Are Condorcet and Minimax Voting Systems the Best?1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Are Condorcet and Minimax Voting Systems the Best?1

1 Are Condorcet and Minimax Voting Systems the Best?1 Richard B. Darlington Cornell University Abstract For decades, the minimax voting system was well known to experts on voting systems, but was not widely considered to be one of the best systems. But in recent years, two important experts, Nicolaus Tideman and Andrew Myers, have both recognized minimax as one of the best systems. I agree with that. This paper presents my own reasons for preferring minimax. The paper explicitly discusses about 20 systems. Comments invited. [email protected] Copyright Richard B. Darlington May be distributed free for non-commercial purposes Keywords Voting system Condorcet Minimax 1. Many thanks to Nicolaus Tideman, Andrew Myers, Sharon Weinberg, Eduardo Marchena, my wife Betsy Darlington, and my daughter Lois Darlington, all of whom contributed many valuable suggestions. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction and summary 3 2. The variety of voting systems 4 3. Some electoral criteria violated by minimax’s competitors 6 Monotonicity 7 Strategic voting 7 Completeness 7 Simplicity 8 Ease of voting 8 Resistance to vote-splitting and spoiling 8 Straddling 8 Condorcet consistency (CC) 8 4. Dismissing eight criteria violated by minimax 9 4.1 The absolute loser, Condorcet loser, and preference inversion criteria 9 4.2 Three anti-manipulation criteria 10 4.3 SCC/IIA 11 4.4 Multiple districts 12 5. Simulation studies on voting systems 13 5.1. Why our computer simulations use spatial models of voter behavior 13 5.2 Four computer simulations 15 5.2.1 Features and purposes of the studies 15 5.2.2 Further description of the studies 16 5.2.3 Results and discussion 18 6. -

On the Distortion of Voting with Multiple Representative Candidates∗

The Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-18) On the Distortion of Voting with Multiple Representative Candidates∗ Yu Cheng Shaddin Dughmi David Kempe Duke University University of Southern California University of Southern California Abstract voters and the chosen candidate in a suitable metric space (Anshelevich 2016; Anshelevich, Bhardwaj, and Postl 2015; We study positional voting rules when candidates and voters Anshelevich and Postl 2016; Goel, Krishnaswamy, and Mu- are embedded in a common metric space, and cardinal pref- erences are naturally given by distances in the metric space. nagala 2017). The underlying assumption is that the closer In a positional voting rule, each candidate receives a score a candidate is to a voter, the more similar their positions on from each ballot based on the ballot’s rank order; the candi- key questions are. Because proximity implies that the voter date with the highest total score wins the election. The cost would benefit from the candidate’s election, voters will rank of a candidate is his sum of distances to all voters, and the candidates by increasing distance, a model known as single- distortion of an election is the ratio between the cost of the peaked preferences (Black 1948; Downs 1957; Black 1958; elected candidate and the cost of the optimum candidate. We Moulin 1980; Merrill and Grofman 1999; Barbera,` Gul, consider the case when candidates are representative of the and Stacchetti 1993; Richards, Richards, and McKay 1998; population, in the sense that they are drawn i.i.d. from the Barbera` 2001). population of the voters, and analyze the expected distortion Even in the absence of strategic voting, voting systems of positional voting rules. -

April 7, 2021 To: Representative Mark Meek, Chair House Special

The League of Women Voters of Oregon is a 101-year-old grassroots nonpartisan political organization that encourages informed and active participation in government. We envision informed Oregonians participating in a fully accessible, responsive, and transparent government to achieve the common good. LWVOR Legislative Action is based on advocacy positions formed through studies and member consensus. The League never supports or opposes any candidate or political party. April 7, 2021 To: Representative Mark Meek, Chair House Special Committee On Modernizing the People’s Legislature Re: Hearing on Ranked Choice Voting Chair Meek, Vice-Chair Wallan and committee members, The League of Women Voters (LWV) at the national and state levels has long been interested in electoral system reforms as a way to achieve the greatest level of representation. In Oregon, we most recently conducted an in-depth two-year study (2016) to update our Election Methods Position. That position was (in part) the basis for a similar update to the LWV United States position in 2020. In League studies around the nation, our current system (called either ‘plurality’ or ‘First Past the Post’) where ‘whoever gets the most votes wins’ has been found the least-desirable of all electoral systems. The Oregon position is no different. It further lays out criteria for best systems; and states our support of Ranked Choice Voting (RCV). Several of the related criteria are: • Encouraging voter participation and voter engagement. • Encouraging those with minority opinions to participate. • Promote sincere voting over strategic voting. • Discourage negative campaigning. For multi-seat elections (a.k.a. at-large or multi-winner elections), the LWV Oregon position currently supports several systems. -

