EAFONSI Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traffic Volume Tables for State Highways 2018

SECTION II TRAFFIC VOLUMES ON STATE HIGHWAYS An asterisk (*) appearing to the left of a count location description indicates an Automatic Traffic Recorder (ATR) Station or Automatic Vehicle Classification (AVC) Station. See Section IV of this book for 2018 monthly traffic volumes, high hour volumes and historical trends at these stations. 29 30 2018 TRAFFIC VOLUMES ON STATE HIGHWAYS 2018 AADT All ATR Milepoint Vehicles AVC Location Description PACIFIC HIGHWAY NO. 1 Milepoint indicates distance from Oregon-California State Line 0.00 16500 At Oregon-California State Line 5.02 16500 0.30 mile south of Siskiyou Interchange Neil Creek Automatic Traffic Recorder, Sta. 15-002, 0.86 mile south of Rogue Valley Highway No. 63 11.03 16900 * Interchange (OR99) 13.67 16300 0.50 mile south of Green Springs Highway Interchange (OR66) 18.11 27900 * North Ashland Automatic Traffic Recorder, Sta. 15-021, 0.98 mile south of North Ashland Interchange 19.87 38900 0.77 mile north of North Ashland Interchange 23.90 41600 0.50 mile south of Fern Valley Road Interchange 26.91 43400 0.30 mile south of South Medford Interchange Medford Viaduct Automatic Traffic Recorder, Sta. 15-019, 1.96 miles southeast of the South Medford 28.33 54000 * Interchange 30.59 43400 0.30 mile north of Crater Lake Highway Interchange (OR62) 34.94 39400 0.50 mile south of Seven Oaks Interchange 36.04 41700 0.60 mile north of Seven Oaks Interchange Gold Hill Automatic Traffic Recorder, Sta. 15-001, 2.77 miles south of the Valley of the Rogue Bridge 42.84 40500 * Interchange 44.97 40800 0.50 mile east of Rogue River Highway (OR99), Homestead Interchange 45.61 39800 On Rogue River Bridge 48.32 39500 0.50 mile east of Rogue River Interchange 55.38 38100 0.40 mile south of East Grants Pass Interchange (US199) 57.56 28600 0.50 mile south of Redwood Highway (OR99), North Grants Pass Interchange 61.05 31900 0.40 mile south of Louse Creek Interchange Grave Creek Automatic Traffic Recorder, Sta. -

A History of Vermont

Ill Class ^:_49_ Book XlX_ Copyright]^!' COPyRlGHT DEPOSIT Thomas Chittenden The first governor of Vermont HISTORY OF VERMONT BY EDWARD DAY COLLINS, Ph.D. Formerly Instructor in History in Yale University WITH GEOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL NOTES, BIBLIOGRAPHY, CHRONOLOGY, MAPS, AND ILLUSTRATIONS BOSTON, U.S.A. GINN &L COMPANY, PUBLISHERS d)e ^tl)ensettm pregg * 1903 THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, Two CoPtcS Received OCT :9 1903 ICLAS8 A-XXc No, UC{ t ^ ^ COPY B. Copyright, 1903, by EDWARD DAY COLLINS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PREFACE The charm of romance surrounds the discovery, explo- ration, and settlement of Vermont. The early records of the state offer an exceptional field for the study of social groups placed in altogether primitive and almost isolated conditions ; while in political organization this commonwealth illustrates the development of a truly organic unity. The state was for fourteen years an independent republic, prosperous and well administered. This book is an attempt to portray the conditions of life in this state since its discovery by white men, and to indicate what the essential features of its social, eco- nomic, and political development have been. It is an attempt, furthermore, to do this in such a way as to furnish those who are placed under legal requirement to give instruction in the history of the state an oppor- tunity to comply with the spirit as well as with the letter of the law. Instruction in state history rests on a perfectly sound pedagogical and historical basis. It only demands that the same facilities be afforded in the way of texts, biblio- graphical aids, and statistical data, as are demanded in any other field of historical work, and that the most approved methods of study and teaching be followed. -

