Integrated Approaches for Roma Integration (2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Crime Prevention Network (EUCPN) Annex І Approved by the Management Board of the Network in 2018

European Crime Prevention Network (EUCPN) Annex І Approved by the Management board of the network in 2018 Please fill in the form in English in accordance with the ECPA criteria included in the "Rules and procedures for awarding and presenting the European Crime Prevention Award" GENERAL INFORMATION • Please indicate your country Republic of Bulgaria • Is it an official application or is it an additional project? The project is an official application 3. Project name „With a thought for the future“ 4. Project manager. Contacts Senior Commissioner Dimitar Mashov – Director of the Regional Directorate of the MoI – V.Tarnovo, 062 662250 5. Project start date. Is the project active? If not, please indicate the end date. The demographic situation in our country and in particular in V. Tarnovo District is characterized by a continuing decline and aging of the population, and this circumstance is among the victimogenic factors, especially for the elderly in remote areas. Imbalances as a result of the economic recession, low birth rates among groups with high social status and huge birth rates among marginalized communities are changing the structure of society The area is home to various Roma community groups - yerli, rudari, kaldarashi and millet. The largest compact Roma communities are in the town of G. Oryahovitsa, the town of Pavlikeni, the town of Polski Trambesh and the town of Strazhitsa. Typical crimes committed by this community are crimes against property - telephone fraud, pickpocketing, theft of ferrous and nonferrous metals, etc. Prevention is targeted at all crimes committed, but special emphasis is placed on combating organized group crime, which characterizes part of the community and its way of life. -

Annex REPORT for 2019 UNDER the “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY of the REPUBLIC of BULGAR

Annex REPORT FOR 2019 UNDER THE “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2012 - 2020 Operational objective: A national monitoring progress report has been prepared for implementation of Measure 1.1.2. “Performing obstetric and gynaecological examinations with mobile offices in settlements with compact Roma population”. During the period 01.07—20.11.2019, a total of 2,261 prophylactic medical examinations were carried out with the four mobile gynaecological offices to uninsured persons of Roma origin and to persons with difficult access to medical facilities, as 951 women were diagnosed with diseases. The implementation of the activity for each Regional Health Inspectorate is in accordance with an order of the Minister of Health to carry out not less than 500 examinations with each mobile gynaecological office. Financial resources of BGN 12,500 were allocated for each mobile unit, totalling BGN 50,000 for the four units. During the reporting period, the mobile gynecological offices were divided into four areas: Varna (the city of Varna, the village of Kamenar, the town of Ignatievo, the village of Staro Oryahovo, the village of Sindel, the village of Dubravino, the town of Provadia, the town of Devnya, the town of Suvorovo, the village of Chernevo, the town of Valchi Dol); Silistra (Tutrakan Municipality– the town of Tutrakan, the village of Tsar Samuel, the village of Nova Cherna, the village of Staro Selo, the village of Belitsa, the village of Preslavtsi, the village of Tarnovtsi, -

1 I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and List of Rural Municipalities in Bulgaria

I. ANNEXES 1 Annex 6. Map and list of rural municipalities in Bulgaria (according to statistical definition). 1 List of rural municipalities in Bulgaria District District District District District District /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality /Municipality Blagoevgrad Vidin Lovech Plovdiv Smolyan Targovishte Bansko Belogradchik Apriltsi Brezovo Banite Antonovo Belitsa Boynitsa Letnitsa Kaloyanovo Borino Omurtag Gotse Delchev Bregovo Lukovit Karlovo Devin Opaka Garmen Gramada Teteven Krichim Dospat Popovo Kresna Dimovo Troyan Kuklen Zlatograd Haskovo Petrich Kula Ugarchin Laki Madan Ivaylovgrad Razlog Makresh Yablanitsa Maritsa Nedelino Lyubimets Sandanski Novo Selo Montana Perushtitsa Rudozem Madzharovo Satovcha Ruzhintsi Berkovitsa Parvomay Chepelare Mineralni bani Simitli Chuprene Boychinovtsi Rakovski Sofia - district Svilengrad Strumyani Vratsa Brusartsi Rodopi Anton Simeonovgrad Hadzhidimovo Borovan Varshets Sadovo Bozhurishte Stambolovo Yakoruda Byala Slatina Valchedram Sopot Botevgrad Topolovgrad Burgas Knezha Georgi Damyanovo Stamboliyski Godech Harmanli Aitos Kozloduy Lom Saedinenie Gorna Malina Shumen Kameno Krivodol Medkovets Hisarya Dolna banya Veliki Preslav Karnobat Mezdra Chiprovtsi Razgrad Dragoman Venets Malko Tarnovo Mizia Yakimovo Zavet Elin Pelin Varbitsa Nesebar Oryahovo Pazardzhik Isperih Etropole Kaolinovo Pomorie Roman Batak Kubrat Zlatitsa Kaspichan Primorsko Hayredin Belovo Loznitsa Ihtiman Nikola Kozlevo Ruen Gabrovo Bratsigovo Samuil Koprivshtitsa Novi Pazar Sozopol Dryanovo -

