Adam Smith, Radical and Egalitarian in Memoriam John Anderson Mclean (1915-2001) Adam Smith, Radical and Egalitarian an Interpretation for the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Queensferry and Inverkeithing (Potentially Vulnerable Area 10/10)

North Queensferry and Inverkeithing (Potentially Vulnerable Area 10/10) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Forth Estuary Fife Council South Fife coastal Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impacts flooding of Summary At risk of flooding • 40 residential properties • 30 non-residential properties • £590,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection management warning -

FONNA FORMAN Associate Professor, Department of Political Science

FONNA FORMAN Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Founding Co-Director, UCSD Center on Global Justice Founding Co-Director, UCSD / Blum Cross-Border Initiative University of California, San Diego UCSD Center on Global Justice 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, CA 92093-0521 858 822-3868 [email protected] November 2015 Bio Fonna Forman is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of California San Diego, founding co-director of the UCSD Center on Global Justice and the UCSD / BLUM Cross- Border Initiative. She is a political theorist best known for her revisionist work on Adam Smith, recuperating the ethical, spatial, social, public and urban dimensions of his political economy. Current work focuses on theories and practices of global justice as they manifest at local and regional scales, and the role of civic participation in strategies of equitable urbanization. Present sites of investigation include Bogota and Medellín, Colombia; Ukraine; the Palestinian territories; and the San Diego-Tijuana border region. Forman has just completed a volume of collected essays (with Amartya Sen) on critical interventions in global justice theory, and papers on ‘municipal cosmopolitanism’ and “political leadership in Latin America’. She is presently writing a book on Adam Smith in Latin America. She is co-investigating with Teddy Cruz a Ford Foundation-funded study of citizenship culture in the San Diego-Tijuana border region, in collaboration with the Bogota-based NGO, Corpovisionarios. She is Vice-Chair of the University of California Climate Solutions Group and co-editor of Bending the Curve: 10 Scalable Solutions for Carbon and Climate Neutrality (The University of California report on carbon neutrality). -

Tayside November 2014

Regional Skills Assessment Tayside November 2014 Angus Perth and Kinross Dundee City Acknowledgement The Regional Skills Assessment Steering Group (Skills Development Scotland, Scottish Enterprise, the Scottish Funding Council and the Scottish Local Authorities Economic Development Group) would like to thank SQW for their highly professional support in the analysis and collation of the data that forms the basis of this Regional Skills Assessment. Regional Skills Assessment Tayside Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Context 5 3 Economic Performance 7 4 Profile of the Workforce 20 5 People and Skills Supply 29 6 Education and Training Provision 43 7 Skills Mismatches 63 8 Economic and Skills Outlook 73 9 Questions Arising 80 sds.co.uk 1 Regional Skills Assessment Section 1 Tayside Introduction 1 Introduction 1.1 The purpose of Regional Skills Assessments This document is one of a series of Regional Skills Assessments (RSAs), which have been produced to provide a high quality and consistent source of evidence about economic and skills performance and delivery at a regional level. The RSAs are intended as a resource that can be used to identify regional strengths and any issues or mismatches arising, and so inform thinking about future planning and investment at a regional level. 1.2 The development and coverage of RSAs The content and geographical coverage of the RSAs was decided by a steering group comprising Skills Development Scotland, Scottish Enterprise, the Scottish Funding Council and extended to include the Scottish Local Authorities Economic Development Group during the development process. It was influenced by a series of discussions with local authorities and colleges, primarily about the most appropriate geographic breakdown. -

Coasts and Seas of the United Kingdom. Region 4 South-East Scotland: Montrose to Eyemouth

Coasts and seas of the United Kingdom Region 4 South-east Scotland: Montrose to Eyemouth edited by J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson, S.S. Kaznowska, J.P. Doody, N.C. Davidson & A.L. Buck Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House, City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY UK ©JNCC 1997 This volume has been produced by the Coastal Directories Project of the JNCC on behalf of the project Steering Group. JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team Project directors Dr J.P. Doody, Dr N.C. Davidson Project management and co-ordination J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson Editing and publication S.S. Kaznowska, A.L. Buck, R.M. Sumerling Administration & editorial assistance J. Plaza, P.A. Smith, N.M. Stevenson The project receives guidance from a Steering Group which has more than 200 members. More detailed information and advice comes from the members of the Core Steering Group, which is composed as follows: Dr J.M. Baxter Scottish Natural Heritage R.J. Bleakley Department of the Environment, Northern Ireland R. Bradley The Association of Sea Fisheries Committees of England and Wales Dr J.P. Doody Joint Nature Conservation Committee B. Empson Environment Agency C. Gilbert Kent County Council & National Coasts and Estuaries Advisory Group N. Hailey English Nature Dr K. Hiscock Joint Nature Conservation Committee Prof. S.J. Lockwood Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Sciences C.R. Macduff-Duncan Esso UK (on behalf of the UK Offshore Operators Association) Dr D.J. Murison Scottish Office Agriculture, Environment & Fisheries Department Dr H.J. Prosser Welsh Office Dr J.S. Pullen WWF-UK (Worldwide Fund for Nature) Dr P.C. -

