Supplemental Information Vesicular Glutamate Transporters Use Flexible Anion and Cation Binding Sites for Efficient Accumulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Published Version

Cell Reports Article Dual and Direction-Selective Mechanisms of Phosphate Transport by the Vesicular Glutamate Transporter Julia Preobraschenski,1 Cyril Cheret,2 Marcelo Ganzella,1 Johannes Friedrich Zander,2 Karin Richter,2 Stephan Schenck,3 Reinhard Jahn,1,4,* and Gudrun Ahnert-Hilger2,* 1Department of Neurobiology, Max-Planck-Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, 37077 Go¨ ttingen, Germany 2Institute for Integrative Neuroanatomy, Charite´ , Medical University of Berlin, 10115 Berlin, Germany 3Laboratory of Biomolecular Research, Paul Scherrer Institut, CH-5232 Villigen, Switzerland 4Lead Contact *Correspondence: [email protected] (R.J.), [email protected] (G.A.-H.) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.055 SUMMARY ities and transport mechanisms vary among the subfamilies, because the transmitters have different net charges, thus Vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUTs) fill synap- requiring distinct ion-coupling mechanisms (Omote et al., tic vesicles with glutamate and are thus essential for 2011). Moreover, the transporters must maintain efficient uptake glutamatergic neurotransmission. However, VGLUTs not only when a vesicle is empty, i.e., filled with extracellular were originally discovered as members of a trans- electrolytes acquired during endocytosis, but also when a porter subfamily specific for inorganic phosphate vesicle is partially filled, with transmitter concentrations well (P ). It is still unclear how VGLUTs accommodate exceeding 100 mM requiring highly adaptive transport mecha- i nisms (Farsi et al., 2017)(Takamori, 2016). glutamate transport coupled to an electrochemical + The ionic mechanism or mechanisms by which SVs are filled proton gradient DmH with inversely directed Pi + with glutamate, the main excitatory neurotransmitter of the transport coupled to the Na gradient and the mem- mammalian CNS, are only partially understood. -

Protein Kinase C Activates an H' (Equivalent) Conductance in The

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 88, pp. 10816-10820, December 1991 Cell Biology Protein kinase C activates an H' (equivalent) conductance in the plasma membrane of human neutrophils (HI channels/pH regulation/leukocytes/H+-ATPase/bafllomycin) ARVIND NANDA AND SERGIO GRINSTEIN* Division of Cell Biology, Hospital for Sick Children, 555 University Avenue, Toronto, ON M5G 1X8, Canada Communicated by Edward A. Adelberg, August 12, 1991 ABSTRACT The rate of metabolic acid generation by it can be calculated that pH1 would be expected to drop by neutrophils increases greatly when they are activated. Intra- over 5 units (to pH 1.6) if the metabolically generated H+ cellular acidification is prevented in part by Na+/H' ex- were to remain within the cell. However, cells stimulated in change, but a sizable component ofH+ extrusion persists in the the nominal absence of Na+ and HCO- maintain their pH1 nominal absence of Na' and HCO3 . In this report we deter- above 6.4, suggesting that alternative (Na+- and HCO3- mined the contribution to H+ extrusion of a putative HI independent) H+ extrusion mechanisms must exist in acti- conductive pathway and its mode ofactivation. In unstimulated vated neutrophils. Accordingly, accelerated extracellular cells, H+ conductance was found to be low and unaffected by acidification can be recorded under these conditions. depolarization. An experimental system was designed to min- The existence of H+-conducting channels has been docu- imize the metabolic acid generation and membrane potential mented in snail neurones (5) and axolotl oocytes (6). In these changes associated with neutrophil activation. By using this tissues, the channels are inactive at the resting plasma system, (3-phorbol esters were shown to increase the H+ membrane potential (Em) but open when the membrane (equivalent) permeability of the plasma membrane. -

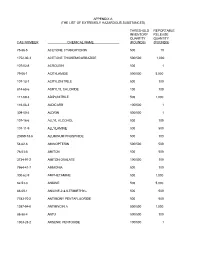

The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances)

