The Psalms Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

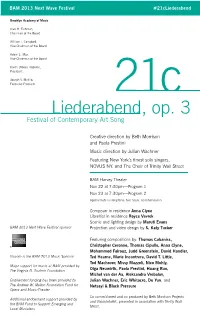

21C Liederabend, Op

Third biennial “Lieder-palooza” comes to BAM with 21c Liederabend, op. 3 on Nov 22 & 23 Contemporary art song recital spans two nights with nine world premieres and more than 30 new music and vocal luminaries 21c Liederabend, op. 3 / Festival of Contemporary Art Song Creative direction by Beth Morrison and Paola Prestini Music direction by Julian Wachner Featuring NOVUS NY, New York's finest solo singers, and The Choir of Trinity Wall Street Scenic and lighting design by Maruti Evans Projection design by S. Katy Tucker Featuring compositions by: Thomas Cabaniss, Christopher Ceronne, Thomas Cipullo, Anna Clyne, Mohammed Fairouz, Judd Greenstein, David Handler, Ted Hearne, Marie Incontrera, David T. Little, Tod Machover, Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Olga Neuwirth, Paola Prestini, Huang Ruo, Michel van der Aa, Aleksandra Vrebalov, Julian Wachner, Eric Whitacre, and Du Yun American Express is the BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor BAM Harvey Theater (651 Fulton St) Nov 22—Program 1 Nov 23—Program 2 7:30pm Tickets start at $20 Master Class: Art Song Forward with Christopher Burchett and Julian Wachner Nov 23 at 10:30am BAM Penthouse Studio (30 Lafayette Ave) $25 for singers; $15 for composers “…an expansive, at times explosive survey of contemporary art song, musical theater and opera.”—Time Out New York Brooklyn, NY/October 21, 2013—BAM presents 21c Liederabend, op.3, a 21st- century art song festival produced and curated by independent producers Beth Morrison of Beth Morrison Projects and Paola Prestini of VisionIntoArt. Called a 21st-century “Lieder-palooza” by WQXR, 21c Liederabend is an ambitious biennial that seeks to present the diverse and expansive styles of today’s art song. -

Marin Alsop Leads BSO, the Washington Chorus in 2010-2011

PRESS CONTACTS: Laura Farmer, 410.783.8024 [email protected] Claire Berlin, 410.783.8044 [email protected] Marin Alsop Leads BSO, The Washington Chorus in 2010‐2011 Season Finale, Verdi’s Requiem, June 9‐12 Baltimore, Md. (May 31, 2011) – The 2010‐2011 season will conclude with a performance of Verdi’s Requiem, featuring soprano Angela Meade, mezzo‐soprano Eve Gigliotti, tenor Roger Honeywell, and bass‐baritone Alfred Walker, supported by The Washington Chorus and led by Music Director Marin Alsop on Thursday, June 9 at 8 p.m., Friday, June 10 at 8 p.m. and Sunday, June 12 at 3 p.m. at the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall and Saturday, June 11 at 8 p.m. at the Music Center at Strathmore. Please see below for complete program details. Verdi composed Messa di Requiem in 1873. It is an epic musical setting of the Roman Catholic funeral mass, written as a memorial for the great Italian poet and novelist Alessandro Manzoni Verdi admired Manzoni, who’s works helped forge an Italian national identity. The work was premiered in 1874 at the San Marco Church in Milan during the first anniversary of Manzoni’s death. Joining the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra to perform this epic work is The Washington Chorus, under the direction of Julian Wachner. Back by popular demand, the Chorus collaborated with the BSO for last season’s finale concert of Brahms’ German Requiem. Also led by Maestra Alsop, The Baltimore Sun praised, “[Alsop] summoned considerable beauty of expression‐‐and plenty of power for the score’s few heated moments – from the BSO and the Washington Chorus.” Marin Alsop, conductor Hailed as one of the world’s leading conductors for her artistic vision and commitment to accessibility in classical music, Marin Alsop made history with her appointment as the 12th music director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. -