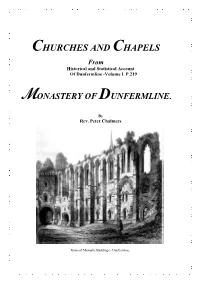

Churches and Chapels Monastery

CHURCHES AND CHAPELS From Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline -Volume I. P.219 MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE. By Rev. Peter Chalmers Ruins of Monastic Buildings - Dunfermline. A REPRINT ON DISC 2013 ISBN 978-1-909634-03-9 CHURCHES AND CHAPELS OF THE MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE FROM Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline Volume I. P.219 By Rev. Peter Chalmers, A.M. Minister of the First Charge, Abbey Church DUNFERMLINE. William Blackwood and Sons Edinburgh MDCCCXLIV Pitcairn Publications. The Genealogy Clinic, 18 Chalmers Street, Dunfermline KY12 8DF Tel: 01383 739344 Email enquiries @pitcairnresearh.com 2 CHURCHES AND CHAPELS OF THE MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE. From Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline Volume I. P.219 By Rev. Peter Chalmers The following is an Alphabetical List of all the Churches and Chapels, the patronage which belonged to the Monastery of Dunfermline, along, generally, with a right to the teinds and lands pertaining to them. The names of the donors, too, and the dates of the donation, are given, so far as these can be ascertained. Exact accuracy, however, as to these is unattainable, as the fact of the donation is often mentioned, only in a charter of confirmation, and there left quite general: - No. Names of Churches and Chapels. Donors. Dates. 1. Abercrombie (Crombie) King Malcolm IV 1153-1163. Chapel, Torryburn, Fife 11. Abercrombie Church Malcolm, 7th Earl of Fife. 1203-1214. 111 . Bendachin (Bendothy) …………………………. Before 1219. Perthshire……………. …………………………. IV. Calder (Kaledour) Edin- Duncan 5th Earl of Fife burghshire ……… and Ela, his Countess ……..1154. V. Carnbee, Fife ……….. ………………………… ……...1561 VI. Cleish Church or……. Malcolm 7th Earl of Fife. -

Regional Skills Assessment Fife November 2014

Regional Skills Assessment Fife November 2014 Fife Acknowledgement The Regional Skills Assessment Steering Group (Skills Development Scotland, Scottish Enterprise, the Scottish Funding Council and the Scottish Local Authorities Economic Development Group) would like to thank SQW for their highly professional support in the analysis and collation of the data that forms the basis of this Regional Skills Assessment. Regional Skills Assessment Fife Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Context 5 3 Economic Performance 7 4 Profile of the Workforce 20 5 People and Skills Supply 28 6 Education and Training Provision 41 7 Skills Mismatches 62 8 Employment and Skills Outlook 71 9 Questions Arising 78 sds.co.uk 1 Regional Skills Assessment Section 1 Fife Introduction 1 Introduction 1.1 The purpose of Regional Skills Assessments This document is one of a series of Regional Skills Assessments (RSAs), which have been produced to provide a high quality and consistent source of evidence about economic and skills performance and delivery at a regional level. The RSAs are intended as a resource that can be used to identify regional strengths and any issues or mismatches arising, and so inform thinking about future planning and investment at a regional level. 1.2 The development and coverage of RSAs The content and geographical coverage of the RSAs was decided by a steering group comprising Skills Development Scotland, Scottish Enterprise, the Scottish Funding Council and extended to include the Scottish Local Authorities Economic Development Group during the development process. It was influenced by a series of discussions with local authorities and colleges, primarily about the most appropriate geographic breakdown. -

