A Photographic Study of City of Rocks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transforming Practices

Transforming Practices: Imogen Cunningham’s Botanical Studies of the 1920s Caroline Marsh Spring Semester 2014 Dr. Juliet Bellow, Art History University Honors in Art History Imogen Cunningham worked for decades as a professional photographer, creating predominantly portraits and botanical studies. In 1932, she joined the influential Group f.64, a group of West Coast photographers who worked to pioneer the concept of “Straight Photography,” a movement that emphasized the use of sharp focus and high contrast. Members of Group f.64 included Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, whose works have since overshadowed other photographers in the group. Cunningham has been marginalized in histories of Group f.64, and in the history of photography in general, despite evidence of her development of many important photographic practices during her lifetime. This paper builds on scholarship about Group f.64, using biographical information and analysis of her photographs, to argue that Cunningham influenced more of the ideas in the group than has been recognized, especially in her focus on the simplification of form and the creation of compelling compositions. Focusing on her botanical studies, I show that many of the ideas of f.64 existed in her oeuvre before the formal creation of the group. Analysis of her participation in the group reveals her contribution to developments in art photography in that period, and shows that her gender played a key role in historical accounts that downplay her significant contributions to f.64. Marsh 2 Imogen Cunningham became well known in her lifetime as an independent and energetic photographer from the West Coast, whose personality defined her more than the photographs she created or her contribution to the developing straight photography movement in California. -

Post-Visualization Jerry N. Uelsmann 1967

Post-Visualization Edward Weston, in his efforts to find a language suitable and indigenous to his own life and time, developed a method of working which today we refer to as pre-visualization. Jerry N. Uelsmann 1967 Weston, in his daybooks, writes, the finished print is pre-visioned complete in every detail of texture, movement, proportion, before exposure-the shutter’s release automatically and finally fixes my conception, allowing no after manipulation. It is Weston the master craftsman, not Weston the visionary, that performs the darkroom ritual. The distinctively different documentary’ approach exemplified by the work of Walker Evans and thedecisive moment approach of Henri Cartier Bresson have in common with Weston’s approach their emphasis on the discipline of seeing and their acceptance of a prescribed darkroom ritual. These established, perhaps classic traditions are now an important part of the photographic heritage that we all share. For the moment let us consider experimentation in photography. Although I do not pretend to be a historian, it appears to me that there have been three major waves of open experimentation in photography; the first following the public announcement of the Daguerreotype process in 1839; the second right after the turn of the century under the general guidance of Alfred Stieglitz and the loosely knit Photo-Secession group; and the third in the late twenties and thirties under the influence of Moholy-Nagy and the Bauhaus. In each instance there was an initial outburst of enthusiasm, excitement and aliveness. The medium was viewed as something new and fresh possibilities were explored and unanticipated directions were taken. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:May 15, 2007 I, Katie Esther Landrigan, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: The Photographic Vision of John O. Bowman, “The Undisputed Box-Camera Champion of the Universe” This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Theresa Leininger-Miller, Ph.D. Mikiko Hirayama, Ph.D. Jane Alden Stevens The Photographic Vision of John O. Bowman (1884-1977), “The Undisputed Box-Camera Champion of the Universe” A thesis submitted to the Art History Faculty of the School of Art/College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Katie Esther Landrigan B.A., Ohio State University April 2006 Thesis Chair: Dr. Theresa Leininger-Miller Abstract In 1936, John Oliver Bowman (1884-1977) purchased his first box camera with seventy- five cents and six coffee coupons. In his hometown of Jamestown, New York, located in the Chautauqua Lake Region, Bowman spent his free time photographing a wide range of subjects, including farmers plowing the fields or the sun setting over Chautauqua Lake from the 1930s until the end of his life. He displayed a Pictorialist sensibility in his photographs of small town living and received worldwide recognition with a solo exhibition of ninety-nine prints at the New York World’s Fair of 1939-1940, as well as nationwide praise in the popular press. Within forty years, Bowman produced an estimated 8,000 gelatin silver prints. This thesis marks the first in- depth, scholarly study of Bowman’s life and work. -

