Effect of Architectural Styles on Objective Acoustical Measures in Portuguese Catholic Churches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barcelona and the Paradox of the Baroque by Jorge Luis Marzo1

Barcelona and the Paradox of the Baroque By Jorge Luis Marzo1 Translation by Mara Goldwyn Catalan historiography constructed, even from its very beginnings, the idea that Catalunya was not Baroque; that is, Baroque is something not very "proper" to Catalunya. The 17th and 18th centuries represent the dark Baroque age, in contrast with a magnificent Medieval and Renaissance era, during which the kingdom of Catalunya and Aragón played an important international role in a large part of the Mediterranean. The interpretation suggests that Catalunya was Baroque despite itself; a reading that, from the 19th century on - when it is decided that all negative content about Baroque should be struck from the record in order to transform it into a consciously commercial and urban logo - makes implicit that any reflection on such content or Baroque itself will be schizophrenic and paradoxical. Right up to this day. Though the (always Late-) Baroque style was present in buildings, embellishments and paintings, it however did not have an official environment in which to expand and legitimate itself, nor urban spaces in which to extend its setup (although in Tortosa, Girona, and other cities there were important Baroque features). The Baroque style was especially evident in rural churches, but as a result of the occupation of principle Catalan plazas - particularly by the Bourbon crown of Castile - principal architectonic realizations were castles and military forts, like the castle of Montjuic or the military Citadel in Barcelona. Public Baroque buildings hardly existed: The Gothic ones were already present and there was little necessity for new ones. At the same time, there was more money in the private sphere than in the public for building, so Baroque programs were more subject to family representation than to the strictly political. -

2008 Romanesque in the Sousa Valley.Pdf

ROMANESQUE IN THE SOUSA VALLEY ATLANTIC OCEAN Porto Sousa Valley PORTUGAL Lisbon S PA I N AFRICA FRANCE I TA LY MEDITERRANEAN SEA Index 13 Prefaces 31 Abbreviations 33 Chapter I – The Romanesque Architecture and the Scenery 35 Romanesque Architecture 39 The Romanesque in Portugal 45 The Romanesque in the Sousa Valley 53 Dynamics of the Artistic Heritage in the Modern Period 62 Territory and Landscape in the Sousa Valley in the 19th and 20th centuries 69 Chapter II – The Monuments of the Route of the Romanesque of the Sousa Valley 71 Church of Saint Peter of Abragão 73 1. The church in the Middle Ages 77 2. The church in the Modern Period 77 2.1. Architecture and space distribution 79 2.2. Gilding and painting 81 3. Restoration and conservation 83 Chronology 85 Church of Saint Mary of Airães 87 1. The church in the Middle Ages 91 2. The church in the Modern Period 95 3. Conservation and requalification 95 Chronology 97 Castle Tower of Aguiar de Sousa 103 Chronology 105 Church of the Savior of Aveleda 107 1. The church in the Middle Ages 111 2. The church in the Modern Period 112 2.1. Renovation in the 17th-18th centuries 115 2.2. Ceiling painting and the iconographic program 119 3. Restoration and conservation 119 Chronology 121 Vilela Bridge and Espindo Bridge 127 Church of Saint Genes of Boelhe 129 1. The church in the Middle Ages 134 2. The church in the Modern Period 138 3. Restoration and conservation 139 Chronology 141 Church of the Savior of Cabeça Santa 143 1. -

