Introduction to How Refrigerators Work the Purpose of Refrigeration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solar Heating and Cooling & Solar Air-Conditioning Position Paper

Task 53 New Generation Solar Cooling & Heating Systems (PV or solar thermally driven systems) Solar Heating and Cooling & Solar Air-Conditioning Position Paper November 2018 Contents Executive Summary ............................................................. 3 Introduction and Relevance ................................................ 4 Status of the Technology/Industry ...................................... 5 Technical maturity and basic successful rules for design .............. 7 Energy performance for PV and Solar thermally driven systems ... 8 Economic viability and environmental benefits .............................. 9 Market status .................................................................................... 9 Potential ............................................................................. 10 Technical potential ......................................................................... 10 Costs and economics ..................................................................... 11 Market opportunities ...................................................................... 12 Current Barriers ................................................................. 12 Actions Needed .................................................................. 13 This document was prepared by Daniel Neyer1,2 and Daniel Mugnier3 with support by Alexander Thür2, Roberto Fedrizzi4 and Pedro G. Vicente Quiles5. 1 daniel neyer brainworks, Oberradin 50, 6700 Bludenz, Austria 2 University of Innsbruck, Technikerstr. 13, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria -

Ammonia As a Refrigerant

1791 Tullie Circle, NE. Atlanta, Georgia 30329-2305, USA www.ashrae.org ASHRAE Position Document on Ammonia as a Refrigerant Approved by ASHRAE Board of Directors February 1, 2017 Expires February 1, 2020 ASHRAE S H A P I N G T O M O R R O W ’ S B U I L T E N V I R O N M E N T T O D A Y © 2017 ASHRAE (www.ashrae.org). For personal use only. Additional reproduction, distribution, or transmission in either print or digital form is not permitted without ASHRAE’s prior written permission. COMMITTEE ROSTER The ASHRAE Position Document on “Ammonia as a Refrigerant” was developed by the Society’s Refrigeration Committee. Position Document Committee formed on January 8, 2016 with Dave Rule as its chair. Dave Rule, Chair Georgi Kazachki IIAR Dayton Phoenix Group Alexandria, VA, USA Dayton, OH, USA Ray Cole Richard Royal Axiom Engineers, Inc. Walmart Monterey, CA, USA Bentonville, Arkansas, USA Dan Dettmers Greg Scrivener IRC, University of Wisconsin Cold Dynamics Madison, WI, USA Meadow Lake, SK, Canada Derek Hamilton Azane Inc. San Francisco, CA, USA Other contributors: M. Kent Anderson Caleb Nelson Consultant Azane, Inc. Bethesda, MD, USA Missoula, MT, USA Cognizant Committees The chairperson of Refrigerant Committee also served as ex-officio members: Karim Amrane REF Committee AHRI Bethesda, MD, USA i © 2017 ASHRAE (www.ashrae.org). For personal use only. Additional reproduction, distribution, or transmission in either print or digital form is not permitted without ASHRAE’s prior written permission. HISTORY of REVISION / REAFFIRMATION / WITHDRAWAL -

Investigating Absorption Refrigerator Fires (Part I)

Orion P. Keifer Peter D. Layson Charles A. Wensley Investigating Absorption Refrigerator Fires (Part I) ATLANTIC BEACH, FLORIDA—In today’s recreational vehicles (RV), the then expels it when perco- most common refrigerator uses absorption refrigeration technology, lated in the boiler. It is this primarily because this type of system can operate on multiple sources action of the water which of power, including propane when electrical power is unavailable. makes the ammonia flow. These refrigerators have been under intense scrutiny in recent years The hydrogen in the re- due to numerous reported fires, apparently starting in the area of the frigeration coil maintains absorption refrigerator. Both the Dometic Corporation and Norcold a positive pressure of ap- Incorporated, two manufacturers of RV refrigerators, have been re- proximately 300-375 PSI quired by the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (2.07-2.59 MPa) when (NHTSA) to recall certain models of refrigerators which have been not in operation and, due identified as capable of failing in a fire mode. In summary, the three to its low partial pressure, NHTSA recalls indicate a fatigue crack may develop in the boiler tube promotes the evaporation of the cooling unit which may release sufficient pressurized flammable of the liquid ammonia. It coolant solution into an area where an ignition source is present. The should be noted that unlike NHTSA Recall Campaign ID Numbers are 06E076000 for Dometic conventional refrigeration (926,877 affected units), and 02E019000 (28,144 affected units) and systems which extensively 02E045000 (8,419 affected units) for Norcold. use copper due to its high thermal conductivity, the Applications Engineering Group, Inc. -