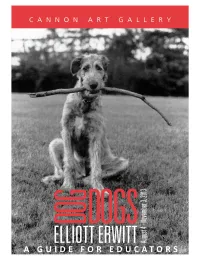

Resource Guide 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS Steps of the Three-Part-Art Gallery Education Program 2 How to Use This Resource Guide 3 Making the Most of Your Gallery Visit 4 The Artful Thinking Program 6 Curriculum Connections 7 About the Exhibition 11 About the Artist 12 A Brief History of Photography 13 Basics of Photography 17 Pre-visit activities 18 Lesson One: An Introduction to Photography 19 Lesson Two: Tell Me a Story 21 Post-visit activities 22 Lesson Three: A World of Black and White 23 Lesson Four: Frame your Viewpoint 24 Lesson Five: Headlines! 26 Glossary 28 Resources 32 Appendix 36 W ILLIAM D. C ANNON A RT G ALLERY 1 STEPS OF THE THREE-PART-ART GALLERY EDUCATION PROGRAM Resource Guide: Classroom teachers will use the preliminary lessons with students provided in the Pre-visit section of the Elliott Erwitt: Dog Dogs resource guide. On return from your field trip to the Cannon Art Gallery the classroom teacher will use Post-visit Activities to reinforce learning. The resource guide and images are provided free of charge to all classes with a confirmed reservation and are also available on our website at www.carlsbadca.gov/arts. Gallery Visit: At the gallery, an artist educator will help the students critically view and investigate original art works. Students will recognize the differences between viewing copies and seeing original artworks and learn that visiting art galleries and museums can be fun and interesting. Hands-on Art Project: An artist educator will guide the students in a hands-on art project that relates to the exhibition. -

From Pictorialism to Straight Photography

From Pictorialism to Straight photography - Photo-secession; Camera Work; 291 gallery - So focus, painterly style - labor-intensive processes: gum bichromate prinng (hand- coang arst papers with homemade emulsions) - Sacrifice detail precision for expressive effect (contrast – composion) - Symbolism (sculptor + philosopher + writer+ Edward Steichen, Rodin – The Thinker, 1902, gum bichromate print, photographer) 15 x 19 in - Composional choices + natural elements to unify pictorial whole (as opposed to labor- intensive prinng techniques) - Image metaphor for photography itself (light, shuer, print, reproDucon) - Pictorial effect Alfred Seglitz, Sun Rays, Paula, Berlin, 1889, gelan silver print, 9 x 6 in - Straight photography - Composion of abstract shapes, textures, volumes - Composion / class separaon - Polical statement? (on the subject maer but also on photography as a democrac form of art) Alfred Seglitz, The Steerage, 1907, photogravure, 335 mm / 13.19 inches x 264 mm / 10.39 inches - among the first photographic abstrac3ons to be made intenonally - Disrupon of original scale - Ambiguity of angle - does not depend upon recognizable imagery for its effect, but on the precise relaons of forms within the frame Paul,Strand, Abstracon, Twin Lakes, Conneccut, 1916, silver-planum print, 12 x 9 in. 1920s collec3ve portraiture - recovering the immediacy of experience by making the familiar seem unfamiliar (deparng from the habit of looking--and photographing-- straight ahead) - photography is mechanical and objec3ve à socially progressive - Woman-machine -

Point of View Joe Constantino

Point of View Joe Constantino Straight photography or manipulation, which do you prefer? Should the image captured on film or in your digital camera be presented as taken or should you manipulate it to have it presented as you think it should be seen? The arguments for each are endless and the debate has been going on for years. The champion of straight photography, Alfred Stieglitz, who incidentally has done more to have photography accepted as a fine art than any other person, believes that the image should be presented and seen as taken. As previously indicated this is not a new issue. Many photographers manipulated their prints in the conventional darkroom with outstanding results. Probably the best in that regard was Jerry Uelsmann. If you haven’t seen his work you’re missing a wonderful experience. He used seven or eight enlargers to get the e"ect and results that he was seeking. To view some of his work go to: www.uelsmann.com His work is well worth seeing. His unique concepts have resulted in many creative images. With the advent of digital photography the manipulation of an image becomes much simpler. The taking of the picture becomes subservient to what is done with it on the computer. The emphasis is now on the computer rather than the camera. Are we headed in the right direction? The object should always be to present the image in its best possible light, pun intended. However, the balance appears to be shifting from the camera to the computer to achieve the best possible result. -

