The Christ-Figure in Popular Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

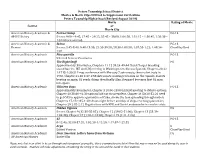

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

Review Essay Faith and Film

RELIGION and the ARTS Religion and the Arts 13 (2009) 595–603 brill.nl/rart Review Essay Faith and Film David McNutt University of Cambridge Austin, Ron. In a New Light: Spirituality and the Media Arts. Grand Rapids MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2007. Pp. x + 95 + illus- trations. $12.00 paper. Humphries-Brooks, Stephenson. Cinematic Savior: Hollywood’s Making of the American Christ. London and Westport CT: Praeger Publishers, 2006. Pp. x + 160. $39.95 cloth. Malone, Peter, ed. Th rough a Catholic Lens: Religious Perspectives of Nine- teen Film Directors From Around the World. Communication, Culture, and Religion Series, eds. Paul J. Soukup, S.J. and Fran Plude. Lanham MD, Boulder CO, New York, and Plymouth, England: Sheed and Ward Books Division of Rowman and Littlefi eld Publishers, 2007. Pp. vi + 272. $25.95 paper. Walsh, Richard. Finding St. Paul in Film. New York and London: T. and T. Clark, 2005. Pp. vi + 218 + illustrations. $29.95 paper. * he dynamic relationship between religious faith and fi lm may be seen Tthrough a number of diff erent lenses. Th is essay will evaluate four examples of the growing number of recent books that address this connec- tion. Th e titles featured here include a volume about Hollywood’s portray- als of Jesus Christ on screen, an interpretation of fi lms in light of the fi gure and theology of Paul, a study of the infl uence of Catholicism upon the © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2009 DOI: 10.1163/107992609X12524941450244 596 D. McNutt / Religion and the Arts 13 (2009) 595–603 work of directors from around the world, and a book investigating the pos- sibility of developing one’s spirituality through fi lmmaking. -

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009 Annotations and citations (Law) -- Arizona. SHEPARD'S ARIZONA CITATIONS : EVERY STATE & FEDERAL CITATION. 5th ed. Colorado Springs, Colo. : LexisNexis, 2008. CORE. LOCATION = LAW CORE. KFA2459 .S53 2008 Online. LOCATION = LAW ONLINE ACCESS. Antitrust law -- European Union countries -- Congresses. EUROPEAN COMPETITION LAW ANNUAL 2007 : A REFORMED APPROACH TO ARTICLE 82 EC / EDITED BY CLAUS-DIETER EHLERMANN AND MEL MARQUIS. Oxford : Hart, 2008. KJE6456 .E88 2007. LOCATION = LAW FOREIGN & INTERNAT. Consolidation and merger of corporations -- Law and legislation -- United States. ACQUISITIONS UNDER THE HART-SCOTT-RODINO ANTITRUST IMPROVEMENTS ACT / STEPHEN M. AXINN ... [ET AL.]. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y. : Law Journal Press, c2008- KF1655 .A74 2008. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Consumer credit -- Law and legislation -- United States -- Popular works. THE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION GUIDE TO CREDIT & BANKRUPTCY. 1st ed. New York : Random House Reference, c2006. KF1524.6 .A46 2006. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Construction industry -- Law and legislation -- Arizona. ARIZONA CONSTRUCTION LAW ANNOTATED : ARIZONA CONSTITUTION, STATUTES, AND REGULATIONS WITH ANNOTATIONS AND COMMENTARY. [Eagan, Minn.] : Thomson/West, c2008- KFA2469 .A75. LOCATION = LAW RESERVE. 1 Court administration -- United States. THE USE OF COURTROOMS IN U.S. DISTRICT COURTS : A REPORT TO THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE ON COURT ADMINISTRATION & CASE MANAGEMENT. Washington, DC : Federal Judicial Center, [2008] JU 13.2:C 83/9. LOCATION = LAW GOV DOCS STACKS. Discrimination in employment -- Law and legislation -- United States. EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION : LAW AND PRACTICE / CHARLES A. SULLIVAN, LAUREN M. WALTER. 4th ed. Austin : Wolters Kluwer Law & Business ; Frederick, MD : Aspen Pub., c2009. KF3464 .S84 2009. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Norman Jewison: Commercial Success, Critical Failure

