A Fresh Look at Parc Le Breos by David K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Cliffs, Pwll Du and Bishopston Valley Walk

Three Cliffs, Pwll Du and Bishopston Valley Walk Description: A lovely costal walk taking in some of the best south Gower bays before tracking inland up the peaceful Bishopston valley. When you arrive at the bus stop you can text the code swagptp to the number 84268. you will receve a text noitifying you of the departure times of the next buses back to Parkmill. To check times befour you leave timetables are always available at the house or check on www.traveline.info. For those of you not staying with us you are welcome to use this walk but as there are no rights of way through the grounds,please just park and start the walk from the national trust car park in Penmaen. Distance covered: miles Average time: 3 hours Terrain: Easy under foot but Bishopston valley can be very muddy. Directions: Walk out of the front door of the house and turn right, walk past the end of the house and up the corral (fenced in area). Follow the track through the corral and along the old Church path, you will pass the trout ponds on your right, and valley gardens on your left immediately after this there is a cross roads – take the track straight on across the fields and through the woods. At the woodlands end you will cross a style next to a gate, here the track will bear left taking you past a small pink cottage end on to the road and then trough a grassy car park. When you reach the tarmac village lane turn left over the cattle grid. -

Riding on Beaches and Estuaries

ADVICE ON Riding on Beaches and Estuaries 2 There are a number of beaches around England, Wales and Ireland that allow riding and BHS Approved centres that offer the opportunity to ride on a beach. There are many health benefits of riding on a sandy beach for horse and rider. Long sandy stretches are good for building up fitness levels and often the sand can encourage muscle tone and strength. It can provide outstanding views of the sea and is a refreshing way to see areas of beauty throughout the coasts of England, Wales and Ireland. Beach riding can be a wonderful experience for both you and your horse if you are aware of a few points of legality and safety, so please read all the guidance in this leaflet. Estuaries are where rivers meet the sea and they are unpredictable places, requiring caution and respect for the variety of conditions underfoot, the special ecology and the potential risks in riding there. While large expanses of open ground look inviting to riders, some of the conditions encountered may be dangerous. However, with due care and knowledge, estuaries can provide excellent riding opportunities. Is riding on the beach permitted? Check that riding on the beach is permitted. It may be limited to certain times, days or areas and there may be bylaws. Restrictions on time will often be to riders’ benefit, being at quieter periods such as early morning and late evening when there may be fewer other users to avoid. If there are areas where riding is not permitted, be sure you are clear about their extent and avoid them carefully; their boundaries may not be obvious even if they are above high water because signs and fences tend not to last long on the shore or may not be permitted. -

Weatherman Walking Three Cliffs Bay

bbc.co.uk/weathermanwalking © 2017 Weatherman Walking Three Cliffs Bay Approximate distance: 4.5 miles For this walk we’ve included OS grid references should you wish to use them. 1 2 Start End 4 3 N W E S Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database right 2009.All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019855 The Weatherman Walking maps are intended as a guide to help you walk the route. We recommend using an OS map of the area in conjunction with this guide. Routes and conditions may have changed since this guide was written. The BBC takes no responsibility for any accident or injury that may occur while following the route. Always wear appropriate clothing and footwear and check 1 weather conditions before heading out. bbc.co.uk/weathermanwalking © 2017 Weatherman Walking Three Cliffs Bay Start: Gower Heritage Centre, Parkmill Starting ref: SS 543 892 Distance: Approx. 4.5 miles Grade: Leisurely Walk time : 2 hours This delightful circular walk takes us through parkland, woodland, along a beach and up to an old castle high on a hill. Spectacular views abound and the sea air will ensure you sleep well at the end of it! We begin at the Gower Heritage Centre based around a working 12th century water mill where it’s worth spending some time fi nding out about the history of the area before setting off . Directions From the Heritage Centre, cross the ford then take the road to the right. Walk along for about a mile until you come to the entrance to Park Wood (Coed y Parc) on your right. -

Glenside Parkmill | Gower | Swansea | SA3 2EQ GLENSIDE

Glenside Parkmill | Gower | Swansea | SA3 2EQ GLENSIDE “When we first viewed Glenside 30 years ago, we “We worked hard to create a lovely garden which were amazed at the size of the house and the is very private and quiet. It offers protection from land. We thought that it was too good to be true! the elements and even now after 30 years, I will We knew that there would be a few things to fix leave the house with no coat and quickly realise up, but we could see the potential and have that it was a mistake! The patio is a relaxing created a lovely, large family home in a unique sun trap and it’s a great garden for children to location,” say the vendors. explore, climb trees and build dens.” “We’ve made a number of changes over the “We tend to spend most of our time in the years to Glenside, including new roofs, refurbished kitchen / dining area. We are always very throughout, new kitchens, bathrooms and a number comfortable and happy in this part of the house. of extensions extending the reception rooms and The front room is also very nice, and we like upstairs creating a walk in wardrobe and en-suite to relax in there with a glass of wine at the for the master bedroom. We have updated the weekend.” central heating and gas fires. We have made Glenside work very well for us as a family.” “We enjoy easy access to the beach, Gower and Swansea. It’s very quiet, yet everything we need is “The location is fabulous. -

