Gower Commons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Due to CV-19, It Is Not Going to Be Practical for the Community Council

HERE IS A LIST OF LOCAL SERVICES THAT ARE OPEN OR WILL DELIVER FOOD AND PET If any member of our community needs any form of help, for shopping and SUPPLIES pharmacy items, the Community Council have set up a team to help with Name Contact this. It is being co-ordinated by 3 Community Councillors and you can contact Heronsway Garage & post office open Deliveries through volunteers. Please ring Cllr Jo Gooding them on: usual hours who will co-ordinate this 07989214487 (if no answer please leave a message and she’ll ring you back) Jo Gooding – 0798921487 Shepherds (fruit and veg) Don’t phone. Deliveries only through Facebook messenger. Sam Hughes – 07917704926 Moranda Matthews – 07903335154 Gower coast meat (Gower raised meat) Deliveries only 07939378084 Please leave a message if you do not get an answer. Please don’t be afraid Brian Davies Country Stores (Agri and Deliveries available 01792 875050 to ring for any help you need or feel a neighbour may need. domestic animal food suppliers) open Stay safe everyone and follow the guidance on the Gov.UK website, the Crofty supermarket (Grocery shop + Deliveries to Crofty and Llanrhidian min order £20 01792 post office) open 850258 Welsh Government website Gov.Wales and the NHS website NHS.UK Llanmadoc shop (Grocery shop) open Delivering to Landimore, Llangennith, Burry Green, 10am-1.00pm Cheriton only. 01792 386494 Due to CV-19, it is not going to be practical for the Community Council to hold their April meeting, we will place on the website or Facebook King’s Head pub closed Deliveries min order £25 or pick up 01792386212 (Please see Facebook page for menu) page anything that may be of interest. -

Dart18europeans

AUGUST 16TH - 22ND rt18euro da peans 2014 .org WELCOME CROESO A big warm welcome to one and all from The Mumbles Yacht Club and we hope you have a fantastic week both on and off the water. Our team has been working tirelessly for months to put this all together and I’m sure that it will be a memorable event for everyone involved. If you need, or are not sure of anything during your stay please don’t be shy - just ask, this whole week is part of all of our hols and is therefore meant to be fun and hassle free. May I just say a big thank you to the City and County of Swansea for their support, without which none of this would be possible, and also to ALL of our sponsors for their contributions enabling us to develop a packed programme both on and off the water. Welcome ashore... From peaceful retreats, to family fun, to energetic Again, Welcome and Enjoy. Visit the largest collection outdoor adventures, we have the best holiday of holiday homes in accomodation to suit your needs, all managed by Mumbles, Gower Gower’s most experienced locally-based agency. Chris Osborne Visit our website or give us a call. One of our Commodore & Swansea Marina dedicated local team will be happy to help. ( Dart 7256 ) OVER mumblesyachtclub.co.uk 2 Tel +44 (0) 1792 360624 | [email protected] | www.homefromhome.com 101 Newton Road, Mumbles, Swansea, SA3 4BN MUMBLES - the club that likes to say YES! special offer It was the Welsh Open Dart 18 Championships 2013. -

Welsh Bulletin

BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF THE BRITISH ISLES WELSH BULLETIN Editors: R. D. Pryce & G. Hutchinson No. 76, June 2005 Mibora minima - one oftlle earliest-flow~ring grosses in Wales (see p. 16) (Illustration from Sowerby's 'English Botany') 2 Contents CONTENTS Editorial ....................................................................................................................... ,3 43rd Welsh AGM, & 23rd Exhibition Meeting, 2005 ............................ " ............... ,.... 4 Welsh Field Meetings - 2005 ................................... " .................... " .................. 5 Peter Benoit's anniversary; a correction ............... """"'"'''''''''''''''' ...... "'''''''''' ... 5 An early observation of Ranunculus Iriparlitus DC. ? ............................................... 5 A Week's Brambling in East Pembrokeshire ................. , ....................................... 6 Recording in Caernarfonshire, v.c.49 ................................................................... 8 Note on Meliltis melissophyllum in Pembrokeshire, v.c. 45 ....................................... 10 Lusitanian affinities in Welsh Early Sand-grass? ................................................... 16 Welsh Plant Records - 2003-2004 ........................... " ..... " .............. " ............... 17 PLANTLIFE - WALES NEWSLETTER - 2 ........................ " ......... , ...................... 1 Most back issues of the BSBI Welsh Bulletin are still available on request (originals or photocopies). Please enquire before sending cheque -