Ken Wilderness Management Plan And

GEORGE D. AIKEN WILDERNESS MANAGEMENT PLAN AND IMPLEMENTATION SCHEDULE U.S.D.A. Forest Service Green Mountain National Forest Manchester Ranger District Prepared by: \ $2- ^- Dick Andrew~,Vt. Wilderness Assoc. Date Recommended By: ^K/(^f^;^^ ~fchaelK. Schrotz +strictRanger -- - - 2 &, / ^t-^^l^L Robert Pramuk, ~ecredtionPlanner Date Approved By: >(MA&A*È. Forest Supervisor TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...............................................I Introduction Preface ....................................................3 Area Description ...........................................4 Summary of Current Situation ...............................5 Process ....................................................5 Summary of Management Recommendations ......................6 Explanation of Format ......................................6 Recreation Management Recreation Overview ........................................8 Access and Trailheads .....................................12 Trails ....................................................16 Camping ...................................................20 Pack and Saddle Animals ...................................22 Domestic Pets (Dogs)...................................... 24 Outfitters and Guides .....................................26 Information and Education .................................28 Resource Management Air .......................................................32 Water .....................................................34 Soils .....................................................36 -

Integrating the MAPS Program Into Coordinated Bird Monitoring in the Northeast (U.S

Integrating the MAPS Program into Coordinated Bird Monitoring in the Northeast (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5) A Report Submitted to the Northeast Coordinated Bird Monitoring Partnership and the American Bird Conservancy P.O. Box 249, 4249 Loudoun Avenue, The Plains, Virginia 20198 David F. DeSante, James F. Saracco, Peter Pyle, Danielle R. Kaschube, and Mary K. Chambers The Institute for Bird Populations P.O. Box 1346 Point Reyes Station, CA 94956-1346 Voice: 415-663-2050 Fax: 415-663-9482 www.birdpop.org [email protected] March 31, 2008 i TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 3 METHODS ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Collection of MAPS data.................................................................................................................... 5 Considered Species............................................................................................................................. 6 Reproductive Indices, Population Trends, and Adult Apparent Survival .......................................... 6 MAPS Target Species......................................................................................................................... 7 Priority -

Buncombe County Tax Dept. Advertisement of Tax Liens

BUNCOMBE COUNTY TAX DEPT. ADVERTISEMENT OF TAX LIENS 233 RIVERSIDE LLC 99999 EMMA RD 963889237500000 -- $4,683.85 AMERICAN IRA LLC 350 RIVERSIDE DR FBO FRANK MORRIS -- IRA 41 HUDSON LLC 974365455000000 963833557600000 $7.94 $60.00 44 WOOTEN COVE RD 41 HUDSON ST -- -- ANDERS, ROBERT S 89 WILDERNESS TRUST North Carolina General Statutes require local tax collectors 976640121900000 975478349200000 $299.41 $286.86 to advertise annually all current year unpaid taxes levied 20 MCKINNEY RD 99999 ISLAND IN THE -- SKY TRL on real estate. While we do not wish to embarrass proper- ANDERSON, DAVID -- ty owners by publishing their names in the newspaper, the LAWRENCE 952 PATTON COVE 978052158100000 ROAD LAND TRUST advertisement of property tax liens is a mandatory step in $217.43 968878409600000 1127 BEE TREE RD $125.10 the tax foreclosure process. -- 99999 PATTON COVE ANDERSON, JAMES RD 063414691300000 -- $113.00 AALTONEN, ARI TAPANI The amount due for each property reflects payments received in the 650 SHUMONT RD 977545567700000 -- $438.86 Tax Collections Department through May 19, 2021. ANDERSON, JOHN D 1603 BARNARDSVILLE 977445096600000 HWY $781.49 -- If you have questions about the names and properties appearing in this PAINT FORK RD AALTONEN, ARI TAPANI -- 977545560900000 advertisement, or want to contact us about paying your taxes, please ANDERSON, MARK $903.96 call the collections office at (828) 250-4910. Tax information is avail- ANDREW 1599 BARNARDSVILLE 962984338900000 HWY able online at: buncombecounty.org/Tax. $810.83 -- 490 GORMAN BRIDGE -

