Introduction 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children of the Intervention

CHILDREN OF THE INTERVENTION Aboriginal Children Living in the Northern Territory of Australia A Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child June 2011 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 CHILDREN OF THE INTERVENTION Aboriginal Children Living in the Northern Territory of Australia A Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child Prepared by: Michel e Harris OAM Georgina Gartland June 2011 1 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 2 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5‐6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6‐7 BASIC HEALTH AND WELFARE Overcrowding, Poor Health and Housing 8‐11 Child Nutrition 11‐13 Other Pressures on Family Life 14‐15 SPECIAL PROTECTION MEASURES Affirming Culture 16‐17 EDUCATION, LEISURE AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES Education 18‐20 CONCLUSION 20 Appendices I Statement by Aboriginal Elders of the Northern Territory ‘To The People of Australia’ 21 ii Homeland Learning Centres (HLC) 22‐23 iii Comparison Between Two Schools 24 iv Build A Future For Our Children – Gawa School 25‐27 3 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 4 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 Introduction Aboriginal children living in the prescribed areas of the Northern Territory live under legislation that does not affect Aboriginal children in any other parts of Australia, or any other children who live in Australia whatever their ethnic grouping. It is for this reason that we are providing a complementary report to the Australian NGO Report Listen to Children in order to draw specific attention to the situation of children living in the Northern Territory. This legislation, known as Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment (Welfare Reform and Reinstatement of the Racial Discrimination Act) 2009, with small changes, has dominated the lives of all Northern Territory Aboriginal people since 21 June 2007. -

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

Annual Report 2010–2011 © Northern Territory Government 2011

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING Annual Report 2010–2011 © Northern Territory Government 2011 Northern Territory Department of Education and Training GPO Box 4821 Darwin NT 0801 www.det.nt.gov.au Published by the Department of Education and Training Reproduction of this work in whole or in part for educational purposes within an educational institution and on condition that it is not offered for sale is permitted by the Northern Territory Department of Education and Training. ISSN 1448-0174 Design by Sprout Creative ii DET ANNUAL REPORT 2010–11 DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING Office of the Chief Executive Level 14, Mitchell Centre 55–59 Mitchell Street, Darwin Postal address GPO Box 4821 DARWIN NT 0801 Tel (08) 899 95857 Fax (08) 899 93537 [email protected] The Hon Chris Burns MLA Minister for Education and Training Parliament House DARWIN NT 0800 Dear Minister RE: Department of Education and Training 2010–11 Annual Report I am pleased to present this report on the Northern Territory Department of Education and Training’s activities from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2011 in line with section 28 of the Public Sector Employment and Management Act and section 10 of the Education Act. To the best of my knowledge and belief as Accountable Officer, pursuant to section 13 of the Financial Management Act, the system of internal control and audit provides reasonable assurance that: proper records of all transactions affecting the agency are kept and that the department’s employees observe the provisions of the Financial Management Act, -

Children of the Intervention

CHILDREN OF THE INTERVENTION Aboriginal Children Living in the Northern Territory of Australia A Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child June 2011 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 CHILDREN OF THE INTERVENTION Aboriginal Children Living in the Northern Territory of Australia A Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child Prepared by: Michel e Harris OAM Georgina Gartland June 2011 1 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 2 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5‐6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6‐7 BASIC HEALTH AND WELFARE Overcrowding, Poor Health and Housing 8‐11 Child Nutrition 11‐13 Other Pressures on Family Life 14‐15 SPECIAL PROTECTION MEASURES Affirming Culture 16‐17 EDUCATION, LEISURE AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES Education 18‐20 CONCLUSION 20 Appendices I Statement by Aboriginal Elders of the Northern Territory ‘To The People of Australia’ 21 ii Homeland Learning Centres (HLC) 22‐23 iii Comparison Between Two Schools 24 iv Build A Future For Our Children – Gawa School 25‐27 3 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 4 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 Introduction Aboriginal children living in the prescribed areas of the Northern Territory live under legislation that does not affect Aboriginal children in any other parts of Australia, or any other children who live in Australia whatever their ethnic grouping. It is for this reason that we are providing a complementary report to the Australian NGO Report Listen to Children in order to draw specific attention to the situation of children living in the Northern Territory. This legislation, known as Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment (Welfare Reform and Reinstatement of the Racial Discrimination Act) 2009, with small changes, has dominated the lives of all Northern Territory Aboriginal people since 21 June 2007. -