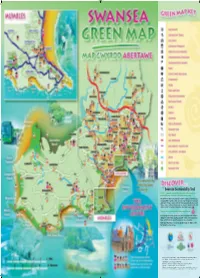

Swansea Sustainability Trail a Trail of Community Projects That Demonstrate Different Aspects of Sustainability in Practical, Interesting and Inspiring Ways

Swansea Sustainability Trail A Trail of community projects that demonstrate different aspects of sustainability in practical, interesting and inspiring ways. The On The Trail Guide contains details of all the locations on the Trail, but is also packed full of useful, realistic and easy steps to help you become more sustainable. Pick up a copy or download it from www.sustainableswansea.net There is also a curriculum based guide for schools to show how visits and activities on the Trail can be an invaluable educational resource. Trail sites are shown on the Green Map using this icon: Special group visits can be organised and supported by Sustainable Swansea staff, and for a limited time, funding is available to help cover transport costs. Please call 01792 480200 or visit the website for more information. Watch out for Trail Blazers; fun and educational activities for children, on the Trail during the school holidays. Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey Digital Map with the permission of the Controller of H.M.S.O. Crown Copyright - City & County of Swansea • Dinas a Sir Abertawe - Licence No. 100023509. 16855-07 CG Designed at Designprint 01792 544200 To receive this information in an alternative format, please contact 01792 480200 Green Map Icons © Modern World Design 1996-2005. All rights reserved. Disclaimer Swansea Environmental Forum makes makes no warranties, expressed or implied, regarding errors or omissions and assumes no legal liability or responsibility related to the use of the information on this map. Energy 21 The Pines Country Club - Treboeth 22 Tir John Civic Amenity Site - St. Thomas 1 Energy Efficiency Advice Centre -13 Craddock Street, Swansea. -

NLCA39 Gower - Page 1 of 11

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA39 GOWER © Crown copyright and database rights 2013 Ordnance Survey 100019741 Penrhyn G ŵyr – Disgrifiad cryno Mae Penrhyn G ŵyr yn ymestyn i’r môr o ymyl gorllewinol ardal drefol ehangach Abertawe. Golyga ei ddaeareg fod ynddo amrywiaeth ysblennydd o olygfeydd o fewn ardal gymharol fechan, o olygfeydd carreg galch Pen Pyrrod, Three Cliffs Bay ac Oxwich Bay yng nglannau’r de i halwyndiroedd a thwyni tywod y gogledd. Mae trumiau tywodfaen yn nodweddu asgwrn cefn y penrhyn, gan gynnwys y man uchaf, Cefn Bryn: a cheir yno diroedd comin eang. Canlyniad y golygfeydd eithriadol a’r traethau tywodlyd, euraidd wrth droed y clogwyni yw bod yr ardal yn denu ymwelwyr yn eu miloedd. Gall y priffyrdd fod yn brysur, wrth i bobl heidio at y traethau mwyaf golygfaol. Mae pwysau twristiaeth wedi newid y cymeriad diwylliannol. Dyma’r AHNE gyntaf a ddynodwyd yn y Deyrnas Unedig ym 1956, ac y mae’r glannau wedi’u dynodi’n Arfordir Treftadaeth, hefyd. www.naturalresources.wales NLCA39 Gower - Page 1 of 11 Erys yr ardal yn un wledig iawn. Mae’r trumiau’n ffurfio cyfres o rostiroedd uchel, graddol, agored. Rheng y bryniau ceir tirwedd amaethyddol gymysg, yn amrywio o borfeydd bychain â gwrychoedd uchel i gaeau mwy, agored. Yn rhai mannau mae’r hen batrymau caeau lleiniog yn parhau, gyda thirwedd “Vile” Rhosili yn oroesiad eithriadol. Ar lannau mwy agored y gorllewin, ac ar dir uwch, mae traddodiad cloddiau pridd a charreg yn parhau, sy’n nodweddiadol o ardaloedd lle bo coed yn brin. Nodwedd hynod yw’r gyfres o ddyffrynnoedd bychain, serth, sy’n aml yn goediog, sydd â’u nentydd yn aberu ar hyd glannau’r de. -