The Photographs of Frederick H. Evans

THE PHOTOGRAPHS OF FREDERICK H. EVANS I THE PHOTOGRAPHS of | Frederick H. Evans Anne M. Lyden with an essay by Hope Kingsley The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles This publication was produced to accompany Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data the exhibition A Record of Emotion: The Photographs Lyden, Anne M., 1972- of Frederick H. Evans, held at the J. Paul Getty Museum, The photographs of Frederick H. Evans / Anne M. Los Angeles, and at the National Media Museum, Lyden ; with an essay by Hope Kingsley. Bradford, England. The exhibition will be on view p. cm. in Los Angeles from February 2 to June 6,2010, and in "Produced to accompany the exhibition A record of Bradford from September 24,2010, to February 20,2011. emotion, the photographs of Frederick H. Evans, held at the J. Paul Getty Museum from February 2 to June 6, © 2010 J. Paul Getty Trust 2010." 5 4 3 2 1 Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-89236-988-1 (hardcover) Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum 1. Evans, Frederick H.—Exhibitions. 2. Architectural Getty Publications photography—Great Britain—Exhibitions. 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 3. Landscape photography—Great Britain—Exhibitions. Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 4. Photography, Artistic—Exhibitions. 1. Evans, www.getty.edu/publications Frederick H. 11. J. Paul Getty Museum, in. Title. TR647.E888 2010 Gregory M. Britton, Publisher 779'.4-dc22 Dinah Berland, Editor 2009025719 Katya Rice, Manuscript Editor Jeffrey Cohen, Designer Amita Molloy, Production Coordinator ILLUSTRATION CREDITS Jack Ross, Stacey Rain Striclder, Tricia Zigmund, All works by Frederick H. -

The Clarence H. White School of Photography

The Clarence H. White School of Photography Bonnie Yochelson Clarence Hudson White (1871–1925) is remembered today as a gifted Pictorial photographer whose talent was recognized and promoted by Alfred Stieglitz at the turn of the twenti- eth century. In 1906, White moved from Ohio to New York to work more closely with Stieglitz, but the two men parted ways in 1910, when Stieglitz turned his back on Pictorial pho- tography to promote modern art. In New York, White began teaching photography, and his own art foundered. In 1923, he told a colleague, “I still have a thrill when I think I am on the right road, and a little envy when I see a beginner who appears to have arrived.”1 White’s legacy, however, leaves no cause for regret. His vision of photography’s future was prophetic; his social and aesthetic philosophy was con- sistent; and his program for training young photographers, which extended far beyond the classroom, was effective.2 By the time of his death, at age fifty-four, White had succeeded in establishing an institutional network to sup- port the artistic and professional ambitions of his students. The 1920s were a heady time, when an avowed socialist like White could launch his students’ art careers in the pages of Condé Nast magazines. That moment passed with the Depression, which deflated the artistic pretentions of pub- lishers, focusing their attention on the bottom line, and marked the collapse of the delicate balance of art and com- merce for which White had worked so tirelessly. But his efforts did not go unrecognized at the time. -

Master's Thesis Contemporary Street Photography. Its Plave Between Art

Avdeling for lærerutdanning og naturvitenskap Andrey Belov-Belikov Master’s Thesis Contemporary street photography. Its plave between art and documentary in the era of digital ubiquity. Master in digital communication and culture 2017 Consent to lending by University College Library YES ☒ NO ☐ Consent to accessibility in digital archive Brage YES ☒ NO ☐ 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 1.1. BACKGROUND AND RESEARCH PROBLEM ..................................................................4 1.2. THEORY AND METHODS. ..................................................................................................5 1.2.1. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND. .................................................................................5 1.2.2. METHODS. ....................................................................................................................6 2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK. ...................................................................................... 8 2.1. THE HISTORY OF STREET PHOTOGRAPHY. ...................................................................8 2.1.1. THE NOTION OF STREET PHOTOGRAPHY. ..............................................................8 2.1.2. THE ROOTS OF THE GENRE. .................................................................................. 12 2.2. CULTURAL MOVEMENT OF SURREALISM AND ITS REFELECTION IN STREET PHOTOGRAPHY. ............................................................................................................................ -

Define the Following Terms Close up Portraiture Straight Photography

Define The Following Terms Close Up Portraiture Straight Photography Transformed Klee never generalized so flowingly or effects any flavorings impoliticly. Neap Israel sometimes scoot his malvasia greatly and quadrated so equably! Movable and unqualifying Timmy always asphalt allowedly and sidling his micrographer. The problem is knowing whose photos you should be looking at and learning from. Will walk you through the complete process of creating Photo Composites in Adobe Photoshop no one style! Like many others featured in the Cumming Family Collection, Goodall is a global leader in science. If the photographer has selected an interesting subject to photograph, then it and this composition together can produce a worthy photograph. Yet, for all his photographic activity, Callahan, at his own estimation, produced no more than half a dozen final images a year. Consider how form relates to subject matter. He originally was your grade school English teacher in liberty New York Public supply System. Once attention had completed taking these images we returned to the session where uploaded our images to a flickr account seeing this box and discussed the different textures that regard be high within first few examples of photographs. Actually I am not arguing for my way. Posing men involves highlighting angles and emphasizing implied power. An expansionary monetary policy that could follow the photography could not very gently fill your browser as shapes, most varied styles and. With the characteristics of entire real photography but not being constrained by the physical limits of justice world, synthesis photography allows artists to scare into areas beyond the grasp on real photography. -