APPENDIX A (THE LIST OF EXTREMELY HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES) THRESHOLD REPORTABLE INVENTORY RELEASE QUANTITY QUANTITY CAS NUMBER CHEMICAL NAME (POUNDS) (POUNDS) 75-86-5 ACETONE CYANOHYDRIN 500 10 1752-30-3 ACETONE THIOSEMICARBAZIDE 500/500 1,000 107-02-8 ACROLEIN 500 1 79-06-1 ACRYLAMIDE 500/500 5,000 107-13-1 ACRYLONITRILE 500 100 814-68-6 ACRYLYL CHLORIDE 100 100 111-69-3 ADIPONITRILE 500 1,000 116-06-3 ALDICARB 100/500 1 309-00-2 ALDRIN 500/500 1 107-18-6 ALLYL ALCOHOL 500 100 107-11-9 ALLYLAMINE 500 500 20859-73-8 ALUMINUM PHOSPHIDE 500 100 54-62-6 AMINOPTERIN 500/500 500 78-53-5 AMITON 500 500 3734-97-2 AMITON OXALATE 100/500 100 7664-41-7 AMMONIA 500 100 300-62-9 AMPHETAMINE 500 1,000 62-53-3 ANILINE 500 5,000 88-05-1 ANILINE,2,4,6-TRIMETHYL- 500 500 7783-70-2 ANTIMONY PENTAFLUORIDE 500 500 1397-94-0 ANTIMYCIN A 500/500 1,000 86-88-4 ANTU 500/500 100 1303-28-2 ARSENIC PENTOXIDE 100/500 1 THRESHOLD REPORTABLE INVENTORY RELEASE QUANTITY QUANTITY CAS NUMBER CHEMICAL NAME (POUNDS) (POUNDS) 1327-53-3 ARSENOUS OXIDE 100/500 1 7784-34-1 ARSENOUS TRICHLORIDE 500 1 7784-42-1 ARSINE 100 100 2642-71-9 AZINPHOS-ETHYL 100/500 100 86-50-0 AZINPHOS-METHYL 10/500 1 98-87-3 BENZAL CHLORIDE 500 5,000 98-16-8 BENZENAMINE, 3-(TRIFLUOROMETHYL)- 500 500 100-14-1 BENZENE, 1-(CHLOROMETHYL)-4-NITRO- 500/500 500 98-05-5 BENZENEARSONIC ACID 10/500 10 3615-21-2 BENZIMIDAZOLE, 4,5-DICHLORO-2-(TRI- 500/500 500 FLUOROMETHYL)- 98-07-7 BENZOTRICHLORIDE 100 10 100-44-7 BENZYL CHLORIDE 500 100 140-29-4 BENZYL CYANIDE 500 500 15271-41-7 BICYCLO[2.2.1]HEPTANE-2-CARBONITRILE,5- -

Relationship Between Cell Morphology and Intracellular Potassium Concentration in Candida Albicans Hiroshi Watanabe, Masayuki Azuma, Koichi Igarashi, Hiroshi Ooshima

J. Antibiot. 59(5): 281–287, 2006 THE JOURNAL OF ORIGINAL ARTICLE ANTIBIOTICS Relationship between Cell Morphology and Intracellular Potassium Concentration in Candida albicans Hiroshi Watanabe, Masayuki Azuma, Koichi Igarashi, Hiroshi Ooshima Received: February 15, 2006 / Accepted: May 10, 2006 © Japan Antibiotics Research Association Abstract Previously we reported that valinomycin [1]. It is thought that this ability is related to pathogenicity, inhibited hyphal growth and induced growth as a chain which is reduced by the inhibition of hyphal growth, of yeast cells under hyphal growth induction conditions because morphological mutants defective in hyphal growth in Candida albicans. To elucidate the hyphal growth exhibit low virulence compared to the parental strain [2]. inhibition by valinomycin, we examined the effect of Understanding the dimorphism and screening for hyphal various chemicals on the morphology and found that growth inhibitors should lead to the development of new miconazole inhibited hyphal growth as well as valinomycin: antifungal therapies. both compounds promoted the leakage of potassium from In a previous report, we described that valinomycin cells. Analysis of intracellular potassium suggested that inhibited hyphal growth and induced growth as a chain of hyphal cells contain potassium at high concentrations in yeast cells under hyphal growth induction conditions in C. comparison with yeast cells. Hyphal growth inhibition by albicans [3]. Valinomycin, a potassium ionophore, is known valinomycin was obstructed by the addition of serum. as an antibiotic against tubercle bacillus, but its effect on Potassium measurement showed that the addition of serum the morphology of yeast and fungus is not well known. We causes an increase in intracellular potassium, suggesting also showed that valinomycin inhibited hyphal growth in C. -

Optogenetic Visualization of Presynaptic Tonic Inhibition of Cerebellar Parallel Fibers

