Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Arms on the Chaucer Tomb at Ewelme with a Note on the Early Manorial History

The Arms on the Chaucer Tomb at Ewelme with a note on the early manorial history . of the parish by E. A. GREENING LAMBORN ALTHOUGH representing one of the largest and most interesting collec ..r-\. tions of mediaeval coats to be found on any tomb in England, the arms on the Chaucer tomb at Ewelme have never been competently examined, so that the persons represented by them have been only partially, and sometimes incorrectly, identified. The most recent account of them, in the otherwise admirable notes on the church compiled by a late rector, is of little genealogical or heraldic value; and the account in the first volume of the Oxford Journal of Monumental Brasses is of no value at all : , Others to some faint meaning make pretence But Shadwell never deviates into sense.' its author's competence may be judged by his description of ' time-honoured Lancaster' as ' the Duke of Gaunt.' Sir Harris Nicolas, who wrote the Memoir prefixed to the Aldine Chaucer of 1845, realised that the solution of the problem was the construction of a pedigree; but the tree he drew up was quite inade quate for the purpose. The earliest record of the coats is in the notebook of Richard Lee, Port cullis, who sketched them for his Gatherings of Oxfordshire on his Visitation of the County in 1574. It is now in the Bodleian (Wood MS. D. 14), and a page of it, showing some of the shields on the Ewelme tombs, was reproduced in facsimile in the Harleian Society'S volume of the Visitations of Oxfordshire. -

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

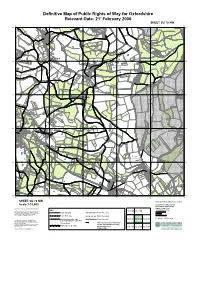

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 78 NW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 78 NW 70 71 72 73 74 75 B 480 1200 7900 B 480 8200 0005 Highclere B 480 7300 The Well The B 480 Croft Crown Inn The Old School House Unity Cottage 322/25 90 Pishilbury 90 377/30 Cottage Hall 322/21 Well 322/20 Pool Walnut Tree Cottage 3 THE OLD ROAD 2/2 32 Bank Farm Walnut Tree Cottage 8086 CHURCH HILL The Beehive Balhams' Farmhouse Pishill Church 9683 LANE 2/22 6284 Well Pond Hall Kiln BALHAM'S Barn 32 PISHILL Kiln Pond 322/22 6579 Cottages 0076 322/22 HOLLANDRIDGE LANE Upper Nuttalls Farm 322/16 Chapel Wells Pond 0076 Thatchers Pishill House 0974 322/15 5273 Green Patch 322/25 Rose Cottage Pond B 480 The Orchard B 480 7767 Horseshoe Cottage Strathmore The 322/17 37 Old Chapel Lincolns Thatch Cottage Ramblers Hey The White House 7/ Goddards Cottage 322/22 The Old Farm House 30 April Cottage The Cottage Softs Corner Tithe Barn Law Lane 377/30 Whitfield Flint Cottage Commonside Cedarcroft BALHAM'S LANE 322/20 322/ Brackenhurst Beech Barn 0054 0054 27 322/23 6751 Well 322/10 Whistling Cottage 0048 5046 Morigay Nuttall's Farm Tower Marymead Russell's Water 2839 Farm 377/14 Whitepond Farm 322/9 0003 377/15 7534 0034 Pond 0034 Redpitts Lane Little Balhams Pond Elm Tree Hollow Snowball Hill 1429 Ponds Stonor House Well and remains of 0024 3823 Pond 2420 Drain RC Chapel Pond (Private) 5718 Pond Pond Pond 322/20 Redpitts Farm 9017 0513 Pond Pavilion Lodge Lodge 0034 The Bungalow 1706 0305 9 4505 Periwinkle 7/1 Cottage 0006 Well 322/10 0003 -

Chaucer's Official Life

CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE JAMES ROOT HULBERT CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE Table of Contents CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE..............................................................................................................................1 JAMES ROOT HULBERT............................................................................................................................2 NOTE.............................................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................4 THE ESQUIRES OF THE KING'S HOUSEHOLD...................................................................................................7 THEIR FAMILIES........................................................................................................................................8 APPOINTMENT.........................................................................................................................................12 CLASSIFICATION.....................................................................................................................................13 SERVICES...................................................................................................................................................16 REWARDS..................................................................................................................................................18 -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Stapylton Final Version

1 THE PARLIAMENTARY PRIVILEGE OF FREEDOM FROM ARREST, 1603–1629 Keith A. T. Stapylton UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Page 2 DECLARATION I, Keith Anthony Thomas Stapylton, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed Page 3 ABSTRACT This thesis considers the English parliamentary privilege of freedom from arrest (and other legal processes), 1603-1629. Although it is under-represented in the historiography, the early Stuart Commons cherished this particular privilege as much as they valued freedom of speech. Previously one of the privileges requested from the monarch at the start of a parliament, by the seventeenth century freedom from arrest was increasingly claimed as an ‘ancient’, ‘undoubted’ right that secured the attendance of members, and safeguarded their honour, dignity, property, and ‘necessary’ servants. Uncertainty over the status and operation of the privilege was a major contemporary issue, and this prompted key questions for research. First, did ill definition of the constitutional relationship between the crown and its prerogatives, and parliament and its privileges, lead to tensions, increasingly polemical attitudes, and a questioning of the royal prerogative? Where did sovereignty now lie? Second, was it important to maximise the scope of the privilege, if parliament was to carry out its business properly? Did ad hoc management of individual privilege cases nevertheless have the cumulative effect of enhancing the authority and confidence of the Commons? Third, to what extent was the exploitation or abuse of privilege an unintended consequence of the strengthening of the Commons’ authority in matters of privilege? Such matters are not treated discretely, but are embedded within chapters that follow a thematic, broadly chronological approach. -

Sarah L. Peverley a Tretis Compiled out of Diverse Cronicles (1440): A

Sarah L. Peverley A Tretis Compiled out of Diverse Cronicles (1440): A Study and Edition of the Short English Prose Chronicle Extant in London, British Library, Additional 34,764 Sarah L. Peverley Introduction The short English prose chronicle extant in London, British Library, MS Additional 34,764 has never been edited or received any serious critical attention.1 Styled as ‘a tretis compiled oute of diuerse cronicles’ (hereafter Tretis), the text was completed in ‘the xviij yere’ of King Henry VI of England (1439–1440) by an anonymous author with an interest in, and likely connection with, Cheshire. Scholars’ neglect of the Tretis to date is largely attributable to the fact that it has been described as a ‘brief and unimportant’ account of English history, comprising a genealogy of the English kings derived from Aelred of Rievalux’s Genealogia regum Anglorum and a description of England abridged from Book One of Ranulph Higden’s Polychronicon.2 While the author does utilize these works, parts of the Tretis are nevertheless drawn from other sources and the combination of the materials is more sophisticated than has hitherto been acknowledged. Beyond the content of the Tretis, the manuscript containing it also needs reviewing. As well as being the only manuscript in which the Tretis has been identified to date, Additional 34,764 was once part of a (now disassembled) fifteenth- century miscellany produced in the Midlands circa 1475. The miscellany was 1 To date, the only scholar to pay attention to the nature of the text is Edward Donald Kennedy, who wrote two short entries on the chronicle (Kennedy 1989: 2665-2666, 2880-2881; 2010: 1). -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

The Lancastrian Retreate from Populist Discourse? Propaganda

The Lancastrian Retreat from Populist Discourse? Propaganda Conflicts in the Wars of the Roses Andrew Broertjes University of Western Australia This article explores an aspect of the propaganda wars that were conducted between the Lancastrian and Yorkist sides during the series of conflicts historians refer to as the Wars of the Roses. I argue that by the end of the 1450s, the Lancastrians had abandoned the pursuit of the popular voice (“the commons”, “the people”), instead treating this group with suspicion and disdain, expressed primarily through documents such as the Somnium Vigilantis and George Ashby’s Active Policy of a Prince. This article examines how the Lancastrians may have had populist leanings at the start of their rule, the reigns of Henry IV and Henry V, but moved away from such an approach, starting with the Jack Cade rebellion, and the various Yorkist uprisings of the 1450s. The composition of this group, “the people”, will also be examined, with the question being raised as to who they might have been, and why their support became a necessary part of the Wars of the Roses. In November 1459 what historians would later refer to as “the Parliament of Devils” met in Coventry.1 Convening after the confrontation between Yorkists and Lancastrians at Ludford Bridge, this parliament, consisting mainly of partisan Lancastrians, passed acts of attainder against the leading figures of the Yorkist faction.2 The Yorkists had already fled the country, retreating to Calais and Ireland, preparing for an extraordinary political comeback that would culminate in the coronation of Edward IV in March 1461. -

Edward of Lanchaster; Crosby Place; 2011 Chicago AGM; and 2011

Richard III Society, Inc. Vol. 42 No. 4 December, 2011 Challenge in the Mist by Graham Turner Dawn on the 14th April 1471, Richard Duke of Gloucester and his men strain to pick out the Lancastrian army through the thick mist that envelopes the battlefield at Barnet. Printed with permission l Copyright © 2000 Articles on: American Branch Annual Reports; Edward of Lanchaster; Crosby Place; 2011 Chicago AGM; and 2011 Ricardian Tour Report Inside cover (not printed) Contents Annual Reports: Richard III Society, American Branch......................2 Treasurer’s Report.........................................................................................................2 Chairman’s Report.........................................................................................................8 Vice Chairman’s Report................................................................................................8 Secretary’s Report..........................................................................................................8 Membership Chair Report:............................................................................................8 Annual Report from the Research Librarian..................................................................9 Sales Office Report .......................................................................................................9 Editor’s Report.............................................................................................................11 A Few Words from the Editor................................................................12 -

Edmund Plowden, Master Treasurer of the Middle Temple

The Catholic Lawyer Volume 3 Number 1 Volume 3, January 1957, Number 1 Article 7 Edmund Plowden, Master Treasurer of the Middle Temple Richard O'Sullivan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/tcl Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Catholic Lawyer by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDMUND PLOWDEN' MASTER TREASURER OF THE MIDDLE TEMPLE (1561-1570) RICHARD O'SULLIVAN D ENUO SURREXIT DOMUS: the Latin inscription high on the outside wall of this stately building announces and records the fact that in the year 1949, under the hand of our Royal Treasurer, Elizabeth the Queen, the Hall of the Middle Temple rose again and became once more the centre of our professional life and aspiration. To those who early in the war had seen the destruction of these walls and the shattering of the screen and the disappearance of the Minstrels' Gallery; and to those who saw the timbers of the roof ablaze upon a certain -midnight in March 1944, the restoration of Domus must seem something of a miracle. All these things naturally link our thought with the work and the memory of Edmund Plowden who, in the reign of an earlier Queen Elizabeth, devoted his years as Treasurer and as Master of the House to the building of this noble Hall. -

Berrick Salome NP Pre

BERRICK SALOME PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN Pre-Submission Plan 2013–2033 NOVEMBER 2018 – DRAFT v10 Published by Berrick Salome Parish Council under the Neighbourhood Planning (General) Regulations 2012 Contents LIST OF LAND USE POLICIES ............................................................................................................................ 3 FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................... 6 The Neighbourhood Planning Team ........................................................................................................... 7 Strategic Environmental Assessment & Habitats Regulations Assessment ............................................... 8 Consultation ............................................................................................................................................... 8 2. THE NEIGHBOURHOOD AREA ..................................................................................................................... 9 A Profile of the Parish ................................................................................................................................. 9 Early history .............................................................................................................................................. 10 St Helens Church