International Trumpet Guild Journal

Reprints from the International Trumpet Guild® Journal to promote communications among trumpet players around the world and to improve the artistic level of performance, teaching, and literature associated with the trumpet BLUE GREEN RED MVMT. II: GREEN FOR TRUMPET IN C AND ORGAN BY JULIAN WACHNER Copyright ©2015 International Trumpet Guild. All rights reserved. Used with permission. This file, originally published as a supplement to the June 2015 ITG Journal, contains the trumpet and organ parts for the second movement of this three-movement piece, the entirety of which is available from ECS Publishing. To access their website, CLICK HERE. The International Trumpet Guild is the copyright owner of all data contained in this file, and has given the International Trumpet Guild® (ITG) permission to offer this composition in this form with the following provisos: The individual end-user is hereby given the right to: • Download and retain an electronic copy of this file on a single workstation that is owned by the end-user • Print copies of this file for personal or educational use only The International Trumpet Guild®, in agreement with Julian Wachner, prohibits the following without prior writ ten permission: • Duplication or distribution of this file, the data contained herein, or printed copies made from this file for profit or for a charge, whether direct or indirect • Transmission, printing, or distribution of this file or the data contained herein in any form for any other reason than personal or educational use • Alteration of this file or the data contained herein • Placement of this file on any web site, server, or any other database or device that allows for the accessing or copying of this file or the data contained herein by any third party, including such a device intended to be used wholly within an institution. -

The Trinity Choir Trinity Baroque Orchestra

at One The Trinity Choir Trinity Baroque Orchestra Julian Wachner, Conductor Bach Cantatas · Schütz Motets Poetry Mondays at 1pm March 21–June 20, 2011 TRINITY WALL STREET presents The Trinity Choir & Trinity Baroque Orchestra Julian Wachner, Conductor at One weekly service featuring the cantatas of J.S. Bach, with motets of Heinrich Schütz, and transformative readings by contemporary poets Mondays at 1pm March 21–June 20, 2011* St. Paul’s Chapel Broadway at Fulton * This program booklet May 2 - June 20 WELCOME WELCOME to BACH at ONE, A miD-DAY serVICE of cantatas, PRAYERS, anD poetry. Bach, a devout Lutheran, composed 200 cantatas using both sacred and secular texts. Many of those cantatas are heard in churches around the world every Sunday, but through Bach at One, your Monday lunch hour can be enriched by timeless cantatas. Motets by Heinrich Schütz, an influential predecessor of Bach will also be presented, as will poetry readings by a group of noted poets. If you enjoy this peaceful and sacred interlude to your day, please know you are warmly invited back—to Bach at One, or to another of the worship opportunities at St. Paul’s or at Trinity Church. In particular, I call your attention to Sunday morning services at 8am and 10am here, and a new service of Compline, or prayers for the end of the day. Compline is an ancient half-hour candlelit service of chant and new music sung by the Trinity Choir. Imagine your day ending with you and others saying together: It is night after a long day. -

Virtual BACH FESTIVAL OREGON BACH FESTIVAL 2021

LISTENING GUIDE June 25- July 11, 2021 OREGONVirtual BACH FESTIVAL OREGON BACH FESTIVAL 2021 Welcome to the 2021 Oregon Bach Festival In times of uncertainty, music is a constant in our lives. Music offers catharsis. It keeps us entertained, conjures memories, and expresses our deepest emotions.Music is everywhere. And during this divisive and tumultuous moment, we’re grateful that music is a powerful and relentless force that universally connects us. As we continue to fight a world-wide pandemic together, OBF invites you to join the global community of music lovers who will listen and watch the 2021 virtual Festival from the comfort and safety of their own spaces.All events are presented free and on-demand. A new concert is posted every day at noon and, unless otherwise noted, will remain available throughout the Festival. Whether you’re watching at home alone or you’re gathered with a socially distanced group of friends for a watch party, we hope you enjoy the 2021 slate of brilliant works. We’ll see you for a return to live music in 2022! June 25 Bach Listening Room with Matt Haimovitz June 25 Dunedin Consort: Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos 5 & 6 June 26 Paul Jacobs: Handel & Bach Recital June 27 To the Distant Beloved with Tyler Duncan June 28 Visions of the Future Part 1: Miguel Harth-Bedoya (48 hours only) June 29 Dunedin Consort: Lagrime Mie June 30 Visions of the Future Part 2: Eric Jacobsen (48 hours only) July 1 Emerson String Quartet July 2 Visions of the Future Part 3: Julian Wachner (48 hours only) July 3 Lara Downes presents -