Circle Patterns in Gothic Architecture

Bridges 2012: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Circle patterns in Gothic architecture Tiffany C. Inglis and Craig S. Kaplan David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science University of Waterloo [email protected] Abstract Inspired by Gothic-influenced architectural styles, we analyze some of the circle patterns found in rose windows and semi-circular arches. We introduce a recursive circular ring structure that can be represented using a set-like notation, and determine which structures satisfy a set of tangency requirements. To fill in the gaps between tangent circles, we add Appollonian circles to each triplet of pairwise tangent circles. These ring structures provide the underlying structure for many designs, including rose windows, Celtic knots and spirals, and Islamic star patterns. 1 Introduction Gothic architecture, a style of architecture seen in many great cathedrals and castles, developed in France in the late medieval period [1, 3]. This majestic style is often applied to ecclesiastical buildings to emphasize their grandeur and solemnity. Two key features of Gothic architecture are height and light. Gothic buildings are usually taller than they are wide, and the verticality is further emphasized through towers, pointed arches, and columns. In cathedrals, the walls are often lined with large stained glass windows to introduce light and colour into the buildings. In the mid-18th century, an architectural movement known as Gothic Revival began in England and quickly spread throughout Europe. The Neo-Manueline, or Portuguese Final Gothic, developed under the influence of traditional Gothic architecture and the Spanish Plateresque style [10]. The Palace Hotel of Bussaco, designed by Italian architect Luigi Manini and built between 1888 and 1907, is a well-known example of Neo-Manueline architecture (Figure 2). -

Timeline / 1850 to After 1930 / CITIES and URBAN SPACES

Timeline / 1850 to After 1930 / CITIES AND URBAN SPACES Date Country Theme 1852 - 1870 France Cities And Urban Spaces Georges Haussmann’s works in Paris cover all areas of city planning: streets and boulevards, reconstruction of buildings, parks and street furniture, drainage networks and water supply facilities, equipment and monuments. 1853 Lebanon Cities And Urban Spaces Antun Bey Najjar, a merchant who made his fortune in Constantinople, builds Khan Antun Bey in 1853. It becomes a great business centre and the building is used by many institutions such as Beirut’s foreign consulates, the Ottoman administration, postal services, merchants’ offices and Beirut’s first bank, Imperial Ottoman. 1854 - 1870 France Cities And Urban Spaces Construction of workers’ housing includes the utopian city of Familistère de Guise in Aisne (also called the “Social Palace”), set up by Jean-Baptiste André Godin between 1859 and 1870. 1855 Lebanon Cities And Urban Spaces A school is built by the Jesuits in Ghazir (Kisruwan district). 1856 Turkey Cities And Urban Spaces Fire in Aksaray district, #stanbul, destroys more than 650 buildings and is a major turning point in the history of #stanbul’s urban form. Italian architect Luigi Storari is appointed to carry out the re-building of the area, which is to conform to the new pattern: hence it is to be regular with straight and wide streets. 1856 Turkey Cities And Urban Spaces #stimlak Nizamnamesi (Regulation for Expropriation) issued. 1856 - 1860 Spain Cities And Urban Spaces Ildefonso Cerdá designs the "extension" of Barcelona in 1859. The orthogonal design of the streets creates a new neighbourhood: El Ensanche/L’Eixample. -

For As Low As Us$ 2399 Per Person

FOR AS LOW AS US$ 2,399 PER PERSON With Airline Tax Blocking Dates: June 23, July 21, Aug. 11, Sept. 15, Oct. 20, Nov. 17, Dec. 22, 2019 ITINERARY: Day 04: MALAGA - SEVILLE (B) Day 06: LISBON – TOLEDO – MADRID (B) we go northbound to the largest city of the autonomous We will back to Madrid via Toledo, a World Heritage Day 01: Arrived Barcelona community of Andalusia, Seville. This city was the capi- Site declared by UNESCO in 1986 for its extensive Arrive in Barcelona Airport, transfer to your hotel. tal of the Muslim dynasty, considered to be the guardian cultural and monumental heritage. This old city is lo- angel of culture in Andalusia and the birthplace of the cated on a mountaintop, surrounded on three sides by Day 02: BARCELONA - flamenco dance. Seville is the primary setting of many a bend in the Tagus River, and contains many histori- operas, the best known of which is Bizet’s Carmen. As cal sites. By strolling across the city, overlooking the VALENCLA - ALICANTE (B) the fourth largest city in Spain, it has hosted the World’s Alcázar of Toledo and visiting the grand structure of After breakfast, leave Barcelona for Spain’s third Fair in 1992. After visit Seville Cathedral, the largest Toledo Cathedral, you will feel the bustling of Spain in largest city, Valencia. Valencia’s history has Gothic cathedral and the third-largest church in the the old time. Then take a well-earned rest as you sit celebrated as the gateway to the Mediterranean. world. Its completion was back to the early 16th century back, catch a breath taking landscape of Spain and It’s commercially and culturally rich, with Moorish and now the cathedral halls are dedicated as Royal enjoy its rich palette of colours in natural surroundings culture, Arab customs and foods all frequented in Chapel, the burial place of the kings’ mausoleum for while you are on the journey to Madrid. -

