The Emergence of the Scottish Broadside Ballad in the Late

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 AMTA Conference Promises to Bring You Many Opportunities to Network, Learn, Think, Play, and Re-Energize

Celebrating years Celebrating years ofof musicmusic therapytherapy the past... t of k ou oc R re utu e F th to in with ll nd o Music a R Therapy official conference program RENAISSANCE CLEVELAND HOTEL Program Sponsored by: CLEVELAND, OHIO welcome ...from the Conference Chair elcome and thank you for joining us in Cleveland to celebrate sixty years of music Wtherapy. And there is much to celebrate! Review the past with the historical posters, informative presentations and the inaugural Bitcon Lecture combining history, music and audience involvement. Enjoy the present by taking advantage of networking, making music with friends, new and old, and exploring some of the many exciting opportunities available just a short distance from the hotel. The conference offers an extensive array of opportunities for learning with institutes, continuing education, and concurrent sessions. Take advantage of the exceptional opportunities to prepare yourself for the future as you attend innovative sessions, and talk with colleagues at the clinical practice forum or the poster research session. After being energized and inspired the challenge is to leave Cleveland with both plans and dreams for what we can accomplish individually and together for music therapy as Amy Furman, MM, MT-BC; we roll into the next sixty years. AMTA Vice President and Conference Chair ...from the AMTA President n behalf of the AMTA Board of Directors, as well as local friends, family and colleagues, Oit is my distinct privilege and pleasure to welcome you to Cleveland to “rock out of the past and roll into the future with music therapy”! In my opinion, there is no better time or place to celebrate 60 years of the music therapy profession. -

The Songs of the Beggar's Opera

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1966 The onS gs of The Beggar's Opera Carolyn Anfinson Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Music at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Anfinson, Carolyn, "The onS gs of The Beggar's Opera" (1966). Masters Theses. 4265. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4265 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #3 To: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. Subject: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements. Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institutionts library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because Date Author THE SONGS OF THE BEGGAR'S OPERA (TITLE) BY Carolyn Anfinson THESIS SUBMIITTD IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.S. -

The Ballads of the Southern Mountains and the Escape from Old Europe

B AR B ARA C HING Happily Ever After in the Marketplace: The Ballads of the Southern Mountains and the Escape from Old Europe Between 1882 and 1898, Harvard English Professor Francis J. Child published The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, a five volume col- lection of ballad lyrics that he believed to pre-date the printing press. While ballad collections had been published before, the scope and pur- ported antiquity of Child’s project captured the public imagination; within a decade, folklorists and amateur folk song collectors excitedly reported finding versions of the ballads in the Appalachians. Many enthused about the ‘purity’ of their discoveries – due to the supposed isolation of the British immigrants from the corrupting influences of modernization. When Englishman Cecil Sharp visited the mountains in search of English ballads, he described the people he encountered as “just English peasant folk [who] do not seem to me to have taken on any distinctive American traits” (cited in Whisnant 116). Even during the mid-century folk revival, Kentuckian Jean Thomas, founder of the American Folk Song Festival, wrote in the liner notes to a 1960 Folk- ways album featuring highlights from the festival that at the close of the Elizabethan era, English, Scotch, and Scotch Irish wearied of the tyranny of their kings and spurred by undaunted courage and love of inde- pendence they braved the perils of uncharted seas to seek freedom in a new world. Some tarried in the colonies but the braver, bolder, more venturesome of spirit pressed deep into the Appalachians bringing with them – hope in their hearts, song on their lips – the song their Anglo-Saxon forbears had gathered from the wander- ing minstrels of Shakespeare’s time. -

Barbara Allen

120 Charles Seeger Versions and Variants of the Tunes of "Barbara Allen" As sung in traditional singing styles in the United States and recorded by field collectors who have deposited their discs and tapes in the Archive of American Folk Song in the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. AFS L 54 Edited by Charles Seeger PROBABLY IT IS safe to say that most English-speaking people in the United States know at least one ballad-tune or a derivative of one. If it is not "The Two Sisters, " it will surely be "When Johnny Comes Marching Home"; or if not "The Derby Ram, " then the old Broadway hit "Oh Didn't He Ramble." If. the title is given or the song sung to them, they will say "Oh yes, I know tllat tune." And probably that tune, more or less as they know it, is to them, the tune of the song. If they hear it sung differently, as may be the case, they are as likely to protest as to ignore or even not notice the difference. Afterward, in their recognition or singing of it, they are as likely to incor porate some of the differences as not to do so. If they do, they are as likely to be aware as to be entirely unconscious of having done ·so. But if they ad mit the difference yet grant that both singings are of "that" tune, they have taken the first step toward the study of the ballad-tune. They have acknow ledged that there are enough resemblances between the two to allow both to be called by the same name. -

