Photography Goes Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transforming Practices

Transforming Practices: Imogen Cunningham’s Botanical Studies of the 1920s Caroline Marsh Spring Semester 2014 Dr. Juliet Bellow, Art History University Honors in Art History Imogen Cunningham worked for decades as a professional photographer, creating predominantly portraits and botanical studies. In 1932, she joined the influential Group f.64, a group of West Coast photographers who worked to pioneer the concept of “Straight Photography,” a movement that emphasized the use of sharp focus and high contrast. Members of Group f.64 included Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, whose works have since overshadowed other photographers in the group. Cunningham has been marginalized in histories of Group f.64, and in the history of photography in general, despite evidence of her development of many important photographic practices during her lifetime. This paper builds on scholarship about Group f.64, using biographical information and analysis of her photographs, to argue that Cunningham influenced more of the ideas in the group than has been recognized, especially in her focus on the simplification of form and the creation of compelling compositions. Focusing on her botanical studies, I show that many of the ideas of f.64 existed in her oeuvre before the formal creation of the group. Analysis of her participation in the group reveals her contribution to developments in art photography in that period, and shows that her gender played a key role in historical accounts that downplay her significant contributions to f.64. Marsh 2 Imogen Cunningham became well known in her lifetime as an independent and energetic photographer from the West Coast, whose personality defined her more than the photographs she created or her contribution to the developing straight photography movement in California. -

Post-Visualization Jerry N. Uelsmann 1967

Post-Visualization Edward Weston, in his efforts to find a language suitable and indigenous to his own life and time, developed a method of working which today we refer to as pre-visualization. Jerry N. Uelsmann 1967 Weston, in his daybooks, writes, the finished print is pre-visioned complete in every detail of texture, movement, proportion, before exposure-the shutter’s release automatically and finally fixes my conception, allowing no after manipulation. It is Weston the master craftsman, not Weston the visionary, that performs the darkroom ritual. The distinctively different documentary’ approach exemplified by the work of Walker Evans and thedecisive moment approach of Henri Cartier Bresson have in common with Weston’s approach their emphasis on the discipline of seeing and their acceptance of a prescribed darkroom ritual. These established, perhaps classic traditions are now an important part of the photographic heritage that we all share. For the moment let us consider experimentation in photography. Although I do not pretend to be a historian, it appears to me that there have been three major waves of open experimentation in photography; the first following the public announcement of the Daguerreotype process in 1839; the second right after the turn of the century under the general guidance of Alfred Stieglitz and the loosely knit Photo-Secession group; and the third in the late twenties and thirties under the influence of Moholy-Nagy and the Bauhaus. In each instance there was an initial outburst of enthusiasm, excitement and aliveness. The medium was viewed as something new and fresh possibilities were explored and unanticipated directions were taken. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:May 15, 2007 I, Katie Esther Landrigan, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: The Photographic Vision of John O. Bowman, “The Undisputed Box-Camera Champion of the Universe” This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Theresa Leininger-Miller, Ph.D. Mikiko Hirayama, Ph.D. Jane Alden Stevens The Photographic Vision of John O. Bowman (1884-1977), “The Undisputed Box-Camera Champion of the Universe” A thesis submitted to the Art History Faculty of the School of Art/College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Katie Esther Landrigan B.A., Ohio State University April 2006 Thesis Chair: Dr. Theresa Leininger-Miller Abstract In 1936, John Oliver Bowman (1884-1977) purchased his first box camera with seventy- five cents and six coffee coupons. In his hometown of Jamestown, New York, located in the Chautauqua Lake Region, Bowman spent his free time photographing a wide range of subjects, including farmers plowing the fields or the sun setting over Chautauqua Lake from the 1930s until the end of his life. He displayed a Pictorialist sensibility in his photographs of small town living and received worldwide recognition with a solo exhibition of ninety-nine prints at the New York World’s Fair of 1939-1940, as well as nationwide praise in the popular press. Within forty years, Bowman produced an estimated 8,000 gelatin silver prints. This thesis marks the first in- depth, scholarly study of Bowman’s life and work. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