2016 Directory the Dragon Hotel the Kingsway, Swansea SA1 5LS 01792 657100 [email protected] 4★H, 4★ H

2016 Directory The Dragon Hotel The Kingsway, Swansea SA1 5LS 01792 657100 www.dragon-hotel.co.uk [email protected] 4★H, 4★ H Serviced Accommodation Morgans Hotel Somerset Place, Swansea SA1 1RR 01792 484848 www.morganshotel.co.uk [email protected] 4★ H Self Catering Accommodation Caravan & Camping Somerfield Lodge B & B Clyne Golf Club, 118-120 Owls Lodge Lane, Mayals, Swansea SA3 5DP 01792 929293 www.somerfieldlodge.co.uk [email protected] 4★★GA Attractions & Activities Swansea Marriott Hotel Maritime Quarter, Swansea SA1 3SS 01792 642020 Food & Drink www.swanseamarriott.co.uk [email protected] 4★ H Travel Campus Accommodation, Swansea University Singleton Park, Swansea SA2 8PP 01792 295665 www.swansea.ac.uk/conferences [email protected] 3 - 4★ CA Abbreviations Accommodation Type Beachcomber 364 Oystermouth Road, Swansea SA1 3UL 01792 651380 AG Awaiting Grading AA Alternative Accommodation www.beachcomberguesthouse.com [email protected] 3★ GH APP Approved AcA Activity Accommodation BH Budget Hotel B Bunkhouse Mercure Swansea Phoenix Way, Swansea SA7 9EG 01792 310330 L Listed BB Bed & Breakfast www.mercure.com [email protected] 3★ H SP Service Provider CA Campus Accommodation ★ Visit Wales Grading F Farmhouse Village The Hotel Club Swansea Langdon Road, SA1 Waterfront, Swansea SA1 8QY 01792 341270 ★ AA grading GA Guest Accommodation www.village-hotels.com [email protected] Listed u AA grading for GpA Group Accommodation caravan parks -

The New Gower Hotel, Bishopston, Swansea Www. Thenewgowerhotel.Wales/Weddings 01792 234111 [email protected]

The New Gower Hotel, Bishopston, Swansea www. thenewgowerhotel.wales/weddings 01792 234111 [email protected] We are delighted that you are considering The New Gower Hotel to be part of your very special day. We would welcome the opportunity to meet you and show you around our beautiful luxury boutique hotel for your wedding. In the meantime, browse through our wedding pack to get an idea of what we have to offer. Contained within this pack are example packages available to you. Every couple is unique and so your wedding day will be too, therefore, all our packages can be personalised to suit you. This pack will give you a guide to what is available with something to suit each budget and style. Our Celebration Suite is licensed for civil ceremonies and can accommodate up to 150 guests, so whether you plan to have a small intimate wedding or have a larger gathering, The New Gower Hotel can accommodate. The New Gower Hotel, Bishopston, Swansea www. thenewgowerhotel.wales/weddings 01792 234111 [email protected] We are a 13-bedroom boutique hotel situated in Bishopston at the heart of Gower surrounded by countryside and a short drive from the coast line. The hotel is conveniently located next to the beautiful and historic 13th Century, St Teilo’s church and is ideal for those wanting a traditional religious ceremony. For those, preferring a civil ceremony, our celebration suite is fully licensed to hold ceremonies and is included in all packages. Our location really does alleviate the hassle of transportation on your wedding day, allowing you and your guests to really relax and enjoy this very special occasion. -

Service 118 SWANSEA to RHOSSILI - Services Services

time Service 118 SWANSEA to RHOSSILI - services services via Uplands, Sketty, Killay, Upper Killay, Parkmill, Reynoldston & Port Eynon - QR code code QR Sundays & Bank Holiday Mondays (18th July to 30th August 2021 inclusive) SWANSEA (City Bus Station) 0905 1035 1205 1335 1505 1605 Uplands (Post Office) 0914 1044 1214 1344 1514 1614 or scan the scan or Sketty Cross (Lloyds Bank) 0918 1048 1218 1348 1518 1618 phone smart with your Gower Road (Jctn Glan-yr-Afon Road) 0920 1050 1220 1350 1520 1620 Olchfa School 0922 1052 1222 1352 1522 1622 www.natgroup.co.uk/bus Killay (Black Boy) 0925 1055 1225 1355 1525 1625 visit please information passenger Upper Killay (Community Centre) 0929 1059 1229 1359 1529 1629 Swansea Airport (Main Entrance) 0933 1103 1233 1403 1533 1633 For full timetables, ticketing, and real and ticketing, timetables, full For Parkmill (Shepherds & Gower Heritage Centre) 0938 1108 1238 1408 1538 1638 Penmaen Church 0941 1111 1241 1411 1541 1641 Towers 0946 1116 1246 1416 1546 1646 Reynoldston (Police Station) 0948 1118 1248 1418 1548 1648 Knelston 0951 1121 1251 1421 1551 1651 Scurlage 0954 1124 1254 1424 1554 1654 Port Eynon 0959 1129 1259 1448* 1559 1718* Scurlage 1004 1134 1304 1424 1604 1654 RHOSSILI 1012 1142 1312 1432 1612 1702 RHOSSILI 1015 1145 1315 1435 1705 1705 Scurlage 1023 1153 1323 1443 1713 1713 Port Eynon 0959* 1129* 1259* 1448 1718 1718 Scurlage 1023 1153 1323 1453 1723 1723 Knelston 1026 1156 1326 1456 1726 1726 Reynoldston (Police Station) 1029 1159 1329 1459 1729 1729 Towers 1031 1201 1331 1501 1731 1731 -