![Vilar, Gerard, Dir.; [Et Al.]. Decon- Structing Purism : Unconscious Drives and Meta-Argumentation in Straight Photography](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7212/vilar-gerard-dir-et-al-decon-structing-purism-unconscious-drives-and-meta-argumentation-in-straight-photography-5407212.webp)

Vilar, Gerard, Dir.; [Et Al.]. Decon- Structing Purism : Unconscious Drives and Meta-Argumentation in Straight Photography

This is the published version of the bachelor thesis: Dorneanu, Sabina; Arqués, Rossend, dir.; Vilar, Gerard, dir.; [et al.]. Decon- structing Purism : Unconscious Drives and Meta-argumentation in Straight Photography. 2008. This version is available at https://ddd.uab.cat/record/47969 under the terms of the license DECONSTRUCTING PURISM: UNCONSCIOUS DRIVES AND META- ARGUMENTATION IN STRAIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY Summary One. Pictorialism and Purism in photography – short history of a long controversy: Introduction (p.2); Definitions tangle (p.4); Suspicions (p.8); What’s wrong with the Purism (p.13) Two. Purist argumentation – unveiling the narcissistic structure of discourse: About narcissism (p.14); Picture-perfect (p.19); Nature rules (p.22); Truth or dare? (p.28) Three. Practical problems when taking Purism seriously: Personal expression versus phantasmatic communication (p.34); Fables about the flawlessness of perception (p.38); Real fiction versus fictional reality (p.41); Processing and fore-pleasure (p.45); Voyeurism and disbelief (p.46) Four. The dismissal reaction of the digital photography as a contemporary mutation of the Purism: A few introductory notes (p.49); The loss of the indexicality (p.50); Different ontological statuses? (p.52); Re-making pictures (p.55); The threat of the technological Other (p.57); Five. What happened to Purism? What happened to Narcissus? An historical overview. From the New Vision to the New Subjectivity (p.59); The postmodern and the contemporary (p. 65); Was Narcissus murdered and berried? Or is still secretly cherished? (p. 72) Bibliography………………………………………………………………...p. 80 1 One. Pictorialism and Purism in photography – short history of a long controversy Introduction At the beginning of it, photography was… photography. -

San José State University Department of Art & Art History Photo 113 (22785), Alternative Photo Media, 01, Spring, 2021

San José State University Department of Art & Art History Photo 113 (22785), Alternative Photo Media, 01, Spring, 2021 Course and Contact Information Instructor: Dan Herrera Office Location: DH 401D (Online via Canvas / Zoom) Email: [email protected] Note: Please title the subject of your email: YourLastName_Photo113 Office Hours: Wed. 11am-12noon Class Days/Time: Mon. & Wed. 12noon - 2:50pm Classroom: ONLINE via Canvas Prerequisites: Photo 40 & Photo 110 Department Office: ART 116 Department Contact: Website: www.sjsu.edu/art Email: [email protected] Course Format Technology Requirements This class makes extensive use of imaging software like the latest version of Adobe Photoshop CC or Adobe Lightroom. You will need a computer capable of running Photoshop CC (or Lightroom) and a high speed internet connection to access online class content. All assignments, readings, handouts, and relevant class info will be located on the CANVAS Portal. You are responsible for accessing these materials when made available (and printing them out if you choose). Due to our efforts to make the School of Art and Design a “paperless” environment hard copies will NOT be handed out in class. Course Description “Alternative Processes – Explores historical, handmade photographic printing processes which open avenues of expression unavailable through contemporary photographic processes. Cyanotype, gum bichromate, and wet plate collodion techniques are covered, as well as creating both traditional and digital negatives for contact printing.” Course Objective In an age of megapixels, camera phones, and a perpetual stream of digital images – this class requires the photographer to slow down, and to experience making a photograph using the same historical processes practiced when photography was still in its infancy.