Forested Tidal Wetland Communities of Maryland's Eastern Shore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 6 – Biological Resources 6 - 1 Draft EIR Mill Creek Project June 2018 and Features Adjacent Woodlands

Draft EIR Mill Creek Project June 2018 6 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 6.1 INTRODUCTION The Biological Resources chapter of the EIR evaluates the biological resources known to occur or potentially occur within the Mill Creek Project (proposed project) site, as well as biological resources known to occur in off-site areas where off-site project work may occur. This chapter describes potential impacts to those resources, and identifies measures to reduce those impacts to less-than-significant levels. Existing plant communities, wetlands, wildlife habitats, and potential for special-status species and communities are discussed for the project area. The information contained in this analysis is primarily based on the Biological Resources Assessment1 and the Special-Status Plant Survey Report2 prepared by Madrone Ecological Consulting, LLC (Madrone). Information concerning existing on-site trees was provided by the Arborist Reports prepared by Abacus Consulting Arborists. Further information was sourced from the Placer County General Plan,3 the Placer County General Plan EIR,4 and the Dry Creek-West Placer Community Plan (DCWPCP).5 6.2 EXISTING ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING The following sections describe the existing environmental setting related to biological resources occurring in the proposed project area. Regional Setting The proposed project site is located north of Antelope and southwest of the City of Roseville, in an unincorporated portion of western Placer County, within the DCWPCP. The DCWPCP experiences a Mediterranean type climate with cool, wet winters, and hot, dry summers. Temperatures in the project area fluctuate from average highs in July of 95 degrees Fahrenheit, with average lows in December and January, averaging 39 degrees Fahrenheit for both months. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Biosphere Consulting 14908 Tilden Road ‐ Winter Garden FL 34787 (407) 656 8277

Biosphere Consulting 14908 Tilden Road ‐ Winter Garden FL 34787 (407) 656 8277 www.BiosphereNursery.com The following list of plants include only native wetland and transitional species used primarily in aquascaping, lakefront and wetland restoration. Biosphere also carries a large number of upland species and BIOSCAPE species, as well as wildflower seeds and plants. The nursery is open to the public on Tuesday through Saturday only from 9:00 A.M. until 5:00 P.M. Prices are F.O.B. the nursery. * Bare root plants must be ordered at least two (2) days prior to pick-up. PRICE LIST NATIVE WETLAND AND TRANSITIONAL SPECIES HERBACEOUS SPECIES *Bare Root 1 Gal. 3 Gal. Arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia) .50 2.50 --- Bulrush (Scirpus californicus & S.validus) .50 --- 8.00 Burrmarigold (Bidens leavis) --- 2.00 --- Canna (Canna flaccida) .60 2.00 --- Crinum (Crinum americanum) 1.50 3.00 10.00 Duck Potato (Sagittaria lancifolia) .60 2.00 --- Fragrant Water Lily (Nymphaea odorata) 5.00 --- 12.00 Hibiscus (Hibiscus coccinea) --- 3.00 8.00 Horsetail (Equisetum sp.) .80 2.00 --- Iris (Iris savannarum) .60 2.00 --- Knotgrass (Paspalum distichum) .50 2.00 --- Lemon Bacopa (Bacopa caroliniana) --- 3.50 --- Lizards Tail (Saururus cernuus) .60 2.50 --- Maidencane (Panicum hemitomon) .50 2.00 --- Pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata) .50 2.00 --- Redroot (Lachnanthes carolinana) .60 2.00 --- Sand Cord Grass (Spartina bakeri) .50 3.50 --- Sawgrass (Cladium jamaicense) .60 3.00 --- Softrush (Juncus effusus) .50 2.00 --- Spikerush (Eleocharis cellulosa) .70 2.00 --- -

Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Honors Theses Honors College Spring 5-2016 Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi Hanna M. Miller University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Hanna M., "Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi" (2016). Honors Theses. 389. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/389 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi by Hanna Miller A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in the Department of Biological Sciences May 2016 ii Approved by _________________________________ Mac H. Alford, Ph.D., Thesis Adviser Professor of Biological Sciences _________________________________ Shiao Y. Wang, Ph.D., Chair Department of Biological Sciences _________________________________ Ellen Weinauer, Ph.D., Dean Honors College iii Abstract The North American Coastal Plain contains some of the highest plant diversity in the temperate world. However, most of the region has remained unstudied, resulting in a lack of knowledge about the unique plant communities present there. -

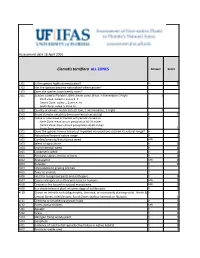

WRA.Datasheet.Template (Version 1) (Version 1).Xlsx

Assessment date 18 April 2016 Clematis terniflora ALL ZONES Answer Score 1.01 Is the species highly domesticated? n 0 1.02 Has the species become naturalised where grown? 1.03 Does the species have weedy races? 2.01 Species suited to Florida's USDA climate zones (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) 2 North Zone: suited to Zones 8, 9 Central Zone: suited to Zones 9, 10 South Zone: suited to Zone 10 2.02 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) 2 2.03 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y 1 2.04 Native or naturalized in habitats with periodic inundation y North Zone: mean annual precipitation 50-70 inches Central Zone: mean annual precipitation 40-60 inches South Zone: mean annual precipitation 40-60 inches 1 2.05 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y 3.01 Naturalized beyond native range y 2 3.02 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed unk 3.03 Weed of agriculture n 0 3.04 Environmental weed y 4 3.05 Congeneric weed y 2 4.01 Produces spines, thorns or burrs n 0 4.02 Allelopathic unk 0 4.03 Parasitic n 0 4.04 Unpalatable to grazing animals ? 4.05 Toxic to animals ? 4.06 Host for recognised pests and pathogens n 0 4.07 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans unk 0 4.08 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems unk 0 4.09 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle n 0 4.10 Grows on infertile soils (oligotrophic, limerock, or excessively draining soils). -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Introduction to Common Native & Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska

Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska Cover photographs by (top to bottom, left to right): Tara Chestnut/Hannah E. Anderson, Jamie Fenneman, Vanessa Morgan, Dana Visalli, Jamie Fenneman, Lynda K. Moore and Denny Lassuy. Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska This document is based on An Aquatic Plant Identification Manual for Washington’s Freshwater Plants, which was modified with permission from the Washington State Department of Ecology, by the Center for Lakes and Reservoirs at Portland State University for Alaska Department of Fish and Game US Fish & Wildlife Service - Coastal Program US Fish & Wildlife Service - Aquatic Invasive Species Program December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................ x Introduction Overview ............................................................................. xvi How to Use This Manual .................................................... xvi Categories of Special Interest Imperiled, Rare and Uncommon Aquatic Species ..................... xx Indigenous Peoples Use of Aquatic Plants .............................. xxi Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts ................................................................................. xxi Vectors ................................................................................. xxii Prevention Tips .................................................... xxii Early Detection and Reporting -

Choptank Tributary Summary: a Summary of Trends in Tidal Water Quality and Associated Factors, 1985-2018

Choptank Tributary Summary: A summary of trends in tidal water quality and associated factors, 1985-2018. June 7, 2021 Prepared for the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) Partnership by the CBP Integrated Trends Analysis Team (ITAT) This tributary summary is a living document in draft form and has not gone through a formal peer review process. We are grateful for contributions to the development of these materials from the following individuals: Jeni Keisman, Rebecca Murphy, Olivia Devereux, Jimmy Webber, Qian Zhang, Meghan Petenbrink, Tom Butler, Zhaoying Wei, Jon Harcum, Renee Karrh, Mike Lane, and Elgin Perry. 1 Contents 1. Purpose and Scope .................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Location ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Watershed Physiography .................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Land Use .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Land Use ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.3 Tidal Waters and Stations ................................................................................................................... 8 3. Tidal -

Plant Succession on Burned Areas in Okefenokee Swamp Following the Fires of 1954 and 1955 EUGENE CYPERT Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge U.S

Plant Succession on Burned Areas in Okefenokee Swamp Following the Fires of 1954 and 1955 EUGENE CYPERT Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and 'Wildlife Waycross, GA 31501 INTRODUCTION IN 1954 and 1955, during an extreme drought, five major fires occurred in Okefenokee Swamp. These fires swept over approximately 318,000 acres of the swamp and 140,000 acres of the adjacent upland. In some areas in the swamp, the burning was severe enough to kill most of the timber and the understory vegetation and burn out pockets in the peat bed. Burns of this severity were usually small and spotty. Over most of the swamp, the burns were surface fires which generally killed most of the underbrush but rarely burned deep enough into the peat bed to kill the larger trees. In many places the swamp fires swept over lightly, burning surface duff and killing only the smaller underbrush. Some areas were missed entirely. On the upland adjacent to the swamp, the fires were very de structive, killing most of the pine timber on the 140,000 acres burned over. The destruction of pine forests on the upland and the severe 199 EUGENE CYPERT burns in the swamp caused considerable concern among conservation ists and neighboring land owners. It was believed desirable to learn something of the succession of vegetation on some of the more severely burned areas. Such knowl edge would add to an understanding of the ecology and history of the swamp and to an understanding of the relation that fires may have to swamp wildlife. -

Hydrocotyle Sibthorpioides and H. Batrachium (Araliaceae) New for New York State

Atha, D. 2017. Hydrocotyle sibthorpioides and H. batrachium (Araliaceae) new for New York State. Phytoneuron 2017-56: 1– 6. Published 21 August 2017. ISSN 2153 733X HYDROCOTYLE SIBTHORPIOIDES AND H. BATRACHIUM (ARALIACEAE) NEW FOR NEW YORK STATE DANIEL ATHA Center for Conservation Strategy New York Botanical Garden Bronx, New York 10458 [email protected] ABSTRACT Spontaneous populations of Hydrocotyle sibthorpioides (lawn marsh pennywort) and H. batrachium (Araliaceae) are documented for New York state for the first time. Hydrocotyle batrachium is also new to North America. Hydrocotyle sibthorpioides was first found in 2013 in Queens county; H. batrachium was first found in 2016 in Westchester county. Both species are native to eastern Asia and show potential to be aggressive invaders in southeastern New York, particularly in wetlands. A key to the species of Hydrocotyle in New York State is provided. Prior to this report four species of Hydrocotyle were known from New York state, all of them native and all but one state-listed rarities: H. umbellata – Rare; H. verticillata var. verticillata – Endangered; and H. ranunculoides – Endangered (Young 2010). Among the native New York species, only H. americana occurs in abundance in the state. It is the only species historically reported for New York City and has not been documented for New York City since 1901. The present report documents two additional species for the New York flora, both native to Asia and naturalized in southeastern New York. Fertile herbarium specimens and DNA samples were obtained for all cited specimens and are available for analysis. Hydrocotyle sibthorpioides Lam. Spontaneous populations of Hydrocotyle sibthorpioides in New York were first detected and identified in Queens County by Nick Wagerik in the summer of 2013. -

Presence of the Indole Alkaloid Reserpine in Bignonia Capreolata L

Available online on www.ijppr.com International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemical Research 2012; 4(3); 89-91 ISSN: 0975-4873 Research Article Presence of the Indole Alkaloid Reserpine in Bignonia Capreolata L. Clark. T1, *Lund. K.C.1,2 1Department of Botanical Medicine, Bastyr University, Kenmore WA, USA 2Bastyr University Research Institute, Kenmore WA, USA ABSTRACT Bignonia capreolatais a perennial semi-evergreen vine from the Southeast United States that was used as a medicine by the Native Americans but has since fallen out of use. A preliminary screen of B. capreolata suggested the presence of the indole alkaloid reserpine. This analysis was undertaken to 1) verify the presence reserpine using LC-MS referenced with an analytical standard of reserpine; and 2) if verified, quantitate the level of reserpine in B. capreolata leaf. LC-MS analysis has confirmed the presence of reserpine in B. capreolata, which makes this the only known plant outside the Apocynaceae family to contain this indole alkaloid. INTRODUCTION MATERIALS AND METHODS Bignonia capreolata(crossvine)is a perennial semi- Plant Material: Leaf and stem of Bignonia capreolataL. evergreen vine native to the Eastern United States. It is a were collected in near Shelby, Alabama (USA). A member of the Bignoniaceae family, a plant family sample of the plant material used for testing was predominately found in tropical and subtropical regions. authenticated by a botanist (George Yatskievych, PhD) It is known by the common name crossvine and has and submitted to the Missouri Botanical Gardens become a popular ornamental plant due to its showy herbarium (voucher #6257878). clusters of orange to red trumpet flowers1.Ethnobotanical Sample Preparation: Plant material was dried whole and use in North Americahas been documented for the leaves removed for processing.