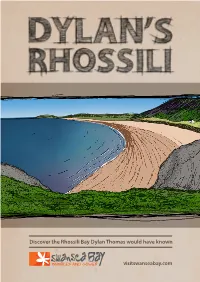

Discover the Rhossili Bay Dylan Thomas Would Have Known

Discover the Rhossili Bay Dylan Thomas would have known visitswanseabay.com ‘I wish I was in schoolfriend Guido Heller ran the Worm’s Head Hotel, but at the time it Rhossili’… did not have a licence. …wrote poet and writer Dylan Thomas (when he was pining to be back home). More about Dylan And you can certainly see why; Rhossili Bay is, as Dylan also aptly put, a ‘very Many people are familiar with Dylan’s long golden beach’ on the Gower poetry and prose, some of which is Peninsula, which was the first in the influenced by Gower’s inspirational UK to be designated as an Area of countryside and coastal scenery; Outstanding Natural Beauty. but this summer, there is a unique opportunity to see some of Dylan’s A ‘VERY LONG GOLDEN personal letters and manuscripts, BEACH’ ON THE GOWER written in his own hand at an PENINSULA exceptional exhibition at Swansea’s Dylan Thomas Centre. Dylan Thomas spent his boyhood in Swansea and enjoyed camping on INFLUENCED BY Gower as depicted in his short story GOWER’S INSPIRATIONAL ‘Extraordinary Little Cough’. The COUNTRYSIDE AND COASTAL promontory of Worm’s Head is linked SCENERY to the mainland by a tidal causeway and Dylan was apt to mistime his return This exhibition is part of Dylan Thomas and get cut off by the tide – resulting 2014, a year-long celebration of his in an impromptu overnight stay on life and work in his hometown and the Worm! He writes about this in the surrounding area. story ‘Who Do You Wish Was With Us?’. -

A TIME for May/June 2016

EDITOR'S LETTER EST. 1987 A TIME FOR May/June 2016 Publisher Sketty Publications Address exploration 16 Coed Saeson Crescent Sketty Swansea SA2 9DG Phone 01792 299612 49 General Enquiries [email protected] SWANSEA FESTIVAL OF TRANSPORT Advertising John Hughes Conveniently taking place on Father’s Day, Sun 19 June, the Swansea Festival [email protected] of Transport returns for its 23rd year. There’ll be around 500 exhibits in and around Swansea City Centre with motorcycles, vintage, modified and film cars, Editor Holly Hughes buses, trucks and tractors on display! [email protected] Listings Editor & Accounts JODIE PRENGER Susan Hughes BBC’s I’d Do Anything winner, Jodie Prenger, heads to Swansea to perform the role [email protected] of Emma in Tell Me on a Sunday. Kay Smythe chats with the bubbly Jodie to find [email protected] out what the audience can expect from the show and to get some insider info into Design Jodie’s life off stage. Waters Creative www.waters-creative.co.uk SCAMPER HOLIDAYS Print Stephens & George Print Group This is THE ultimate luxury glamping experience. Sleep under the stars in boutique accommodation located on Gower with to-die-for views. JULY/AUGUST 2016 EDITION With the option to stay in everything from tiki cabins to shepherd’s huts, and Listings: Thurs 19 May timber tents to static camper vans, it’ll be an unforgettable experience. View a Digital Edition www.visitswanseabay.com/downloads SPRING BANK HOLIDAY If you’re stuck for ideas of how to spend Spring Bank Holiday, Mon 30 May, then check out our round-up of fun events taking place across the city. -

The Penthouse – Langland

Local Attractions Find us The historic village of Mumbles has many good restarants, Leave the M4 at J42 following the A483 to Swansea. Cross- cafés and cosy pubs. ing the river approaching the city centre this becomes the The Penthouse The Gower Peninsula, Britain’s first Area of Outstaning A4067. Follow this for 4 miles around beautiful Swansea Bay Langland Bay, Gower Natural Beauty is a haven for lovers of nature and the to the village of Mumbles. outdoors. We are lucky to have some of the country’s Turn right at the mini-roundabout on the edge of the village finest beaches, coastal walks, wildlife habitats and a onto Newton Road for 0.3 miles then left at traffic lights onto fascinating history. Langland road for 0.7 miles. Ignore the first left turn sign- For sports lovers there are tennis courts, golf, horse riding, posted Langland Bay. The road bends sharply to the right surfing and other water sports. Nearby Swansea has a well just before a prominent church, take the immediate left on equipped leisure centre, theatre, cinema, museums and the bend onto Brynfield Road. galleries. For the more adventurous, Gower has abundant After 60m take the first left, Langland Court Road, and the climbing and nearby Afan Valley boasts world class first left again. Follow the road for 150m then bear right onto mountain bike trails. a private lane to the Woodridge Court car park. The Penthouse, Woodridge Court, Langland, Swansea SA3 4TH Rhosilli Swansea Bracelet Bay Three Cliffs Relax... Unwind... Luxury Bookings / Contact www.gowerpenthouse.com Stella on 01792 824350 [email protected] Visit our website to join our mailing list or like us on Facebook for excu- sive offers and late availability deals. -