172D Infantry Regiment Argyle, NY

172d Infantry Regiment Argyle, NY. Abenaki Nation Arlington, VT. Abercrombie Expedition Armstrong, Jane B. Academies Arnold, Benedict Adams Company, Enos Arthur, Chester A. Adams, MA. Articles of Confederation. Adams, Pat Asbestos Addison County, VT Atkinson, Theodore M.T. Adirondacks Atlantic Canada Adjutant General's List, 1867 Austen House, Alice Adler, Irving Austerlitz, NY Aiken, U. S. Senator George D. Austin, Warren Robinson Airports, Vermont Aviation Albany County, NY Averill Lakes, VT Alburg, VT. Ayres, Col. H. Fairfax Aldrichville, VT Almanacs Amenia, NY American Chestnut Foundation Bailey, Consuelo Northrop American Fascist Baker, Mary A. American Revolution Baker, Nicholson Anthony, Susan B. Baker, Remember Anti-Semitism in Vermont Balloon Voyage, 1860 Appleman, Jack Band, American Legion Apsey, Rev. William Stokes Banks in Bennington Archeology in VT Banner, Bennington Architecture Barber, Noel Barber, Norton Bennington buildings misc. Barns, historic Bennington Bypass. Baro, Gene Bennington Cemeteries Barre, Vermont Bennington Club Barret, Richard Carter Bennington College Baseball Bennington County Progress Report 1998 Basin Harbor Club Bennington County Regional Plan, 1976 Bates, Archibald Bennington County Bates, Judge Edward L. Bennington Declaration for Freedom, May 1775 Battell, Joseph Bennington Historical Pageant of 1911 Battle of Bennington, eyewitness accounts Bennington Historical Society Battle of Bennington, Bach Map Bennington industry, industries Battle of Bennington, driving tour Bennington, miscellaneous Battle of Bennington, recollections Bennington Museum Battle of Bennington, rosters Bennington opera house Battle of Bennington Bennington Potters, Inc. Baum, Lt. Col. Friedrich Bennington Proprietors' records Bayley-Hazen Military Road Bennington Scale Company Becky's Stone House Bennington Town election, March 1940 Bees Bennington Township plan 1749 Belisle, Frank Bennington Trails Bellows Falls, VT. -

Appendix a Places to Visit and Natural Communities to See There

Appendix A Places to Visit and Natural Communities to See There his list of places to visit is arranged by biophysical region. Within biophysical regions, the places are listed more or less north-to-south and by county. This list T includes all the places to visit that are mentioned in the natural community profiles, plus several more to round out an exploration of each biophysical region. The list of natural communities at each site is not exhaustive; only the communities that are especially well-expressed at that site are listed. Most of the natural communities listed are easily accessible at the site, though only rarely will they be indicated on trail maps or brochures. You, the naturalist, will need to do the sleuthing to find out where they are. Use topographic maps and aerial photographs if you can get them. In a few cases you will need to do some serious bushwhacking to find the communities listed. Bring your map and compass, and enjoy! Champlain Valley Franklin County Highgate State Park, Highgate Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation Temperate Calcareous Cliff Rock River Wildlife Management Area, Highgate Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife Silver Maple-Sensitive Fern Riverine Floodplain Forest Alder Swamp Missisquoi River Delta, Swanton and Highgate Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Protected with the assistance of The Nature Conservancy Silver Maple-Sensitive Fern Riverine Floodplain Forest Lakeside Floodplain Forest Red or Silver Maple-Green Ash Swamp Pitch Pine Woodland Bog -