Norman Jewison: Commercial Success, Critical Failure An Honors Thesi s (1 D c199) by Ant.hnny L. Beeson Thes is Di reel.or Hall SUit.e Univprsit:,,- ('lune i e ,I nd i ana February, 1987 f'>...;pec\.pd dat(~ of graduation: >Ja;.- 19M! Sc '2.0 \! ·1 ' ... 1he.:;i:J L.D .. d\J·f2;'( I ;;';;"1 I QS7 , BJ.f4 Table of Contents In t roduc~ T i. on .. Commen t a 1':'>- on: F. i . ;:-; . r ..... 6 .And Jusr.icp for Ai ] 0 1:2 T h p f 0 \J r f, Lm s j n rom par j s r' n . l ;) Jewison as a riirertor. 1 I Cone 1 us jon .•.• 1 H R i. hI i og raph:v •. I~ Introduction The f ~ I m s () f '\ 0 r man J tCO~'; i son are a stu d :.~ 1 n C Cl n t nl s t s . h 11 i ] e r-tlmost Cill of t.he fi Ims in Ci (1irr>ctin!:!, car'eer hhi('h t)(~gan In 1::lt:i2 hCi n=~ been successful, thpy ha\e alsn bf~en (-h('> c.;llh.)(·et ni neg;-lt \\-P, !'-.()met JOlt'S revIews from film C I' j t. I rs . for I-',pst J) reet.or, In the Heat Flddler' un tl:e h'o(~f, oid not go unsC'athpd. ( Fin I p r, 2 (i ( - 2 () 8 i (,\1 0 cit z, 1 H b - j 9 j ) fn the se(' t -j ons on :.. 0 r m Ci 'I ,J e his () n in the I ~1 i-~; e d i T. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

C.A.S.E. Recommended Adoption Movies

C.A.S.E. Recommended Adoption Movies Movies Appropriate for Children: Movies Appropriate for Adults: Angels in the Outfield Admission Rear Window Anne of Green Gables Antwone Fisher Second Best Annie (both versions) Babbette’s Feast Secrets and Lies Cinderella w/Brandy & Whitney Houston Blossoms in the Dust Singing In The Rain Despicable Me Catfish & Black Bean Soldiers Sauce Despicable Me 2 Children of Paradise St. Vincent Free Willy Cider House Rules Star Wars Trilogy Harry Potter series Cinema Paradiso The 10 Commandments Kung Fu Panda (1 and 2) Citizen Kane/Zelig The Big Wedding Like Mike CoCo—The Story of CoCo The Deep End of the Lilo and Stitch Chanell Ocean Little Secrets Come Back Little Sheba The Joy Luck Club Martian Child Coming Home The Key of the Kingdom Meet the Robinsons First Person Plural The King of Masks Prince of Egypt Flirting with Disaster The Miracle Stuart Little Greystroke The Official Story Stuart Little 2 High Tide The Searchers Superman & Superman (2013) I Am Sam The Spit Fire Grill Tarzan Into the Arms of The Truman Show The Country Bears Strangers The Kid Juno Thief of Bagdad The Lost Medallion King of Hearts To Each His Own The Odd Life of Timothy Green Les Miserables White Oleander The Rescuers Down Under Lovely and Amazing Loggerheads The Jungle Book Miss Saigon Then She Found Me Orphans Immediate Family Philomena www.adoptionsupport.org . -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE in DOMBEY and SON Sarah Flenniken John Carroll University, [email protected]

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Essays Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2017 TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON Sarah Flenniken John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Flenniken, Sarah, "TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON" (2017). Masters Essays. 61. http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays/61 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Essays by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOUCHED BY LOVE: FLORENCE AS CHRIST-FIGURE IN DOMBEY AND SON An Essay Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts & Sciences of John Carroll University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Sarah Flenniken 2017 The essay of Sarah Flenniken is hereby accepted: ______________________________________________ __________________ Advisor- Dr. John McBratney Date I certify that this is the original document ______________________________________________ __________________ Author- Sarah E. Flenniken Date A recent movement in Victorian literary criticism involves a fascination with tactile imagery. Heather Tilley wrote an introduction to an essay collection that purports to “deepen our understanding of the interconnections Victorians made between mind, body, and self, and the ways in which each came into being through tactile modes” (5). According to Tilley, “who touched whom, and how, counted in nineteenth-century society” and literature; in the collection she introduces, “contributors variously consider the ways in which an increasingly delineated touch sense enabled the articulation and differing experience of individual subjectivity” across a wide range of novels and even disciplines (1, 7). -

How to Read Literature Like a Professor

How to Read Literature Like a Professor Author: Thomas C. Foster Adapted by: Miss Barrett Keys to Studying Literature • Read with a pen in hand! • Start looking for these things: Symbols Patterns Intertextuality Devices Allusions Be an Observer: Go all “Sherlock” on it. Notice Things! Ask yourself What does it mean? Why is it there? How does it add to our understanding? Take risks. Guess! Then Guess Again. Make a connection to your life, other texts, and the world. The Basics Setting (Ask: why this setting?) Plot (Consider: foreshadowing, development, turning point, climax, originality) Character (consider types, development, realism) Theme (the most important, ponder the point) Point of View (perspective, does it matter?) Conflict (type, kind {Man vs ____}, introduction, resolution?) Style (ask why it was written this way, is it effective, innovative, imitative?) Now, more things to notice . Context Matters Understand that every book is written against its own social, historical, cultural, and personal background. We don’t have to accept the values of another culture to sympathetically step into the story and recognize universal qualities present there. Now, Where Have I Seen This Before? There is no such thing as a wholly original work of literature. Every new story builds on previous stories. Intertextuality: recognizing the connections between one story and another deepens our appreciation and experience, brings multiple layers of meaning to the text, of which we may not be conscious. Connections might be made