May 26, 2016 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE MICHIGAN IRISH

May 26, 2016 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MICHIGAN IRISH MUSIC FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 2016 LINEUP 4-Day Festival Returns Sept. 15 - 18 The Michigan Irish Music Festival will kick off the 2016 festival with a Pub Preview Party again on Thursday night. The Pub Party will give patrons a preview of the weekend with food, beverage, and entertainment in the pub tent only. Entry is only $5 (cash only Thursday). Three bands will play Thursday. The full festival opens Friday with all five stages and the complete compliment of food, beverages (domestic beer, Irish whiskey, Irish cider and local craft beer), shopping and cultural/dance offerings. The music line-up is being finalized with over 20 bands on tap. Altan – The seeds of Altan lie in the music and spontaneity of sessions in kitchens and pubs in their hometown of Donegal, where their music was heard in an atmosphere of respect and intimacy. It is here that the band's heart still lies, whether they are performing on TV in Australia or jamming with Ricky Skaggs on the west coast of the United States. Andy Irvine – Andy Irvine is one of the great Irish singers, his voice one of a handful of truly great ones that gets to the very soul of Ireland. He has been hailed as "a tradition in himself." Musician, singer and songwriter, Andy has maintained his highly individual performing skills throughout his 45-year career. A festival favorite, Scythian, returns. Named after Ukrainian nomads, Scythian (sith-ee-yin) plays immigrant rock with thunderous energy, technical prowess, and storytelling songwriting, beckoning crowds into a barn-dance rock concert experience. -

The Chapbooks and Broadsides of James Chalmers III, Printer in Aberdeen: Some Re-Discoveries and Initial Observations on His Woodcuts

The Chapbooks and Broadsides of James Chalmers III, Printer in Aberdeen: Some Re-discoveries and Initial Observations on His Woodcuts IAIN BEAVAN BACKGROUND This essay consists of two related elements. First, an empirical discussion of recent evidence to emerge for chapbook and broadside production in Aberdeen. Second, a consideration of some features of the woodcuts used by James Chalmers III and other chapbook printers, which, in the present context, provide the central evidential theme of this investigation. Previous and contemporary scholars have argued that the north-east of Scotland has the richest ballad and popular song tradition in Britain, and that an analysis of Francis Child’s still unsurpassed and authoritative fi ve-volume compilation, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, shows that ‘one-third of Child’s Scottish texts and almost one-third of his A-texts [his base or ‘prime’ texts, from which variants may be identifi ed] come from Aberdeenshire’.1 Moreover, ‘of some 10,000 variants of Lowland Scottish songs recorded by the School of Scottish Studies [of Edinburgh University] … several thousand are from the Aberdeen area alone’.2 From the early eighteenth century, popular lowland Scottish song had found itself expressed in printed form, early appearances having been James Watson’s Choice Collection of Comic and Serious Scots Poems, 3 parts (Edinburgh, 1706–11), followed by the Edinburgh Miscellany (Edinburgh, 1720) and Allan Ramsay’s Tea-table Miscellany (Edinburgh, 1723).3 From the mid-eighteenth century also, Scottish chapbook texts appeared in ever increasing numbers, given over to different sub-genres, including histories, prophecies, humorous stories and collections of songs (often called garlands). -

Bonny Levine – 2015 All Nominees (Alpha Order), Answers to All Supporting Documentation Questions Table of Contents

Bonny LeVine – 2015 All Nominees (alpha order), Answers to all supporting documentation questions Table of Contents Bonny LeVine At A Glance…………………………………..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 Question 1: Detail your professional achievements…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….11 Question 2: How have these achievements advanced the principles of franchising as a viable business strategy, and its positive visibility?….27 Question 2a: How has your achievements helped women advance in the franchise industry? Please list specific activities and results that demonstrate your mentorship to women. Are there any mentorees that Committee members could contact regarding your impact?………….40 Question 3: List the leadership and/or committee/task force positions you have held at IFA……………………………………………………………………………56 Question 4: List other awards and honors bestowed upon you by the franchising community………………………………………………………………………….64 Question 5: Detail your history of community involvement………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..71 Question 6: Demonstrate how this has transcended commercial benefit and heightened the positive awareness of franchising…………………….87 Question 7: Provide details on any pertinent legal actions that concern franchise systems with which you have been affiliated………...............97 Question 8: Include any other information that you believe may be helpful to IFA in its consideration of you as an honoree………………………..101 Question 9: Are there legal, financial or other issues or situations that your selection as the recipient of an IFA award might raise which have the potential to attract negative publicity or attention for the association and/or the franchising industry? ……………………..112 2015 Bonny LeVine Award Documentation Nominee Name Lisa Almeida Cheryl Bachelder Jania Bailey Cathy Brown Title CEO CEO CEO Franchisee Owner & Area Director Company Name Freedom Boat Club Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen, FranNet Franchising, LLC Jersey Mike’s Subs Inc. -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B. -