Gower Commons

Gower Commons Successional Health Check Report to the Gower Landscape Partnership 2018 Brackenbury, S & Jones, G (2018) Gower Commons - Successional Health Check The authors wish to thank the many individuals and organisation which gave their help, expertise, data and support to the drawing up of this report, including the City and Council of Swansea, the National Trust, Natural Resources Wales and the Welsh Government. Particular thanks go to the commoners of Gower and especially the Gower Commoners Association, without whose guidance and records this work would have been next to impossible. Needless to say, we don’t claim to speak for any of these organisations or individuals and all errors are our own. This report is part of the City and Council of Swansea Heritage Lottery funded Gower Landscape Project and is co-funded by Esmée Fairbairn Foundation through the Foundation for Common Land. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the funders. Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................... 5 2. INTRODUCTION TO GOWER ............................................................................................... 6 3. COMMON LAND ................................................................................................................. 8 4. THE GOWER COMMONS AND THE GOWER COMMONERS -

History Programme of Study

Historical Gower Key Stage 2 Park Wood Education Resource Notes for Teachers Contents Page Information for Teachers 1 How to use this pack 1 Risk Assessment 1 Equipment List 2 Curriculum Links 2 Cross - curricular work 3 Before you go activities 4 After your visit activities 4 Activities 1. Park Wood (Parc le Breos) 5 2. Giants Grave 6 3. Cathole Cave 7 4. Park Wood limekiln and quarries 8 Park Wood trail leaflet 9 Credits This education pack was written and designed by Audio Trails Ltd (www.audiotrails.co.uk) on behalf of Gower Landscape Partnership. The Gower Landscape Project has received funding through the Rural Development Plan for Wales 2007-2013, which is funded by the Welsh Government and the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, and also from the Heritage Lottery Fund under its Landscape Partnership programme. Other funding partners include the City & County of Swansea, Natural Resources Wales and The National Trust. Images were supplied and are copyright of the following individuals and organisations: Audio Trails Ltd © Copyright GGAT HER Charitable Trust Helen Grey Information for teachers Gower’s rich varied landscape has made it an attractive environment for human occupation since at least c 123,000 BC. The peninsula has been home to Stone Age hunter-gatherers, Iron Age farmers and warriors, early Christian immigrants and Norman knights. This part of the Gower app around Park Wood explores the theme ‘Historical Gower’. The trail has four stops: Giants Grave, Cathole Cave, Limekiln and quarries and Parc le Breos. At each stop oral histories, stories, photographs, facts and information are used to reveal the areas fascinating historical past. -

Programme – Swansea Ramblers We Offer Enjoyable Short & Long Walks

Programme – Swansea Ramblers We offer enjoyable short & long walks all year around and welcome new walkers to try a walk with us. 1 Front Cover Photograph: A Ramblers’ visit to Llanmadoc Church v23 2 About Swansea Ramblers Swansea Ramblers, (originally West Glamorgan Ramblers) was formed in 1981. We always welcome new walkers to share our enjoyment of the countryside, socialise and make new friends. We organise long and short walks, varying from easy to strenuous across a wide area of South and Mid Wales, including Gower and Swansea. Swansea Ramblers Website: www.swansearamblers.org.uk On the website, you’ll find lots of interest and photographs of previous walks. For many new members, this is their first introduction to our group and part of the reason they choose to walk with us. Programme of walks: We have walks to suit most tastes. The summer programme runs from April to September and the winter programme covers October to March. A copy of the programme is supplied to members and can be downloaded from our website. Evening short walks: These are about 2-3 miles and we normally provide these popular walks once a week in the summer. Monday Short walks: These are 2-3 mile easier walks as an introduction to walking and prove popular with new walkers. Weekday walks: We have one midweek walk each week. The distance can vary from week to week, as can the day on which it takes place. Saturday walks: We have a Saturday walk every week that is no more than 6 miles in length and these are a great way to begin exploring the countryside.