175 Churches and Monasteries – Objects Of

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________ DERMENDZHIEV, Athanas,; DOYKOV, Martin (2017). The Churches and Monasteries – objects of religious tourism in the district of Veliko …. The Overarching Issues of the European Space: Society, Economy and Heritage in a Scenario … Porto: FLUP, pp. 175‐183 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CHURCHES AND MONASTERIES – OBJECTS OF RELIGIOUS TOURISM IN THE DISTRICT OF VELIKO TARNOVO (BULGARIA) Athanas DERMENDZHIEV Department of Geography, Faculty of History, “St. Cyril and St. Methodius” University of Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria [email protected] Martin DOYKOV Department of Geography, Faculty of History, “St. Cyril and St. Methodius” University of Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria. [email protected] Abstract The need of focusing on the significance of religious tourist sites and objects in the region of Veliko Tarnovo is provoked by socio-economic necessities. The last presume activation of cultural-historical resources with a view to the interest to the available objects. Religion, as spirit and interaction, presumes corresponding objectification. The last one is a segment in the formation of religious-tourist bank for its exploitation in spiritual-nationalistic direction. Recognized by Bulgarians as an ozonizing areal, the region of Veliko Tarnovo presumes fixing on values of cultural-historical content. Their studying and the explanation of their existence -

Network Program Democracy

Democracy Network Program DemNet II: Building Civil Society in Bulgaria Final Report Democracy Network Program DemNet II: Building Civil Society in Bulgaria 1998-2002 FINAL REPORT TO THE U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT Cooperative Agreement No. 181-A-00-98-00320-00 Institute for Sustainable Communities 535 Stone Cutters Way, Montpelier, VT 05602 USA Phone 802-229-2900 | Fax 802-229-2919 [email protected] | www.iscvt.org April 2003 Photos, front and back inside covers: Bulgarian landscapes; next page: DemNet-supported activities of SO partners and NGOs working for positive change in Bulgaria. Table of Contents I. Executive Summary • 6 II. The Context • 8 III. Program Design & Goals • 9 IV. Strengthening the Capacity of SO Partners • 11 • SELECTING SUPPORT ORGANIZATION PARTNERS • ORGANIZATIONAL STRENGTHENING • DEEPENING PROGRAM IMPACT • KEY OUTCOMES IN DEMNET’S FUNCTIONAL AREAS V. SO Partner Performance Stories • 22 VI. Supporting a Vibrant NGO Sector & Strengthening Civil Society in Bulgaria • 24 • TARGETING UNDERSERVED POPULATIONS & IMPROVING SOCIAL SAFETY NETS • CREATING ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY • NETWORKING & COALITION BUILDING FOR SUPPORT & SUSTAINABILITY • STRENGTHENING OUTREACH & PUBLIC RELATIONS • INCREASING CITIZEN PARTICIPATION IN POLICY DIALOGUE VII. Lessons Learned • 27 VIII. Conclusion • 29 IX. Attachments A: DEMNET SO PARTNER PUBLICATION B: SO PARTNER SUMMARIES C: ORGANIZATIONAL STRENGTHENING & PERFORMANCE MONITORING COMPONENTS D: SERVICE QUALITY REVIEW REPORT E: DONOR SURVEY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY F: ENGAGE INITIATIVE REPORT G: TRAVEL NOTES PUBLICATION (ENGAGE INITIATIVE) H: VOICES FOR CHANGE PUBLICATION I: ADVOCACY INITIATIVE REPORT J: LEADING LIGHTS PUBLICATION K: SUMMARY OF NGO GRANTEES L: SENSE OF EMPOWERMENT VIDEO Acknowledgements The success of any project is in the hands of many people—the SO partners, the capable and dedicated ISC staff in Bulgaria, many excellent consultants who supported the program, and the Bulgaria USAID mission that provided sound support and counsel at critical junctures. -