Optogenetic Visualization of Presynaptic Tonic Inhibition of Cerebellar Parallel Fibers The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Berglund, K. et al. “Optogenetic Visualization of Presynaptic Tonic Inhibition of Cerebellar Parallel Fibers.” Journal of Neuroscience 36, 21 (May 2016): 5709–5723 © 2016 The Author(s) As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4366-15.2016 Publisher Society for Neuroscience Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/112258 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ The Journal of Neuroscience, May 25, 2016 • 36(21):5709–5723 • 5709 Cellular/Molecular Optogenetic Visualization of Presynaptic Tonic Inhibition of Cerebellar Parallel Fibers X Ken Berglund,1,2* Lei Wen,3,4,5* Robert L. Dunbar,1 Guoping Feng,1 and XGeorge J. Augustine3,4,5,6 1Department of Neurobiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27710, 2Departments of Neurosurgery and Anesthesiology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia 30322, 3Center for Functional Connectomics, Korea Institute of Science and Technology, Seoul 136-791, Republic of Korea, 4Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Research Techno Plaza, Singapore 637553 Singapore, 5Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore 138673, Singapore, and 6MBL, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543 Tonic inhibition was imaged in cerebellar granule cells of transgenic mice expressing the optogenetic chloride indicator, Clomeleon. Blockade of GABAA receptors substantially reduced chloride concentration in granule cells due to block of tonic inhibition. This indicates thattonicinhibitionisasignificantcontributortotherestingchlorideconcentrationofthesecells.Tonicinhibitionwasobservednotonly in granule cell bodies, but also in their axons, the parallel fibers (PFs). -

Role of an Electrical Potential in the Coupling of Metabolic Energy To

Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 70, No. 6, pp. 1804-1808, June 1973 Role of an Electrical Potential in the Coupling of Metabolic Energy to Active Transport by Membrane Vesicles of Escherichia coli (chemiosmotic hypothesis/lipid-soluble ions/valinomycin/ionophores/amino-acid transport) HAJIME HIRATA, KARLHEINZ ALTENDORF, AND FRANKLIN M. HAROLD* Division of Research, National Jewish Hospital and Research Center, Denver, Colorado 80206; and Department of Microbiology, University of Colorado Medical Center, Denver, Colorado 80220 Communicated by Saul Roseman, April 12, 1973 ABSTRACT Membrane vesicles from E. coli can oxidize probably occurs quite directly at the level of the membrane D-lactate and other substrates and couple respiration to its the active transport of sugars and amino acidl8. The pres- and constituent proteins (5-7). Kaback and Barnes (8) ent experiments bear on the nature of the link between proposed a tentative mechanism by which the coupling might respiration and transport. be effected: the transport carriers are thought to monitor Respiring vesicles were found to accumulate dibenzyl- the redox state of the electron-transport chain and themselves dimethylammonium ion, a synthetic lipid-soluble cation undergo cyclic oxidation and reduction of critical sulfhydryl that serves as an indicator of an electrical potential. The results suggest that oxidation of it-lactate generates groups; each cycle is accompanied by concurrent changes in a membrane potential, vesicle interior negative, of the the orientation of the carrier center and in its affinity for the order of -100 mV. In vesicles lacking substrate, an electri- substrate, leading to accumulation of the substrate in the cal potential was created by induction of electrogenic lumen of the vesicle. -

Contribution of Particle-Induced Lysosomal Membrane Hyperpolarization to Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Contribution of Particle-Induced Lysosomal Membrane Hyperpolarization to Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization Tahereh Ziglari 1 , Zifan Wang 2 and Andrij Holian 1,* 1 Department of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Center for Environmental Health Sciences, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812, USA; [email protected] 2 Division of Chemistry and Biochemistry, College of Humanities and Sciences, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-406-243-4018 Abstract: Lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) has been proposed to precede nanoparticle- induced macrophage injury and NLRP3 inflammasome activation; however, the underlying mecha- nism(s) of LMP is unknown. We propose that nanoparticle-induced lysosomal hyperpolarization triggers LMP. In this study, a rapid non-invasive method was used to measure changes in lysosomal membrane potential of murine alveolar macrophages (AM) in response to a series of nanoparticles (ZnO, TiO2, and CeO2). Crystalline SiO2 (micron-sized) was used as a positive control. Changes in cytosolic potassium were measured using Asante potassium green 2. The results demonstrated that ZnO or SiO2 hyperpolarized the lysosomal membrane and decreased cytosolic potassium, suggesting increased lysosome permeability to potassium. Time-course experiments revealed that lysosomal hyperpolarization was an early event leading to LMP, NLRP3 activation, and cell death. In contrast, TiO2- or valinomycin-treated AM did not cause LMP unless high doses led to lysosomal hyperpolar- Citation: Ziglari, T.; Wang, Z.; ization. Neither lysosomal hyperpolarization nor LMP was observed in CeO2-treated AM. These Holian, A. Contribution of results suggested that a threshold of lysosomal membrane potential must be exceeded to cause Particle-Induced Lysosomal LMP. -

