Reinventing National Identity in a World of Globalized Soccer: the Case of the Uruguayan National Team

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda Semanal FILBA

Ya no (Dir. María Angélica Gil). 20 h proyecto En el camino de los perros AGENDA Cortometraje de ficción inspirado en PRESENTACIÓN: Libro El corazón y a la movida de los slam de poesía el clásico poema de Idea Vilariño. disuelto de la selva, de Teresa Amy. oral, proponen la generación de ABRIL, 26 AL 29 Idea (Dir. Mario Jacob). Documental Editorial Lisboa. climas sonoros hipnóticos y una testimonial sobre Idea Vilariño, Uno de los secretos mejor propuesta escénica andrógina. realizado en base a entrevistas guardados de la poesía uruguaya. realizadas con la poeta por los Reconocida por Marosa Di Giorgio, POÉTICAS investigadores Rosario Peyrou y Roberto Appratto y Alfredo Fressia ACTIVIDADES ESPECIALES Pablo Rocca. como una voz polifónica y personal, MONTEVIDEANAS fue también traductora de poetas EN SALA DOMINGO FAUSTINO 18 h checos y eslavos. Editorial Lisboa SARMIENTO ZURCIDORA: Recital de la presenta en el stand Montevideo de JUEVES 26 cantautora Papina de Palma. la FIL 2018 el poemario póstumo de 17 a 18:30 h APERTURA Integrante del grupo Coralinas, Teresa Amy (1950-2017), El corazón CONFERENCIA: Marosa di Giorgio publicó en 2016 su primer álbum disuelto de la selva. Participan Isabel e Idea Vilariño: Dos poéticas en solista Instantes decisivos (Bizarro de la Fuente y Melba Guariglia. pugna. 18 h Records). El disco fue grabado entre Revisión sobre ambas poetas iNAUGURACIÓN DE LA 44ª FERIA Montevideo y Buenos Aires con 21 h montevideanas, a través de material INTERNACIONAL DEL producción artística de Juanito LECTURA: Cinco poetas. Cinco fotográfico de archivo. LIBRO DE BUENOS AIRES El Cantor. escrituras diferentes. -

2016 Panini Flawless Soccer Cards Checklist

Card Set Number Player Base 1 Keisuke Honda Base 2 Riccardo Montolivo Base 3 Antoine Griezmann Base 4 Fernando Torres Base 5 Koke Base 6 Ilkay Gundogan Base 7 Marco Reus Base 8 Mats Hummels Base 9 Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang Base 10 Shinji Kagawa Base 11 Andres Iniesta Base 12 Dani Alves Base 13 Lionel Messi Base 14 Luis Suarez Base 15 Neymar Jr. Base 16 Arjen Robben Base 17 Arturo Vidal Base 18 Franck Ribery Base 19 Manuel Neuer Base 20 Thomas Muller Base 21 Fernando Muslera Base 22 Wesley Sneijder Base 23 David Luiz Base 24 Edinson Cavani Base 25 Marco Verratti Base 26 Thiago Silva Base 27 Zlatan Ibrahimovic Base 28 Cristiano Ronaldo Base 29 Gareth Bale Base 30 Keylor Navas Base 31 James Rodriguez Base 32 Raphael Varane Base 33 Karim Benzema Base 34 Axel Witsel Base 35 Ezequiel Garay Base 36 Hulk Base 37 Angel Di Maria Base 38 Gonzalo Higuain Base 39 Javier Mascherano Base 40 Lionel Messi Base 41 Pablo Zabaleta Base 42 Sergio Aguero Base 43 Eden Hazard Base 44 Jan Vertonghen Base 45 Marouane Fellaini Base 46 Romelu Lukaku Base 47 Thibaut Courtois Base 48 Vincent Kompany Base 49 Edin Dzeko Base 50 Dani Alves Base 51 David Luiz Base 52 Kaka Base 53 Neymar Jr. Base 54 Thiago Silva Base 55 Alexis Sanchez Base 56 Arturo Vidal Base 57 Claudio Bravo Base 58 James Rodriguez Base 59 Radamel Falcao Base 60 Ivan Rakitic Base 61 Luka Modric Base 62 Mario Mandzukic Base 63 Gary Cahill Base 64 Joe Hart Base 65 Raheem Sterling Base 66 Wayne Rooney Base 67 Hugo Lloris Base 68 Morgan Schneiderlin Base 69 Olivier Giroud Base 70 Patrice Evra Base 71 Paul -