Pdf Colleges Scotland Keyfacts 2013

What Colleges Deliver Colleges provided learning for over 250,000 students last year. While numbers overall have fallen, there has been an increased proportion of students doing full-time courses, and an increase in the proportion of higher education delivered. Number of Students FE/HE Split Mode of How Learning Colleges FE HE FT PT are Funded Colleges receive a signicant amount of public funding, distributed by the Scoish Funding Council (SFC). Approximately 25% of income is earned by other means. 2012-13 saw the introduction of a funding stream directly from the Skills Development Scotland (SDS) for the New • 16-24 year olds accounted for 70% of all hours of College Learning Programme. learning in 2011-12 • 63% of college students have no qualification on entry • 27% of all school leavers go into further education College Learners Top 10 Subject Areas Widening Access College Sta Colleges are the most accessible route into learning for To keep skills up-to-date, those in deprived communities or with additional needs, colleges oen recruit sta with oering an invaluable route to gaining skills, improving industry experience or look to employability or gaining a higher education. have sta seconded back into industry to ensure students are • 28% of students in colleges are from beneting from current practice. Scotland’s most deprived postcodes • During 2011-12, 3,200 students with an HND/C • 5,306 teaching sta articulated into 2nd or 3rd year full-time rst degree in colleges courses • 70% of teaching sta • 5% of all hours of learning (4.3 -

The Fife Pilgrim

PILGRIMAGE The Fife From the 11th – 16th centuries, Fife attracted pilgrims from across Europe to the shrines of St. Andrew and St. Margaret. They followed their faith, in search of miracles, cures, Pilgrim Way forgiveness and adventure. A network of ferries, bridges, wells, chapels and accommodation was built to facilitate the Discover Scotland's safe passage of the pilgrims. Get away from it all and enjoy the fresh air and exercise by Pilgrim Kingdom becoming a modern day pilgrim. Undertake an inspiring journey by walking the ancient pathways, visit the medieval sites along the route and uncover Fife’s forgotten pilgrim stories. As in medieval times, you will find a choice of shelter Pilgrims journeying to St. Andrews and hospitality, whilst enjoying the kindness of strangers you Crown Copyright HES meet along the way. GET INVOLVED Work to improve the existing network of paths and construct new sections began in summer 2017 and will be complete soon. You then will be able to download a detailed map from our website and walk the route. In the interests of your safety and the working landscape, please resist trying to find the route before the map is published. A range of Interpretation proposals are under development and will be complete by March 2019, when the route will be officially launched. Get involved in the project by volunteering or taking part in an exciting free programme of talks, guided walks, an archaeological dig and much more! See website for details www.fifecoastandcountrysidetrust.co.uk FUNDERS Fife Coast and Countryside -

Obarski Family

The Last Shop in Earlsferry This article is based on a talk about the Obarski Family given by Irene Stevenson to the Elie and Earlsferry History Society on 13 February 2020 (the difference in the name Obarski and Obarska is explained by Polish convention of female surnames ending in …ska when the male form is …ski). I have been asked to give a talk on the village experiences of the Obarski family. This will be mainly about ‘Henry and Elsie’ as most people in Elie and Earlsferry will remember them. My name is Irene Stevenson. My Maiden name was Urquhart and Henry was my step-father, my mother’s second husband. I realise that quite a lot of people do not know that, and it is a credit to my family that I was recognised to be very much part of the Obarski family. I think I still qualify as the only person to give this talk! Below are some photographs and will be how most will remember Henry and Elsie. Henry came here during the war and like many others, he never talked about his war experiences. I do know that he was involved in Operation Market Garden at Arnhem. I have read much about this but I am not here to give a talk on Arnhem. If you have seen the film “A Bridge Too Far” or read the book, you will know about the awful things that happened there. I was well aware that he did suffer terribly from shell-shock. We had to be so careful not to make sudden noises, bang doors, etc. -