Solar Air-Conditioning and Refrigeration - Achievements and Challenges

Solar air-conditioning and refrigeration - achievements and challenges Hans-Martin Henning Fraunhofer-Institut für Solare Energiesysteme ISE, Freiburg/Germany EuroSun 2010 September 28 – October 2, 2010 Graz - AUSTRIA © Fraunhofer ISE Outline Components and systems Achievements Solar thermal versus PV? Challenges and conclusion © Fraunhofer ISE Components and systems Achievements Solar thermal versus PV? Challenges and conclusion © Fraunhofer ISE Overall approach to energy efficient buildings Assure indoor comfort with a minimum energy demand 1. Reduction of energy demand Building envelope; ventilation 2. Use of heat sinks (sources) in Ground; outside air (T, x) the environment directly or indirectly; storage mass 3. Efficient conversion chains HVAC; combined heat, (minimize exergy losses) (cooling) & power (CH(C)P); networks; auxiliary energy 4. (Fractional) covering of the Solar thermal; PV; (biomass) remaining demand using renewable energies © Fraunhofer ISE Solar thermal cooling - basic principle Basic systems categories Closed cycles (chillers): chilled water Open sorption cycles: direct treatment of fresh air (temperature, humidity) © Fraunhofer ISE Open cycles – desiccant air handling units Solid sorption Liquid sorption Desiccant wheels Packed bed Coated heat exchangers Plate heat exchanger Silica gel or LiCl-matrix, future zeolite LiCl-solution: Thermochemical storage possible ECOS (Fraunhofer ISE) in TASK 38 © Fraunhofer ISE Closed cycles – water chillers or ice production Liquid sorption: Ammonia-water or Water-LiBr (single-effect or double-effect) Solid sorption: silica gel – water, zeolite-water Ejector systems Thermo-mechanical systems Turbo Expander/Compressor AC-Sun, Denmark in TASK 38 © Fraunhofer ISE System overview Driving Collector type System type temperature Low Open cycle: direct air treatment (60-90°C) Closed cycle: high temperature cooling system (e.g. -

A Review on Solar Powered Refrigeration and the Various Cooling Thermal Energy Storage (CTES) Systems

International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 2 Issue 2, February- 2013 A review on Solar Powered Refrigeration and the Various Cooling Thermal Energy Storage (CTES) Systems 1*Abhishek Sinha and 2 S. R Karale rd 1* Student, III Semester, M.Tech.Heat Power Engineering, 2 Professor Mechanical Engineering Department, G.H Raisoni College of Engineering, Nagpur-440016, India Abstract In this paper, a review has been conducted on various types of methods which are available for utilizing solar energy for refrigeration purposes. Solar refrigeration methods such as Solar Electric Method, Solar Mechanical Method and Solar Thermal Methods have been discussed. In solar thermal methods, various methods like Desiccant Refrigeration, Absorption Refrigeration and Adsorption Refrigeration has been discussed. All the methods have been assesed economically and environmentally and their operating characteristics have been compared to establish the best possible method for solar refrigeration. Also, the various available technologies for Cooling Thermal Energy Storage (CTES) have been discussed in this paper. Methods like Chilled Water Storage (CWS) and Ice Thermal Storage (ITS) have been compared and their advantages and disadvantages have been IJERTdiscussed.IJERT The results of the review reveal Solar Electric Method as the most promising method for solar refrigeration over the other methods. As far as CTES systems are concerned, ITS has advantage over other methods based on storage volume capability, but it has a comparatively lower COP than other available techniques. Keywords: Solar powered refrigeration, Solar Electric Method, Solar Mechanical Method, Solar Thermal Method, CTES system, Chilled Water Storage (CWS) system, ice TES systems, etc. -

