TWO-SPIRITS and the DECOLONIZATION of GENDER Bayu Kristianto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

True Colors Resource Guide

bois M gender-neutral M t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bois bois gender-neutral M gender-neutralLOVEM gender-neutral t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch Birls polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme Asexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious transsexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual bois M gender-neutral gender-neutral M t t F F ALLY Lesbian INTERSEX butch INTERSEXALLY Birls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer bisexual Asexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual bi-curious bi-curious transsexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bois bois LOVE gender-neutral M gender-neutral t F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual bois bois M gender-neutral M gender-neutral t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident -

LGBT/Two Spirit Definitions Lesbian Is a Woman Whose Enduring Physical, Romantic, Emotional And/Or Spiritual Attraction Is to Other Women

12/12/2012 Mending the Rainbow: Working with the Native LGBT/Two Spirit Community Presented By: Elton Naswood, CBA Specialist National Native American AIDS Prevention Center Mattee Jim, Supervisor HIV Prevention Programs First Nations Community HealthSource LGBT/Two Spirit Definitions Lesbian is a woman whose enduring physical, romantic, emotional and/or spiritual attraction is to other women. Gay is a man whose enduring physical, romantic, emotional and/or spiritual attraction is to other men Bisexual is an individual who is physically, romantically, emotionally and/or spiritually attracted to men and women. Transgender is a term for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs form the sex they were assigned at birth. Two Spirit is a contemporary term used to identify Native American Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and some Transgender individuals with traditional and cultural understandings of gender roles and identity. 13th National Indian Nations Conference ~ Dec 2012 1 12/12/2012 Two Spirit – Native GLBT Two Spirit term refers to Native American/Alaskan Native Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender (LGBT) individuals A contemporary term used to identify Native American Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender individuals with traditional and cultural understandings of gender roles and identity. Encompassing term used is “Two Spirit” adopted in 1990 at the 3rd International Native Gay & Lesbian Gathering in Winnipeg, Canada. Term is from the Anishinabe language meaning to have both female and male spirits within one person. Has a different meaning in different communities. The term is used in rural and urban communities to describe the re- claiming of their traditional identity and roles. The term refer to culturally prescribed spiritual and social roles; however, the term is not applicable to all tribes Two Spirit – Native LGBT . -

LGBT Handbook

A Provider’s Handbook on CulturallyCulturally CompetentCompetent CareCare LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER POPULATION 2ND EDITION Kaiser Permanente National Diversity Council and Kaiser Permanente National Diversity A PROVIDER’S HANDBOOK ON CULTURALLY COMPETENT CARE LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER POPULATION 2ND EDITION Kaiser Permanente National Diversity Council and Kaiser Permanente National Diversity TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................6 DEMOGRAPHICS .......................................................................................................7 Definitions & Terminology..................................................................................7 LGBT Relationships..............................................................................................9 LGBT Families......................................................................................................9 Education, Income and Occupation.................................................................10 Health Care Coverage........................................................................................10 Research Constraints..........................................................................................11 Methodological Constraints ...............................................................................11 Implications for Kaiser Permanente Care Providers........................................11 HEALTH BELIEFS AND BEHAVIORS......................................................................12 -

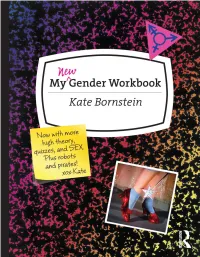

MY New Gender Workbook This Page Intentionally Left Blank N E W My Gender Workbook

my name is ________________________ and this is MY new gender workbook This page intentionally left blank N e w My Gender Workbook A Step-by-Step Guide to Achieving World Peace Through Gender Anarchy and Sex Positivity Kate Bornstein Routledge Taylor & Francis Group NEW YORK AND LONDON Second edition published 2013 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2013 Taylor & Francis The right of Kate Bornstein to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. First edition published by Routledge 1998 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Bornstein, Kate, 1948– My new gender workbook: a step-by-step guide to achieving world peace through gender anarchy and sex positivity/ Kate Bornstein.—2nd ed. p. cm. Rev. ed. of: My gender workbook. 1998. 1. Gender identity. 2. Sex (Psychology) I. Bornstein, Kate, 1948– My gender workbook. II. -