Teori Arsitektur 03

•Victorian architecture 1837 and 1901 UK •Neolithic architecture 10,000 BC-3000 BC •Jacobethan 1838 •Sumerian architecture 5300 BC-2000 BC •Carpenter Gothic USA and Canada 1840s on •Soft Portuguese style 1940-1955 Portugal & colonies •Ancient Egyptian architecture 3000 BC-373 AD •Queenslander (architecture) 1840s–1960s •Ranch-style 1940s-1970s USA •Classical architecture 600 BC-323 AD Australian architectural styles •New towns 1946-1968 United Kingdom Ancient Greek architecture 776 BC-265 BC •Romanesque Revival architecture 1840–1900 USA •Mid-century modern 1950s California, etc. Roman architecture 753 BC–663 AD •Neo-Manueline 1840s-1910s Portugal & Brazil •Florida Modern 1950s or Tropical Modern •Architecture of Armenia (IVe s - XVIe s) •Neo-Grec 1848 and 1865 •Googie architecture 1950s USA •Merovingian architecture 400s-700s France and Germany •Adirondack Architecture 1850s New York, USA •Brutalist architecture 1950s–1970s •Anglo-Saxon architecture 450s-1066 England and Wales •Bristol Byzantine 1850-1880 •Structuralism 1950s-1970s •Byzantine architecture 527 (Sofia)-1520 •Second Empire 1865 and 1880 •Metabolist Movement 1959 Japan •Islamic Architecture 691-present •Queen Anne Style architecture 1870–1910s England & USA •Arcology 1970s-present •Carolingian architecture 780s-800s France and Germany Stick Style 1879-1905 New England •Repoblación architecture 880s-1000s Spain •Structural Expressionism 1980s-present Eastlake Style 1879-1905 New England •Ottonian architecture 950s-1050s Germany Shingle Style 1879-1905 New England •Postmodern architecture 1980s •Russian architecture 989-1700s •National Park Service Rustic 1872–present USA •Romanesque architecture 1050-1100 •Deconstructivism 1982–present •Chicago school (architecture) 1880s and 1890 USA •Norman architecture 1074-1250 •Memphis Group 1981-1988 •Neo-Byzantine architecture 1882–1920s American •Blobitecture 2003–present •Gothic architecture •Art Nouveau/Jugendstil c. -

Romanesque Architecture and the Scenery

Index 13 Prefaces 31 Abbreviations 33 Chapter I – The Romanesque Architecture and the Scenery 35 Romanesque Architecture 39 The Romanesque in Portugal 45 The Romanesque in the Sousa Valley 53 Dynamics of the Artistic Heritage in the Modern Period 62 Territory and Landscape in the Sousa Valley in the 19th and 20th centuries 69 Chapter II – The Monuments of the Route of the Romanesque of the Sousa Valley 71 Church of Saint Peter of Abragão 73 1. The church in the Middle Ages 77 2. The church in the Modern Period 77 2.1. Architecture and space distribution 79 2.2. Gilding and painting 81 3. Restoration and conservation 83 Chronology Romanesque Architecture 35 Between the late 10th century and the early 11th century, Western Europe accuses a slow renovation accompanied by a remarkable building surge. In this period, the regional differences concerning ar- chitecture are still much accentuated. While the South witnesses the development of the so-called first meridional Romanesque art, in the North of France and in the territory of the Otonian Empire the large wood-covered constructions of Carolingian tradition prevail. However, it is throughout the second half of the 11th century and the early 12th century that a series of political, social, economical and religious transformations will lead to the appearance and expansion of the Romanesque style. A greater political stability is then followed by a slow but significant demographic growth. In the 11th century, progress in the farming techniques will provide better crops and a visible improvement in the population’s eating habits and life conditions. -

