Guam: U.S. Defense Deployments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Ships and Submarines of the United States Navy

AIRCRAFT CARRIER DDG 1000 AMPHIBIOUS Multi-Purpose Aircraft Carrier (Nuclear-Propulsion) THE U.S. NAvy’s next-GENERATION MULTI-MISSION DESTROYER Amphibious Assault Ship Gerald R. Ford Class CVN Tarawa Class LHA Gerald R. Ford CVN-78 USS Peleliu LHA-5 John F. Kennedy CVN-79 Enterprise CVN-80 Nimitz Class CVN Wasp Class LHD USS Wasp LHD-1 USS Bataan LHD-5 USS Nimitz CVN-68 USS Abraham Lincoln CVN-72 USS Harry S. Truman CVN-75 USS Essex LHD-2 USS Bonhomme Richard LHD-6 USS Dwight D. Eisenhower CVN-69 USS George Washington CVN-73 USS Ronald Reagan CVN-76 USS Kearsarge LHD-3 USS Iwo Jima LHD-7 USS Carl Vinson CVN-70 USS John C. Stennis CVN-74 USS George H.W. Bush CVN-77 USS Boxer LHD-4 USS Makin Island LHD-8 USS Theodore Roosevelt CVN-71 SUBMARINE Submarine (Nuclear-Powered) America Class LHA America LHA-6 SURFACE COMBATANT Los Angeles Class SSN Tripoli LHA-7 USS Bremerton SSN-698 USS Pittsburgh SSN-720 USS Albany SSN-753 USS Santa Fe SSN-763 Guided Missile Cruiser USS Jacksonville SSN-699 USS Chicago SSN-721 USS Topeka SSN-754 USS Boise SSN-764 USS Dallas SSN-700 USS Key West SSN-722 USS Scranton SSN-756 USS Montpelier SSN-765 USS La Jolla SSN-701 USS Oklahoma City SSN-723 USS Alexandria SSN-757 USS Charlotte SSN-766 Ticonderoga Class CG USS City of Corpus Christi SSN-705 USS Louisville SSN-724 USS Asheville SSN-758 USS Hampton SSN-767 USS Albuquerque SSN-706 USS Helena SSN-725 USS Jefferson City SSN-759 USS Hartford SSN-768 USS Bunker Hill CG-52 USS Princeton CG-59 USS Gettysburg CG-64 USS Lake Erie CG-70 USS San Francisco SSN-711 USS Newport News SSN-750 USS Annapolis SSN-760 USS Toledo SSN-769 USS Mobile Bay CG-53 USS Normandy CG-60 USS Chosin CG-65 USS Cape St. -

The Creed of the USSVI Is Not to Forget Our Purpose……

USSVI — Blueback Base Newsletter Blueback Base, P.O. Box 1887 Portland, Oregon — January 2010 # 190 Clackamas, OR 97015-1887 The Creed of the USSVI is Not to Forget our Purpose…… “To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who gave their lives in the pursuit of duties while serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of motivation toward greater accomplishments, Pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of America and its Constitution.” BASE MEETINGS... FORWARD BATTERY BASE COMMANDER: Executive Board Will Meet: Chuck Nelson 360-694-5069 VICE COMMANDER: Thursday, 14 January 2010 Gary Webb 503-632-6259 VFW Post #4248 SECRETARY: 7118 S.E. Fern—Portland Dave Vrooman 503-262-8211 1730 TREASURER: Collie Collins 503-254-6750 CHAPLAIN: Blueback Base Meeting: Scott Duncan 503-667-0728 CHIEF OF THE BOAT: Thursday, 14 January 2010 Stu Crosby 503-390-1451 VFW Post #4248 WAYS AND MEANS CHAIRMAN: 7118 S.E. Fern—Portland Mike LaPan 503-655-7797 1900 MEMBERSHIP CHAIRMAN: Dave Vrooman 503-262-8211 PUBLICITY AND SOCIAL CHAIRMAN: LeRoy Vick 503-367-6087 BYLAWS CHAIRMAN: Chris Stafford 503-632-4535 The Lighter Side 6 SMALL STORES BOSS: Fittings — Lines? 6 Sandy Musa 503-387-5055 USSVI National Election 6 TRUSTEE: Mtg. Minutes 2 Five Years Ago 7 Fred Carneau 503-654-0451 SANITARY EDITOR: Dues Chart 2 Another Skipper Relieved 7 Dave Vrooman 503-262-8211 USSVWWII-USSVI Luncheon 2 New Escape Trainer 7 [email protected] Dink List 2 New Year’s Log 8 NOMINATION COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN: Ray Lough 360-573-4274 2010 Census—Cautions 2 Operation Petticoat 8 PAST BASE COMMANDER: Support Our Troops 3 Commission Pennant 9 J.D. -