Seeing Gender Classroom Guide

CLASSROOM GUIDE Seeing Gender An Illustrated Guide to Identity and Expression Written and Illustrated by Iris Gottlieb Foreword by Meredith Talusan 978-1-4521-7661-1 • $39.95 HC 8.3 in x 10.3 in, 208 pages About Seeing Gender: Seeing Gender is an of-the-moment investigation into how we express and understand the complexities of gender today. Illustrating a different concept on each spread, queer author and artist Iris Gottlieb touches on history, science, sociology, and her own experience. It’s an essential tool for understanding and contributing to a necessary cultural conversation about gender and sexuality in the 21st century. In the classroom, Seeing Gender can be used as: • An entry point to understanding the vast complexities and histories of gender expression. • A self-education tool that will allow for nonjudgmental exploration of your own gender, increased empathy and understanding of others’ experiences, and an invitation to consider the intricacies of intersectionality. • A look into how coexisting identities (race, class, gender, sexuality, mental health) relate to gender within larger social systems. This guide contains extensive excerpts along with thought-provoking questions, quizzes, and writing prompts. To learn more about Seeing Gender, visit chroniclebooks.com/seeinggender. SEEING GENDER CLASSROOM GUIDE Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................... 3 Discussion Questions ........................................................ 34 Terminology ......................................................................... -

SEXUALITIES and GENDERS in ZAPOTEC OAXACA Sexualities and Genders in Zapotec Oaxaca

LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES Stephen / SEXUALITIES AND GENDERS IN ZAPOTEC OAXACA Sexualities and Genders in Zapotec Oaxaca by Lynn Stephen The southern Mexican state of Oaxaca provides a cross-section of the multiple gender relations and sexual behaviors and roles that coexist in mod- ern Mexico.Looking at contemporary gender and sexuality in two Zapotec towns highlights the importance of historical continuities and discontinuities in systems of gender and their relationship to class, ethnicity (earlier coded as race), and sexuality.The various sexual roles, relationships, and identities that characterize contemporary rural Oaxaca suggest that instead of trying to look historically for the roots of “homosexuality,” “heterosexuality,” or even the concept of “sexuality,” we should look at how different indigenous sys- tems of gender interacted with shifting discourses of Spanish colonialism, nationalism, and popular culture to redefine gendered spaces and the sexual behavior within them.Clear differences between elites and those on the mar- gins of Mexican society underscore the importance of divisions by class and status. I begin by presenting ethnographic snapshots of gender and sexuality in two different sites in contemporary Oaxaca that will provide a sense of the uniqueness of each place and the great variety found within this relatively small geographic area.Some of the key elements that emerge from these snapshots are a third gender role for biologically sexed men in Zapotec com- munities, the muted presence of a gender hierarchy in which women’s sexual activity is controlled before and during marriage, an alternative discourse among Zapotec migrants that grants both men and women some independent control over their sexuality within the bounds of serial monogamy, and the emergence of sexual identities apart from gender, including “gay,” “homo- sexual,” “joto,” and “maricón” as imports from elsewhere in Mexico and the United States.The remainder of the analysis attempts to link these contempo - rary elements of gender and sexuality to their historical roots. -

From Third Gender to Transgender Indicate If Seminar And/Or Writing II Course Seminar

