You can download V1connection, the app for free. and List Screens Go to the app store on your device. When installed, the app automatically runs a Demo Mode. No Beyond Situation Awareness need to link to V1. -

ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWS Since Inception of the Program in 1994

Update on the 141 ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWS Since Inception of the Program in 1994 24th Annual Robert Novak Journalism Fellowship Awards Dinner May 10, 2017 2017 ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWSHIP AWARD WINNERS HELEN R. ANDREWS | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “Eminent Boomers: The Worst Generation from Birth to Decadence” Helen earned a degree in religious studies from Yale University, where she served as speaker of the Yale Political Union. Currently a freelance writer and commentator, she served for three years as a policy analyst for the Centre for Independent Studies, a leading conservative think tank in suburban Sydney, Australia. Previously, she was an associate editor at National Review. Her work has appeared in First Things, Claremont Review of Books, The American Spectator, The Weekly Standard and others. MADISON E. ISZLER | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “What’s Killing Middle-Aged White Women—and What it Means for Society” Madison holds a master’s degree, cum laude, in political philosophy and economics from The King’s College. Currently, she is an Intercollegiate Studies Institute Reporting Fellow. She has interned for USA Today and the National Association of Scholars and was a reporter for the New York Post. Her work has appeared in numerous outlets, including the Raleigh News & Observer, Charlotte Observer, New York Post and Miami Herald. Originally from Florida, she resides in Raleigh, North Carolina. RYAN LOVELACE | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “Hiding in Plain Sight: Criminal Illegal Immigration in America” An Illinois native, Ryan attended and played football for the University of Wyoming. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in journalism from Butler University. -

Clinton, Conspiracism, and the Continuing Culture

TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL PublicEye RESEARCH ASSOCIATES SPRING 1999 • Volume XIII, No. 1 Clinton, Conspiracism, and the Continuing Culture War What is Past is Prologue by Chip Berlet cal of the direct-mail genre, it asked: culture war as part of the age-old battle he roar was visceral. A torrent of Which Clinton Administration against forces aligned with Satan. sound fed by a vast subconscious scandal listed below do you consider to Demonization is central to the process. Treservoir of anger and resentment. be “very serious”? Essayist Ralph Melcher notes that the “ven- Repeatedly, as speaker after speaker strode to The scandals listed were: omous hatred” directed toward the entire the podium and denounced President Clin- Chinagate, Monicagate, Travel- culture exemplified by the President and his ton, the thousands in the cavernous audito- gate, Whitewater, FBI “Filegate,” wife succeeded in making them into “polit- rium surged to their feet with shouts and Cattlegate, Troopergate, Casinogate, ical monsters,” but also represented the applause. The scene was the Christian Coali- [and] Health Caregate… deeper continuity of the right's historic tion’s annual Road to Victory conference held In addition to attention to scandals, distaste for liberalism. As historian Robert in September 1998—three months before the those attending the annual conference clearly Dallek of Boston University puts it, “The House of Representatives voted to send arti- opposed Clinton’s agenda on abortion, gay Republicans are incensed because they cles of impeachment to the Senate. rights, foreign policy, and other issues. essentially see Clinton…as the embodi- Former Reagan appointee Alan Keyes Several months later, much of the coun- ment of the counterculture’s thumbing of observed that the country’s moral decline had try’s attention was focused on the House of its nose at accepted wisdoms and institu- spanned two decades and couldn’t be blamed Representatives “Managers” and their pursuit tions of the country.” exclusively on Clinton, but when he of a “removal” of Clinton in the Senate. -

Neo-Conservatism and Foreign Policy

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2009 Neo-conservatism and foreign policy Ted Boettner University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Boettner, Ted, "Neo-conservatism and foreign policy" (2009). Master's Theses and Capstones. 116. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neo-Conservatism and Foreign Policy BY TED BOETTNER BS, West Virginia University, 2002 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science September, 2009 UMI Number: 1472051 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI" UMI Microform 1472051 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code.