The Routledge Dictionary of Literary Terms

The Routledge Dictionary of Literary Terms The Routledge Dictionary of Literary Terms is a twenty-first century update of Roger Fowler’s seminal Dictionary of Modern Critical Terms. Bringing together original entries written by such celebrated theorists as Terry Eagleton and Malcolm Bradbury with new definitions of current terms and controversies, this is the essential reference book for students of literature at all levels. This book includes: ● New definitions of contemporary critical issues such as ‘Cybercriticism’ and ‘Globalization’. ● An exhaustive range of entries, covering numerous aspects to such topics as genre, form, cultural theory and literary technique. ● Complete coverage of traditional and radical approaches to the study and production of literature. ● Thorough accounts of critical terminology and analyses of key academic debates. ● Full cross-referencing throughout and suggestions for further reading. Peter Childs is Professor of Modern English Literature at the University of Gloucestershire. His recent publications include Modernism (Routledge, 2000) and Contemporary Novelists: British Fiction Since 1970 (Palgrave, 2004). Roger Fowler (1939–99), the distinguished and long-serving Professor of English and Linguistics at the University of East Anglia, was the editor of the original Dictionary of Modern Critical Terms (Routledge, 1973, 1987). Also available from Routledge Poetry: The Basics Who’s Who in Contemporary Jeffrey Wainwright Women’s Writing 0–415–28764–2 Edited by Jane Eldridge Miller Shakespeare: The Basics 0–415–15981–4 -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

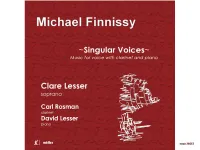

Michael Finnissy Singular Voices

Michael Finnissy Singular Voices 1 Lord Melbourne †* 15:40 2 Song 1 5:29 3 Song 16 4:57 4 Song 11 * 3:02 5 Song 14 3:11 6 Same as We 7:42 7 Song 15 7:15 Beuk o’ Newcassel Sangs †* 8 I. Up the Raw, maw bonny 2:21 9 II. I thought to marry a parson 1:39 10 III. Buy broom buzzems 3:18 11 IV. A’ the neet ower an’ ower 1:55 12 V. As me an’ me marra was gannin’ ta wark 1:54 13 VI. There’s Quayside fer sailors 1:19 14 VII. It’s O but aw ken weel 3:17 Total Duration including pauses 63:05 Clare Lesser soprano David Lesser piano † Carl Rosman clarinet * Michael Finnissy – A Singular Voice by David Lesser The works recorded here present an overview of Michael Finnissy’s continuing engagement with the expressive and lyrical possibilities of the solo soprano voice over a period of more than 20 years. It also explores the different ways that the composer has sought to ‘open-up’ the multiple tradition/s of both solo unaccompanied song, with its universal connotations of different folk and spiritual practices, and the ‘classical’ duo of voice and piano by introducing the clarinet, supremely Romantic in its lyrical shadowing of, and counterpoints to, the voice in Song 11 (1969-71) and Lord Melbourne (1980), and in an altogether more abrasive, even aggressive, way in the microtonal keenings and rantings of the rarely used and notoriously awkward C clarinet in Beuk O’ Newcassel Sangs (1988). -

Jimmy Grove and Barbara Ellen

Jimmy Grove and Barbara Ellen !1 JimmyThe New Christy Minstrel Grove interpretation of anda traditional balladBarbara Ellen D G A7 D In Scarlett Town long time ago, D G A7 D There was a fair maid dwellin’. D Bm F#m She was the fairest of the all, Intro G A7 D And her name was Barbara Ellen. D G A7 D All in the merry month of May, D G A7 D When the green buds were swellin’; D Bm F#m Then all the boys for miles around, G A7 D Came to call on Barbara Ellen. D G A7 D Don’t want you land, don’t want you gold, D G A7 D Nor all the sweet words you’re tellin’. D Bm F#m My heart belongs to to Jimmy Grove; G A7 D He’s comin’ home to Barbara Ellen. E A B7 E Don’t be a fool, don’t waste you life. E A B7 E You know that fortune has denied him. E C#m/G# G#m He has no land, he has no gold. A B7 E You’ll have to work and slave beside him. !2 E A B7 E I love him more than life can tell. E A B7 E And it’s true love that’s more compellin’ E C#m/G# G#m I’d rather have my Jimmy Grove, A B7 E Than all the world, cried Barbara Ellen. E A B7 E And when the war was almost done, E A B7 E They heard the steeple bells in heaven.