General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Anthropology 98T Course Title The Anthropology of Gender Variance Across Cultures: From Third Gender to Transgender Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course Seminar 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities · Literary and Cultural Analysis · Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis · Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture · Historical Analysis · Social Analysis x Foundations of Scientific Inquiry · Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) · Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This seminar builds on Foundations of Society and Culture as anthropology constitutes one of the social sciences. The seminar incorporates concepts, theories, and research pertaining to gender as a major organizing principle in all known societies. Since the class materials span many decades of research, historical foundations and their critical analysis of this particular field of inquiry are essential in understanding its development and scholarly evolution. Social analysis of cultural contexts builds dynamically on historical foundations including social theory, literary criticism, and socio-political implications. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Muriel Vernon, PhD Candidate (instructor), Douglas Hollan, PhD (faculty sponsor). Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes No X If yes, please indicate the number of TAs 3. -

Working with the Nagve LGBT/Two-Spirit Community

Mending the Rainbow: Working with the Na4ve LGBT/Two-Spirit Community Presented By: Elton Naswood (Navajo) Independent Consultant Learning Objectives § Explain the GBLQ, Two Spirit, & Transgender Identities. § Explain how Native culture interacts with GLBTQ2S Identities. § Discuss intimate partner violence and myths. § Discuss barriers and challenges for GLBTQ2S victims. § Identify strategies and resources to assist GLBTQ2S individuals. Lesbian, Gay, Bi-Sexual, Queer, & Two-Spirit Definitions § Lesbian: Woman whose enduring physical, romantic, emotional and/or spiritual attraction is to other women. § Gay: Man whose enduring physical, romantic, emotional and/or spiritual attraction is to other men § Bisexual: An individual who is physically, romantically, emotionally and/or spiritually attracted to men and women. Lesbian, Gay, Bi-Sexual, Queer, & Two-Spirit Definitions § Queer: An inclusive term which refers collectively to lesbians, gay men, bisexual and transgender folKs and others who may not identify with any of these categories but do identify with this term. While once used as a hurtful, oppressive term, many people have reclaimed it as an expression of power and pride § Two Spirit: A contemporary term used to identify Native American Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and some Transgender individuals with traditional and cultural understandings of gender roles and identity. Two Spirit Defini4on § Two Spirit term refers to Native American/Alaska Native Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual individuals. § A contemporary term used to identify Native American Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender individuals with traditional and cultural understandings of gender roles and identity. § Encompassing term used is “Two Spirit” adopted in 1990 at the 3rd International Native Gay & Lesbian Gathering in Winnipeg, Canada. Two Spirit Definition § Term is from the Anishinabe language meaning to have both female and male spirits within one person. -

Working with Native LBGT/Two Spirit Community

1/24/2011 Mending the Rainbow: Working with Native LBGT/Two Spirit Community Presented By: Elton Naswood, Project Coordinator Red Circle Project, AIDS Project Los Angeles Mattee Jim, Prevention/Support Services Coordinator First Nations Community HealthSource 12th National Indian Nations Conference December 9, 2010 ~ Palm Springs, CA Two Spirit – Definition Two Spirit term refers to Native American/Alaska Native Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender (LGBT) individuals Came from the Anishinabe language. It means having both female and male spirits within one person. Has a different meaning in different communities. 1 1/24/2011 History of Two Spirits Encompassing term used is “Two Spirit” adopted in 1990 at the 3rd International Native Gay & Lesbian Gathering in Winnipeg, Canada. The term is used in rural and urban communities to describe the re-claiming of their traditional identity and roles. The term refer to culturally prescribed spiritual and social roles; however, the term is not applicable to all tribes. Tribal Language and Two Spirit Terminology Tribe Term Gender Crow boté male Navajo nádleehí male and female Lakota winkte male Zuni lhamana male Omaha mexoga male 2 1/24/2011 Spirituality and Culture “Alternative gender roles were respected and honored and believed to part of the sacred web of life and society.” Lakota view: Wintkes are sacred people whose androgynous nature is an inborn character trait or the result of a vision. Example: Lakota Naming Ceremony For many tribes, myths revealed that two-spirit were decreed to exist by deities or were among the panethon of gods.” . Example: Navajo Creation Story – The Separation of Sexes Two Spirit/LGBT Umbrella Lesbian Transgender Gay Bisexual Two Spirit A woman whose enduring A term for people whose physical, romantic, emotional gender identity and/or and/or spiritual attraction is to gender expression differs An individual who is other women. -