Guide for Air Conditioning, Refrigeration, and Help the Student

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 251 645 CE 040 232 AUTHOR Henderson, William Edward, Jr., Ed. TITLE Art::culated, Performance-Based Instruction Objectives Guide for Air Conditioning, Refrigeration, and Heating. Volume II(Second Year). INSTITUTION Greenville County School District, Greenville, S.C.; Greenville Technical Coll., S. PUB DATE Oct 84 NOTE 374p.; Prepared by the Articulation Program Task Force Committee for Air Conditioning, Refrigeration, and Heating. PUB TYPE Guides Clasrroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTO. *Air Conditioning; Behavioral Objectives; Competency Based Education; Curriculum Guides; *Equipment Maintenance; Fuels; Jrade 12; *Heating; High Schools; Job Skills; Le.,zning Activities; *Refrigeration; Secondary Education; Solar Energy; Trade and Industrial Education; Units of Study; *Ventilation ABSTRACT This articulation guide contains 17 units of instruction for the second year of a two-year vocational program designed to prepare the high school graduate to install, maintain, and repair various types of residential and commercial heating, air conditioning, and refrigeration equipment. The units are designed to help the student to expand and apply the basic knowledge already mastered and to learn new principles and techniques and to prepare him/her for entry-level work as an apprentice. The seventeen units cover aid conditioning calculations (psychrometrics,residential heat loss and heat gain, duct design and sizing and air treatment); troubleshooting and servicing residential air conditioners; commercial refrigeration; commercial air conditioning; heating systems (electrical resistance heating, heat pumps, gas heating, oil heating, hydronics, solar heating systems); automotive air conditioner maintenance/repair; estimating and planning heating, ventilation, and air conditioning jobs; customer relations; and shop projects. -

Solar Cooling Used for Solar Air Conditioning - a Clean Solution for a Big Problem

Solar Cooling Used for Solar Air Conditioning - A Clean Solution for a Big Problem Stefan Bader Editor Werner Lang Aurora McClain csd Center for Sustainable Development II-Strategies Technology 2 2.10 Solar Cooling for Solar Air Conditioning Solar Cooling Used for Solar Air Conditioning - A Clean Solution for a Big Problem Stefan Bader Based on a presentation by Dr. Jan Cremers Figure 1: Vacuum Tube Collectors Introduction taics convert the heat produced by solar energy into electrical power. This power can be “The global mission, these days, is an used to run a variety of devices which for extensive reduction in the consumption of example produce heat for domestic hot water, fossil energy without any loss in comfort or lighting or indoor temperature control. living standards. An important method to achieve this is the intelligent use of current and Photovoltaics produce electricity, which can be future solar technologies. With this in mind, we used to power other devices, such as are developing and optimizing systems for compression chillers for cooling buildings. architecture and industry to meet the high While using the heat of the sun to cool individual demands.” Philosophy of SolarNext buildings seems counter intuitive, a closer look AG, Germany.1 into solar cooling systems reveals that it might be an efficient way to use the energy received When sustainability is discussed, one of the from the sun. On the one hand, during the time first techniques mentioned is the use of solar that heat is needed the most - during the energy. There are many ways to utilize the winter months - there is a lack of solar energy. -

Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Chronology

Air Conditioning and Refrigeration C H R O N O L O G Y Significant dates pertaining to Air Conditioning and Refrigeration revised May 4, 2006 Assembled by Bernard Nagengast for American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers Additions by Gerald Groff, Dr.-Ing. Wolf Eberhard Kraus and International Institute of Refrigeration End of 3rd. Century B.C. Philon of Byzantium invented an apparatus for measuring temperature. 1550 Doctor, Blas Villafranca, mentioned process for cooling wine and water by adding potassium nitrate About 1597 Galileo’s ‘air thermoscope’ Beginning of 17th Century Francis Bacon gave several formulae for refrigeration mixtures 1624 The word thermometer first appears in literature in a book by J. Leurechon, La Recreation Mathematique 1631 Rey proposed a liquid thermometer (water) Mid 17th Century Alcohol thermometers were known in Florence 1657 The Accademia del Cimento, in Florence, used refrigerant mixtures in scientific research, as did Robert Boyle, in 1662 1662 Robert Boyle established the law linking pressure and volume of a gas a a constant temperature; this was verified experimentally by Mariotte in 1676 1665 Detailed publication by Robert Boyle with many fundamentals on the production of low temperatures. 1685 Philippe Lahire obtained ice in a phial by enveloping it in ammonium nitrate 1697 G.E. Stahl introduced the notion of “phlogiston.” This was replaced by Lavoisier, by the “calorie.” 1702 Guillaume Amontons improved the air thermometer; foresaw the existence of an absolute zero of temperature 1715 Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit developed mercury thermoneter 1730 Reamur introduced his scale on an alcohol thermometer 1742 Anders Celsius developed Centigrade Temperature Scale, later renamed Celsius Temperature Scale 1748 G. -

Verification of a Level-3 Diesel Emissions Control Strategy for Transport Refrigeration Units