2015 Select Soccer Team HITS Checklist;

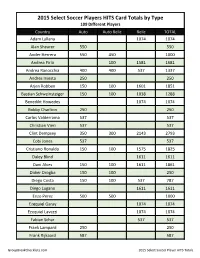

2015 Select Soccer Players HITS Card Totals by Type 109 Different Players Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Adam Lallana 1074 1074 Alan Shearer 550 550 Ander Herrera 550 450 1000 Andrea Pirlo 100 1581 1681 Andrea Ranocchia 400 400 537 1337 Andres Iniesta 250 250 Arjen Robben 150 100 1601 1851 Bastian Schweinsteiger 150 100 1038 1288 Benedikt Howedes 1074 1074 Bobby Charlton 250 250 Carlos Valderrama 537 537 Christian Vieri 537 537 Clint Dempsey 350 300 2143 2793 Cobi Jones 537 537 Cristiano Ronaldo 150 100 1575 1825 Daley Blind 1611 1611 Dani Alves 150 100 1611 1861 Didier Drogba 150 100 250 Diego Costa 150 100 537 787 Diego Lugano 1611 1611 Enzo Perez 500 500 1000 Ezequiel Garay 1074 1074 Ezequiel Lavezzi 1074 1074 Fabian Schar 537 537 Frank Lampard 250 250 Frank Rijkaard 587 587 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2015 Select Soccer Player HITS Totals Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Franz Beckenbauer 250 250 Gerard Pique 150 100 1601 1851 Gervinho 525 475 1611 2611 Gianluigi Buffon 125 125 1521 1771 Guillermo Ochoa 335 125 1611 2071 Harry Kane 513 503 537 1553 Hector Herrera 537 537 Hugo Sanchez 539 539 Iker Casillas 1591 1591 Ivan Rakitic 450 450 1024 1924 Ivan Zamorano 537 537 James Rodriguez 125 125 1611 1861 Jan Vertonghen 200 150 1074 1424 Jasper Cillessen 1575 1575 Javier Mascherano 1074 1074 Joao Moutinho 1611 1611 Joe Hart 175 175 1561 1911 John Terry 587 100 687 Jordan Henderson 1074 1074 Jorge Campos 587 587 Jozy Altidore 275 225 1611 2111 Juan Mata 425 375 800 Jurgen Klinsmann 250 250 Karim Benzema 537 537 Kevin Mirallas 525 475 -

Football Agents in the Biggest Five European Football Markets an Empirical Research Report

FOOTBALL AGENTS IN THE BIGGEST FIVE EUROPEAN FOOTBALL MARKETS AN EMPIRICAL RESEARCH REPORT FEBRUARY 2012 Raffaele Poli, CIES Football Observatory, University of Neuchâtel Giambattista Rossi, João Havelange Scholarship, Birkbeck University (London) With the collaboration of Roger Besson, CIES Football Observatory, University of Neuchâtel Football agent portrayed by the Ivorian woodcarver Bienwélé Coulibaly Executive summary While intermediaries acting in the transfers of footballers have existed since almost the birth of the professional game, the profession of agent was not officially recognised until 1991 when FIFA established the first official licensing system. In November 2011, there were 6,082 licensed agents worldwide: 41% of them were domiciled within countries hosting the big five European leagues: England, Spain, Germany, Italy and France. This research project firstly investigates shares in the representation market of players in the five major European championships. By presenting the results of a survey questionnaire, it analyses the socio-demographic profile of licensed football agents in the above mentioned countries, the business structure of their activity, the different kinds of services provided, and the way in which they are performed from a relational point of view (network approach). The analysis of shares highlights that the big five league players’ representation market is highly concentrated: half of the footballers are managed by 83 football agents or agencies. Our study reveals the existence of closed relational networks that clearly favors the concentration of players under the control of few agents. Footballers are not equally distributed between intermediaries. Conversely, dominant actors exist alongside dominated agents. One fifth of the agents having answered to our questionnaire manage the career of half of the players represented on the whole. -