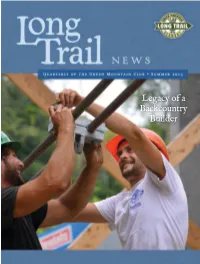

Legacy of a Backcountry Builder

Legacy of a Backcountry Builder The mission of the Green Mountain Club is to make the Vermont mountains play a larger part in the life of the people by protecting and maintaining the Long Trail System and fostering, through education, the stewardship of Vermont’s hiking trails and mountains. © BRYAN PFEIFFER, WWW.BRYANPFEIFFER.COM PFEIFFER, © BRYAN Quarterly of the River Jewelwing (Calopteryx aequabilis) damselfly Green Mountain Club c o n t e n t s Michael DeBonis, Executive Director Jocelyn Hebert, Long Trail News Editor Summer 2015, Volume 75, No. 2 Richard Andrews, Volunteer Copy Editor Brian P. Graphic Arts, Design Green Mountain Club 4711 Waterbury-Stowe Road 5 / The Visitor Center:Features A Story of Community Waterbury Center, Vermont 05677 By Maureen Davin Phone: (802) 244-7037 Fax: (802) 244-5867 6 / Legacy of a Backcountry Builder: Matt Wels E-mail: [email protected] By Jocelyn Hebert Website: www.greenmountainclub.org The Long Trail News is published by The Green Mountain Club, Inc., a nonprofit organization found- 11 / Where NOBO and SOBO Meet ed in 1910. In a 1971 Joint Resolution, the Vermont By Preston Bristow Legislature designated the Green Mountain Club the “founder, sponsor, defender and protector of the Long Trail System...” 12 / Dragons in the Air Contributions of manuscripts, photos, illustrations, By Elizabeth G. Macalaster and news are welcome from members and nonmem- bers. Copy and advertising deadlines are December 22 for the spring issue; March 22 for summer; June 22 13 / Different Places, Different Vibes: for fall; and September 22 for winter. Caretaking at Camel’s Hump and Stratton Pond The opinions expressed by LTN contributors and By Ben Amsden advertisers are not necessarily those of GMC. -

Addison Central-Western 723' 720' Adirondack Ski Center: See Alpine

69-70 70-1 71-2 72-3 Addison (Pinnacle Addison) - Addison Central-Western 723' 720' Adirondack Ski Center: See Alpine Meadows Northern 1000' 1000' 1000' 1000' Allegany State Park (Bova and Big Basin) - Red House Central-Western 190' 190' Alpine Lodge - Lake Placid Adirondacks Alpine Meadows (Adirondack Ski Center) - N. Greenfield Northern * * * * Anderlan - Little York Central-Western 350' 350' Andes Ski Center - Andes Catshills Armonk - Armonk Village SE: East of Hudson R Asech Hill - Gloversville Capital District Austerlitz Mt.: See Mountain Ten - Bald Hill - Farmingville Southern 180' 140' 140' 140' Bald Mtn.- Center Brunswick Capital District Baldpate - Crown Point Adirondacks Barton Mines - North Creek (Different from Harvey Mt.) Adirondacks Bassett Mt.: See Paleface - Bavarian Hausberg - Cairo Catskills and SE Beacon - Beacon (Small rope tow, near but separate from Dutchess) SE: East of Hudson R Bear Spring Mountain - Walton Catskills and SE Bearpen Mountain (Princeton Ski Bowl) - Prattsville Catskills and SE Beartown - Beekmantown Adirondacks Bellaire Dude Ranch (see Shayne's) Catskills Belleayre - Highmount Southern 1225' 1250' 1210' 1265' Berkshire Farm: See Darrow School - Berry School (Joe Berry School) - Binghampton Central-Western * * Bethpage - Farmingdale Southern 100' 100' 75' 100' Big Basin: See Allegany State Park - Big Bear: See Roxbury Ski Center Southern 1300' Big Birch: See Thunder Ridge Southern 675' 450' Big Rock Candy Mountain: See Rock Candy Mt. Northern 350' 300' 300' 300' Big Tupper - Tupper Lake Northern 800' -