Vote Splitting

Vote Splitting: Who benefits from better The Root of Electoral Evils voting methods? Our current choose-one Plurality Voting method allows voters to express an opinion about only one candidate. This works fine—when there are only two candidates. Add a third, and you get vote splitting: the most similar candidates split their common supporters’ votes, and can lose to another less preferred Major-party supporters candidate—possibly even the least preferred! • Better primaries, without vote The Vote-Splitting Cycle What Makes a Good Voting Method splitting and spoilers A good voting method has several essential Fear of being a “spoiler” deters many candidates • Less negative campaigning, qualities, starting with the fundamental two: from entering the race, denying voters a real choice. more post-primary unity Often enough more candidates run anyway, forcing Accuracy and Simplicity. Over the expected voters to play a game: guessing how other voters range of election scenarios, the voting method • No minor-party spoilers will vote. For this they consider candidates’ “viabilty” must produce results that accurately reflect the — not only their qualifications, but their popularity, will of the electorate, at an acceptable logistical Minor-party supporters funding, and media support. Campaign money cost. To produce such results, we need three more becomes necessary not just to make candidates qualities: Expressiveness, Sincerity, and Equality. • Other parties see minor-party candidates as allies, not spoilers known, but to signal that they are serious. Facing Voters must be able and willing to express a the “wasted-vote dilemma,” many voters abandon reasonably full and sincere opinion, and the • Results reflect a party’s true their favorite candidates for the few who seem to presence of similar candidates should not hurt or support have the best chances — the bandwagon effect. -

Consistent Approval-Based Multi-Winner Rules

Consistent Approval-Based Multi-Winner Rules Martin Lackner Piotr Skowron TU Wien University of Warsaw Vienna, Austria Warsaw, Poland Abstract This paper is an axiomatic study of consistent approval-based multi-winner rules, i.e., voting rules that select a fixed-size group of candidates based on approval bal- lots. We introduce the class of counting rules, provide an axiomatic characterization of this class and, in particular, show that counting rules are consistent. Building upon this result, we axiomatically characterize three important consistent multi- winner rules: Proportional Approval Voting, Multi-Winner Approval Voting and the Approval Chamberlin–Courant rule. Our results demonstrate the variety of multi- winner rules and illustrate three different, orthogonal principles that multi-winner voting rules may represent: individual excellence, diversity, and proportionality. Keywords: voting, axiomatic characterizations, approval voting, multi-winner elections, dichotomous preferences, apportionment 1 Introduction In Arrow’s foundational book “Social Choice and Individual Values” [5], voting rules rank candidates according to their social merit and, if desired, this ranking can be used to select the best candidate(s). As these rules are concerned with “mutually exclusive” candidates, they can be seen as single-winner rules. In contrast, the goal of multi-winner rules is to select the best group of candidates of a given size; we call such a fixed-size set of candidates a committee. Multi-winner elections are of importance in a wide range of scenarios, which often fit in, but are not limited to, one of the following three categories [25, 29]. The first category contains multi-winner elections aiming for proportional representation. -

Voting Rights Plan

Making Virginia Number One in the Nation for Voting Rights Summary Protecting the fundamental voting rights of Virginians is personal for Jenn McClellan. In 1901, when her great-grandfather Henry Davidson went to register to vote in Bibb County, Alabama, he was sub- jected to a challenging literacy test and ordered to find three white men to vouch for his character. Her great-grandmother was not even allowed to register to vote. Recently, Jenn found her father James McClellan’s poll tax receipt. That moment – coupled with the recent attempts by Republican state legis- latures across the country to restrict voting rights affirmed the on-going struggle for fair access and the urgent need to protect voting rights. A copy of the 1947 poll tax that Jenn McClellan’s father paid in Davidson County, TN. In Jenn’s 16 sessions in the legislature, she has driven and fought for generational progress in voter protections and rights. She helped reverse the GOP leader’s restrictive voter ID requirements in 2010 and seven restrictive Republican voter ID laws from 2013, expanded the list of accepted voter ID options, helped create no excuse absentee voting, extended the timeline for mailed absentee ballots, enabled permanent absentee voting by mail, created automatic voter registration and same day registration, and ended prison gerrymandering in the redistricting process. Jenn’s leadership in the Virginia General Assembly laid the foundation for generational progress in protecting Virginians’ right to vote. In 2021, Jenn passed the Voting Rights Act of Virginia. The Voting Rights Act of Virginia is modeled after the feder- al Voting Rights Act of 1965 and will protect all voters in the Commonwealth from suppression, discrim- ination and intimidation, and expand language access to voters for whom English is a second language. -

Improving Elections with Instant Runoff Voting

FAIRVOTE: THE CENTER FOR VOTING & DEMOCRACY | WWW.FAIRVOTE.ORG | (301) 270-4616 Improving Elections with Instant Runoff Voting Instant Runoff Voting (IRV) - Used for both government and private elections around the United States and the world, instant runoff voting is a simple election process used to avoid the expense, difficulties and shortcomings of runoff elections. Compared to the traditional “delayed” runoff, IRV saves taxpayers money, cuts the costs of running campaigns, elects public officials with higher voter turnout and encourages candidates to run less negative campaigns. How instant runoff voting works: • First round of counting: The voters rank their preferred candidate first and may also rank additional choices (second, third, etc.). In the first round of counting, the voters’ #1 choices are tallied. A candidate who receives enough first choices to win outright (typically a majority) is declared the winner. However, other candidates may have enough support to require a runoff – just as in traditional runoff systems. • Second round: If no one achieves a clear victory, the runoff occurs instantly. The candidate with the fewest votes is removed and the votes made for that candidate are redistributed using voters’ second choices. Other voters’ top choices remain the same. The redistributed votes are added to the counts of the candidates still in competition. The process is repeated until one candidate has majority support. The benefits: Instant runoff voting (IRV) would do everything the current runoff system does to ensure that the winner has popular support – but it does it in one election rather than two. • Saves localities, taxpayers and candidates money by holding only one election. -

THE POLITICS of ELECTORAL REFORM Changing the Rules of Democracy

THE POLITICS OF ELECTORAL REFORM Changing the Rules of Democracy Elections lie at the heart of democracy, and this book seeks to understand how the rules governing those elections are chosen. Drawing on both broad comparisons and detailed case studies, it focuses upon the electoral rules that govern what sorts of preferences voters can express and how votes translate into seats in a legislature. Through detailed examination of electoral reform politics in four countries (France, Italy, Japan, and New Zealand), Alan Renwick shows how major electoral system changes in established democracies occur through two contrasting types of reform process. Renwick rejects the simple view that electoral systems always straightforwardly reflecttheinterestsofthepoliticiansinpower. Politicians’ motivations are complex; politicians are sometimes unable to pursue reforms they want; occasionally, they are forced to accept reforms they oppose. The Politics of Electoral Reform shows how voters and reform activists can have real power over electoral reform. alan renwick is a lecturer in Comparative Politics at the University of Reading. THE POLITICS OF ELECTORAL REFORM Changing the Rules of Democracy ALAN RENWICK School of Politics and International Relations University of Reading cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521765305 © Alan Renwick 2010 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

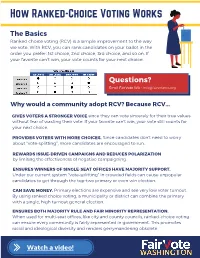

V3 0.9 How RCV Works 1-Pager

How Ranked-Choice Voting Works The Basics Ranked choice voting (RCV) is a simple improvement to the way we vote. With RCV, you can rank candidates on your ballot in the order you prefer: 1st choice, 2nd choice, 3rd choice, and so on. If your favorite can’t win, your vote counts for your next choice. Questions? Email FairVote WA - [email protected] Why would a community adopt RCV? Because RCV... G I V E S V O T E R S A S T R O N G E R V O I C E since they can vote sincerely for their true values without fear of wasting their vote. If your favorite canʼt win, your vote still counts for your next choice. P R O V I D E S V O T E R S W I T H M O R E C H O I C E S . Since candidates donʼt need to worry about “vote-splitting”, more candidates are encouraged to run. REWARDS ISSUE-DRIVEN CAMPAIGNS AND REDUCES POLARIZATION by limiting the effectiveness of negative campaigning. ENSURES WINNERS OF SINGLE-SEAT OFFICES HAVE MAJORITY SUPPORT. Under our current system “vote-splitting” in crowded fields can cause unpopular candidates to get through the top-two primary or even win election. C A N S A V E M O N E Y . Primary elections are expensive and see very low voter turnout. By using ranked choice voting, a municipality or district can combine the primary with a single, high turnout general election. ENSURES BOTH MAJORITY RULE AND FAIR MINORITY REPRESENTATION. -

General Conference, Universität Hamburg, 22 – 25 August 2018

NEW OPEN POLITICAL ACCESS JOURNAL RESEARCH FOR 2018 ECPR General Conference, Universität Hamburg, 22 – 25 August 2018 EXCHANGE EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Alexandra Segerberg, Stockholm University, Sweden Simona Guerra, University of Leicester, UK Published in partnership with ECPR, PRX is a gold open access journal seeking to advance research, innovation and debate PRX across the breadth of political science. NO ARTICLE PUBLISHING CHARGES THROUGHOUT 2018–2019 General Conference bit.ly/introducing-PRX 22 – 25 August 2018 General Conference Universität Hamburg, 22 – 25 August 2018 Contents Welcome from the local organisers ........................................................................................ 2 Mayor’s welcome ..................................................................................................................... 3 Welcome from the Academic Convenors ............................................................................ 4 The European Consortium for Political Research ................................................................... 5 ECPR governance ..................................................................................................................... 6 ECPR Council .............................................................................................................................. 6 Executive Committee ................................................................................................................ 7 ECPR staff attending ................................................................................................................. -

Electoral Institutions, Party Strategies, Candidate Attributes, and the Incumbency Advantage

Electoral Institutions, Party Strategies, Candidate Attributes, and the Incumbency Advantage The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Llaudet, Elena. 2014. Electoral Institutions, Party Strategies, Candidate Attributes, and the Incumbency Advantage. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12274468 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Electoral Institutions, Party Strategies, Candidate Attributes, and the Incumbency Advantage A dissertation presented by Elena Llaudet to the Department of Government in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Political Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2014 ⃝c 2014 - Elena Llaudet All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Stephen Ansolabehere Elena Llaudet Electoral Institutions, Party Strategies, Candidate Attributes, and the Incumbency Advantage Abstract In developed democracies, incumbents are consistently found to have an electoral advantage over their challengers. The normative implications of this phenomenon depend on its sources. Despite a large existing literature, there is little consensus on what the sources are. In this three-paper dissertation, I find that both electoral institutions and the parties behind the incumbents appear to have a larger role than the literature has given them credit for, and that in the U.S. context, between 30 and 40 percent of the incumbents' advantage is driven by their \scaring off” serious opposition. -

Perspective Chaos, but in Voting and Apportionments?

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 96, pp. 10568–10571, September 1999 Perspective Chaos, but in voting and apportionments? Donald G. Saari* Department of Mathematics, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208-2730 Mathematical chaos and related concepts are used to explain and resolve issues ranging from voting paradoxes to the apportioning of congressional seats. Although the phrase ‘‘chaos in voting’’ may suggest the complex- A wins with the plurality vote (1, 0, 0, 0), B wins by voting ity of political interactions, here I indicate how ‘‘mathematical for two candidates, that is, with (1, 1, 0, 0), C wins by voting chaos’’ helps resolve perplexing theoretical issues identified as for three candidates, and D wins with the method proposed by early as 1770, when J. C. Borda (1) worried whether the way the Borda, now called the Borda Count (BC), where the weights French Academy of Sciences elected members caused inappro- are (3, 2, 1, 0). Namely, election outcomes can more accurately priate outcomes. The procedure used by the academy was the reflect the choice of a procedure rather than the voters’ widely used plurality system, where each voter votes for one preferences. This aberration raises the realistic worry that candidate. To illustrate the kind of difficulties that can arise in this inadvertently we may not select whom we really want. system, suppose 30 voters rank the alternatives A, B, C, and D as ‘‘Bad decisions’’ extend into, say, engineering, where one follows (where ‘‘՝’’ means ‘‘strictly preferred’’): way to decide among design (material, etc.) alternatives is to assign points to alternatives based on how they rank over Table 1.