Appendix As Too Inclusive

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Appendix I A Chronological List of Cases Involving the Landing of United States Forces to Protect the Lives and Property of Nationals Abroad Prior to World War II* This Appendix contains a chronological list of pre-World War II cases in which the United States landed troops in foreign countries to pro- tect the lives and property of its nationals.1 Inclusion of a case does not nec- essarily imply that the exercise of forcible self-help was motivated solely, or even primarily, out of concern for US nationals.2 In many instances there is room for disagreement as to what motive predominated, but in all cases in- cluded herein the US forces involved afforded some measure of protection to US nationals or their property. The cases are listed according to the date of the first use of US forces. A case is included only where there was an actual physical landing to protect nationals who were the subject of, or were threatened by, immediate or po- tential danger. Thus, for example, cases involving the landing of troops to punish past transgressions, or for the ostensible purpose of protecting na- tionals at some remote time in the future, have been omitted. While an ef- fort to isolate individual fact situations has been made, there are a good number of situations involving multiple landings closely related in time or context which, for the sake of convenience, have been treated herein as sin- gle episodes. The list of cases is based primarily upon the sources cited following this paragraph. -

AH199510.Pdf

... .-. Imagiq Cornbar A1 Magazine of the U.S. Navy corents October 1995, Number 942 < DT Jessica Farley (left), from San Diego, and DT Kassi Kosydar, from Anchorage, Alaska, both stationed at the Pearl Harbor Dental Clinic, get ready to examine an awaiting mouth.Photo by PHI Donald E Bray, NAVSUBTRACEN- PAC, Pearl Harbor. A During a break in the drydock activities of USS Dextrous (MCM 13), BM3 Stacey Reddig (left), of Ellinwood, Kan., explains how to stream minesweeping gear to FN Ryan Strietenberger, of Kingston, Ohio. Photo bySTG3 Troy Smlth, USS Dextrous (MCM 13). 4 AD2 Johnnie Brown, of Georgetown, S.C., schedules fleet airlifts in theOps Dept. of Navy Air Logistics Office, New Orleans. Photo byCDR Wililam G. Carnahan, Navy Air Logistics Office, New Orleans. Departments 2 Charthouse 43 Bearings 48 Shipmates Front Cover: Crew members ofUSS Buffalo (SSN 715) give the sub a complete make over in preparation for a ship's photo.Photo by PH1 Don Bray, NAVSUBTRACEN Pearl Harbor. Back Cover; USS George Washington (CVN 73) Sailors SN William McCoy, from Chicago (right), and BM3 Ryan Esser, from Port Charlotte, Fla., at work on the pier. Photo by PH1 Alexander C. Hicks, NAVPACENPAC, Norfolk. OCTOBER 1995 Charthouse housing areas, to provide information Type the file name and select a IRS says moving allow. to Navy members concerning limita- transfer protocol supported by your ance is non-taxable tions in both family and bachelor computer software. Finally, when you quarters in certain geographic areas. see the prompt, “waiting for start Members assigned to a permanent duty station (PDS) in CONUS where The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) housing is designated as critical, may has ruled that Temporary Lodging request a Variable Housing Allowance Allowance (TLA), Temporary Lodging based on the location of current Expense (TLE), Dislocation Allowance permanent residence of family mem- (DM) and Move-in Housing Allowance bers, rather than the location of the (MIHA) are permanently non-taxable. -