Hyperreality in a Football Live on Television

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 108 Social Sciences, Humanities and Economics Conference (SoSHEC 2017) Hyperreality in a Football Live on Television Rojil Nugroho Bayu Aji Eko Satriya Hermawan History Education Department History Education Department Universitas Negeri Surabaya Universitas Negeri Surabaya Surabaya, Indonesia Surabaya, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] Riyadi History Education Department Universitas Negeri Surabaya Surabaya, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract– Today spotlight of direct camera in a football elide into more comprehensive reflections on a multiplicity of match is inevitable. Hundreds of cameras are always prepared in emotions. Even in the midst of a cheering crowd, the stadium every football match in order to catch every second of the events, will always be a place for quiet contemplation for everyone [3]. both inside and outside the stadium. As the result, we can access Football was also a competitive sport that was contested. It football matches anywhere from our television or our cellphone. started with the qualification in each regional federation. It This article was aimed to show how football matches live on became a prestigious and favorite sport that competed in sport television and cellphone is not neutral. There were many values international championship. Nowadays, football and television appeared because it was not meant to be real and exactly the cannot be separated each other. Television is a tool to form of same as the football matches we watch with our own eyes. This mass consumption including in football live show. This is an was a hyperreality in football matches live on television that we important thing to interpret that there is a new framing through enjoy seeing it over the years. -

Neymarlograungolazo

18 FUTBOL MUNDO DEPORTIVO Domingo 1dejunio de 2014 Thiago Silva, baja el martes, dijo que el barcelonista “será el crack del Mundial” Van Gaal anunció la lista final del rival de España Holanda derrota aGhana Neymar logra un golazo con otro gol de Van Persie Imma Mentruit/Jordi Archs Holanda, 1 Cillessen; Janmaat, Vlaar, De Vrij, Martins Indi, Blind; n Neymar fue ayer uno de los Nigel de Jong, Sneijder (Lens, 82'), De Guzman; Van Persie grandes protagonistas en el entre- (Depay, 74') yRobben Ghana, 0 namiento de Brasil, en el que el Kwarasey; Inkoom, Sumaila, Akaminko (Mensah, 93'), joven astro barcelonista logró un Schlupp (Afful, 69'); Adomah, Essien (Afriyie Acquah, 46'); Atsu (Kevin-Prince Boateng, 46'), Rabiu (André Ayew, 64'), golazo. Recibió el Asamoah; Jordan Ayew (Waris, 56) balón aladere- Gol: 1-0, VanPersie (5') Espectadores: 46.000 en el De Kuip de Rotterdam cha del área y, ca- Árbitro: Carlos Sistra (Portugal).Amarilla aJordan Ayew si sin ángulo, bur- (32') ló aladefensa y conectó un leve ROTTERDAM- Robin van Persie ratifi- toque con el que có que es el goleador de Holanda. batió al meta Jef- 'Pichichi' históricodelos 'oranje', ferson,alque des- dio ayer el triunfo ante Ghana colocó. Thiago (1-0)con su 43º tanto internacio- Silva, capitán de nal en 84 partidos. Hace una se- Brasil, dijo sobre mana ya vio puerta ante Ecuador 'Pîchichi' Van Persie Lleva 43 goles FOTO: EFE el azulgrana: “Neymar será el en Amsterdam(1-1) en el primer crack del Mundial. Nuestro punto ensayo del rival ante el que debu- LA LISTA DE 23 DE VAN GAAL fuerte siempre fue la calidad colec- tará España en el Mundial. -

Dilatan Regreso Del “Bombero”