The Radical Camera, New York's Photo League, 1936-1951

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 2 | 2011 Sport et société / Animals and the American Imagination The Radical Camera, New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 Jewish Museum, New York (November 4-March 25, 2012). Commissaire : Mason Klein Marie Cordié Lévy Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/5609 ISSN : 1765-2766 Éditeur AFEA Référence électronique Marie Cordié Lévy, « The Radical Camera, New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 », Transatlantica [En ligne], 2 | 2011, mis en ligne le 14 mai 2012, consulté le 19 avril 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/5609 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 19 avril 2019. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. The Radical Camera, New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 1 The Radical Camera, New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 Jewish Museum, New York (November 4-March 25, 2012). Commissaire : Mason Klein Marie Cordié Lévy 1 En ce printemps 2012 New York apparaît plus que jamais comme le lieu vivant de la photographie. En témoignent la rétrospective de Cindy Sherman au MoMA ainsi que d’autres expositions plus engagées, telles que celle de Weegee à la Steven Kasher Gallery (dont la vitrine présente un mur de clichés noirs et blanc des indignés de Wall Street, pris en octobre 2011), des « Happenings » des années 60 à la Pace Gallery et enfin de l’exposition sur la Photo League au Jewish Museum. Riche d’environ 200 photographies, cette dernièresera présentée au Columbus Museum of Art (Ohio) d’avril à septembre 2012, au Contemporary Jewish Museum de San Francisco d’octobre à janvier 2013 et pour terminer au Norton Museum of Art (Floride) de février à avril 2013. -

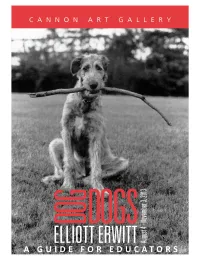

Resource Guide 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS Steps of the Three-Part-Art Gallery Education Program 2 How to Use This Resource Guide 3 Making the Most of Your Gallery Visit 4 The Artful Thinking Program 6 Curriculum Connections 7 About the Exhibition 11 About the Artist 12 A Brief History of Photography 13 Basics of Photography 17 Pre-visit activities 18 Lesson One: An Introduction to Photography 19 Lesson Two: Tell Me a Story 21 Post-visit activities 22 Lesson Three: A World of Black and White 23 Lesson Four: Frame your Viewpoint 24 Lesson Five: Headlines! 26 Glossary 28 Resources 32 Appendix 36 W ILLIAM D. C ANNON A RT G ALLERY 1 STEPS OF THE THREE-PART-ART GALLERY EDUCATION PROGRAM Resource Guide: Classroom teachers will use the preliminary lessons with students provided in the Pre-visit section of the Elliott Erwitt: Dog Dogs resource guide. On return from your field trip to the Cannon Art Gallery the classroom teacher will use Post-visit Activities to reinforce learning. The resource guide and images are provided free of charge to all classes with a confirmed reservation and are also available on our website at www.carlsbadca.gov/arts. Gallery Visit: At the gallery, an artist educator will help the students critically view and investigate original art works. Students will recognize the differences between viewing copies and seeing original artworks and learn that visiting art galleries and museums can be fun and interesting. Hands-on Art Project: An artist educator will guide the students in a hands-on art project that relates to the exhibition. -

From Pictorialism to Straight Photography

From Pictorialism to Straight photography - Photo-secession; Camera Work; 291 gallery - So focus, painterly style - labor-intensive processes: gum bichromate prinng (hand- coang arst papers with homemade emulsions) - Sacrifice detail precision for expressive effect (contrast – composion) - Symbolism (sculptor + philosopher + writer+ Edward Steichen, Rodin – The Thinker, 1902, gum bichromate print, photographer) 15 x 19 in - Composional choices + natural elements to unify pictorial whole (as opposed to labor- intensive prinng techniques) - Image metaphor for photography itself (light, shuer, print, reproDucon) - Pictorial effect Alfred Seglitz, Sun Rays, Paula, Berlin, 1889, gelan silver print, 9 x 6 in - Straight photography - Composion of abstract shapes, textures, volumes - Composion / class separaon - Polical statement? (on the subject maer but also on photography as a democrac form of art) Alfred Seglitz, The Steerage, 1907, photogravure, 335 mm / 13.19 inches x 264 mm / 10.39 inches - among the first photographic abstrac3ons to be made intenonally - Disrupon of original scale - Ambiguity of angle - does not depend upon recognizable imagery for its effect, but on the precise relaons of forms within the frame Paul,Strand, Abstracon, Twin Lakes, Conneccut, 1916, silver-planum print, 12 x 9 in. 1920s collec3ve portraiture - recovering the immediacy of experience by making the familiar seem unfamiliar (deparng from the habit of looking--and photographing-- straight ahead) - photography is mechanical and objec3ve à socially progressive - Woman-machine -