Two Spirit, Transgender, Latino/A, African American Pacific Islander, and Bisexual Communities

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. INCLUSIVE STORIES Although scholars of LGBTQ history have generally been inclusive of women, the working classes, and gender-nonconforming people, the narrative that is found in mainstream media and that many people think of when they think of LGBTQ history is overwhelmingly white, middle-class, male, and has been focused on urban communities. While these are important histories, they do not present a full picture of LGBTQ history. To include other communities, we asked the authors to look beyond the more well-known stories. Inclusion within each chapter, however, isn’t enough to describe the geographic, economic, legal, and other cultural factors that shaped these diverse histories. Therefore, we commissioned chapters providing broad historical contexts for two spirit, transgender, Latino/a, African American Pacific Islander, and bisexual communities. -

Gero 705.02 Transgender.Pub

Two Spirited Elders A Resource Fact Sheet for Aging Transgendered People In the San Francisco Bay Area By Laura C. Strom, [email protected], Created for Gerontology 705, Aging in a Multidimensional Context, Dr. Brian de Vries, December 2005. SOME BASIC DEFINITIONS A transgender symbol, a Two Spirit is an over arching term adopted in 1990 combination of the male and female sign with a by Native people to cover people who might be third, combined arm rep- termed gay, lesbian, dyke, femme, transgender, resenting transgender transvestite, transsexual, inter-sexed, hermaphro- people. dite, and queer among other terms. Many tribes Image retrieved December 1, have terms for a third and fourth gender, besides 2005 from http:// male and female. Some tribes held Two-Spirited en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ people in high regard, while others did not. What is Transgender important to know is that Two-Spirited people were acknowledged and a part of nearly every tribe. Terms for Two-Spirit exist in over 155 tribes. Two Spirit is a term which honors the experience of and is preferred by Image retrieved October 31, 2005 many transgendered people. from http://imagyst.com/fine-first- According to Wikipedia the definition for transgendered person remains in twospirits.html flux, but the most accepted one currently is: PREVELENCE People who were assigned a gender, usually at birth and based on their It is very difficult to accu- genitals, but who feel that this is a false or incomplete description of rately estimate the preva- themselves. lence of transgendered indi- A transsexual person is a person who has gone through the process of sex- viduals. -

First, Do No Harm: Reducing Disparities for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Questioning Populations in California

First, Do No Harm: Reducing Disparities for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Questioning Populations in California The California LGBTQ Reducing Mental Health Disparities Population Report First, Do No Harm: Reducing Disparities for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Questioning Populations in California The California LGBTQ Reducing Mental Health Disparities Population Report Table of Contents Acknowledgements .. 4 Executive Summary .. 11 Part 1: Introduction and Background Information . 18 What We Know, What We Don’t Know and What We Need to Know About LGBTQ . 20 Research Issues: Who Counts, What Counts, How to Count . 20 History - The Sexologists . ...................22 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . .............25 Gender Identity Disorder (GID) . ...............27 Etiology: The “Choice” Debate . ....................32 The Many Forms of Stigma . ................35 Minority Stress . .......................37 Majority Rules - Anti-LGBTQ Initiatives .. ..................39 Coming Out / Staying In . .................44 HIV and AIDS .. ......................45 Alcohol and Other Drugs (AOD) . ..............46 Domestic Violence .................................... ........................47 Suicide ............................................ ..........................52 Resiliency ......................................... ..........................52 Mental Health Services: The Good, the Bad, and the Harmful . .............54 First Do No Harm . ......................56 Lack of Training