10597925 06/07/2005 11:33 p.m. Page 3 DEPORTES | JUEVES 7 DE JULIO DE 2005 | EL SIGLO DE DURANGO | 3D ANHELO | ATLÉTICO PARANAENSE BUSCA SU PRIMER TÍTULO CONTINENTAL Salva autogol al Sao Paulo en Libertadores Imagen del infortunado boxeador Martín “Bombero” Sánchez. Equipo rojinegro jugó como local a más Dilatan regreso de 500 kilómetros de su estadio del “Bombero” AGENCIAS AGENCIA REFORMA PORTO ALEGRE, BRASIL.- Sao Paulo, MÉXICO, DF.- Los trámites burocráticos están re- con la ayuda de un autogol, consi- trasando el traslado a la Ciudad de México del guió ayer un empate a domicilio 1- cuerpo del mexicano Martín “Bombero” Sán- 1 con el Atlético Paranaense, en el chez, fallecido el pasado sábado en Las Vegas, encuentro de ida de la inédita final Nevada, aseguró la familia del púgil. entre dos brasileños por la Copa Los familiares ya no pueden más. La ausen- Libertadores. cia de una firma por parte de la Secretaría de Sa- El equipo rojinegro del Atléti- lud de Estados Unidos, y la autorización por par- co Paranaense abrió el marcador a te del Consulado mexicano en el estado de Neva- los 14 minutos mediante un cabe- da, tienen detenida la llegada de Sánchez al Dis- zazo de Aloisio, pero Durval la trito Federal. metió en su propia puerta a los 53 “Lo que quisiéramos resolver en estos mo- para establecer el resultado defi- mentos, es que ya traigan a mi hermano, porque nitivo. El duelo de vuelta se juga- ya estamos desesperados, la espera es muy du- rá el jueves de la semana próxima ra. -

Aronaldosólolefaltóelgol

28 FÚTBOL INTERNACIONAL MUNDO DEPORTIVO Jueves 9dejunio de 2011 AREl 'Fenómeno'onaldose despidió del fútbol jugandosólo15 minutos conleBrasil perofaltóel meta rumanoelno se sumógolalafiesta COPA AMÉRICA Brasil, 1 Víctor; Maicon, Lúcio (Luisao, 70'), David Luiz, André Santos; Sandro (Lucas Leiva, 59'), Elías, Jadson; Fred (Ronaldo, 30') (Nilmar, 46'), Neymar (Thiago Neves, 76') yRobinho Sergio Batista Replica aTevez FOTO: PEP MORATA (Lucas Moura, 65') Rumanía, 0 Tatarusanu (Pantilimon, 65'); Rapa, Papp, Gardos, Latovlevici; Muresan (Alexa, 80'), Torje, Bourceanu (Giurgiu, Batista: “No ganar el 66'), Sanmartean (Alexe, 53'); Surdu (Tanase, 45') yMarica (Zicu, 72') título no sería fracasar” Gol: 1-0, Fred (21') Esp.: 30.000 en el Pacaembú de SaoPaulo Árbitro: Sergio Pezzotta (Argentina). Amarilla aMuresan (69') BUENOS AIRES- “Estamos obligados a ganar la Copa América porque tendrá Hans Henningsen Río lugar aquí, pero si no, no será un fracaso”. Así se expresa Sergio Batista, n Cuatro meses después de anun- seleccionador albiceleste, de cara al ciar su retirada,enlamadrugada torneo que, apartir del 1dejulio, su de ayer Ronaldo se despidió del Ronaldo jugó los últimos 15 minutos de la primera parte. equipo disputará como anfitrión. “Las fútbol jugando los últimos 15 mi- Dio la vuelta al campo envuelto en la bandera de Brasil y expectativas son muchísimas, y nutos de la primera parte del amis- se dirigió al público. Su hijo Alex le grabó Ⴇ FOTOS: AP Argentina, como en todo, está toso que la selección brasileña ga- obligada al éxito. Lo que sabemos es nó aRumanía (1-0) en el estadio que la selección necesita un Mundial”. Pacaembú de Sao Paulo. -

ECA Esearch July 2011

1-24 July ECA esearch July 2011 Table of Contents Foreword …………………………….……………………………………………………………………… p.3 Club origin of the player…...……………………………………………………………………… p.3 European club’s analysis by Country………………………………………………… p.4 Most represented National championships in Europe……………………… p.6 Most represented European clubs ……………………………………………….………… p.7 Disclaimer This research is based on the national football squads for the 2011 CONMEBOL Campeonato Sudamericano Copa América Cup published on the 30th of June. The European Club Association has endeavoured to keep the information up to date, but it makes no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, with respect to this information. The aim of this research is purely informative. European Club Association – July 2011 2 The CONMEBOL Campeonato Sudamericano Copa América, better known as the Copa América is the main international football competition in South America. It is played every four years and involves all 10 National Associations belonging to the CONMEBOL plus 2 guest Associations using U23/Olympic squad. This edition Mexico and Costa Rica from CONCACAF were invited. Copa América Argentina 2011 finals are held in Argentina in 8 venues (played in Buenos Aires, Mendoza, Córdoba, Salta, Jujuy, San Juan, La Plata and Santa Fe) between the 1st and the 24th of July. It is the 43rd time the tournament takes place. As South American champions, the National team will earn the right to compete for the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup in Brazil. 7 NA’s have won the trophy, with Argentina and Uruguay both all having won it 14 times. Brazil follows with 8 titles. -