The Effect of Quarantining Welfare on School Attendance in Indigenous

The Effect of Quarantining Welfare on School Attendance in Indigenous Communities∗ Deborah Cobb-Clark University of Sydney Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) ARC Centre of Excellence for Children and Families Over the Life Course Nathan Kettlewelly Stefanie Schurer University of Sydney University of Sydney Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) Sven Silburn Menzies School of Health Research August 2017 ∗Acknowledgements here: We acknowledge (so far) valuable feedback from Heather d'Antoine, Matthew Gray, Nicholas Biddle, Jim Smith, Liz Moore, Wes Miller and David Cooper (AMSANT, initiated), Sharon Stone, Julie Brimblecombe, Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews, and Maggie Walters. This study used data from the Northern Territory (NT) Early Childhood Data Linkage Project, \Improving the developmental outcomes of NT Children: A data linkage study to inform policy and practice across the health, education and family services sectors", which is funded through a Partnership Project between the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the NT Government. This study uses administrative data obtained from the NT Department of Education through this NHMRC Partnership Project. The analysis conducted in this project will follow the NHMRC Values and Ethics: Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research (2003) and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) Guidelines for Ethical Research in Australian Indigenous Studies (2012) (Reciprocity, Respect, Equality, Responsibility, Survival and Protection, Spirit and Integrity). The researchers are bound by, and the research analysis will comply with, all ethical standards outlined in the ethics agreement HREC Reference Number: 2016-2611 Project Title: Improving the developmental outcomes of Northern Territory children: A data linkage study to inform policy and practice in health, family services and education (Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research). -

EXPERIMENTS in SELF-DETERMINATION Histories of the Outstation Movement in Australia

EXPERIMENTS IN SELF-DETERMINATION Histories of the outstation movement in Australia EXPERIMENTS IN SELF-DETERMINATION Histories of the outstation movement in Australia Edited by Nicolas Peterson and Fred Myers MONOGRAPHS IN ANTHROPOLOGY SERIES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Experiments in self-determination : histories of the outstation movement in Australia / editors: Nicolas Peterson, Fred Myers. ISBN: 9781925022896 (paperback) 9781925022902 (ebook) Subjects: Community life. Community organization. Aboriginal Australians--Social conditions--20th century. Aboriginal Australians--Social life and customs--20th century. Other Creators/Contributors: Peterson, Nicolas, 1941- editor. Myers, Fred R., 1948- editor. Dewey Number: 305.89915 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents List of maps . vii List of figures . ix List of tables . xi Preface and acknowledgements . xiii 1 . The origins and history of outstations as Aboriginal life projects . 1 Fred Myers and Nicolas Peterson History and memory 2 . From Coombes to Coombs: Reflections on the Pitjantjatjara outstation movement . 25 Bill Edwards 3 . Returning to country: The Docker River project . 47 Jeremy Long 4 . ‘Shifting’: The Western Arrernte’s outstation movement . 61 Diane Austin-Broos Western Desert complexities 5 . History, memory and the politics of self-determination at an early outstation . -