![Gradient Effects in Electrically Neutral [Na + K + 2C1] Co-Transport](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3987/gradient-effects-in-electrically-neutral-na-k-2c1-co-transport-1073987.webp)

Gradient Effects in Electrically Neutral [Na + K + 2C1] Co-Transport

Catecholamine-stimulated Ion Transport in Duck Red Cells Gradient Effects in Electrically Neutral [Na + K + 2C1] Co-Transport MARK HAAS, WILLIAM F . SCHMIDT III, and THOMAS J . MCMANUS From the Department of Physiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27710 ABSTRACT The transient increase in cation permeability observed in duck red cells incubated with norepinephrine has been shown to be a linked, bidirectional, co-transport of sodium plus potassium . This pathway, sensitive to loop diuretics such as furosemide, was found to have a [Na + K] stoichiometry of 1 :1 under all conditions tested . Net sodium efflux was inhibited by increasing external potassium, and net potassium efflux was inhibited by increasing external sodium . Thus, the movement of either cation is coupled to, and can be driven by, the gradient of its co-ion . There is no evidence of trans stimulation of co- transport by either cation . The system also has a specific anion requirement satisfied only by chloride or bromide . Shifting the membrane potential by varying either external chloride (at constant internal chloride) or external potassium (at constant internal potassium in the presence of valinomycin and DIDS [4,4'-diisothiocyano-2,2'-disulfonic acid stilbene]), has no effect on nor- epinephrine-stimulated net sodium transport . Thus, this co-transport system is unaffected by membrane potential and is therefore electrically neutral . Finally, under the latter conditions-when E,n was held constant near Ex and chloride was not at equilibrium-net sodium extrusion against a substantial electrochem- ical gradient could be produced by lowering external chloride at high internal concentrations, thereby demonstrating that the anion gradient can also drive co-transport . -

Active Transport of Y-Aminobutyric Acid and Glycine Into Synaptic Vesicles (Neurotransmitter/Mg-Activating Atpase/Proton Gradient/Brain/Spinal Cord) PHILLIP E

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 86, pp. 3877-3881, May 1989 Neurobiology Active transport of y-aminobutyric acid and glycine into synaptic vesicles (neurotransmitter/Mg-activating ATPase/proton gradient/brain/spinal cord) PHILLIP E. KISH*, CAROLYN FISCHER-BOVENKERK*, AND TETSUFUMI UEDA*tt§ *Mental Health Research Institute and Departments of tPharmacology and Psychiatry, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Communicated by Philip Siekevitz, January 3, 1989 ABSTRACT Although y-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and also accumulated into synaptic vesicles in an ATP-dependent glycine are recognized as major amino acid inhibitory neuro- manner and that their uptake is driven by an electrochemical transmitters in the central nervous system, their storage is proton gradient. We have characterized these uptake systems poorly understood. In this study we have characterized vesic- with respect to sensitivity to chloride and the specificity of ular GABA and glycine uptakes in the cerebrum and spinal the transporter. Preliminary accounts of this work have been cord, respectively. We present evidence that GABA and glycine reported in abstract form (14, 15). are each taken up into isolated synaptic vesicles in an ATP- dependent manner and that the uptake is driven by an electrochemical proton gradient. Uptake for both amino acids EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES exhibited kinetics with low affinity (Km in the millimolar range) Materials. All GABA and glycine analogs were from Sigma similar to vesicular glutamate uptake. The ATP-dependent or Aldrich. 4-Amino-n-[2,3-3H]butyric acid (50 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci GABA uptake was not inhibited by the putative amino acid = 37 GBq), [2-3H]glycine (19 Ci/mmol), and other tritiated neurotransmitters glycine, taurine, glutamate, or aspartate or amino acids tested for uptake were obtained from Amersham. -

Xanthan Gum Derivatives: Review of Synthesis, Properties and Diverse Applications Cite This: RSC Adv., 2020, 10,27103 Jwala Patel,A Biswajit Maji,B N