AFTER ATGET: TODD WEBB PHOTOGRAPHS NEW YORK and PARIS

e.RucSCHOELCHERanglcB'PAS a 'ihi\elU'S(k'h,iil(n e. hni • AFTER ATGET: DANTOM^79 TODD WEBB OUS PERMi T AFTER ATGET: TODD WEBB PHOTOGRAPHS NEW YORK and PARIS DIANA TUITE INTRODUCTION byBRITTSALVESEN BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART BRUNSWICK, MAINE This catalogue accompanies the COVER Fig. 26 (detail): exhibition A/Tt-rAf^ff; Todd Webb Todd Webb (American, 1905-2000) Photographs New York and Paris Rue Alesia, Paris (Oscar billboards), 1951 on view from October 28, 2011 through Vintage gelatin silver print January 29, 2012 at Bowdoin College 4x5 inches Museum of Art. Evans Gallery and Estate of Todd and Lucille Webb The exhibition and catalogue are generously supported by the PAGES 2-3 Fig. 1 (detail): Todd Webb Stevens L. Frost Endowment Fund, Harlem, NY (5 boys leaning on fence), 1946 the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Vintage gelatin silver print the Estate of Todd and Lucille Webb, 5x7 inches and Betsy Evans Hunt and Evans Gallery and Christopher Hunt. Estate of Todd and Lucille Webb Bowdoin College Museum of Art PHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS 9400 College Station Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine 04011 Brunswick, Maine, Digital Image © Pillar 207-725-3275 Digital Imaging: Figs. 4, 15, 28 © Berenice www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum Abbott / Commerce Graphics, NYC: 15, © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Designer: Katie Lee Museum of Art, New York, NY: 28 New York, New York Evans Gallery and Estate of Todd and Editor: Dale Tucker Lucille Webb, Portland, Maine © Todd Webb, Courtesy of Evans Gallery Printer: Penmor Lithographers and Estate of Todd and Lucille Webb, Lewiston, Maine Portland, Maine USA, Digital Image © Pillar Digital Imaging: Figs. -

Transatlantica, 2 | 2011 the Radical Camera, New York’S Photo League, 1936-1951 2

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 2 | 2011 Sport et société / Animals and the American Imagination The Radical Camera, New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 Jewish Museum, New York (November 4-March 25, 2012). Commissaire : Mason Klein Marie Cordié Lévy Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/5609 DOI : 10.4000/transatlantica.5609 ISSN : 1765-2766 Éditeur AFEA Référence électronique Marie Cordié Lévy, « The Radical Camera, New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 », Transatlantica [En ligne], 2 | 2011, mis en ligne le 14 mai 2012, consulté le 29 avril 2021. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/5609 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.5609 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 29 avril 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. The Radical Camera, New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 1 The Radical Camera, New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 Jewish Museum, New York (November 4-March 25, 2012). Commissaire : Mason Klein Marie Cordié Lévy 1 En ce printemps 2012 New York apparaît plus que jamais comme le lieu vivant de la photographie. En témoignent la rétrospective de Cindy Sherman au MoMA ainsi que d’autres expositions plus engagées, telles que celle de Weegee à la Steven Kasher Gallery (dont la vitrine présente un mur de clichés noirs et blanc des indignés de Wall Street, pris en octobre 2011), des « Happenings » des années 60 à la Pace Gallery et enfin de l’exposition sur la Photo League au Jewish Museum. -