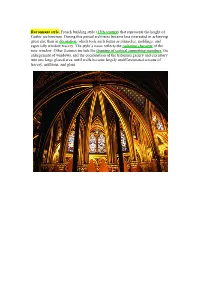

Rayonnant Style, French Building Style (13Th Century) That Represents the Height of Gothic Architecture

Rayonnant style, French building style (13th century) that represents the height of Gothic architecture. During this period architects became less interested in achieving great size than in decoration, which took such forms as pinnacles, moldings, and especially window tracery. The style’s name reflects the radiating character of the rose window. Other features include the thinning of vertical supporting members, the enlargement of windows, and the combination of the triforium gallery and clerestory into one large glazed area, until walls became largely undifferentiated screens of tracery, mullions, and glass. Flamboyant style, phase of late Gothic architecture in 15th-century France and Spain. It evolved out of the Rayonnant style’s increasing emphasis on decoration. Its most conspicuous feature is the dominance in stone window tracery of a flamelike S- shaped curve. Wall surface was reduced to the minimum to allow an almost continuous window expanse. Structural logic was obscured by covering buildings with elaborate tracery. Flamboyant Gothic, which became increasingly ornate, gave way in France to Renaissance forms in the 16th century. Perpendicular style, Phase of late Gothic architecture in England roughly parallel in time to the French Flamboyant style. The style, concerned with creating rich visual effects through decoration, was characterized by a predominance of vertical lines in stone window tracery, enlargement of windows to great proportions, and conversion of the interior stories into a single unified vertical expanse. Fan vaults, springing from slender columns or pendants, became popular. In the 16th century, the grafting of Renaissance elements onto the Perpendicular style resulted in the Tudor style. Manueline, Portuguese Manuelino, particularly rich and lavish style of architectural ornamentation indigenous to Portugal in the early 16th century. -

Mazagan (Morocco) Opened Leading to the Main Street, the Rua Da Carreira, and to the Seagate

fort. During the time of the French Protectorate the ditch was filled in with earth and a new entrance gate was Mazagan (Morocco) opened leading to the main street, the Rua da Carreira, and to the Seagate. Along this street are situated the best No 1058 Rev preserved historic buildings, including the Catholic Church of the Assumption and the cistern. Two Portuguese religious ensembles are still preserved in the citadel. Our Lady of the Assumption is a parish church 1. BASIC DATA built in the 16th century; it has a rectangular plan (44m x 12m), a single nave, a choir, a sacristy, and a square bell State Party: Morocco tower. The second structure is the chapel of St Sebastian Name of property: Portuguese City of Mazagan (El Jadida) sited in the bastion of the same name. Location: Region: Doukkala-Abda, Province El The 19th century Mosque in front of the Church of the Jadida Assumption delimits the urban square, the Praça Terreiro, which opens toward the entrance of the city. The minaret Date received: 31 April 2004 of the mosque is an adaptation of the old Torre de Rebate, Category of property: originally part of the cistern, showing historical continuity. In terms of the categories of cultural property set out in A part of the ensemble in the citadel is the Cistern, the Article 1 of the 1972 World Heritage Convention, this is a design of which is attributed to Joao Castilho. The building group of buildings. consists of a nearly square plan (47m x 56m), with three halls on the north, east, and south sides, and four round Brief description: towers: Torre da Cadea (of the prison) in the west, Torre de Rebate in the north, the Tower of the Storks in the east, The Portuguese fortification of Mazagan, now part of the and the ancient Arab tower of El-Brija in the south. -

The Science of Architecture Representations of Portuguese National Architecture in the 19Th Century World Exhibitions: Archetypes, Models and Images