Uruguay Franci

LA PRENSA GRÁFICA VIERNES 11 DE JUNIO DE 2010 LA TRIBUNA 8 www.laprensagrafica.com SUDÁFRICA PLANTILLA EL TÉCNICO NOMBRE POSICIÓN GRUPO A 1 Itumeleng Khune Arquero CARLOS PARREIRA 2 Moeneeb Josephs Arquero FECHA DE NACIMIENTO: 27 DE ABRIL DE 1947 3 Shu-Aib Walters Arquero LUGAR DE NACIMIENTO: 4 Matthew Booth Defensa RÍO DE JANEIRO, BRASIL 5 Siboniso Gaxa Defensa TRAYECTORIA: 6 Bongani Khumalo Defensa AL DIRIGIR A SUDÁFRICA EN EL MUNDIAL DE 2010, PARREIRA 7 Tsepo Masilela Defensa IGUALARÁ AL SERBIO BORA 8 Aaron Mokoena Defensa MILUTINOVIC COMO LOS 9 Anele Ngcongca Defensa AQUÍ DOS ENTRENADORES CON MÁS 10 Siyabonga Sangweni Defensa PARTICIPACIONES EN MUNDIALES, 11 Lucas Thwala Defensa CON SEIS EDICIONES CADA UNO. 12 Lance Davids Mediocampista 13 Kagisho Dikgacoi Mediocampista LA LISTA DEL ANFITRIÓN 14 Thanduyise Khuboni Mediocampista Sudáfrica espera tener su mejor participación en 15 Reneilwe Letsholonyane Mediocampista TENDRÁN una Copa del Mundo amparada en sus jugadores 16 Teko Modise Mediocampista con experiencia europea. Pese a que Carlos Parreira 17 Surprise Moriri Mediocampista dejó fuera de la lista a Benny McCarthy por sus 18 Steven Pienaar Mediocampista 19 Siphiwe Tshabalala Mediocampista problemas físicos, esta tiene otros jugadores con 20 Macbeth Sibaya Mediocampista experiencia europea, donde el principal referente 21 Katlego Mphela Delantero ahora es Steven Pienaar, quien jugó para el Ajax 22 Siyabonga Nomvete Delantero FRACASO 23 Bernaard Parker Delantero de Holanda, y hoy participa en la Premier League. Dos ex campeones del mundo, Uruguay y ASOC. DE FÚTBOL DE SUDÁFRICA PALMARÉS EN LA COPA MUNDIAL PAÍS: SUDÁFRICA GANADOR: 0 CONTINENTE: ÁFRICA SEGUNDO: 0 Francia, contra el anfitrión del torneo, ABREVIATURA FIFA: RSA PARTICIPACIONES EN LA COPA AÑO DE FUNDACIÓN: 1932 MUNDIAL DE LA FIFA: AFILIADO DESDE: 1932 2 (1998, 2002) Sudáfrica, y como invitado de cierre una de las CONFEDERACIÓN: CAF NOMBRE: STEVEN PIENAAR HISTORIAL: Pienaar será el potencias de CONCACAF, México. -