Point of View Joe Constantino

Point of View Joe Constantino Straight photography or manipulation, which do you prefer? Should the image captured on film or in your digital camera be presented as taken or should you manipulate it to have it presented as you think it should be seen? The arguments for each are endless and the debate has been going on for years. The champion of straight photography, Alfred Stieglitz, who incidentally has done more to have photography accepted as a fine art than any other person, believes that the image should be presented and seen as taken. As previously indicated this is not a new issue. Many photographers manipulated their prints in the conventional darkroom with outstanding results. Probably the best in that regard was Jerry Uelsmann. If you haven’t seen his work you’re missing a wonderful experience. He used seven or eight enlargers to get the e"ect and results that he was seeking. To view some of his work go to: www.uelsmann.com His work is well worth seeing. His unique concepts have resulted in many creative images. With the advent of digital photography the manipulation of an image becomes much simpler. The taking of the picture becomes subservient to what is done with it on the computer. The emphasis is now on the computer rather than the camera. Are we headed in the right direction? The object should always be to present the image in its best possible light, pun intended. However, the balance appears to be shifting from the camera to the computer to achieve the best possible result. -

The Photographs of Frederick H. Evans

THE PHOTOGRAPHS OF FREDERICK H. EVANS I THE PHOTOGRAPHS of | Frederick H. Evans Anne M. Lyden with an essay by Hope Kingsley The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles This publication was produced to accompany Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data the exhibition A Record of Emotion: The Photographs Lyden, Anne M., 1972- of Frederick H. Evans, held at the J. Paul Getty Museum, The photographs of Frederick H. Evans / Anne M. Los Angeles, and at the National Media Museum, Lyden ; with an essay by Hope Kingsley. Bradford, England. The exhibition will be on view p. cm. in Los Angeles from February 2 to June 6,2010, and in "Produced to accompany the exhibition A record of Bradford from September 24,2010, to February 20,2011. emotion, the photographs of Frederick H. Evans, held at the J. Paul Getty Museum from February 2 to June 6, © 2010 J. Paul Getty Trust 2010." 5 4 3 2 1 Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-89236-988-1 (hardcover) Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum 1. Evans, Frederick H.—Exhibitions. 2. Architectural Getty Publications photography—Great Britain—Exhibitions. 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 3. Landscape photography—Great Britain—Exhibitions. Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 4. Photography, Artistic—Exhibitions. 1. Evans, www.getty.edu/publications Frederick H. 11. J. Paul Getty Museum, in. Title. TR647.E888 2010 Gregory M. Britton, Publisher 779'.4-dc22 Dinah Berland, Editor 2009025719 Katya Rice, Manuscript Editor Jeffrey Cohen, Designer Amita Molloy, Production Coordinator ILLUSTRATION CREDITS Jack Ross, Stacey Rain Striclder, Tricia Zigmund, All works by Frederick H. -

W. Eugene Smith Papers

W. EUGENE SMITH PAPERS Compiled by Charles Lamb and Amy Stark GUIDE SERIES NUMBER NINE CENTER FOR CREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHY UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA Center for Creative Photography University of Arizona Copyright © 1983 Arizona Board of Regents Essays by W. Eugene Smith Copyright © 1983 Heirs of W. Eugene Smith This guide was produced with the assistance of the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. Contents Introduction �A�S�� 5 The Responsibilities of the Photographic Journalist by W. Eugene Smith 7 An Essay on Music by W. Eugene Smith 10 W. Eugene Smith Papers 13 Correspondence, 1925 -78 15 Exhibition Files, ca. 1946 -79 16 Writings and Interviews 18 Photographic Essay Project Files, ca. 1938- ca. 1976 20 Activity Files, 1940s-70s 21 Organizations 21 Education 21 Sensorium Magazine 21 Grants and Miscellaneous Professional Activities 21 Financial Records , 1941-78 22 Biographical and Personal Papers, 1910-70s 23 Other Material 24 Photographic Equipment Files, ca. 1940- 70 24 Music Files, ca.1910-60s 24 Research Files, ca. 1940s- 70s 24 Miscellaneous, ca. 1950s-70s 24 Publications, ca.1937- 78 24 Personal Library 25 Portraits of W. Eugene Smith 25 W. Eugene Smith Archive: Related Materials 26 Photographs, Negatives, Transparencies 26 Audio Tapes 26 Art Work 26 Recordings 26 Cameras, Darkroom Equipment, Memorabilia 26 Photograph Collection 27 Videotapes 27 Nettie Lee Smith Photographic Materials 27 Appendix A: Selective Index to General Correspondence 28 Appendix B: List of Exhibitions 32 Appendix C: Index to Photographic Essay Projects 39 Introduction Like any other fieldof human endeavor, photography has its heroes. Legends cling to these men and women thicker and faster than the historian would wish.