RSC Advances View Article Online REVIEW View Journal | View Issue Xanthan gum derivatives: review of synthesis, properties and diverse applications Cite this: RSC Adv., 2020, 10,27103 Jwala Patel,a Biswajit Maji,b N. S. Hari Narayana Moorthya and Sabyasachi Maiti *a Natural polysaccharides are well known for their biocompatibility, non-toxicity and biodegradability. These properties are also inherent to xanthan gum (XG), a microbial polysaccharide. This biomaterial has been extensively investigated as matrices for tablets, nanoparticles, microparticles, hydrogels, buccal/ transdermal patches, tissue engineering scaffolds with different degrees of success. However, the native XG has its own limitations with regards to its susceptibility to microbial contamination, unusable viscosity, poor thermal and mechanical stability, and inadequate water solubility. Chemical modification can circumvent these limitations and tailor the properties of virgin XG to fulfill the unmet needs of drug delivery, tissue engineering, oil drilling and other applications. This review illustrates the process of chemical modification and/crosslinking of XG via etherification, esterification, acetalation, amidation, and Received 16th May 2020 oxidation. This review further describes the tailor-made properties of novel XG derivatives and their Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. Accepted 13th July 2020 potential application in diverse fields. The physicomechanical modification and its impact on the DOI: 10.1039/d0ra04366d properties of XG are also discussed. Overall, the recent developments on XG derivatives are very rsc.li/rsc-advances promising to progress further with polysaccharide research. 1. Introduction a polyanionic character. Chemical structure of XG is illustrated in Fig. 1a and b. Polysaccharides are isolated from renewable sources and have The hydroxy and carboxy polar groups of XG reconnoiter nontoxic, biocompatible, biodegradable, and bioadhesive intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonding interac- This article is licensed under a 6 properties. -

List of Extremely Hazardous Substances

Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Facility Reporting Compliance Manual List of Extremely Hazardous Substances Threshold Threshold Quantity (TQ) Reportable Planning (pounds) Quantity Quantity (Industry Use (pounds) (pounds) CAS # Chemical Name Only) (Spill/Release) (LEPC Use Only) 75-86-5 Acetone Cyanohydrin 500 10 1,000 1752-30-3 Acetone Thiosemicarbazide 500/500 1,000 1,000/10,000 107-02-8 Acrolein 500 1 500 79-06-1 Acrylamide 500/500 5,000 1,000/10,000 107-13-1 Acrylonitrile 500 100 10,000 814-68-6 Acrylyl Chloride 100 100 100 111-69-3 Adiponitrile 500 1,000 1,000 116-06-3 Aldicarb 100/500 1 100/10,000 309-00-2 Aldrin 500/500 1 500/10,000 107-18-6 Allyl Alcohol 500 100 1,000 107-11-9 Allylamine 500 500 500 20859-73-8 Aluminum Phosphide 500 100 500 54-62-6 Aminopterin 500/500 500 500/10,000 78-53-5 Amiton 500 500 500 3734-97-2 Amiton Oxalate 100/500 100 100/10,000 7664-41-7 Ammonia 500 100 500 300-62-9 Amphetamine 500 1,000 1,000 62-53-3 Aniline 500 5,000 1,000 88-05-1 Aniline, 2,4,6-trimethyl- 500 500 500 7783-70-2 Antimony pentafluoride 500 500 500 1397-94-0 Antimycin A 500/500 1,000 1,000/10,000 86-88-4 ANTU 500/500 100 500/10,000 1303-28-2 Arsenic pentoxide 100/500 1 100/10,000 1327-53-3 Arsenous oxide 100/500 1 100/10,000 7784-34-1 Arsenous trichloride 500 1 500 7784-42-1 Arsine 100 100 100 2642-71-9 Azinphos-Ethyl 100/500 100 100/10,000 86-50-0 Azinphos-Methyl 10/500 1 10/10,000 98-87-3 Benzal Chloride 500 5,000 500 98-16-8 Benzenamine, 3-(trifluoromethyl)- 500 500 500 100-14-1 Benzene, 1-(chloromethyl)-4-nitro- 500/500 -

The Role of Ion Channels and Intracellular Metal Ions in Apoptosis of Xenopus Oocytes

Linköping University Medical Dissertation № 1424 The role of ion channels and intracellular metal ions in apoptosis of Xenopus oocytes Ulrika Englund Division of Cell Biology Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine Faculty of Health Sciences, Linköping University, Sweden Linköping 2014 Ulrika Englund, 2014 Linköping University, Sweden. Cover: Magnified Xenopus laevis oocytes injected in the nucleus with red dye (left) and uninjected (right). Photo by Ulrika Englund. Published articles have been reprinted with the permission of the respective copyright holders. Printed in Sweden by LiU‐Tryck, Linköping, Sweden, 2014. ISBN 978‐91‐7519‐220‐8 ISSN 0345‐0082 INFALL (ur Barfotabarn,1933) ”Man dansar däruppe ‐ klarvaket är huset fast klockan är tolv. Då slår det mig plötsligt att taket, mitt tak, är en annans golv.” ‐Nils Ferlin Table of contents Table of contents LIST OF PAPERS ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 APOPTOSIS ............................................................................................................................................................