Geographical Indications: Gower Salt Marsh Lamb

SPECIFICATION COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 1151/2012 on protected geographical indications and protected designations of origin “Gower Salt Marsh Lamb” EC No: PDO (X) PGI ( ) This summary sets out the main elements of the product specification for information purposes. 1 Responsible department in the Member State Defra SW Area 2nd Floor Seacole Building 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Tel: 02080261121 Email: [email protected] 2 Group Name: Gower Salt Marsh Lamb Group Address: Weobley Castle, Llanrhidian Gower SA3 1HB Tel.: 01792 390012 e-mail:[email protected] Composition: Producers/processors (6) Other (1) 3 Type of product Class 1.1 Fresh Meat (and offal) 4 Specification 4.1 Name: ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ 4.2 Description: ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ is prime lamb that is born reared and slaughtered on the Gower peninsular in South Wales. It is the unique vegetation and environment of the salt marshes on the north Gower coastline, where the lambs graze, which gives the meat its distinctive characteristics. ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ is a natural seasonal product available from June until the end of December. There is no restriction on which breeds (or x breeds) of sheep can be used to produce ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’. However, the breeds which are the most suitable, are hardy, lighter more agile breeds which thrive well on the salt marsh vegetation. ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ is aged between 4 to 10 months at time of slaughter. All lambs must spend a minimum of 2 months in total, (and at least 50% of their life) grazing the salt marsh although some lambs will graze the salt marsh for up to 8 months. -

Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn Diaries Vol 6

The Dillwyn Collection The Journals of Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn (b.1814 d.1892) Transcribed by Richard Morris ©Richard Morris and the family of Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn The unpublished journals of Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn from 1833 to 1892 have been transcribed by Richard Morris and are made available for academic and research use. Copyright in the diaries remains with the family and requests for other use or further publication should be made to the address below. Note: This is a working edition of the journals that have been transcribed over a number of years by Richard Morris. This edition includes inconsistencies in presentation and orthography – in part due to inconsistencies in the originals. This work is presented to aid research into the Dillwyn family and related topics. It is part of an ongoing project that aims in the future to bring together a number of diaries and to convert them to modern, marked-up formats that will allow more powerful features and searching. For further information on this and other collections please visit: www.swansea.ac.uk/lis/historicalcollections Contact Information: Archives Library and Information Services Swansea University Singleton Park Swansea SA2 8PP [email protected] January 1841 Burrows Lodge Friday 1st Weather showery – Saturday 2 W. still rather showery Sunday 3 Wind high. North West – cold with slight Storms of Snow Monday 4 Snow fell in the night. very cold Wind NE. I went with LWD & J.D.L. to Pyle to a special sessions to decide whether Barristers or Attorneys should practice at Quarter Sessions – it was determined by a division of 10 to 6 that the present practice viz that of the Attorneys be continued – Tuesday 5 Very cold. -

Baytrans Web Walks

COASTAL RAMBLE: LLANMADOC – LLANRHIDIAN An interesting walk hugging the coastline and Llanrhidian Salt Marshes The northern part of Gower is quite different from the dramatic cliff and beach scenery of the south – this is a gentle coastline dominated by the wide expanse of the Loughor Estuary, by mud flats and salt marshes. Notably, Llanrhidian Marsh is an internationally recognised wildlife and bird habitat. Passing scattered hamlets and old farms, and at Weobley Castle, this section of the coast path links three very characteristic north Gower villages. The Walk in detail The Coast Path does not come through Llanmadoc as it detours some kilometres to the north via Whiteford Point. For this walk, alight at the Britannia Inn (GR 439934) and walk up the hill towards the village for 50 metres, turning into a cul-de-sac leading to a farm track joining the Coast Path at Pill Cottage. Turn right here* and skirt Landimore Marsh to seaward and North Hill Tor to landward. *At high tide, the section across Llanmadoc Pill may become impassable. Retrace steps to Llanmadoc then via Cheriton/North Hills Farm to re-join path at GR 454938) The path follows a level course below the steep cliffs through the hamlet of Landimore (GR 465934). From here it turns inland for about 200 metres, then left through a wicket gate leading through several fields before becoming a grassy path below Hambury Wood, a local nature reserve notable for its birdlife. Fortunately, there is very good signposting along this section which is devoid of clear landmarks. Weobley Castle appears ahead in its commanding location and the Coast Path soon bisects a causeway leading from the road two kms out into Llanrhidian Marsh. -

Weatherman Walking Three Cliffs Bay

bbc.co.uk/weathermanwalking © 2017 Weatherman Walking Three Cliffs Bay Approximate distance: 4.5 miles For this walk we’ve included OS grid references should you wish to use them. 1 2 Start End 4 3 N W E S Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database right 2009.All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019855 The Weatherman Walking maps are intended as a guide to help you walk the route. We recommend using an OS map of the area in conjunction with this guide. Routes and conditions may have changed since this guide was written. The BBC takes no responsibility for any accident or injury that may occur while following the route. Always wear appropriate clothing and footwear and check 1 weather conditions before heading out. bbc.co.uk/weathermanwalking © 2017 Weatherman Walking Three Cliffs Bay Start: Gower Heritage Centre, Parkmill Starting ref: SS 543 892 Distance: Approx. 4.5 miles Grade: Leisurely Walk time : 2 hours This delightful circular walk takes us through parkland, woodland, along a beach and up to an old castle high on a hill. Spectacular views abound and the sea air will ensure you sleep well at the end of it! We begin at the Gower Heritage Centre based around a working 12th century water mill where it’s worth spending some time fi nding out about the history of the area before setting off . Directions From the Heritage Centre, cross the ford then take the road to the right. Walk along for about a mile until you come to the entrance to Park Wood (Coed y Parc) on your right. -

2013 02 05 Gower Commons Tiroedd Comin Gwyr SAC Management

CYNGOR CEFN GWLAD CYMRU COUNTRYSIDE COUNCIL FOR WALES CORE MANAGEMENT PLAN INCLUDING CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES FOR GOWER COMMONS SAC (SPECIAL AREA OF CONSERVATION) Version: 15 Date: 20 April 2011 (Minor map edit, February 2013) Approved by: Charlotte Gjerlov More detailed maps of management units can be provided on request. A Welsh version of all or part of this document can be made available on request. CONTENTS Preface: Purpose of this document 1. Vision for the Site 2. Site Description 2.1 Area and Designations Covered by this Plan 2.2 Outline Description 2.3 Outline of Past and Current Management 2.4 Management Units 3. The Special Features 3.1 Confirmation of Special Features 3.2 Special Features and Management Units 4. Conservation Objectives Background to Conservation Objectives 4.1 Conservation Objective for Feature 1: Northern Atlantic wet heaths with Erica tetralix 4.2 Conservation Objective for Feature 2: European dry heath 4.3 Conservation Objective for Feature 3: Molinia meadows on calcareous, peaty or clayey-silt-laden soils ( Molinia caeruleae) 4.4 Conservation Objective for Feature 4: Southern damselfly 4.5 Conservation Objective for Feature 5: Marsh fritillary butterfly 5. Assessment of Conservation Status and Management Requirements: 5.1 Conservation Status and Management Requirements of Feature 1: Northern Atlantic wet heaths with Erica tetralix 5.2 Conservation Status and Management Requirements of Feature 2: European dry heath 5.3 Conservation Status and Management Requirements of Feature 3: Molinia meadows on calcareous, peaty or clayey-silt-laden soils ( Molinia caeruleae) 5.4 Conservation Status and Management Requirements of Feature 4: Southern damselfly 5.5 Conservation Status and Management Requirements of Feature 5: Marsh fritillary butterfly 6. -

London House, Beach Road, Penclawdd, Swansea

London House, Beach Road, Penclawdd, Swansea. Archaeological Building Investigation & Recording By Richard Scott Jones (BA, MA, MCIfA) May 2019 HRSWales Report No: 208 Archaeological Building Investigation & Recording London House, Beach Road, Penclawdd, Swansea. By Richard Scott Jones (BA Hons, MA, MCIfA) Prepared for: Mr Adam Rewbridge J.A. Rewbridge Development Services 5 Chapel Street Mumbles Swansea SA3 4NH On behalf of: Mr and Mrs Banfield Date: May 2019 HRSW Report No: 208 H e r i t a g e Recording Services Wales Egwyl, Llwyn-y-groes, Tregaron, Ceredigion SY25 6QE Tel: 01570 493759 Fax: 08712 428171 E-mail: [email protected] Contents i) List of Illustrations and Photo plates Executive Summary Page i 1. Introduction Page 01 2. Methodology and Consultations Page 02 Appendix I: Figures Appendix II: Photo plates Appendix III: Archive Cover Sheet Copyright Notice: Heritage Recording Services Wales retain copyright of this report under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, and have granted a licence to the Mr and Mrs Banfield to use and reproduce the material contained within. The Ordnance Survey have granted Heritage Recording Services Wales a Copyright Licence (No. 100052823) to reproduce map information; Copyright remains otherwise with the Ordnance Survey. i) List of Illustrations Figures Fig 01: Location map (OS Landranger 50,000). Fig 02: Location Map (OS Explorer 1:25,000). Fig 03: Location Block Plan Fig 04: Existing Elevations and Floor Plans Fig 05: Penclawdd Conservation Area Fig 06: Photo Index Plan Photo Plates