News from Mäpuru

News from the Whittaker family Hi. Greetings from Mäpuru! I received an email from a Uniting Church minister colleague the other day saying “Hi I haven‟t heard much from you lately how are things going?”. So I thought it might be good to update our friends and colleagues about what is happening with the Whittakers. Just to recap. In July Penny, Dean, Amber and Hannah left SA and moved to Arnhem Land because Penny had been invited to teach in a new Christian School at Mäpuru which was commencing that month. The school had previously been a Homeland Learning Centre associated with Shepherdson College on Elcho Island, which meant teachers came out for a few days each week. The Mäpuru community had been asking the Government and Education Department for many years to let them become a proper school of their own and this had not happened. So after being knocked back once too often they took matters into their own hands and decided to become an independent school under the auspices of the Northern Territory Christian Schools Association (NTCSA). Meanwhile, back with the Whittakers…..Dean took six months leave from his ministry role with Congress in SA, Amber deferred her social work studies with Uni SA and came with us offering to help Penny in the classroom situation while continuing her Uni studies with one distance education topic offered by Charles Darwin Uni (CDU) called “Yolngu Studies”. Hannah enrolled in the Katherine School of the Air studying at year 8 level with Dad as a tutor. Mäpuru had previously had no balanda (non-Aboriginal) residents. -

Senate Select Committee on Regional and Remote Indigenous Communities

won't be able to visit Darwin anymore because I know those white people will look at me and see me as a child abuser." Not long after the NTER was announced a Yolngu man living at Galwin'ku, Elcho Island rang, he was distraught. So many of his younger extended family members were attempting suicide. He said, "I don't know what to do, all we hear government people and TV reporters speak about, everything we read in newspapers tells lies about us, the news say all Yolngu people are substance abusers and child abusers, we are not. These stories are having a bad affect, these stories make us feel bad, they stories are increasing the level of substance abuse, and these things have made a big increase in attempted suicides." A respected matriarch and grandmother whose family lived on Elcho Island, and who had lived and worked in Darwin for many years, "me and my families can no longer do our shopping during the day. (White) people look at us as if we are child abusers, we are not we are honest good people." She felt that after the "Intervention" she and all the women she knew were identified as a child molester by white Australians. She blames the government and the media for the way they portrayed all black Northern Territorians. Not long after the introduction of the NTER she left her work and Darwin, she returned to her family. This was the only way for her to maintain a positive sense of self. The immediate, and continuing impact of the NTER has been to belittle and marginalise the NT's First Nation peoples from the wider predominately white society. -

Indigenous Women Leaders in Yolngu, Australia-Wide and International Contexts

2. Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts Gwenda Baker,1 Joanne Garŋgulkpuy2 and Kathy Guthadjaka3 This chapter explores the extraordinary growth in political leadership over the past 30 years among Indigenous women from a remote community. It is representative of a wider Australian phenomenon: the intense participation in democratic affairs by Indigenous women. These are two women from among many more: there are others who are participating at a similar level in this and other communities in the Northern Territory and elsewhere within Australia. Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy are two Yolngu women leaders from Elcho Island in the Northern Territory, a small island 500 km north-east of Darwin. Geographically isolated, they occupy a difficult space in leadership and democratic action due to their position between two worlds: the Yolngu world and the mainstream Australian world. They have to remain true to their connections to clan and country while working with the wider political and intellectual worlds within Australia and overseas. Jackie Huggins explains that for an Indigenous leader, ‘[l]eadership means that you need to respect differences of views and start from where people are at— not where you would want them to be. The trick is to listen, listen, listen, and then act.’4 Both Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy refer frequently with their elders, raising each individual issue before a consensus is reached. They speak for the community, not themselves. Their leadership is different in the ways that Amanda Sinclair identifies as less ego-driven, more spiritual, with different sources of power and responsibility.5 Ego is often set aside to respect others and their relationships. -