Department of the Interior United States Geological

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MISCELLANEOUS FIELD STUDIES UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP MF-1609-C PAMPHLET MINERAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF THE LYE BROOK WILDERNESS, BENNINGTON AND WINDHAM COUNTIES, VERMONT By R. A. Ayuso, U.S. Geological Survey and D. K. Harrison, U.S. Bureau of Mines 1983 Studies Related To Wilderness Under the provisions of the Wilderness Act (Public Law 88-577, September 3, 1964) and related acts , the U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Bureau of Mines have been conducting mineral surveys of wilderness and primitive areas. Areas officially designated as "wilderness," "wild," or "canoe" when the act was passed were incorporated into the National Wilderness Preservation System, and some of them are presently being studied. The act provided that areas under consideration for wilderness designation should be studied for suitability for incorporation into the Wilderness System. The mineral surveys constitute one aspect of the suitability studies. The act directs that the results of such surveys are to be made available to the public and be submitted to the President and the Congress. This report discusses the results of a mineral survey of the Lye Brook Wilderness, Green Mountains National Forest, Bennington and Windham Counties, Vt. The area was established as a wilderness by Public Law 93-622, January 3, 1975. MINERAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL SUMMARY STATEMENT The Lye Brook Wilderness contains no significant mineral deposits. Although the Cheshire Quartzite is a potential source of low-grade silica sand and crops out in a large area within the wilderness, its degree of induration and relative inaccessibility make its use prohibitive. -

Missisquoi River Watershed Updated Water Quality and Aquatic Habitat

Missisquoi River Watershed Including Pike and Rock Rivers in Vermont Updated Water Quality and Aquatic Habitat Assessment Report August 2015 Vermont Agency of Natural Resources Department of Environmental Conservation Watershed Management Division Monitoring, Assessment, and Planning Program Table of Contents Missisquoi River Watershed ......................................................................................................... 1 General Description .................................................................................................................. 1 Missisquoi River .................................................................................................................... 1 Rock River ............................................................................................................................. 1 Pike River .............................................................................................................................. 2 Earlier Information on the Rivers within this Report .................................................................. 2 Missisquoi River Basin Association sampling ........................................................................ 2 Upper Missisquoi River ................................................................................................................. 3 General Description .................................................................................................................. 3 Upper Missisquoi River and Tributaries Summary -

Green Mountain National Forest Wilderness Interpretation And

Wilderness Interpretation & Education Plan Green Mountain National Forest Approved by: __/s/ Jerri Marr - March 2010________________ Acting Forest Supervisor Jerri Marr Reviewed by: __/s/ Chad VanOrmer – 3/12/10______________ Heritage, Recreation, and Wildernesss Program Manager Chad VanOrmer Prepared by: Recreation Planner Douglas Reeves . 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Goals and Objectives 3 3. Historical Perspective 4 4. The 1964 Wilderness Act 5 5. Wilderness Areas on the Green Mountain National Forest 6 6. FSM 2300 – Wilderness References 7 7. The 10 Year Wilderness Stewardship Challenge 10 8. Green Mountain National Forest Program of Work 16 9. Wilderness Leave No Trace Principles 17 10. Identification of General and Specific Audiences 21 11. Targeted I&E Messages 22 3 . 1 - Introduction “I believe that at least in the present phase of our civilization we have a profound, a fundamental need for areas of wilderness – a need that is not only recreational and spiritual but also educational and scientific, and withal essential to a true understanding of ourselves, our culture, our own natures, and our place in all nature. By very definition, this wilderness is a need. The idea of wilderness as an area without man’s influence is man’s own concept. Its values are human values. Its preservation is a purpose that arises out of man’s own sense of his fundamental needs.” -- Howard Zahniser (Author of the Wilderness Act), from The Need for Wilderness Areas “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen.