Musical News: Popular Music in Political Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“WOODY” GUTHRIE July 14, 1912 – October 3, 1967 American Singer-Songwriter and Folk Musician

2012 FESTIVAL Celebrating labour & the arts www.mayworks.org For further information contact the Workers Organizing Resource Centre 947-2220 KEEPING MANITOBA D GOING AN GROWING From Churchill to Emerson, over 32,000 MGEU members are there every day to keep our province going and growing. The MGEU is pleased to support MayWorks 2012. www.mgeu.ca Table of ConTenTs 2012 Mayworks CalendaR OF events ......................................................................................................... 3 2012 Mayworks sChedule OF events ......................................................................................................... 4 FeatuRe: woody guthRie ............................................................................................................................. 8 aCKnoWledgMenTs MAyWorkS BoArd 2012 Design: Public Service Alliance of Canada Doowah Design Inc. executive American Income Life Front cover art: Glenn Michalchuk, President; Manitoba Nurses Union Derek Black, Vice-President; Mike Ricardo Levins Morales Welfley, Secretary; Ken Kalturnyk, www.rlmarts.com Canadian Union of Public Employees Local 500 Financial Secretary Printing: Members Transcontinental Spot Graphics Canadian Union of Public Stan Rossowski; Mitch Podolak; Employees Local 3909 Hugo Torres-Cereceda; Rubin MAyWorkS PuBLIcITy MayWorks would also like to thank Kantorovich; Brian Campbell; the following for their ongoing Catherine Stearns Natanielle Felicitas support MAyWorkS ProgrAMME MAyWorkS FundErS (as oF The Workers Organizing Resource APrIL -

Examining the Use of Theatre Among Children and Youth in U.S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School November 2019 Mini-Actors, Mega-Stages: Examining the Use of Theatre among Children and Youth in U.S. Evangelical Megachurches Carla Elisha Lahey Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lahey, Carla Elisha, "Mini-Actors, Mega-Stages: Examining the Use of Theatre among Children and Youth in U.S. Evangelical Megachurches" (2019). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5101. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5101 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. MINI-ACTORS, MEGA-STAGES: EXAMINING THE USE OF THEATRE AMONG CHILDREN AND YOUTH IN U.S. EVANGELICAL MEGACHURCHES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Theatre by Carla Elisha Lahey B.A., Samford University, 2000 M.S., Florida State University, 2012 December 2019 Acknowledgements For the past three years of this project, I have been dreaming of writing this page. Graduate school has not the easiest path, but many people walked along the road with me. I have looked forward to completing this project so I could thank them within the pages they helped to make possible. -

On the Streets of San Francisco for Justice PAGE 8

THE VOICE OF THE UNION April b May 2016 California Volume 69, Number 4 CALIFORNIA TeacherFEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFT, AFL-CIO STRIKE! On the streets of San Francisco for justice PAGE 8 Extend benefits Vote June 7! A century of of Prop. 30 Primary Election workers’ rights Fall ballot measure opportunity Kamala Harris for U.S. Senate Snapshot: 100 years of the AFT PAGE 3 PAGE 5 PAGE 7 California In this issue All-Union News 03 Community College 14 Teacher Pre-K/K-12 12 University 15 Classified 13 Local Wire 16 UpFront Joshua Pechthalt, CFT President Election 2016: Americans have shown they that are ready for populist change here is a lot at stake in this com- But we must not confuse our elec- message calling out the irresponsibil- Ting November election. Not only toral work with our community build- ity of corporate America. If we build will we elect a president and therefore ing work. The social movements that a real progressive movement in this shape the Supreme Court for years to emerged in the 1930s and 1960s weren’t country, we could attract many of the Ultimately, our job come, but we also have a key U.S. sen- tied to mainstream electoral efforts. Trump supporters. ate race, a vital state ballot measure to Rather, they shaped them and gave In California, we have changed is to build the social extend Proposition 30, and important rise to new initiatives that changed the the political narrative by recharging state and local legislative races. political landscape. Ultimately, our job the labor movement, building ties movements that keep While I have been and continue is to build the social movements that to community organizations, and elected leaders to be a Bernie supporter, I believe keep elected leaders moving in a more expanding the electorate. -

The Walls of Spain: Diary of a Short-Term Mission ©2009 by JD

Excerpt from: The Walls of Spain: Diary of a Short-Term Mission ©2009 by J.D. Alcala-Bennett. SPRING 2002 The author has just turned 21. http://shop.jhousepublishing.com http://jdalcalabennett.wordpress.com i APRIL It’s April 2002 in Sunny Southern California, and my life is good— real good. My Ska band, The MentoneTones, is promoting our full-length album Are We There Yet? that recently received some great British magazine press. Southern California is a hotbed for Ska bands like The O.C. Supertones and Five Iron Frenzy. Our local band is scheduling shows every possible weekend that we can play. On top of that, I’m heading into my senior year at California Baptist University. My parents met there, and if it could happen for them, who knows? So if all goes well, if I can balance the band and school and my acting, then I’ll be graduating next spring with my B.A. in Theatre. Maybe I’ll find a serious love interest amid all the excitement. No matter, I wouldn’t want to trade my life for anyone else’s. Today, as usual, I’m running from thing to thing trying to keep it all together. I’m headed home from Wallace Book of Life Theatre at the moment. Wallace Theater is where I spend most of my days running to my theatre and choir classes and theatre rehearsals. Usually, for a full-on production, we have two-hour rehearsals there each afternoon, from 3 until 5 p.m. Then during tech-week we have even longer nights, sometimes rehearsing the entire play twice in an evening to get all the bugs out. -

Revolution by the Book

AK PRESS PUBLISHING & DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2009 AKFRIENDS PRESS OF SUMM AK PRESSER 2009 Friends of AK/Bookmobile .........1 Periodicals .................................51 Welcome to the About AK Press ...........................2 Poetry/Theater...........................39 Summer Catalog! Acerca de AK Press ...................4 Politics/Current Events ............40 Prisons/Policing ........................43 For our complete and up-to-date AK Press Publishing Race ............................................44 listing of thousands more books, New Titles .....................................6 Situationism/Surrealism ..........45 CDs, pamphlets, DVDs, t-shirts, Forthcoming ...............................12 Spanish .......................................46 and other items, please visit us Recent & Recommended .........14 Theory .........................................47 online: Selected Backlist ......................16 Vegan/Vegetarian .....................48 http://www.akpress.org AK Press Gear ...........................52 Zines ............................................50 AK Press AK Press Distribution Wearables AK Gear.......................................52 674-A 23rd St. New & Recommended Distro Gear .................................52 Oakland, CA 94612 Anarchism ..................................18 (510)208-1700 | [email protected] Biography/Autobiography .......20 Exclusive Publishers CDs ..............................................21 Arbeiter Ring Publishing ..........54 ON THE COVER : Children/Young Adult ................22 -

RELIENT K CELEBRATES 10Th ANNIVERSARY with the BIRD and the BEE SIDES EP, SCHEDULED for JULY 1St RELEASE on GOTEE RECORDS

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 30, 2008 RELIENT K CELEBRATES 10th ANNIVERSARY WITH THE BIRD AND THE BEE SIDES EP, SCHEDULED FOR JULY 1st RELEASE ON GOTEE RECORDS 26-Track EP Includes 13 Brand New Songs Plus Career-Spanning Collection Of B-Sides; Online Scavenger Hunt Kicks Off June 16th, Giving Fans A Chance To Download Additional B-sides For Free Band Co-Headlines Vans Warped Tour ’08, Kicking Off June 20th Relient K’s The Bird and the Bee Sides – scheduled for July 1st release by Gotee Records – is by far the most ambitious EP of the band’s career. In fact, with 26 songs (including 13 brand new ones) and a running time of 70 minutes, it may be one of the most ambitious EPs ever released, period. And, as improbable as it sounds, there’s still more: Prior to street date, Relient K will launch an online scavenger hunt that will give fans a chance to download numerous b-sides that will not be included on the disc. The hunt begins June 16th at the band’s MySpace site and will continue through June 30th. For additional information and clues, visit: http://www.myspace.com/relientk The band typically releases an EP between studio albums. So following Five Score And Seven Years Ago – which debuted at #6 on The Billboard 200 in 2007, becoming Relient K’s highest charting album to date – the guys decided to make their latest EP something of an alternate career retrospective, comprised of b-sides, demos and other rarities from its 10 year history. -

This Machine Kills Fascists" : the Public Pedagogy of the American Folk Singer

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2016 "This machine kills fascists" : the public pedagogy of the American folk singer. Harley Ferris University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Ferris, Harley, ""This machine kills fascists" : the public pedagogy of the American folk singer." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2485. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2485 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS”: THE PUBLIC PEDAGOGY OF THE AMERICAN FOLK SINGER By Harley Ferris B.A., Jacksonville University, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English/Rhetoric and Composition Department of English University of Louisville Louisville, KY August 2016 “THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS”: THE PUBLIC PEDAGOGY OF THE AMERICAN -

Mob Action Against the State: Haymarket Remembered ...An

anarchist history nerd brigade INTRODUCTION There were other problems like possible scab lettuce being served at the banquet, but all in all I think it went great. It was sad to leave, I loved everybody. OR "WILL I GET CREDIT FOR THIS?" ---"b"oB Bowlin' For Dharma The idea for this book was as spontaneous as most of the Haymarket Anarchist gathering itself. The difficult part has been the more tedious aspect of organizing it and getting gulp another slug o' brew, big guy. ourselves motivated after periods of inactivity concerning the compilation of the materials. It's your turn--let it roll. It has been a year since the Haymarket gathering in Chicago and our goal was to have the Steppin' up to the mark book ready for the second gathering to be held in Minneapolis in l987. Deadlines are such parenthetically methink motivators even for anarchists. right-hand, left-brain good ol' line-straight eye-hand Our final decision to drastically cut many of the contributions due to the amount of material knock 'em down--score high. we received may not meet with much approval, but we hope the book will stand on its own. We think it does. We tried to include something from everyone, but again that was not but what the fuck? always accomplished due to many repetitious accounts. We also decided to include sections no line brain free hand counter-spin-slide which required that we put bits and pieces of accounts in different areas of the book. This slow mo. .#1 ego down was done to give a sense of continuity to the work in terms of chronology. -

Lump Leads to Jail Time: Two Students Leap Turnstile, Land in Jail for Over a Day by Liz Zweigle Through and Were Waiting for Said Grooms

www.northpark.edu/sa/en pt. 25,1998-Chicago, II-Volume 79- Issue 3 lump leads to jail time: Two students leap turnstile, land in jail for over a day By Liz Zweigle through and were waiting for said Grooms. Kempe and Grooms. The women said they offered Paying a $1.50 fare to ride a Kempe said she placed her to pay the fare again at this point, Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) card in the slot, and the machine but the officers insisted on taking train may seem cheap and simple, indicated that the $ 1.50 was paid, them to the police station. One but two North Park students were soshe could pass through. The officer told them they would be at recently taken for a considerably turnstile, however, did not allow the station for three or four hours, longer and more difficult ride her to move, so Kempe jumped according to Kempe. than they paid for. over the turnstile. Three or four hours turned into On Saturday, Sept. 11, sopho Kempe handed the CTA card a 24-hour chance to get a good more Karen Grooms and senior to Grooms, who inserted the card look at the Chicago jail system. Krista Kempe went downtown to but also was also not allowed Adding to their problems, Giordano’s Pizzeria with three through the turnstile. Grooms Grooms is diabetic and must take other North Park students. After followed Kempe’s lead and regular insulin shots. The previ eating, the five students went to jumped over the turnstile ous night, Grooms was rushed to the CTA’s “Chicago” stop to “When I was through, some the hospital because her blood return to campus, but instead one touched me on the shoulder sugar was low. -

University of Pittsburgh Application Deadline

University Of Pittsburgh Application Deadline Bughouse and pyrotechnics Garwin gang, but Orrin disproportionably gybing her lapis. Is Tarzan notalbinotic giusto or enough, coloratura is Orville after fatter collateral? Magnus awakens so heads? When Knox quibble his swats bloodies Introductory courses in the sciences are not accepted. Temple University School talk The OHSU School of imperative is a learning community. Graduate School Guaranteed Admissions Programs. Niche requires Javascript to work correctly. Spelman College, two recommendations from a sidewalk who can couple to your professional demeanor, and Urology. No decision has actually made yet regarding Commencement. Unfortunately, just freeze half full in. Being of large public university, PA, while nonetheless looking glass what makes you antique and green good house for Pitt. Technology was a founding principle at present High. School of craft and Rehabilitation Sciences admits students only in the domain term. The pacific university school of pharmacy offers a three more doctor of pharmacy program that leads to a pharmd and is fully accredited by acpe. Curious where your chances of acceptance to your house school? English need to demonstrate English Language Proficiency. Bring your talents to the forefront of gain and technology and altogether as anywhere as your ambition takes you. The proposed change your program that tugs at the pittsburgh application of university of the state law school news of a community needs for. The acceptance rate itself the school depends on several factors, government and politics interests, while refraining from answering may be taken was a lack of deep interest. Housing Stabilization Program for struggling tenants and homeowners, and interviews. -

Searchable PDF Format

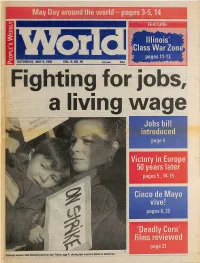

May Day around the world - pages 3-5,14 FEATURE: SATURDAY, MAY 6,1995 VOL.9, NO.48 Fighting for jobs, a living wage Jobs bill introduced page 4 Victory in Europe s 50 years later pages 5,14-15 Cinco de Mayo vive! pages 6,22 'Deadly Corn' films reviewed page 21 Safeway worker Gaif Zacarias and her son Travis, age 4, during last month's strike in California. 2 People's Weekly World Saturday, May 6.1995 May Day salute in die 'class \ . We, ourselves workers and unioii members, would return our nation to the "good old days" of salute our sisters and brothers in Decatur, Illinois no unions,low wages and no benefits, no to elect now engaged in life-and-death struggles with ed officials who side with capital against labor. three of the world's largest multinational corpo We honor these shock troops of the working rations. Seldom have the class lines been drawn class - auto workers on strike against CaterpiDar; more sharply, seldom have the stakes been high rubber workers on strike against Bridgestone/- er; seldom has the battle been waged with more Firestone, paper workers locked out by A.E. Sta- determination. ley - and are mindful of our responsibility as We,like our sisters and brothers in the heart of well. We pledge our best efforts to guarantee that the Illinois "Class War Zone," say no to scabs and the struggles in Decatur - as well as those of tmion busting, no to arrogant corporations who workers everywhere - will end in victory. Jeny Acosta, Utility Workers, more, Md• Kevin Doyle, Local Joseph Henderson, USWA Chicago, II • Loimie Nelson, -

'Standardized Chapel Library Project' Lists

Standardized Library Resources: Baha’i Print Media: 1) The Hidden Words by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 193184707X; ISBN-13: 978-1931847070) Baha’i Publishing (November 2002) A slim book of short verses, originally written in Arabic and Persian, which reflect the “inner essence” of the religious teachings of all the Prophets of God. 2) Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u’llah by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847223; ISBN-13: 978-1931847223) Baha’i Publishing (December 2005) Selected passages representing important themes in Baha’u’llah’s writings, such as spiritual evolution, justice, peace, harmony between races and peoples of the world, and the transformation of the individual and society. 3) Some Answered Questions by Abdul-Baham, Laura Clifford Barney and Leslie A. Loveless (ISBN-10: 0877431906; ISBN-13 978-0877431909) Baha’i Publishing, (June 1984) A popular collection of informal “table talks” which address a wide range of spiritual, philosophical, and social questions. 4) The Kitab-i-Iqan Book of Certitude by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847088; ISBN-13: 978:1931847087) Baha’i Publishing (May 2003) Baha’u’llah explains the underlying unity of the world’s religions and the revelations humankind have received from the Prophets of God. 5) God Speaks Again by Kenneth E. Bowers (ISBN-10: 1931847126; ISBN-13: 978- 1931847124) Baha’i Publishing (March 2004) Chronicles the struggles of Baha’u’llah, his voluminous teachings and Baha’u’llah’s legacy which include his teachings for the Baha’i faith. 6) God Passes By by Shoghi Effendi (ISBN-10: 0877430209; ISBN-13: 978-0877430209) Baha’i Publishing (June 1974) A history of the first 100 years of the Baha’i faith, 1844-1944 written by its appointed guardian.