Indigenous Education in the Northern Territory

Policy Monographs Indigenous Education in the Northern Territory Helen Hughes www.cis.org.au Indigenous Education in the Northern Territory Helen Hughes CIS Policy Monograph 83 2008 CIS publications on Indigenous affairs Book Helen Hughes, Lands of Shame: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ‘Homelands’ in Transition (Sydney: CIS, 2007). Issue Analysis No. 88 Kava and after in the Nhulunbuy (Gulf of Carpenteria) Hinterland Helen Hughes No. 86 What is Working in Good Schools in Remote Indigenous Communities? Kirsten Storry No. 78 Indigenous Governance at the Crossroads: The Way Forward John Cleary No. 73 Tackling Literacy in Remote Aboriginal Communities Kirsten Storry No. 72 School Autonomy: A Key Reform for Improving Indigenous Education Julie Novak No. 65 Education and Learning in an Aboriginal Community Veronica Cleary No. 63 The Economics of Indigenous Deprivation and Proposals for Reform Helen Hughes No. 55 Lessons from the Tiwi Islands John Cleary No. 54 A New Deal for Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in Remote Communities Helen Hughes and Jenness Warin Also by Helen Hughes Helen Hughes, “Strangers in Their Own Country: A Diary of Hope,” Quadrant 52:3 (March 2008). Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................. vii An agenda for action ................................................................................. vii History .................................................................................................................. 1 Northern -

A History of Donydji Outstation, North-East Arnhem Land Neville White

16 A history of Donydji outstation, north-east Arnhem Land Neville White The first official exploration of Yolngu country was by David Lindsay, who, in 1883, travelled the western edge of Wagilak land, following the Goyder River into the Arafura Swamp, where he first encountered Yolngu people and in large numbers. Soon after, in 1885, the Florida cattle station was established when a herd of cattle driven from Queensland arrived (Berndt and Berndt 1954). This was a short-lived but violent frontier, with memories of conflict and atrocities persisting today. Soon after the closure of Florida, a Methodist Overseas Mission was founded, in 1923, on Milingimbi Island, off the north-western coast of north-east Arnhem Land (Berndt and Berndt 1954). This mission settlement attracted Yolngu people from a wide area, many of whom settled on the mission. Others, like the families who set up the Donydji outstation, visited periodically for supplies such as tobacco and sugar—commodities that were also occasionally obtained from the Mainoru cattle station and Roper River Mission Station to the south. These journeys often took many months. During World War II, Milingimbi came under air attack by the Japanese, and the Reverend Harold Shepherdson moved to a new Methodist mission site on Elcho Island, a little to the east. Shepherdson later transported, in his own single-engine plane, some food supplies and clothes to the newly created Mirrngadja outstation, using an airstrip he had helped construct in 1959 (Shepherdson 1981). In 1969, the Reverend started Lake Evella (now known as Gapuwiyak) as an outpost of the Elcho Island Mission, so as to engage with 323 ExPERIMENTS IN SELF-Determination Yolngu people further inland and to mill native cypress pine growing in the vicinity (Shepherdson 1981). -

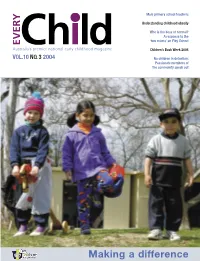

Making a Difference

Male primary school teachers Understanding childhood obesity Who is the boss of normal? A response to the ‘two mums’ on Play School Australia’s premier national early childhood magazine Children’s Book Week 2004 VOL.10 NO. 3 2004 No children in detention: Passionate members of the community speak out Making a difference Feeling out of the loop? Stay informed … SUBSCRIBE NOW! Published nationally each week PUBLISHED NATIONALLY EACH WEEK Everyday Learning Series Subscribe to CSNews This new series focuses attention on the everyday ways in which children can be supported in their growth and A free, weekly, comprehensive, national email development. It is for all those involved in children’s development and newspaper for all children’s services learning, including early childhood professionals in all children’s services, parents, grandparents and others with CSNews will: an ongoing responsibility for young children. • Contain all the current news and information about children’s services $40.00 for one year’s subscription (4 issues) incl. p&h • Create a national network of children’s services centred on news and information. Research in Practice Series Early Childhood Australia supports, endorses and will collaborate with Don’t miss out on this highly popular series. the production of CSNews. We have agreed editorial guidelines with The topics are different each edition, and recent titles have CSNews and have taken specifi c steps to protect your email address been re-printed due to popular demand! Past issues have from unauthorised usage. focused on behaviour, autism, boys and planning. $42.40 for one year’s subscription (4 issues) incl.