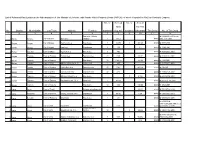

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry Of

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry of Defence, with Private Public Property Deeds (PPPDs), of which Property the MoD is Allowed to Dispose No. of Built-up No. of Area of Area the Plot No. District Municipality City/Town Address Function Buildings (sq. m.) Facilities (decares) Title Deed No. of Title Deed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Part of the Military № 874/02.05.1997 for the 1 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Slaveykov Hospital 1 545,4 PPPD whole real estate 2 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Kapcheto Area Storehouse 6 623,73 3 29,143 PPPD № 3577/2005 3 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Sarafovo Storehouse 6 439 5,4 PPPD № 2796/2002 4 Burgas Nesebar Town of Obzor Top-Ach Area Storehouse 5 496 PPPD № 4684/26.02.2009 5 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Honyat Area Barracks area 24 9397 49,97 PPPD № 4636/12.12.2008 6 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Storehouse 18 1146,75 74,162 PPPD № 1892/2001 7 Burgas Sozopol Town of Atiya Military station, by Bl. 11 Military club 1 240 PPPD № 3778/22.11.2005 8 Burgas Sredets Town of Sredets Velikin Bair Area Barracks area 17 7912 40,124 PPPD № 3761/05 9 Burgas Sredets Town of Debelt Domuz Dere Area Barracks area 32 5785 PPPD № 4490/24.04.2008 10 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Ahtopol Mitrinkovi Kashli Area Storehouse 1 0,184 PPPD № 4469/09.04.2008 11 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Tsarevo Han Asparuh Str., Bl. -

Priority Public Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste

Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Develonment Europe and Central Asia Region 32051 BULGARIA Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL SEQUENCING STRATEGIES FOR EU ACCESSION PriorityPublic Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste *t~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Public Disclosure Authorized IC- - ; s - o Fk - L - -. Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized May 2004 - "Wo BULGARIA ENVIRONMENTAL SEQUENCING STRATEGIES FOR EU ACCESSION Priority Public Investments for Wastewater Treatment and Landfill of Waste May 2004 Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Europe and Central Asia Region Report No. 27770 - BUL Thefindings, interpretationsand conclusions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Coverphoto is kindly provided by the external communication office of the World Bank County Office in Bulgaria. The report is printed on 30% post consumer recycledpaper. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................... i Abbreviations and Acronyms ..................................................................... ii Summary ..................................................................... iiM Introduction.iii Wastewater.iv InstitutionalIssues .xvi Recommendations........... xvii Introduction ...................................................................... 1 Part I: The Strategic Settings for -

Health Insurance Actpdf / 7.08 MB

Health Insurance Act Promulgated, State Gazette No. 70/19.06.1998, amended, SG No. 93/11.08.1998, SG No. 153/23.12.1998, effective 1.01.1999, SG No. 62/9.07.1999, SG No. 65/20.07.1999, amended and supplemented, SG No. 67/27.07.1999, effective 28.08.1999, amended, SG No. 69/3.08.1999, effective 3.08.1999, amended and supplemented, SG No. 110/17.12.1999, effective 1.01.2000, SG No. 113/28.12.1999, SG No. 64/4.08.2000, effective 1.10.2001, supplemented, SG No. 41/24.04.2001, effective 24.04.2001, amended and supplemented, SG No. 1/4.01.2002, effective 1.01.2002, SG No. 54/31.05.2002, effective 1.12.2002, supplemented, SG No. 74/30.07.2002, effective 1.01.2003, amended and supplemented, SG No. 107/15.11.2002, supplemented, SG No. 112/29.11.2002, amended and supplemented, SG No. 119/27.12.2002, effective 1.01.2003, amended, SG No. 120/29.12.2002, effective 1.01.2003, amended and supplemented, SG No. 8/28.01.2003, effective 1.03.2003, supplemented, SG No. 50/30.05.2003, amended, SG No. 107/9.12.2003, effective 9.12.2003, supplemented, SG No. 114/30.12.2003, effective 1.01.2004, amended and supplemented, SG No. 28/6.04.2004, effective 6.04.2004, supplemented, SG No. 38/11.05.2004, amended and supplemented, SG No. 49/8.06.2004, amended, SG No. 70/10.08.2004, effective 1.01.2005, amended and supplemented, SG No. -

The 10 Concepts for Local Economic Development Have Been Selected, Which Will Receive Funding for Implementation Under the GALOP Project

“Local Development, Poverty Reduction and Enhanced Inclusion of Vulnerable Groups” Programme The 10 concepts for local economic development have been selected, which will receive funding for implementation under the GALOP project On 30 October 2020 the evaluation of the 41 concepts for local economic development presented was completed. Based on these concepts the municipalities will apply for support under Project No. BGLD-1.002-0001 “Growth through activation of the local potential - GALOP”, implemented by the National Association of the Municipalities in the Republic of Bulgaria (NAMRB). The 10 finalists were selected by the Interdepartmental Commission, which included experts from the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities, the Programme Operator of” Local Development, Poverty Reduction and Improved Inclusion of Vulnerable Groups” Programme under the European Economic Area (EEA) Financial Mechanism 2014 - 2021, and the National Coordination Unit with the Council of Ministers, in addition to the Association representatives. They will have the opportunity to receive financial support for the implementation of their concepts of local economic development. The project, which the NAMRB is working on together with the Norwegian Association of Local Authorities, aims to draw the attention of municipalities to a realistic assessment of local conditions and help achieve their potential for socio-economic development. The opportunities provided by the project provoked a great interest during the competition, and the presented -

The Restructuring and Conversion of the Bulgarian Defense Industry During the Transition Period

BONN INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR CONVERSION . INTERNATIONALES KONVERSIONSZENTRUM BONN paper 22 The Restructuring and Conversion of the Bulgarian Defense Industry during the Transition Period July 2002 BONN INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR CONVERSION . INTERNATIONALES KONVERSIONSZENTRUM BONN The Restructuring and Conversion of the Bulgarian Defense Industry during the Transition Period By Dimitar Dimitrov Published by BICC, Bonn 2002 The Restructuring and Conversion of the Bulgarian Defense Industry Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Introduction 4 Theoretical Background of the Study 6 Particular characteristics of socialist defense enterprises 11 Historical overview 12 The Defense Industry After WWII 13 The Defense Industry in the 1970s and 80s 16 Planning processes, state bodies and procedures during socialism 18 The Structure of the Bulgarian MIC 19 Initial Conditions for Transformation 23 The Restructuring of the Defense Industry 26 Factors and strategies for conversion 26 Organizational restructuring and downsizing 30 Product restructuring 36 Management and personnel restructuring 39 Privatization 40 State Policies and Regulations 46 State Defense Industrial Policy: Pros and Cons 46 Government Regulations and State Bodies 50 The Role of the MoD 54 The Arms trade 56 1 Dimitar Dimitrov R&D and Innovations 58 Foreign cooperation 62 The Conversion of Bulgaria’s Defense Industry 65 The Role of the State in the Conversion Process 67 The Background of Companies Slated for Conversion in Bulgaria 71 Conversion in the 1990s 74 What next? 78 Conclusion: -

Revista Inclusiones Issn 0719-4706 Volumen 8 – Número Especial – Enero/Marzo 2021

CUERPO DIRECTIVO Mg. Amelia Herrera Lavanchy Universidad de La Serena, Chile Director Dr. Juan Guillermo Mansilla Sepúlveda Mg. Cecilia Jofré Muñoz Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile Universidad San Sebastián, Chile Editor Mg. Mario Lagomarsino Montoya Alex Véliz Burgos Universidad Adventista de Chile, Chile Obu-Chile, Chile Dr. Claudio Llanos Reyes Editor Científico Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile Dr. Luiz Alberto David Araujo Pontificia Universidade Católica de Sao Paulo, Brasil Dr. Werner Mackenbach Universidad de Potsdam, Alemania Editor Europa del Este Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica Dr. Alekzandar Ivanov Katrandhiev Universidad Suroeste "Neofit Rilski", Bulgaria Mg. Rocío del Pilar Martínez Marín Universidad de Santander, Colombia Cuerpo Asistente Ph. D. Natalia Milanesio Traductora: Inglés Universidad de Houston, Estados Unidos Lic. Pauline Corthorn Escudero Editorial Cuadernos de Sofía, Chile Dra. Patricia Virginia Moggia Münchmeyer Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile Portada Lic. Graciela Pantigoso de Los Santos Ph. D. Maritza Montero Editorial Cuadernos de Sofía, Chile Universidad Central de Venezuela, Venezuela COMITÉ EDITORIAL Dra. Eleonora Pencheva Universidad Suroeste Neofit Rilski, Bulgaria Dra. Carolina Aroca Toloza Universidad de Chile, Chile Dra. Rosa María Regueiro Ferreira Universidad de La Coruña, España Dr. Jaime Bassa Mercado Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile Mg. David Ruete Zúñiga Universidad Nacional Andrés Bello, Chile Dra. Heloísa Bellotto Universidad de Sao Paulo, Brasil Dr. Andrés Saavedra Barahona Universidad San Clemente de Ojrid de Sofía, Bulgaria Dra. Nidia Burgos Universidad Nacional del Sur, Argentina Dr. Efraín Sánchez Cabra Academia Colombiana de Historia, Colombia Mg. María Eugenia Campos Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México Dra. Mirka Seitz Universidad del Salvador, Argentina Dr. -

LBGO Charting UTM35 2020

AIP РЕПУБЛИКА БЪЛГАРИЯ LBGO AD 2 - 59.1 AIP REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 05 NOV 20 VASIS VISUAL APPROACH TRANSITION ALT 12000 FT AD ELEV 283 - 10 hPa TWR 133.500 246.825 ATIS 127.130 GORNA ORYAHOVITSA TRANSITION HGT (11717) FT RWY 09 - PAPI 3.0° MEHT 50 DUAL 124.500 CHART - ICAO ARP 43 09 06 N 025 42 43 E VFR ROUTES TRANSITION LEVEL BY ATC RWY 27 - PAPI 3.0° MEHT 50 DUAL 121.500 243.000 Karantsi Palamartsa Dryanovets Osikovo Karaisen Polski Trambesh Kardam Slomer Klimentovo TRA 41 Kovachevets Levski 25 TMZ/RMZ FL245 26 ABARU Orlovets GND 10500 Voditsa R-336/ 12.8 GRN 1 E Batak Radanovo 500 AGL Popovo 58 ' 5 . Vinograd ° Lom Cherkovna Asenovtsi 6 Obedinenie e Ivancha g n Gradishte a Nova Varbovka h c ° Lozen Posabina Medovina M f 246 020 Dolna Lipnitsa BEMKO o 2 A V Nedan e - TRA 74 Polski Senovets X R-044/ 17.0 GRN t 6 Kamen 6 a E 76 r FL245 12 Paisiy . ° 675 Gorna Lipnitsa 6 l Butovo Petko Strelets V 6 a GND 1800 0 AX R 0 Karavelovo M 0 Nikolaevo Patresh 16. nnu Slavyanovo DEKUN Stefan VA A R-284/ 19.8 GRN Stambolovo Gorski Senovets Zvezda V 675 Kutsina 33 Asenovo 087 MAX 1500 8 ° ° 16 ° Aprilovo .4 066 Sushitsa Goritsa Daskot Paskalevets 268° Varbovka Krusheto Tsarski izvor Nikyup 141 Pavlikeni BEGLO ° 1000 M Mirovo 1007 R-334/ 6.2 GRN V AX 676 Lesicheri Gorski Stambolovo 4 1200 Vodoley . Dimcha Dichin 7 Strazhitsa Byala Draganovo goren - cherkva dolen Rositsa Yantra Novo gradishte Suhindol Resen 321 Trambesh Razdeltsi Bryagovitsa Blagoevo TMA Mihaltsi ° DIDKI GORNA TMA Polikraishte Vladislav 492 R-007/ 2.0 GRN Varbitsa C 12500 Dobrotitsa