2016 Panini Flawless Card Totals by PLAYER (173 Players with Cards/114 Players with Auto/Relics)

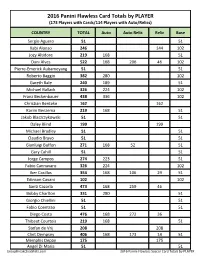

2016 Panini Flawless Card Totals by PLAYER (173 Players with Cards/114 Players with Auto/Relics) COUNTRY TOTAL Auto Auto Relic Relic Base Sergio Aguero 51 51 Xabi Alonso 246 144 102 Jozy Altidore 219 168 51 Dani Alves 522 168 206 46 102 Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang 51 51 Roberto Baggio 382 280 102 Gareth Bale 240 189 51 Michael Ballack 326 224 102 Franz Beckenbauer 438 336 102 Christian Benteke 162 162 Karim Benzema 219 168 51 Jakub Blaszczykowski 51 51 Daley Blind 199 199 Michael Bradley 51 51 Claudio Bravo 51 51 Gianluigi Buffon 271 168 52 51 Gary Cahill 51 51 Jorge Campos 274 223 51 Fabio Cannavaro 326 224 102 Iker Casillas 354 168 106 29 51 Edinson Cavani 102 102 Santi Cazorla 473 168 259 46 Bobby Charlton 331 280 51 Giorgio Chiellini 51 51 Fabio Coentrao 51 51 Diego Costa 476 168 272 36 Thibaut Courtois 219 168 51 Stefan de Vrij 208 208 Clint Dempsey 406 168 173 14 51 Memphis Depay 175 175 Angel Di Maria 51 51 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2016 Panini Flawless Soccer Card Totals by PLAYER COUNTRY TOTAL Auto Auto Relic Relic Base Antonio Di Natale 112 112 Didier Drogba 275 224 51 Edin Dzeko 51 51 Samuel Eto'o 99 99 Patrice Evra 51 51 Cesc Fabregas 51 51 Radamel Falcao 51 51 Marouane Fellaini 219 168 51 Ezequiel Garay 246 195 51 Steven Gerrard 519 168 264 36 51 Gervinho 170 170 Olivier Giroud 51 51 Diego Godin 51 51 Mario Gotze 419 224 144 51 Antoine Griezmann 51 51 Ruud Gullit 437 335 102 Ilkay Gundogan 51 51 Joe Hart 474 168 188 67 51 Eden Hazard 51 51 Jordan Henderson 67 67 Xavi Hernandez 584 224 222 36 102 Ander Herrera 139 139 Hector -

Enciclopédia 2020 Volume Xlv Recordes Individuais Dos

ENCICLOPÉDIA 2020 45VOLUME XLV RECORDES INDIVIDUAIS DOS TRICOLORES RECORDES DE JOGADORES PELO SÃO PAULO MAIS TÍTULOS PELO CLUBE Número de títulos Rogério Ceni, 18 Títulos com presença em campo Rogério Ceni e Ronaldão, 12 MAIS PARTIDAS PELO CLUBE Geral Rogério Ceni, 1237 Competitivas Rogério Ceni, 1197 Campanhas de títulos Rogério Ceni, 193 Decisões de título Müller e Zetti, 11 Finais de campeonato Rogério Ceni, 30 Brasileiro Rogério Ceni, 575 Brasileiro de pontos corridos Rogério Ceni, 428 Copa do Brasil Rogério Ceni, 67 Paulista Waldir Peres, 343 Libertadores Rogério Ceni, 90 Competição Internacional Rogério Ceni, 186 Jogos Internacionais Rogério Ceni, 152 Exterior Rogério Ceni, 82 Território nacional Rogério Ceni, 1155 Mata-mata oficial Rogério Ceni, 245 Clássicos Nacionais Rogério Ceni, 481 Clássicos Estaduais Rogério Ceni, 189 RECORDES DE JOGADORES PELO SÃO PAULO Trio de Ferro Rogério Ceni, 125 Principais Times do Eixo Rio-SP Rogério Ceni, 343 Com + de 50 mil torcedores Rogério Ceni, 66 Com + de 70 mil torcedores Darío Pereyra, 30 Com + de 100 mil torcedores Darío Pereyra e Zé Sérgio, 7 Mandante Rogério Ceni, 617 Visitante ou neutro Rogério Ceni, 620 Titular Rogério Ceni, 1234 Somente como titular Ruy Campos, 273 Substituto Souza (Willamis), 77 Até 17 anos de idade Denilson (1995), 43 Até 20 anos de idade Denilson (1995), 190 Com 30 anos ou mais Rogério Ceni, 799 Com 35 anos ou mais Rogério Ceni, 458 Com 40 anos ou mais Rogério Ceni, 186 Século XX Waldir Peres, 617 Século XXI Rogério Ceni, 906 Anos 1930-1940 Armandinho, 149 Anos 1941-1950