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UPCommons. Portal del coneixement obert de la UPC Quaderns d’Història de l’Enginyeria volum xiii 2012 THE SCIENCE OF ARCHITECTURE REPRESENTATIONS OF PORTUGUESE NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE IN THE 19TH CENTURY WORLD EXHIBITIONS: ARCHETYPES, MODELS AND IMAGES Paulo Simões Rodrigues [email protected] The influence of positivist philosophy on Portuguese intellectuals became evident from the 1870s. In a very symptomatic way, this influence exerted itself on the dearest values of romantic culture: nationalism. Indeed, it is in texts by authors for whom the positivist doctrine is most discernible that we find nationalist romantic idealism (based on a deitistic or metaphysical transcendence) is progressively replaced by a patriotic spirit rebuilt accord- ing to the parameters of positive science. In other words, it was based on a reading of History that now privileged the impermeable certainty of facts assessed by a methodology taken from natural science. It was believed that on the basis of a positive historiography, nationalism could achieve its main aim since romanticism: the regeneration of the nation – a belief deriving from the primordial objective of the positivist interpretation of social phenomena, the regeneration of societies. Within this context, and as had already been the case with romanticism, art in general and architecture in particular become of fundamental ideological importance as a material, figurative and aesthetic demonstration of the past’s positivist interpretation. It was Hippolyte Taine (1828-1893) who applied the positive scientific method to the arts using Auguste Comte’s theory explaining social phenom- ena as his base. -

The Colonial Architecture of Minas Gerais in Brazil*

THE COLONIAL ARCHITECTURE OF MINAS GERAIS IN BRAZIL* By ROBERT C. SMITH, JR. F ALL the former European colonies in the New World it was Brazil that most faithfully and consistently reflected and preserved the architecture of the mother-country. In Brazil were never felt those strange indigenous influences which in Mexico and Peru produced buildings richer and more complicated in design than the very models of the peninsular Baroque.' Brazil never knew the exi gencies of a new and severe climate necessitating modifications of the old national archi tectural forms, as in the French and English colonies of North America, where also the early mingling of nationalities produced a greater variety of types of construction. And the proof of this lies in the constant imitation in Brazil of the successive styles of architecture in vogue at Lisbon and throughout Portugal during the colonial period.2 From the first establish- ments at Iguarassi3 and Sao Vicente4 down to the last constructions in Minas Gerais, the various buildings of the best preserved colonial sites in Brazil-at Sao Luiz do Maranhao,5 in the old Bahia,6 and the earliest Mineiro7 towns-are completely Portuguese. Whoever would study them must remember the Lusitanian monuments of the period, treating Brazil * The findings here published are the result in part of guesa), circa 1527. researches conducted in Brazil in 1937 under the auspices 2. The Brazilian colonial period extends from the year of the American Council of Learned Societies. of the discovery, 1500, until the establishment of the first i. In Brazil I know of only two religious monuments Brazilian empire in 1822. -

“Mosteiro Dos Jerónimos” Text & Photos by Bruce Hamilton, AIA

“Mosteiro dos Jerónimos” Text & Photos by Bruce Hamilton, AIA Lisbon, Portugal’s capital city, is a ramshackle but charming mix of now and then. Vintage trolleys shiver up and down hills, bird-stained statues mark grand squares, taxis rattle and screech through cobbled lanes while the locals and tourists sip cappuccino in Art Nouveau cafes. It’s a city of faded iron work balconies, multicolored tiles and mosaic sidewalks of bougainvillea and red tile roofs with antique TV antennas. Here at the far western edge of Europe prices are reasonable, the people are warm and the Partial View of Mosteiro dos Jerónimos pace of life slows. The grand Belém District offers a look to Lisbon’s historic architecture and seafaring glory…. from the 16th Century Monastery of Jerónimos to the many museums throughout Lisbon. The Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, also known as the Jerónimos Monastery, is a UNESCO world Heritage site located in Lisbon’s Belém district. Exemplifying Portugal’s Manueline style –a highly ornate style of architecture – the monastery was built during the Age of Discoveries. South Portal The monastery’s south portal is a stunning example of Manueline architecture at its most exuberant. The richly decorated 32-meter door is the visual center of the façade facing the River Tagus. According to our local tour guide, the design was created by master builder, João de Castillio, the author of the “side door” as it became known. Carved like filigree, the ornate stonework is brought to life by an elaborate collection of 40-odd statues set into the pillars that flank the door, figurines that include Henry the Navigator, St Vaulted Ceiling Jerome and Our Lady of the Three Nights.