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2010 Verification of a level-3 diesel emissions control strategy for transport refrigeration units Umesh Shewalla West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Shewalla, Umesh, "Verification of a level-3 diesel emissions control strategy for transport refrigeration units" (2010). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 2132. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/2132 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Verification of a Level-3 Diesel Emissions Control Strategy for Transport Refrigeration Units Umesh Shewalla Thesis submitted to the College of Engineering and Mineral Resources at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Mechanical Engineering -

Refrigeration Fundamentals of Refrigeration

Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 Major Seminar Topics ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Issues for Refrigeration Facilities ........................................................................................ 3 Users of Refrigeration ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Refrigeration Classifications ............................................................................................................................... 4 Typical Supermarket Electrical Usage ............................................................................................................... 5 Typical Commercial and Industrial Electrical Usage .......................................................................................... 5 Integrated Demand Side Management (IDSM) .................................................................................................. 6 What is Title 24?............................................................................................................................................... 22 Reasons for Using Refrigeration ...................................................................................................................... 23 Refrigeration Units in California ...................................................................................................................... -

Managing Humidity in Cold Store Installations

MANAGING HUMIDITY IN COLD STORE INSTALLATIONS COTES.COM MANAGING HUMIDITY IN COLD STORE INSTALLATIONS COTES.COM HUMIDITY – THE INVISIBLE PART OF THE CONTROL EQUATIONS DIFFICULTIES GET DEALT WITH Cooling goods for low-temperature storage can often lead to big problems with unwanted ice and condensation – all caused by humidity. Humidity is is an invisible parameter that can ratch up operating costs and punch big holes in customer satisfaction. Cotes adsorption dehumidifier solutions enable you to tackle the fundamental reasons why ice and condensation even arise – giving you full control over conditions, lower operating costs and greater customer satisfaction. COTES.COM CONTENTS 07 TARGETING SYMPTOMS OR ROOT CAUSES? 08 Do you have a humidity problem? 13 PRACTICAL ISSUES COMMON IN COLD STORE SET-UPS 14 Where ice and condensation form 16 A plethora of practical problems 18 Have you got problems with ice and condensation? 23 NO TWO COLD STORE SET-UPS ARE THE SAME 24 Your challenges are unique 26 What needs to be considered? 28 Different conditions – different solutions 30 Different refrigeration and freezing set-ups 33 HOW TO TACKLE ICE AND CONDENSATION 34 Defrosting makes a difference 38 The dehumidification approach 39 How it works 40 What does it cost? 41 What really happens? 42 How it’s installed 47 Recommended action 49 HOW COTES CAN HELP 50 Cotes recommends 54 Prevention is better than cure 56 Effective humidity management brings down your operating costs 57 The benefits add up 58 Cotes All-round 59 Cotes Flexible 61 EXPERTS IN MANAGING HUMIDITY TARGETING SYMPTOMS OR ROOT CAUSES? DIFFICULTIES GET DEALT WITH SYMPTOMS OR CAUSES? Cooling goods for low-temperature storage can often The problem is that this is only dealing with the lead to problems because humidity present in the air symptoms – not the root causes. -

Chapter 10: Refrigeration Cycles

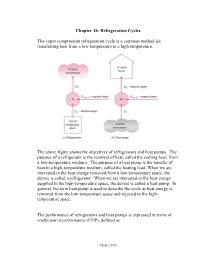

Chapter 10: Refrigeration Cycles The vapor compression refrigeration cycle is a common method for transferring heat from a low temperature to a high temperature. The above figure shows the objectives of refrigerators and heat pumps. The purpose of a refrigerator is the removal of heat, called the cooling load, from a low-temperature medium. The purpose of a heat pump is the transfer of heat to a high-temperature medium, called the heating load. When we are interested in the heat energy removed from a low-temperature space, the device is called a refrigerator. When we are interested in the heat energy supplied to the high-temperature space, the device is called a heat pump. In general, the term heat pump is used to describe the cycle as heat energy is removed from the low-temperature space and rejected to the high- temperature space. The performance of refrigerators and heat pumps is expressed in terms of coefficient of performance (COP), defined as Chapter 10-1 Desired output Cooling effect QL COPR === Required input Work input Wnet, in Desired output Heating effect QH COPHP === Required input Work input Wnet, in Both COPR and COPHP can be larger than 1. Under the same operating conditions, the COPs are related by COPHP=+ COP R 1 Can you show this to be true? Refrigerators, air conditioners, and heat pumps are rated with a SEER number or seasonal adjusted energy efficiency ratio. The SEER is defined as the Btu/hr of heat transferred per watt of work energy input. The Btu is the British thermal unit and is equivalent to 778 ft-lbf of work (1 W = 3.4122 Btu/hr).