SYMPHONY No.5 PHILIP GLASS SYMPHONY No.5

SYMPHONY No.5 PHILIP GLASS SYMPHONY No.5 PHILIP GLASS Symphony No. 5 Requiem, Bardo, Nirmanakaya NOVUS NY THE CHOIR OF TRINITY WALL STREET 1. Movement I, Before the Creation DOWNTOWN VOICES 2. Movement II, Creation of the Cosmos TRINITY YOUTH CHORUS 3. Movement III, Creation of Sentient Beings Julian Wachner, conductor 4. Movement IV, Creation of Human Beings 5. Movement V, Love and Joy Heather Buck, soprano 6. Movement VI, Evil and Ignorance Katherine Pracht, mezzo-soprano 7. Movement VII, Suffering Vale Rideout, tenor 8. Movement VII, Compassion Stephen Salters, baritone 9. Movement IX, Death David Cushing, bass 10. Movement X, Judgement and Apocalypse 11. Movement XI, Paradise Recorded May 17 - 20, 2017 12. Movement XII, Dedication of Merit Trinity Church in New York City I. BEFORE THE CREATION II. CREATION OF THE COSMOS There was neither non-existence nor existence then; When He decrees a thing, “White clouds shall float up there was neither realm of space nor the sky which is He but says to it, from the great waters at the border of the world beyond. “Be,” and it is. clustering about the mountain terraces. What stirred? Where? In whose protection? They shall be borne aloft and abroad —The Qur’an 2:117 by the breath of the surpassing soul-beings, Was there water, bottomlessly deep? In the beginning by the breath of the children, There was neither death nor immortality. when God made heaven and earth, they shall be hardened and broken by your cold, There was no sign of night nor of day. the earth was without form and void, shedding downward, in rain-spray, the water of life That One breathed, windless, by Its own impulse. -

21C Liederabend , Op 3

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #21cLiederabend Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer 21c Liederabend, op. 3 Festival of Contemporary Art Song Creative direction by Beth Morrison and Paola Prestini Music direction by Julian Wachner Featuring New York’s finest solo singers, NOVUS NY, and The Choir of Trinity Wall Street BAM Harvey Theater Nov 22 at 7:30pm—Program 1 Nov 23 at 7:30pm—Program 2 Approximate running time: two hours, no intermission Composer in residence Anna Clyne Librettist in residence Royce Vavrek Scenic and lighting design by Maruti Evans BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Projection and video design by S. Katy Tucker Featuring compositions by: Thomas Cabaniss, Christopher Ceronne, Thomas Cipullo, Anna Clyne, Mohammed Fairouz, Judd Greenstein, David Handler, Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Ted Hearne, Marie Incontrera, David T. Little, Tod Machover, Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Major support for music at BAM provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Olga Neuwirth, Paola Prestini, Huang Ruo, Michel van der Aa, Aleksandra Vrebalov, Endowment funding has been provided by Julian Wachner, Eric Whitacre, Du Yun, and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fund for Netsayi & Black Pressure Opera and Music-Theater Co-commisioned and co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects Additional endowment support provided by and VisionIntoArt, presented in association with Trinity Wall the BAM Fund to Support Emerging and Street. Local Musicians 21c Liederabend Op. 3 Being educated in a classical conservatory, the Liederabend (literally “Song Night” and pronounced “leader-ah-bent”) was a major part of our vocal educations. -

“Parisian Spring” at Kennedy Center

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 4, 2016 CONTACT: The Washington Chorus (202) 342-6221 [email protected] The Washington Chorus Presents “Parisian Spring” at Kennedy Center Washington (DC) ‐ On Sunday, May 1, 2016, The Washington Chorus (TWC) will present a concert entitled “Parisian Spring” in which it will celebrate the French aesthetic through the music of French composers Maurice Duruflé, Gabriel Fauré and Louis Vierne, as well as a piece composed by TWC’s Music Director Julian Wachner. The concert will take place at 5:00 PM in the Concert Hall of The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. In addition, the program will feature the renowned organist and composer Thierry Escaich on the Kennedy Center’s Rubenstein Family Organ. Joining on the program will be the Washington National Cathedral Choir of Boys and Girls. Tickets for the concert are priced from $18 - $72 and may be purchased by calling The Washington Chorus Box Office at (202) 342-6221 or ordering securely online at www.thewashingtonchorus.org. Two major works by Maurice Duruflé will bookend the evening. The concert will open with Duruflé’s Messe Cum Jubilo, performed by the men’s sections of the chorus and Mr. Escaich, and will close with the Duruflé Requiem, performed by the entire chorus, Cathedral choir, and Mr. Escaich. Both of these major works, written in 1966 and 1947 respectively, are, like all of Duruflé’s choral works, based on the French Catholic chant tradition which is the basis for the modern French aesthetic. The Requiem, for example, began as a set of organ improvisations based on the Gregorian chants used in the Mass for the Dead. -

