Housing Plan for LGBTQ+ Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYC TOHP Transcript 142 Lorena Borjas

NEW YORK CITY TRANS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT https://www.nyctransoralhistory.org/ http://oralhistory.nypl.org/neighborhoods/trans-history INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT LORENA BORJAS Interviewer: Lorenzo Van Ness Date of Interview: June 11, 2017 Location of Interview: El Rico Tino, Jackson Heights, Queens Interview Recording URL: http://oralhistory.nypl.org/interviews/lorena-borjas-ugsqdb Transcript URL: https://s3.amazonaws.com/oral- history/transcripts/NYC+TOHP+Transcript+142+Lorena+Borjas.pdf Transcribed by Cynthia Citlallin Delgado (volunteer) NYC TOHP Interview Transcript #142 RIGHTS STATEMENT The New York Public Library has dedicated this work to the public domain under the terms of a Creative Commons CC0 Dedication by waiving all of its rights to the work worldwide under copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights, to the extent allowed by law. Though not required, if you want to credit us as the source, please use the following statement, "From The New York Public Library and the New York City Trans Oral History Project." Doing so helps us track how the work is used and helps justify freely releasing even more content in the future. NYC TOHP Transcript #142: Lorena Borjas - Page 2 (of 15) Lorenzo Van Ness: Hola, mi nombre es Lorenzo Van Ness y yo voy a estar teniendo una conversación con Lorena Borjas para el proyecto de Nueva York de Historia Oral Trans, en colaboración con la librería publica de Nueva York. Este es un proyecto de historia oral centrado en la experiencia de las personas que se identifican como trans. Hoy es el 11 de junio de 2017, y lo estamos haciendo en El Rico Tinto, en Jackson Heights. -

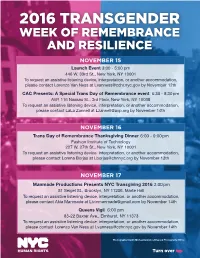

2016 Transgender Week of Remembrance and Resilience

2016 TRANSGENDER WEEK OF REMEMBRANCE AND RESILIENCE NOVEMBER 15 Launch Event 3:00 - 5:00 pm 446 W. 33rd St., New York, NY 10001 To request an assistive listening device, interpretation, or another accommodation, please contact Lorenzo Van Ness at [email protected] by November 12th CAC Presents: A Special Trans Day of Remembrance event 6:30 - 8:30 pm AVP, 116 Nassau St., 3rd Floor, New York, NY 10038 To request an assistive listening device, interpretation, or another accommodation, please contact LaLa Zannell at [email protected] by November 14th NOVEMBER 16 Trans Day of Remembrance Thanksgiving Dinner 6:00 - 9:00 pm Fashion Institute of Technology 227 W. 27th St., New York, NY 10001 To request an assistive listening device, interpretation, or another accommodation, please contact Lorena Borjas at [email protected] by November 13th NOVEMBER 17 Manmade Productions Presents NYC Transgiving 2016 3:00 pm 81 Seigel St., Brooklyn, NY 11206, Marte Hall To request an assistive listening device, interpretation, or another accommodation, please contact Akia Manmade at [email protected] by November 14th Queens Vigil 6:00 pm 83-22 Baxter Ave., Elmhurst, NY 11373 To request an assistive listening device, interpretation, or another accommodation, please contact Lorenzo Van Ness at [email protected] by November 14th Photography Credit: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office Turn over ➥ NOVEMBER 18 Trans Day of Remembrance 7:00 pm 208 W. 13th St., New York, NY 10011 To request an assistive listening device, interpretation, or another accommodation, please contact Ali Belen at [email protected] by November 15th NOVEMBER 19 Trans Day of Remembrance at the Pride Center of Staten Island 11:00 am - 6:30 pm 25 Victory Blvd., 3rd Floor, Staten Island, NY 10305 To request an assistive listening device, interpretation, or another accommodation, please contact Marcy Carr at [email protected] by November 15th Mr & Miss NY Black Trans Pageant 5:00 pm Copacabana, 268 W. -

LGBTIQ+ and SEX WORKER RIGHTS DEFENDERS at RISK DURING COVID-19 DECEMBER 2020 Acknowledgements

LGBTIQ+ AND SEX WORKER RIGHTS DEFENDERS AT RISK DURING COVID-19 DECEMBER 2020 Acknowledgements This report was researched and written by Erin Kilbride, AJWS (Kenya); Alma Magaña, Assistant to the Executive Research and Visibility Coordinator at Front Line Director, Fondo Semillas (Mexico); Dr. Stellah Wairimu Defenders. The report was reviewed by: Meerim Ilyas, Bosire and Mukami Marete, Co-Directors, UHAI-EASHRI Deputy Head of Protection and Gender Lead; Fidelis (Kenya); Vera Rodriguez and Nadia van der Linde, Red Mudimu, Africa Protection Coordinator; Adam Shapiro, Umbrella Fund (Netherlands); Adrian Jjuuko, Executive Head of Communications and Visibility; Ed O’Donovan, Director, Human Rights Awareness and Promotion Head of Protection; Caitriona Rice, Head of Protection Forum (Uganda); and Wenty, Coordinator, Eagle Wings Grants; Olive Moore, Deputy Director, and Andrew (Tanzania). Anderson, Executive Director. Front Line Defenders also wishes to thank Sienna Baskin, Front Line Defenders is grateful for the external reviews Director of Anti-Trafficking Fund at NEO Philanthropy, provided by: Javid Syed, Director of Sexual Health and and Julia Lukomnik, Senior Program Officer in Public Rights, AJWS (US); Gitahi Githuku, Program Officer, Health at Open Society Foundations, for their input. Credits Cover Illustrations: Sravya Attaluri From top, the illustrations depict human rights defenders Jaime Montejo of Mexico (page 31), Clara Devis of Tanzania (page 19), Thenu Ranketh of Sri Lanka (page 27) and Yazmin Musenguzi of Tanzania. Report Design and layout: Colin Brennan Table of Contents I. WHRD Blog: Trauma & Resilience During COVID-19 4-5 II. Introduction 6-10 1. Executive Summary 2. Methodology 3. Terminology 4. Sex Worker Rights Defenders 5. -

The 2020 TJFP Team

On the Precipice of Trans Justice Funding Project 2020 Annual Report Contents 2 Acknowledgements 4 Terminology 5 Letter from the Executive Director 11 Our Grantmaking Year in Review 20 Grantees by Region and Issue Areas 22 The 2020 TJFP Team 27 Creating a Vision for Funding Trans Justice 29 Welcoming Growth 34 Funding Criteria 35 Some of the Things We Think About When We Make Grants 37 From Grantee to Fellow to Facilitator 40 Reflections From the Table 43 Our Funding Model as a Non-Charitable Trust 45 Map of 2020 Grantees 49 Our 2020 Grantees 71 Donor Reflections 72 Thank You to Our Donors! This report and more resources are available at transjusticefundingproject.org. Acknowledgements We recognize that none of this would have been possible without the support of generous individuals and fierce communities from across the nation. Thank you to everyone who submitted an application, selected grantees, volunteered, spoke on behalf of the project, shared your wisdom and feedback with us, asked how you could help, made a donation, and cheered us on. Most of all, we thank you for trusting and supporting trans leadership. A special shoutout to our TJFP team, our Community Grantmaking Fellows and facilitators; Karen Pittelman; Nico Amador; Cristina Herrera; Zakia Mckensey; V Varun Chaudhry; Stephen Switzer at Rye Financials; Raquel Willis; Team Dresh, Jasper Lotti; butch.queen; Shakina; Nat Stratton-Clarke and the staff at Cafe Flora; Rebecca Fox; Alex Lee of the Grantmakers United for Trans Communities program at Funders for LGBT Issues; Kris -

Lorena Borjas

“Let no one take away We mourn the passing of Latinx immigrants. For decades, beloved trans-Latina and Lorena worked as an educator our desire to fight. in HIV testing, syringe exchange, immigrant rights activist and other programs with LGBTQ Let’s fight until the Lorena Borjas, honored by state last moment and local leaders and known in organizations, including Translatina Queens and throughout NYC as Network, Latino Commission on of our life.” the mother of her community. AIDS, and Community Healthcare On March 30, Lorena died of Network. In 2011, she launched complications from COVID-19. the Lorena Borjas Legal Fund to provide bail and advocate for In 1981 at age 20, Lorena moved LGBTQ and other immigrants. from her native Mexico City to Most recently, Lorena served as Queens, where she shared an Executive Director of Colectivo apartment with 20 fellow trans- Intercultural TRANSgrediendo. Our Community Leaders Pay Homage to Lorena “ Lorena Borjas was a tireless transgender activist who took advantage of her own experiences as a transgender woman, immigrant, and sex worker to help others. She had a great dream, to build a home where transgender women found refuge and support. Casa Trans Lorena Borjas was her life project. Unfortunately, she could not see her dream materialize. We will continue her legacy to make Casa Trans Lorena Borjas a reality, and provide all the necessary support that the community needs.” Liaam Winslet, Acting Executive Director Colectivo Intercultural TRANSgrediendo Remembering “ Lorena worked as a tireless, longtime advocate for immigrants, sex workers, and people of transgender experience. She was a great friend to Amida Care and a beautiful and bright light in our world. -

¿Quien Llora a Las Mujeres Invisibles? / Who Mourns the Invisible Women?

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Capstones Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Fall 12-14-2018 ¿Quien llora a las mujeres invisibles? / Who Mourns The Invisible Women? Sindy A. Nanclares Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Sofía Cerda Campero Craig Newmark Graduate School How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gj_etds/301 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ¿Quién llora a las mujeres invisibles? Las mujeres transgénero tienen una esperanza de vida de 35 años. La violencia, el maltrato y la falta de oportunidad contribuyen a su muerte temprana. La dignidad para esta comunidad no llega ni siquiera con la muerte. Por: Sofía Cerda Campero y Sindy Nanclares El viernes 12 de octubre, el conductor de televisión Raúl de Molina se presentó en Times Square, corazón de Nueva York, para una transmisión en vivo del programa “El gordo y la flaca”, un show de Univision que desde hace más de 20 años reseña lo más importante de la farándula y el entretenimiento: desde los amores de JLo hasta las cirugías de Laura Bozzo. Era una tarde fresca y De Molina, conocido como El Gordo, llevaba un traje azul rey con una bufanda de seda; zapatos bien lustrados; el pelo relamido hacia atrás. No tenía manera de saber que un grupo de doce mujeres, confundidas entre el público curioso de la calle, se preparaba para confrontarlo en televisión nacional. -

Press Release

Paradise and Other Fires solo exhibition by Leslie Brack May 8 - June 20, 2021 opening reception May 8, 12-7PM The descent to hell is easy / Its doors are open wide / But to regain the air of Paradise / And view again its hopeful skies / This is the struggle and the labor / It’s here the trouble lies. --Virgil’s Aeneid In Paradise and Other Fires, Leslie Brack’s nine narcotic and explosive watercolors of recent wildfires and urban upheavals offer a dark but blazing descent into the present. At the entry, an unseen incineration. A delicate, defoliated landscape drained of color and of life. An ominous space for contemplation. Brack’s show opens with a blast from the past, an image of a WWI no man’s land that slows and then propels us into warmer scenes of smog and palms--our tropical apocalypse. And then, the gallery explodes, crackling with Brack’s fierce and ravishing fires. Six blazing hot paintings, in glowing reds and oranges, ignite the gallery. Riots and wildfires burn from Portland to Malibu, from Atlanta to Rio. Torched trucks roar, tail-lights burn through crimson clouds, buildings smolder in a wall of heat or erupt into blinding light. Their aqueous medium makes the flames weirdly watery; their spilling, liquid colors prompting us to hear the word “bleed” as we look. Brack’s saturated pigmentation amplifies the violence of the scenes, while their material delicacy signals fragility. Each painting’s wild chaos belies their fanatical control, and the tension between the gorgeous, detailed, jewel-like work and the ferocity of the subjects is, of course, part of their seduction. -

Waste Equity Bill Officially Dead

LOCAL CLASSIFIEDS PAGE 11 Jan. 7, 2018 Your Neighborhood — Your News® Guv unveils Waste equity bill offi cially dead plan to end Miller withdraws support from environmental legislation he co-sponsored in 2014 food shaming BY NAEISHA ROSE not to support Intro 495-C, there- Brooklyn and the South Bronx. cent of New York City’s trash with fore killing the waste equity bill he The purpose of the bill, which caps on the number of refuse sent BY NAEISHA ROSE Community leaders in Queens co-sponsored in 2014. The bill could was rooted in the 2006 Solid Waste to them, according to the Depart- and environmentalists were shocked have helped to reduce the garbage Management Plan, was to help ment of Sanitation. The bill would Ahead of his State of the last month when Councilman I. stations in low-income neighbor- southeast Queens and other com- have cut traffic and pollution and State address Wednesday, Gov. Daneek Miller (D-St. Albans) chose hoods in southeast Queens, north munities overburdened with 75 per- improved air quality while com- Andrew Cuomo previewed his mercial Marine Transfer Stations five-step plan to combat hunger were created. for food insecure students from The city’s SWMP would have kindergarten through college. switched garbage transfer from Cuomo’s announcement could THREE KINGS DAY IN CORONA long-haul trucking to marine and not have come at a better time rail transfer, according to www. for Queens’ children. waste360.com. Throughout Queens, there Waste360.com, a site that follows are 63,798 children who were in trends in solid waste, stated truck food insecure homes from 2014 travel would have went down by 60 to 2016, according to statistics miles and greenhouse gas emissions reported by the non-profit Hun- would be reduced 34,000 tons. -

Pols Pass Queens Library Reform

• JAMAICA TIMES • ASTORIA TIMES • FOREST HILLS LEDGER • LAURELTON TIMES LARGEST AUDITED • QUEENS VILLAGE TIMES COMMUNITY • RIDGEWOOD LEDGER NEWSPAPER IN QUEENS • HOWARD BEACH TIMES • RICHMOND HILL TIMES June 27–July 3, 2014 Your Neighborhood - Your News® FREE ALSO COVERING ELMHURST, JACKSON HEIGHTS, LONG ISLAND CITY, MASPETH, MIDDLE VILLAGE, REGO PARK, SUNNYSIDE July 4th fi reworks may Visit us online LIC artist be visible in boro TimesLedger.com emotes Page 4 QGuide Page 39 TimesLedger Pols pass Queens Library reform sold to former Board members president, wife HONORING A SOUTHEAST QUEENS LEADER can be replaced BY NATHAN TEMPEY under new rules News executives Les Good- stein and his wife Jennifer are BY ALEX ROBINSON buying the Community Newspa- per Group — the umbrella com- State lawmakers set politi- pany that publishes TimesLedger cal differences aside last week to Newspapers, the Brooklyn Paper, make sure the state Legislature Brooklyn Courier-Life, the Bronx passed a Queens Library reform Times, Caribbean Life and sev- bill. eral other weekly papers and spe- Once Gov. Andrew Cuomo cialty magazines — from News signs the bill, it will reform the Corp. library’s board of trustees, giving The husband-and-wife team the mayor and borough president made the announcement to the power to remove board members. assembled staff at the Brooklyn The bill was authored by headquarters of CNG Monday state Assemblyman Jeffrion Au- morning. bry (D-East Elmhurst) and Bor- Les Goodstein formed the ough President Melinda Katz af- Community Newspaper Group as ter the board of trustees failed to an executive for the international oust or suspend the library’s chief media conglomerate News Corp., executive officer, Thomas Galan- overseeing it as president until te, following allegations of fiscal his retirement in July 2013. -

1 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 1:13 P.M. Acting Speaker

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2021 1:13 P.M. ACTING SPEAKER AUBRY: The House will come to order. In the absence of clergy, let us pause for a moment of silence. (Whereupon, a moment of silence was observed.) Visitors are invited to join the members in the Pledge of Allegiance. (Whereupon, Acting Speaker Aubry led members and visitors in the Pledge of Allegiance.) A quorum being present, the Clerk will read the Journal of Monday, February 1st. Mrs. Peoples-Stokes. MRS. PEOPLES-STOKES: Mr. Speaker, I move to 1 NYS ASSEMBLY FEBRUARY 2, 2021 dispense with the further reading of the Journal of Monday, February the 1st and ask that the same stand approved. ACTING SPEAKER AUBRY: Without objection, so ordered. Mrs. Peoples-Stokes. MRS. PEOPLES-STOKES: Thank you, Mr. Speaker. I'd just like to take an opportunity to share a quote for today. This quote is from the song Lift Every Voice and Sing, which is often called the National Black Anthem. It was written as a poem by NAACP leader James Welden Johnson in 1871. It was set to music by his brother, Raymond Johnson, in 1873 and in 1899, it was first performed in the public by the Johnson's hometown of Jacksonville, Florida as a part of a celebration of Lincoln's Birthday on February the 12th, 1990 -- 1900 by a choir of 500 schoolchildren and the segregated Stanton School where James Welden Johnson was the principal. Mr. Speaker, the words: "Stony the road we trod, bitter the chastening rod felt in the days when hope unborn had died. -

LGBTQ Community

We All Matter Health Advocacy Care This turbulent time we are all living through health navigators like Faith Kamara and Victwan McCorkle, challenges New Yorkers to rise to the occasion serving and supporting our members out in the community; and reinvent ourselves in ways large and the pioneering contributions of NYC-based organizations small. Amida Care has also been undergoing like The Anti-Violence Project and Out My Closet; and the a process of renewal and transformation, as unforgettable legacy of Lorena Borjas, a renowned trans-Latina reflected in our latest community magazine: activist whom we recently lost to Covid-19. Lorena is fondly Health, Advocacy, Care. remembered here in tributes from several community members whose lives she touched. Its title debuts our organization’s new tagline – one that we believe better sums up our mission and more clearly Health, advocacy, and care are also found in the work of those communicates who we are. What most sets Amida Care apart is who promote healthy self-care, self-expression, and body advocacy to help members and communities gain access to the positivity, like artist/advocate Tarik Carroll of the EveryMAN care they need, so they can protect and improve their health Project and others profiled or quoted in these pages. Each does and live their best, most authentic lives. their part to build a safer, more inclusive LGBTQ community. The coronavirus pandemic is shining a light on the glaring Now more than ever, Amida Care and our community partners health inequities among New Yorkers of color. Amida Care has are answering the call to lean in and advocate for the health and been a longstanding advocate to end the health disparities that care of our members and communities. -

Women of HONORING WOMEN in NEW YORK May 7, 2019 Dear Friends, Thank You for Attending This Year’S Women of Distinction Celebration

Senator Andrea Stewart-Cousins Senator John J. Flanagan DISTINCTIONWomen of HONORING WOMEN IN NEW YORK May 7, 2019 Dear Friends, Thank you for attending this year’s Women of Distinction celebration. Each year, the New York State Senate honors a select group of exemplary women who make our world and our lives better. These New York State citizens are remarkable in their contributions – enriching the quality of life in their communities and beyond. Today, we pay homage to the 2019 honorees who depict the ideals of competence, leadership and service in their chosen fields. Over the past twenty years, our nominees have achieved extraordinary success in all fields, including civil rights, science, athletics, education, the arts and many other purpose-driven activities. These women are leaders and visionaries who open doors, break glass ceilings, and are an inspiration to us all. This year’s honorees continue in this tradition – they have overcome challenges and provided their communities with outstanding service and superior talents. On behalf of the New York State Senate, we would like to offer our wholehearted congratulations to the 2019 Women of Distinction. We are humbled to be in the presence of these talented women, and we are inspired by their work showcased here today. It is with great pride and pleasure that we honor your dedication, commitment and success. Sincerely, Senator Andrea Stewart-Cousins Senator John J. Flanagan Temporary President Minority Leader and Majority Leader DISTINCTIONWomen of HONORING WOMEN IN NEW YORK LEGISLATIVE