74810 Sav the Hermitage.Indd

THE HERMITAGE LadywaLk • anstruther • FiFe • ky10 3EH THE HERMITAGE ladywalk • anStrutHer • fife • ky10 3eH Historic house within Anstruther conservation area with lovely garden and sea views overlooking the East Neuk coast St Andrews 9.5 miles, Dundee 24 miles, Edinburgh 49 miles = Hall, library, kitchen, dining room, pantry & utility room, cloakroom, office, shower room, sitting room, playroom Drawing room, master bedroom with dressing room (bedroom 6) and en suite bathroom. Guest bedroom Three further bedrooms, family bathroom In and out garage and additional off street parking Outbuildings Garden EPC Rating = D Your attention is drawn to the important notice on the last page of the text Savills Perth Earn House, Broxden Business Park Lamberkine Drive Perth PH2 8EH Tel: 01738 477525 Fax: 01738 448899 [email protected] VIEWING Strictly by appointment with Savills - 0131 247 3738. SITUATION The Hermitage, with its large garden, sits in a secluded setting in the centre of Anstruther. It has superb proximity for the beach, harbour and town services yet is in an enviable position set away from the main thoroughfares. The East Neuk of Fife is renowned for being one of the driest and sunniest parts of Scotland. It boasts a number of fishing villages built around picturesque harbours, sandy unspoilt beaches and rich farmland. The town of Anstruther has a vibrant community. It has a working harbour, is home to the local RNLI, and has excellent facilities for pleasure boats. It has a good range of independent retailers and some highly regarded restaurants, a large supermarket as well as primary and secondary schooling. -

II IAML Annual Conference

IAML Annual Conference Edinburgh II 6 - I I August 2000 International Association of Music Libraries,Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML) Association Internationale des Bibliothèques,Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux (AIBM) Internationale Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdokumentationszentren (IVBM) Contents 3 Introduction: English 13 Einleitung: Deutsch 23 Introduction: Français 36 Conference Programme 51 IAML Directory 54 IAML(UK) Branch 59 Sponsors IAML Annual Conference The University of Edinburgh Edinburgh, Scotland 6 - I I August 2000 International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML) Association Internationale des Bibliothèques,Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux (AIBM) Internationale Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdokumentationszentren (IVBM) oto: John Batten Without the availability of music libraries, I would never have got to know musical scores. They are absolutely essential for the furtherance of musical knowledge and enjoyment. It is with great pleasure therefore that I lend my support to the prestigious conference of IAML which is being hosted by the United Kingdom Branch in Edinburgh. I am delighted as its official patron to commend the 2000 IAML international conference of music librarians' Sir Peter Maxwell Davies Patron: IAML2000 5 II Welcome to Edinburgh Contents We have great pleasure in welcoming you to join us in the 6 Conference Information beautiful city of Edinburgh for the 2000 IAML Conference. 7 Social Programme Events during the week will take place in some of the 36 Conference Programme city's magnificent buildings and Wednesday afternoon tours 5I IAML Directory are based on the rich history of Scotland.The Conference 54 IAML(UK) Branch sessions as usual provide a wide range of information to 59 Sponsors interest librarians from all kinds of library; music is an international language and we can all learn from the experiences of colleagues. -

Scotland Malawi Partnership (SMP)

Scottish Government Scotland Malawi Partnership End of Year Report This narrative report should be submitted together with your updated logframe and completed budget spreadsheet. PLEASE READ ATTACHED GUIDELINES BEFORE COMPLETING THE FOR 1. Basic Information Complete the information below for management purposes. Please indicate in the relevant section whether any changes to your basic information (e.g. budget) have occurred during this reporting year. Explanations should be provided in section 3. 1.1 Reporting Year From: April 2017 To: March 2018 1.2 Grant Year (e.g. Year 1) Year 1 1.3 Total Budget £251,131 for 2017/18 1.4 Total Funding from ID £251,131 for 2017/18; £236,861 for 2018/19; £242,536 for 2019/20. A total three-year grant of £730,528 1.5 Supporting Documentation Proposed Revised Logical Framework/business Check box to confirm key plan, if applicable documents have been submitted with this report Please list any further Other, please detail: supporting documentation (1) 2017-18 Member Impact Statements that has been submitted (2) Membership Needs and Impact Survey 2018 Summary of Results (3) Buy Malawian 2018 Campaign Report final (4) Summary of 2017 AGM Feedback (5) 2018 Scotland-Malawi Partnership Youth Congress Report (6) Report on 2017 Malawi Development Programme SMP strand meetings (7) 2017 Strand Meetings WhatsApp Q&A Consolidated (8) Lobbying and Advocacy Report 2017-18 (9) Agriculture 2017-18 Progress and Impact report (10) BITT 2017 18 Progress and Impact report (11) Youth and Schools 2017 18 Progress and Impact report 1.6 Response to Previous Scottish Government’s Action taken since the Progress Reviews comments on previous last report: reports (state which report) 1.7 Date report produced 15th May 2018 (two week extension agreed) 1.8 Name and position of [redacted].