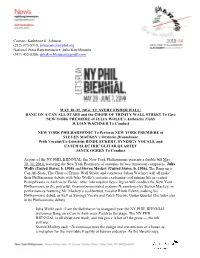

May 30–31, 2014, at Avery Fisher Hall: Bang on a Can

Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] National Press Representative: Julia Kirchhausen (917) 453-8386; [email protected] MAY 30–31, 2014, AT AVERY FISHER HALL: BANG ON A CAN ALL-STARS and the CHOIR OF TRINITY WALL STREET To Give NEW YORK PREMIERE of JULIA WOLFE’s Anthracite Fields JULIAN WACHNER To Conduct NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC To Perform NEW YORK PREMIERE of STEVEN MACKEY’s Oratorio Dreamhouse With Vocalist/Co-Librettist RINDE ECKERT, SYNERGY VOCALS, and CATCH ELECTRIC GUITAR QUARTET JAYCE OGREN To Conduct As part of the NY PHIL BIENNIAL, the New York Philharmonic presents a double bill May 30–31, 2014, featuring the New York Premieres of oratorios by two American composers: Julia Wolfe (United States, b. 1958) and Steven Mackey (United States, b. 1956). The Bang on a Can All-Stars, The Choir of Trinity Wall Street, and conductor Julian Wachner will all make their Philharmonic debuts with Julia Wolfe’s oratorio explaining coal mining life in central Pennsylvania in Anthracite Fields. After intermission Jayce Ogren will conduct the New York Philharmonic in the powerful, Grammy-nominated oratorio Dreamhouse by Steven Mackey, in performances featuring Mr. Mackey’s co-librettist, vocalist Rinde Eckert, making his Philharmonic debut, as well as Synergy Vocals and Catch Electric Guitar Quartet (the latter also in its Philharmonic debut). Julia Wolfe said: “I am thrilled that in its inaugural year the NY PHIL BIENNIAL welcomes Bang on a Can in Anthracite Fields to the stage. The NY PHIL BIENNIAL is all about new work, and this piece is hot off the press — the ink still wet.” Steven Mackey said: “Dreamhouse uses the design and construction of a house as a metaphor for the inevitable fragility of human endeavor. -

Opera Mcgill – Lisl Wirth Black Box Festival November 21, 22, 23 and 24, 2007 Pollack Hall

Schulich School of Music of McGill University Concerts and Publicity 555 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, Quebec H3A 1E3 Phone: (514) 398-5530 Fax: (514) 398-5514 PRESS RELEASE Opera McGill – Lisl Wirth Black Box festival November 21, 22, 23 and 24, 2007 Pollack Hall Albert Herring Benjamin Britten For immediate release November 19, 2007 – Opera McGill opens its 2007-2008 with Albert Herring by Benjamin Britten on November 21, 22, 23 and 24, at 7:30 p.m. in Pollack Hall for its Lisl Wirth Black Box Festival. Tickets for this production are $10 ($5 seniors and students) and are available at the Pollack Hall Box Office, Monday through Friday, 12:00 (noon) to 6:00 p.m., (514) 398-4547. With this production Opera McGill welcomes its new director, Patrick John Hansen, who will stage direct the cast of 13 students, including 3 children. From the orchestra pit, Julian Wachner, Opera McGill’s principal conductor, will conduct the singers and the small ensemble of 13 musicians as indicated by the composer. Comic opera in three acts, Op. 39, by Benjamin Britten to a libretto by Eric Crozier, after Guy de Maupassant’s short story Le rosier de Madame Husson, Albert Herring has been premiered on June 20, 1947 at Glyndebourne by the English Opera Group, an independent and progressive opera company launched by Britten and Crozier, with Peter Pears in the title role and Joan Cross as Lady Billow. “There are a number of themes being played out in this delightful libretto: Victorian fixation on morality, the British pre-occupation with correctness, judging persons strictly on their appearances, sexual repression (or lack thereof) in the countryside of Suffolk in 1900, and how to sever the apron string’s of not only a mother figure but society’s strings as well… Albert Herring is an opera that continues to amuse audience from production to production because of its terrific libretto and Britten’s magnificent genius of a score. -