National Defense

National Defense of 32 code PARTS 700 TO 799 Revised as of July 1, 1999 CONTAINING A CODIFICATION OF DOCUMENTS OF GENERAL APPLICABILITY AND FUTURE EFFECT AS OF JULY 1, 1999 regulations With Ancillaries Published by the Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration as a Special Edition of the Federal Register federal VerDate 18<JUN>99 04:37 Jul 24, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8091 Sfmt 8091 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX 183121f PsN: 183121F 1 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1999 For sale by U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402±9328 VerDate 18<JUN>99 04:37 Jul 24, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 8092 Sfmt 8092 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX 183121f PsN: 183121F ?ii Table of Contents Page Explanation ................................................................................................ v Title 32: Subtitle AÐDepartment of Defense (Continued): Chapter VIÐDepartment of the Navy ............................................. 5 Finding Aids: Table of CFR Titles and Chapters ....................................................... 533 Alphabetical List of Agencies Appearing in the CFR ......................... 551 List of CFR Sections Affected ............................................................. 561 iii VerDate 18<JUN>99 00:01 Aug 13, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 8092 Sfmt 8092 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX pfrm04 PsN: 183121F Cite this Code: CFR To cite the regulations in this volume use title, part and section num- ber. Thus, 32 CFR 700.101 refers to title 32, part 700, section 101. iv VerDate 18<JUN>99 04:37 Jul 24, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 8092 Sfmt 8092 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX 183121f PsN: 183121F Explanation The Code of Federal Regulations is a codification of the general and permanent rules published in the Federal Register by the Executive departments and agen- cies of the Federal Government. -

32 CFR Ch. VI (7–1–10 Edition) § 706.2

§ 706.2 32 CFR Ch. VI (7–1–10 Edition) § 706.2 Certifications of the Secretary TABLE ONE—Continued of the Navy under Executive Order Distance in 11964 and 33 U.S.C. 1605. meters of The Secretary of the Navy hereby forward masthead finds and certifies that each vessel list- Vessel Number light below ed in this section is a naval vessel of minimum required special construction or purpose, and height. that, with respect to the position of § 2(a)(i) Annex I the navigational lights listed in this section, it is not possible to comply USS RODNEY M. DAVIS .............. FFG 60 1.6 fully with the requirements of the pro- USS INGRAHAM ........................... FFG 61 1.37 USS FREEDOM ............................ LCS 1 5.99 visions enumerated in the Inter- USS INDEPENDENCE .................. LCS 2 4.91 national Regulations for Preventing USS OGDEN ................................. LPD 5 4.15 Collisions at Sea, 1972, without inter- USS DULUTH ................................ LPD 6 4.4 USS DUBUQUE ............................ LPD 8 4.2 fering with the special function of the USS DENVER ............................... LPD 9 4.4 vessel. The Secretary of the Navy fur- USS JUNEAU ................................ LPD 10 4.27 ther finds and certifies that the naviga- USS NASHVILLE ........................... LPD 13 4.38 USS TRIPOLI ................................ LPH 10 3.3 tional lights in this section are in the LCAC (class) .................................. LCAC 1 1 6.51 closest possible compliance with the through applicable provisions of the Inter- LCAC 100 national Regulations for Preventing LCAC (class) .................................. LCAC 1 7.84 through (Temp.) 2 Collisions at Sea, 1972. LCAC 100 USS INCHON ................................ MCS 12 3.0 TABLE ONE NR–1 ............................................. -

US Navy Supply Corps

SEPTEMBER / OCTOBER 2017 SUPPOs Supplying the Fight A Message from the Chief of Supply Corps Recognizing the central importance of supply to establishing the Navy, President George Washington laid the foundation for the U.S. Navy Supply Corps in 1775 with the appointment of Tench Francis, a Philadelphia businessman, as the country’s first Purveyor of Public Supplies. Francis provided vital support to the first Navy ships, and started our tradition of selfless service. The Navy’s trusted providers of supplies, our supply officers (SUPPOs) keep operations running smoothly to support the mission. But they can’t do it alone. Working as a team with their skilled and experienced enlisted members, our SUPPOs are experts in our field who know inventory and financial management, food, retail, postal operations, and disbursing management. They are leaders and problem solvers who tackle complex challenges to implement effective and efficient management solutions, ensuring our customers’ needs are met. To be “Ready for Sea,” we must be professionally ready with the skills to operate in all our lines of operation. We also need character readiness, demonstrated by our integrity, accountabili- ty, initiative, and toughness. Lastly, we need to be individually ready; to be fit, healthy, and ready to meet the demands of the fight. This issue provides insights from our SUPPOs’ important work as they meet the unique needs of their various commands. Like the pursuers and paymasters who have gone before, SUPPOs uphold our rich heritage, and embrace their responsibilities to support the warfighter with a servant’s heart. Our SUPPO’s success depends on their character and competence, knowledge of the shore infrastructure, relationships with our professional civilian workforce, and on the enlisted members they lead and serve with. -

Department of the Navy, Dod § 706.2

Department of the Navy, DoD § 706.2 § 706.2 Certifications of the Secretary TABLE ONE—Continued of the Navy under Executive Order Distance in 11964 and 33 U.S.C. 1605. meters of The Secretary of the Navy hereby forward masthead finds and certifies that each vessel list- Vessel Number light below ed in this section is a naval vessel of minimum required special construction or purpose, and height. that, with respect to the position of § 2(a)(i) Annex I the navigational lights listed in this section, it is not possible to comply USS SAMUEL B. ROBERTS ........ FFG 58 1.6 fully with the requirements of the pro- USS KAUFFMAN ........................... FFG 59 1.6 USS RODNEY M. DAVIS .............. FFG 60 1.6 visions enumerated in the Inter- USS INGRAHAM ........................... FFG 61 1.37 national Regulations for Preventing USS FREEDOM ............................ LCS 1 5.99 Collisions at Sea, 1972, without inter- USS INDEPENDENCE .................. LCS 2 4.14 USS FORT WORTH ...................... LCS 3 5.965 fering with the special function of the USS CORONADO ......................... LCS 4 4.20 vessel. The Secretary of the Navy fur- USS MILWAUKEE ......................... LCS 5 6.75 ther finds and certifies that the naviga- USS JACKSON ............................. LCS 6 4.91 USS DETROIT ............................... LCS 7 6.80 tional lights in this section are in the USS MONTGOMERY .................... LCS 8 4.91 closest possible compliance with the USS LITTLE ROCK ....................... LCS 9 6.0 applicable provisions of the Inter- USS GABRIELLE GIFFORDS ....... LCS 10 4.91 national Regulations for Preventing USS SIOUX CITY .......................... LCS 11 5.98 USS OMAHA ................................. LCS 12 4.27 Collisions at Sea, 1972. -

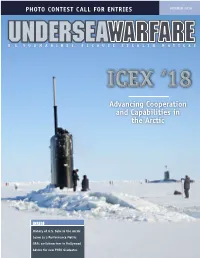

Advancing Cooperation and Capabilities in the Arctic

PHOTO CONTEST CALL FOR ENTRIES SUMMER 2018 U. S. SUBMARINES … B ECAUSE STEALTH MATTERS ICEX ‘18 Advancing Cooperation and Capabilities in the Arctic INSIDE History of U.S. Subs in the Arctic Leave as a Performance Metric Q&A: ex-Submariner in Hollywood Advice for new PNEO Graduates U. S. SUBMARINES … B ECAUSE STEALTH MATTERS THE OFFiciaL MAGAZINE OF THE U.S. SUBMARINE Force FORCE COMMANDER’S CORNER ICEX ‘18 Vice Adm. Joseph E. Tofalo, USN Commander, Submarine Forces Summer 2018 4 Advancing Cooperation and 65 Capabilities in the Arctic o. N Arctic Exercises ssue I 4 by Lt. Courtney Callaghan, CSS-11 PAO, Mr. Theo Goda, Joseph Hardy and Larry Estrada, Arctic Submarine Lab Undersea Warriors, Sixty Years of U.S. Submarines in the Arctic 8 by Lt. Cmdr. Bradley Boyd, Officer in Charge, Historic Ship Nautilus As my three-year tenure as Commander, Submarine Forces draws to a close, I want you all to know that it has been Director, Submarine Force Museum the greatest privilege of my career to be your Force Commander. It has been an honor to work with the best people on the best warships supported by the best families! 8 10 Operation Sunshine For much of the last century, we really only had one main competitor on which to focus. We are now in a world by Lt. Cmdr. Bradley Boyd, Officer in Charge, Historic Ship Nautilus where we not only have two near-peer competitors with which to contend, but also three non-near-peer adversaries Director, Submarine Force Museum that challenge us as well—overall a much broader field. -

CONFIDENTIAL - Unclassified Upon Removal of Enclosure (1)

r.nNEI D~NTIAJ '-~<~ 1 1 ~ ··~~Ct:.~~ Q~RTMENT OF THE NAVY COMMANDER SUBMARINE FORCE UNITED STATES PACIFIC FLEET PEARL HARBOR, HI 96860-6550 5760 Ser 002P/C 00340 09 JUN 1992 . CONFIDENTIAL - Unclassified upon removal of enclosure (1) From: Commander Submarine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet To: Director of Naval History (OP-09B9) Subj: COMMAND HISTORY FOR 1991 (OPNAV Report 5750-1) Ref: (a) OPNAVINST 5750.12C Encl: (1) 1991 COMSUBPAC Command History (U) (2) Biography and photograph of RADM Henry C. McKinney, USN (COMSUBPAC) r 8>" ;.; :..L~ ;,., ,6 f J p' L r lP't' : ..... ., -i-,.:.", ;,'5-, -/''; .~-(- 1. Enclosure (1) is forwarded in accorda c ith reference (a). By direction Copy to: CINCPACFLT CONFIDENTIAL ,. 1~~'" HiSTORICAL CENTER CONFIDENTIAL ·E.O.l~~'S~gnatu. ..e ~bt ADMINISTRATION AND PERSONNEL Date ~ . - 1.-. (U) MISSION. The Commander of the Submarine Force U.S. Pacific Fleet is the principal advisor to the Fleet Commander in Chief for submarine matters. Under his command are 45 submarines. The Submarine Force also includes 3 submarine tenders, 3 floating dry docks, 2 submarine rescue ships, and 4 deep submergence vehicles, 9 submarine groups/squadrons and 3 bases. There are 1,436 officers, 16,048 enlisted personnel and 1,857 civilians in the command. 2. (U) PUBLIC AfFAIRS. a. (U) In 1991, the staff Public Affairs Office arranged 79 tours for approximately 1,028 people. This included 17 day-long embarkations for 153 distinguished visitors. Additional items of note include: USS LOUISVILLE (SSN 724) launched the first submarine-based TOMAHAWK missile on 19 Jan 91 in support of Operation Desert Storm. -

Program Edit Smaller

PB 1 ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM SPONSORS DIAMOND General Dynamics Electric Boat Lockheed Martin Newport News Shipbuilding a Division of Huntington Ingalls Industries PLATINUM General Dynamics Mission Systems L3Harris Technologies Northrop Grumman Raytheon Technologies GOLD BWX Technologies Leonardo DRS Teledyne Brown SILVER Carahsoft HDR Oceaneering International Sheffield Forgemasters Sonalysts Systems Planning and Analysis The Boeing Company VACCO 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS MONDAY AGENDA ......................................................................................................................................................5 TUESDAY AGENDA .....................................................................................................................................................6 WEDNESDAY AGENDA ................................................................................................................................................7 SPEAKERS RDML Edward Anderson, USN .................................................................................................................................................................. 9 FORCM(SS) Steve Bosco, USN ................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Hon. Kenneth Braithwaite ...................................................................................................................................................................... 10 ADM Frank Caldwell, -

Sept 2017 Newsletter

Volume 70 Number 5 Our September 12th Luncheon Speaker September, 2017 Commanding Officer, USS John C. Stennis Community Afliates CVN-74 Capt Gregory Huffman AMI International Evergreen Mayflower The son of a career First Command Financial Planning naval officer, Capt. Greg General Dynamics NASSCO Huffman is a 1989 Kitsap Bank graduate of the United Navy Federal Credit Union States Naval Academy. Navy Museums NW He earned a Master of Olympic College Foundation Arts in History from the Our Place Pub and Eatery University of Maryland in Pacific NW Defense Coalition 1989 and a Master of Science in Aviation Raytheon Integrated Defense Systems Systems from the Suquamish Clearwater Casino University of Tennessee Wells Fargo Advisors Financial Network in 2000. Sea duty flying assignments include a junior officer New Members tour with the 'Rampagers' of Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 83 based in Cecil Field, Fla., a Traci Kokkeler Pamela Hurst- department head tour with the 'Sunliners' of Joseph Smith Chalupka VFA-81, based in Oceana, Va., and command of David Sorin Jorge Nolasco the VFA-27 'Royal Maces' based in Atsugi, Japan. Simon Feldman David Gross (R) He completed multiple deployments aboard USS Natalie Murphy Kirk Piering (R) Saratoga (CV 60), USS Enterprise (CVN 65), USS Loyd Cockerham Mark Tomas (R) Kitty Hawk (CV 63) and USS George Washington Sally George Jon Berglind (R) (CVN 73), and flew combat missions over Bosnia, Samuel White (R) - Returning Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan. Capt. Huffman was Gabriel Rees CA Members named the Strike Fighter Wing Atlantic F/A-18 Pilot of the Year for 1996 and won the Mike Longardt Leadership Award in 2001.