Some Centennial Events Year 1 (September 1, 2017

Some Centennial Events GeographicalYear 1 (September Events 2017-18 1, 2017 - August 31, 2018) (as of 10/12/2017) Australia 3/22/2018 Neue Oper Wien at Theater an der Wein A Quiet Place, chamber version Adelaide Walter Kobéra, conductor 3/16/2018 Adelaide Symphony Orchestra at Adelaide Festival Theatre Philipp M. Krenn, director Bernstein on Stage!: highlights from West Side Story, On the Town, 3/24/2018 Neue Oper Wien at Theater an der Wein Trouble in Tahiti, Wonderful Town, and Candide. A Quiet Place, chamber version John Mauceri, conductor Walter Kobéra, conductor 3/18/2018 Adelaide Symphony Orchestra at Adelaide Festival Theatre Philipp M. Krenn, director Bernstein on Stage!: highlights from West Side Story, On the Town, Trouble in Tahiti, Wonderful Town, and Candide. 3/24/2018 Tonkunstler Orchestra at Musikverein John Mauceri, conductor Fancy Free Hugh Wolff, conductor 3/28/2018 Adelaide Symphony Orchestra at Adelaide Town Hall Candide Overture 3/25/2018 Neue Oper Wien at Theater an der Wein Guy Noble, conductor & presenter A Quiet Place, chamber version Walter Kobéra, conductor 4/06/2018 Adelaide Symphony Orchestra at Adelaide Town Hall Philipp M. Krenn, director Serenade James Ehnes, violin 3/25/2018 Tonkunstler Orchestra at Musikverein Nicholas Carter, conductor Fancy Free Hugh Wolff, conductor 4/07/2018 Adelaide Symphony Orchestra at Adelaide Town Hall Serenade 3/27/2018 Neue Oper Wien at Theater an der Wein James Ehnes, violin A Quiet Place, chamber version Nicholas Carter, conductor Walter Kobéra, conductor Philipp M. Krenn, director Melbourne 3/29/2018 Neue Oper Wien at Theater an der Wein 8/15/2018 Melbourne Symphony Orchestra at Hamer Hall A Quiet Place, chamber version Symphony No. -

LUNA PEARL WOOLF: Fire and Flood W O NOVUS NY the Choir of Trinity Wall Street Anderson, Elise Quagliata Devon Guthrie, Haimovitzmatt

LUNA PEARL WOOLF: Fire and Flood W O NOVUS NY NY NOVUS Street Wall Trinity The Choir of Elise Quagliata Anderson, Guthrie, Devon Matt Haimovitz Julian Wachner Julian O Nancy Nancy F L O XIN G ALE SERI E S 1 LUNA PEARL WOOLF: Fire and Flood 1 To the Fire 12. 18 For AATBBBs Choir a cappella (1994, rev. 2018) The Choir of Trinity Wall Street Julian Wachner, conductor Après moi, le déluge For Solo Cello and SATB Choir a cappella (2006) 2 NO-AH. The Lord has raised a mighty wind. 7. 10 3 Deep in the water, too deep for tears... 4. 54 4 Gone away and left us, Lord. 6. 09 5 Lord, I’m goin’ down in Louisiana... 6. 17 Matt Haimovitz, cello The Choir of Trinity Wall Street Julian Wachner, conductor 6 Everybody Knows (Leonard Cohen and Sharon Robinson) 5. 05 For Three Female Voices and Cello (arr. 2016) Devon Guthrie, soprano Nancy Anderson, soprano Elise Quagliata, mezzo-soprano Matt Haimovitz, cello Luna Pearl Woolf © Danylo Bobyk Missa in Fines Orbis Terrae 16 Who By Fire (Leonard Cohen) For Choir and Organ (2017) For Three Female Voices and Cello (arr. 2016) 3. 53 7 I. Kyrie 3. 07 Devon Guthrie, soprano 8 II. Sanctus and Benedictus 5. 03 Nancy Anderson, soprano 9 III. Agnus Dei 3. 53 Elise Quagliata, mezzo-soprano The Choir of Trinity Wall Street Matt Haimovitz, cello Avi Stein, organ Julian Wachner, conductor Total playing time: 75. 29 One to One to One For Three Female Voices, Three Cellos and Three Basses (2016) 10 I.